The most common presenting complaint in carcinoma of the vulva is itching.

Vaginal Candidiasis is less common in post menopausal women than in younger women.

The most common benign affliction of the female genitalia is contact dermatitis.

The incidence of breast cancer increases with age. Most women in whom breast cancer is diagnosed have no identifiable risk factors.

Any vaginal bleeding in an elderly woman requires a diagnosis. Malignancy must be considered because of its life-threatening consequences.

embarrassment, fear that they may be unclean or smell, that the examination will be painful, that some pathology may be found, and physical limitations to positioning themselves on the table.

a Pap smear in the last 5 years, a woman who has not had Pap smears is a candidate for the procedure. Although women whose life expectancy is <5 years are unlikely to benefit from screening Pap smears, a recent study reported high rates of this screening procedure in women older than 75 (79%), and even in those older than 80 (72%).2 The authors point out that the median life expectancy for women in the United States exceeds 5 years until age 90.

relieve some of the discomfort. Pelvic floor exercises have been helpful to some women. Referral to a pain clinic may be indicated.

TABLE 32.1 SOME CAUSES OF VULVAR OR VAGINAL PRURITIS IN POSTMENOPAUSAL WOMEN | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

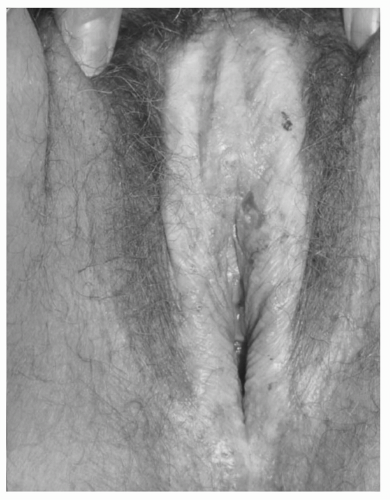

yearly. Treatment is recommended for all patients, even if asymptomatic, to prevent the progression of the disease. Untreated, it can lead to shrinkage of the vulvar skin and introital stenosis. Superpotent topical corticosteroids, such as clobetasol7 (Evidence Level A, randomized controlled trial) or halobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment daily for 6 to 12 weeks and then one to three times per week for maintenance, have been shown to be efficacious. Steroid ointments are preferred over creams because creams may contain irritants not found in ointments. For severe lesions, intralesionsal injections of triamcinolone seem to be effective8 (Evidence Level B).

sexual partner should be treated. Topical treatments are ineffective. Tinidazole is an alternative treatment for resistant Trichomonas,11 which is also given orally in a single 2-g dose. Both drugs interact with alcohol, so the patient should be cautioned to avoid any alcohol-containing products while taking the medication, and for 72 hours afterward in the case of tinidazole, which has a longer half-life.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree