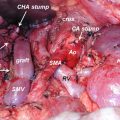

Fig. 12.1

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram showing multiple branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs)

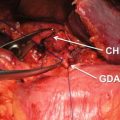

Fig. 12.2

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram demonstrating a mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN)

12.2 Guidelines for the Management of PCNs

To date, at least eight guidelines or statements for the management of PCNs, or more specifically IPMN and MCN, have been published in the English literature. Since no significant data exist from prospective studies yet, all the guidelines and statements are based on a critical review of available data and consensus of experts.

12.2.1 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Guideline

To the best of our knowledge, the guideline on the role of endoscopy in the management of cystic lesions of the pancreas published by the ASGE in 2005 might be the first [7]. This ASGE guideline described the roles of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) with/without EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) with cyst content cytology, chemistry, and tumor marker analysis for differentiation of mucinous from non-mucinous PCNs and for diagnosis of malignancy. The CEA cutoff level of 192 ng/ml provided a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 84% for differentiating mucinous tumors from other cystic lesions. CEA is invariably below 5 ng/ml in SCNs, while the level was usually, but not always (<5 ng/ml in 7%), high in mucinous cysts. Malignancy within a PCN could be identified by cytology with 83–100% specificity, although sensitivity greatly varied from 25% to 88%. Among a variety of roles of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), duodenoscopy might disclose the highly specific finding of patulous orifice of the papilla filled with mucin in IPMN patients. The rest of the guideline dealt with EUS morphology, cytology, chemistries, and tumor markers of the cyst content obtained by EUS-FNA, other kinds of PCNs, and the roles of endoscopy in the management of pancreatic fluid collection.

12.2.2 American College of Gastroenterology Guideline

In 2007, American College of Gastroenterology proposed a guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of PCNs with their suggestions on 13 common clinical problems [8]. This guideline dealt with a variety of PCNs and nonneoplastic pancreatic cysts. Regarding IPMN, it described that the risk of malignancy increases with older age, the presence of symptoms, involvement of the main pancreatic duct (MPD), dilation of the MPD over 10 mm, the presence of mural nodules, and size over 3 cm for BD-IPMN. It also referred to cytological analysis, determination of tumor marker concentrations, and molecular diagnostic evaluations from samples obtained by EUS-FNA. It mentioned identification of papillary projections associated with malignant transformation and determination of the longitudinal extent of IPMN by pancreatoscopy as well. The risk of malignancy of MCN was claimed to be less than that associated with MD-IPMN and suggested by greater size (>2 cm), cyst wall irregularity and thickening, intracystic solid regions, an adjacent solid mass, and perhaps calcification of the cyst wall. It also referred to EUS-FNA but the sensitivity of cytology was suboptimal (<50%). Resection was recommended for patients with MCN considered to be at acceptable risk for perioperative complications as was the recommendation in MD-IPMN.

12.2.3 Korean Guideline

A Korean group reported their guideline focusing on the treatment of BD-IPMN in 2008 [9]. Granting that many factors must be considered when choosing between the surgical and observation options, such as operative risk based on general condition, estimated remaining life span, the risk of malignant transformation, and the extent of surgery, they claimed that the cutoff of the cyst size of BD-IPMN for malignancy prediction should be lowered to 2 cm based on their observation of a sharp increase in malignancy potential from 2 cm, regardless of the presence of mural nodules. They stated that observation could only be recommended for BD-IPMN ≤2 cm without mural nodule. They also observed 9 “combined” pancreatic cancers (6.5%) among 31 previous or concurrent malignancies in 29 (21.0%) of 138 patients with BD-IPMN.

12.2.4 American College of Radiology White Paper

The American College of Radiology issued a white paper regarding the management of incidental CT findings including PCNs in 2010 [10].

The Incidental Findings Committee recommended the following for managing incidental pancreatic cysts:

- 1.

Surgery should be considered for patients with cysts ≥3 cm.

- (a)

If the lesion is an SCN, surgery is deferred until the cyst is ≥4 cm.

- (b)

SPN should be resected.

- (c)

Patient factors ultimately determine the appropriateness of surgical treatment.

- (a)

- 2.

Patients with simple (not containing any solid elements) cysts ≤3 cm can be followed.

- (a)

Attempts should be made to characterize all cysts ≥2 cm at the time of detection. Magnetic resonance imaging is the imaging procedure of choice.

- (b)

Cyst aspiration is strongly advised before any surgery is undertaken in a patient with a cyst of this size.

- (c)

Cysts ≤2 cm can be followed less frequently than those between 2 and 3 cm.

- (d)

Avoid characterizing cysts ≤1.5–2 cm unless absolutely characteristic.

- (a)

- 3.

The presence of symptoms is a critical factor in deciding appropriate therapy.

- (a)

The frequency of malignancy in small cysts is significantly higher in symptomatic patients.

- (a)

12.2.5 European Consensus Statements

Consensus statements on the PCNs were reported from the European study group on cystic tumors of the pancreas in 2013 [11]. A total of 26 questions concerning the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of IPMN, MCN, SCN, and SPN but no other PCNs were presented along with recommendations with grade classification where appropriate. As readily expected, there were no grade A recommendations. Resection should be considered in all symptomatic lesions, MCN, MD-IPMN, and SPN as well as in BD-IPMN with mural nodules and dilation of the MPD>6 mm considered as the most important risks for malignancy.

The statements were unique in four points. First, they admitted resection of cystic lesions without any risk factors in high-volume centers due to a cumulative risk of cancer in patients with long life expectancy or with an increased risk for cancer development. Also, a large SCN (>6 cm) and location in the head of the pancreas were considered independent risk factors for aggressive behavior that might justify surgical resection. Second, the attitude toward EUS-FNA for BD-IPMN was modest. They stated that EUS-FNA with cyst fluid analysis might be used, but there was no evidence to suggest this as a routine diagnostic method. Third, they recognized that there was no safe lower limit in size of BD-IPMN that could completely exclude malignancy. Fourth, they mentioned the limit of surveillance for BD-IPMN. If no changes occur during the first year of a 6-monthly follow-up, a yearly follow-up is then recommended for the following 5 years, and even if the patient remains asymptomatic and the IPMN unchanged, surveillance should be continued as long as the patient is fit for surgery. In other words, surveillance should be stopped when the patient has become unfit for surgery.

12.2.6 Italian Consensus Guidelines

Italian experts also issued their consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and follow-up of PCNs in 2014 [12]. With the characteristics of the Italian Healthcare System taken into consideration; this consensus was reached for each statement according to the Delphi procedure. Both the level of evidence and the grade of recommendation were reported according to the Oxford criteria. This consensus is unique in that they stressed at the beginning that no additional examinations are required when the patient is found to be unfit for any treatment and remains asymptomatic. Based on this assumption, they reported recommendations regarding the most appropriate use and timing of various imaging techniques, the role of circulating and cyst fluid markers, and the pathologic evaluation for the diagnosis and surveillance of IPMN, MCN, SCN, and SPN.

Of note is a comment that a significantly higher incidence of complications for EUS-FNA of PCNs than for solid lesions (14% vs. 0.5%, P < 0.001) has been reported, including hemorrhage, pancreatic fistula, acute pancreatitis, pancreatic abscess, and infection. Nonetheless, there is a statement that a cytological examination is useful in the differential diagnosis between benign and malignant PCNs (evidence level 2a, recommendation grade B, agreement 100%), although the adequacy and accuracy strongly depend on the overall institutional experience.

12.2.7 American Gastroenterology Association Guidelines

Most recently, two groups of the American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) performed an extensive literature review [13] and issued their guidelines on the management of asymptomatic PCNs employing the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework [14]. Just as expected, since all the evidences are graded as of very low quality, all the recommendations are conditional except for the recommendation of surgical expertise, i.e., if surgery is considered for a PCN, patients should be referred to a center with demonstrated expertise in pancreatic surgery (strong recommendation, very low quality evidence).

