Hair and Nail Abnormalities

Jennifer E. Yeh

Jennifer T. Huang

HAIR CHANGES

Hair loss is one of the most common and distressing side effects of cancer treatment and can be seen with cytotoxic and targeted chemotherapies as well as immunotherapy. Given the effect on personal appearance, generalized alopecia often impacts patients’ perspectives on self-image as well as their emotional well-being, frequently viewed as losing a sense of privacy.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy typically induces anagen effluvium, with generalized thinning of the scalp and body hair. Shedding usually begins within 14 days of introduction of the offending agent (antimetabolites, alkylating agents, and mitotic inhibitors most commonly). Though historically accepted as an unavoidable dermatologic adverse event with chemotherapy, scalp cooling has been shown to be safe and effective at reducing rates of chemotherapy-induced alopecia (CIA); cooling reduces the need for a wig across multiple different chemotherapy regimens and solid malignancies, with greatest success in the setting of taxane monotherapy.1,2 It has also been shown to increase the rate of hair recovery and protect against permanent CIA.3 In addition to prevention with cooling, other interventions include topical minoxidil 2% to 5% twice daily throughout treatment, which can delay time to maximal loss and reduce time to regrowth.4,5 Although hair typically grows back after discontinuation of therapy, the texture and density are often affected, and rarely, CIA can be permanent (Figure 18.1).

Figure 18.1. Persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia, with diffuse thinning, most evident over the vertex. |

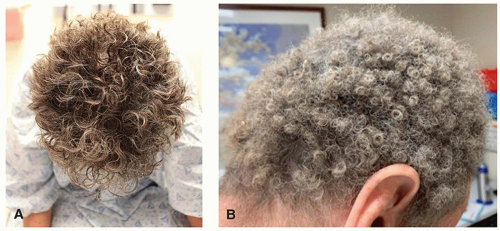

Targeted therapies, particularly MAPK pathway inhibitors such as BRAF and MEK inhibitors4,6 as well as EGFR, BTK, and BCR-Abl/KIT inhibitors, may induce hair changes; other targeted therapies may also be implicated to varying degrees. Changes may include increased brittleness, straight hair becoming curly (Figure 18.2), and less commonly, curly hair becoming straight. Pigmentary dilution of hair, or hair graying, has been reported with multikinase inhibitors (sorafenib, sunitinib, imatinib, cabozantinib, pazopanib) (Figure 18.3), presumably due to inhibition of c-KIT which plays a critical role in melanocyte proliferation.7,8,9 Patients receiving cyclical kinase inhibitors can develop alternating horizontal bands of depigmented and normal hair giving a striped appearance.9 While biotin supplementation can improve hair brittleness, it is important to note that this supplement can interfere with immunoassays, leading to incorrect results of certain laboratory tests. Among others, these include falsely elevated thyroid function and falsely low troponin tests. Patients should be counseled on this to properly inform other health care professionals of their supplements.

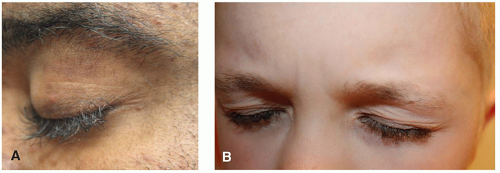

Eyelash trichomegaly (Figure 18.4) is well described in association with EGFR inhibitors.10,11 Although the mechanism is largely unknown, some hypothesize that systemic inhibition of EGFR affects hair follicle progression leading to an aberrant anagen phase and abnormal hair growth. Eyelash trichomegaly can obscure vision and has been reported to cause corneal erosions, irritation, and in some cases infection. Therefore,

trimming of elongated eyelashes is recommended for patients experiencing eyelash trichomegaly.

trimming of elongated eyelashes is recommended for patients experiencing eyelash trichomegaly.

Figure 18.2. Curly, short, brittle hair in the setting of EGFR (A) and kit (B) inhibitor targeted therapy. |

Figure 18.4. Eyelash trichomegaly in an adult an EGFR inhibitor (A) and a child on a MEK inhibitor (B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|