12.2.8 International Consensus Guidelines

The International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) issued consensus guidelines for the management of IPMN and MCN in 2006 [15], and these guidelines were updated in 2012 [16]. Sendai consensus for prediction of malignancy and the clinical management of IPMN proposed in the initial IAP guidelines was widely employed. MD-IPMN with dilation of the MPD >10 mm was a surgical indication as frequently malignant. The criteria for resection of BD-IPMN comprised of clinical symptoms (pain, pancreatitis), positive cytology, the presence of mural nodules, MPD dilation >6 mm, and cyst size >3 cm (“Sendai criteria”). Although the cyst size >3 cm was not proposed as an absolute indication for resection in the Sendai consensus, many patients were recommended surgery employing this criterion. However, the rate of malignancy in surgical specimens of this group of patients was only 13–23% [17, 18].

Then, the international consensus guidelines revised in 2012 (Fukuoka consensus) proposed two-layer criteria for prediction of malignancy in IPMN, i.e., “high-risk stigmata” to recommend immediate resection for fit patients and “worrisome features” to warrant complete examinations by EUS (Fig. 12.3) [16]. Fukuoka consensus is accepted well with higher sensitivity to diagnose main duct (MD)-IPMN and to predict malignancy in IPMN [19–21], while the adequacy of the cyst size moved from the “high-risk stigmata” to “worrisome features” is still controversial [21–24]. One meta-analysis reported that the cyst size >3 cm was associated most strongly with malignant IPMN [24], while another meta-analysis declaimed that the presence of mural nodules should be regarded most highly suspicious of malignancy [21].

Fig. 12.3

Management algorithm with two-layer criteria for stratifying risk factors to predict malignant changes of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (BD-IPMN) (Cited and reproduced with permission from Pancreatology 2012;12:183–197 with minor correction). (a) Pancreatitis may be an indication for surgery for relief of symptoms. (b) Differential diagnosis includes mucin which can move with change in patient position, may be dislodged on cyst lavage, and does not have Doppler flow. Features of true tumor nodule include lack of mobility, the presence of Doppler flow, and FNA of nodule showing tumor tissue. (c) The presence of any one of thickened walls, intraductal mucin, or mural nodules is suggestive of main duct involvement. In their absence, main duct involvement is inconclusive. (d) Studies from Japan suggest that on follow-up of subjects with suspected BD-IPMN, there is increased incidence of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma distinct from malignant transformation of the monitored BD-IPMN(s). However, it is unclear if imaging surveillance can detect ductal adenocarcinoma in its early phase and, if so, at what interval surveillance imaging should be performed

In this regard, there exist many reports of invasive carcinoma found in BD-IPMNs ≤3 cm without mural nodules (“flat” BD-IPMN) [23, 25]. This is contradictory to the white paper issued by the American College of Radiology that recommends avoidance of characterizing asymptomatic small cysts <2 cm. The relationship between the risk of malignancy and cyst size should be evaluated without the influence of mural nodules or MPD dilation.

Sadakari et al. [17] reported the frequency of malignancy of 3.6% in BD-IPMNs ≥30 mm without mural nodules or MPD dilation (<5 mm), while it was 26.3% when the MPD diameter was ≥5 mm or more. Fritz et al. [22] reported that 17 of 69 patients (24.6%) with BD-IPMNs <3 cm showed malignancy (invasive carcinoma or HGD), but EUS was not performed in all the patients. Wong et al. [23] reported 105 patients with BD-IPMN without Sendai criteria on EUS. Twenty-four (34%) of 70 cysts ≤3 cm were invasive cancer, including 1 of 7 cysts <1 cm (14%), 2 of 19 cysts 1–2 cm (11%), and 21of 44 cysts 2–3 cm (48%). On the other hand, 15 of 35 cysts (43%) >3 cm were invasive cancer. Sixteen cysts ≤3 cm (23%) had HGD, including 3 of 7 cysts <1 cm (43%), 3 of 19 cysts 1–2 cm (16%), and 10 of 44 cysts 2–3 cm (23%). Shimizu et al. [26] also reported that 9.4% of 160 patients with malignant IPMN (noninvasive 100, invasive 60) had no mural nodules on EUS. Furthermore, Koshita et al. [27] reported that 9 (43%) of 21 patients with invasive IPMN had no mural nodules on EUS.

Although the reliability of EUS examination is quite observer dependent, we have to realize that the absence of mural nodules does not absolutely guarantee the safety of IPMN. The patient’s age, location of the cyst, medical conditions, and operative risks must also be considered. Younger ages of the patient should be taken into account as well in view of the cumulative risk of cancer development during his/her lifetime [28].

12.3 Lengthening of Surveillance Interval

Adequate methodologies and intervals of surveillance of BD-IPMN to check the malignant changes and/or the development of concomitant but distinct PDAC remain to be determined. Fukuoka consensus recommended yearly follow-up for cysts <10 mm, 6–12 monthly follow-up for cysts 10–20 mm, and 3–6 monthly follow-up for cysts >20 mm [16]. Fukuoka consensus advocated lengthening of the surveillance interval after 2 years of no change on images, whereas it suggested not to lengthen the intervals >6 months in view of the relatively high incidence of concomitant PDAC mentioned above. A French group claimed the adequacy of lengthening of the surveillance intervals in view of a low incidence of the malignant change in IPMN, yet they recommended biannual imaging studies [29]. Tamura et al. [30] showed that even a 6-month interval might be insufficient for the timely diagnosis of a concomitant PDAC in a patient with IPMN.

12.4 When to Stop Surveillance

Whether we can stop surveillance of patients with BD-IPMNs or not, and, if yes, when to stop remain debatable. It is surely useless to continue surveillance of those who cannot be candidates for surgery. However, the chronological age per se, 85 years old, for example, should not be taken as the limit for surveillance, because the medical condition of each patient is different.

The American College of Radiology recommended stopping the surveillance after 2 years when a small cyst shows no change [10]. Fukuoka consensus stated that there were no good long-term data to indicate whether surveillance can be safely spaced to every 2 years or even discontinued after long-term stability [16]. Recently, the AGA guidelines have recommended quitting surveillance when a cyst does not show a significant change in 5 years, if high-risk features are completely negated and the patient does not have a strong family history of PDAC [14]. They state that the small risk of malignant progression in stable cysts is likely outweighed by the costs of surveillance.

However, these recommendations to stop surveillance of BD-IPMNs are now questioned as there are no long-term data to support this concept, and moreover, there are so many reports of retrospective studies addressing the long-lasting risk of development of concomitant pancreatic cancer in patients with IPMNs and a history of IPMNs [30–60]. Khannoussi et al. [46] found two PDACs concomitant with IPMN both after 84-month follow-up and concluded that imaging surveillance was still necessary beyond 5 years. Likewise, Lafemina et al. [49] also noted that 5 of the 18 patients with invasive carcinoma found in 97 patients with BD-IPMN resected developed PDAC in a region distinct from monitored IPMN (5.2%) and stressed the importance of consideration of risk not only to the index cyst but also to the entire gland in surveillance strategy of IPMN. The significance of indefinite surveillance was repeatedly noted as early as in the 2000s as well [61, 62]. He et al. [50] also emphasized that patients who have undergone resection for noninvasive IPMN require indefinite close surveillance because of the risks of developing a new IPMN, of requiring surgery, and of developing cancer (0%, 7%, and 38% at 1, 5, and 10 years, respectively). More recently, Miyasaka et al. [58] also stated that the incidences of both malignant IPMN and concomitant cancer rise further even after 5 years.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree