Familial short stature

Children with familial (genetic) short stature have short parent(s) with a history of normal puberty. These children have normal growth velocity, timing of puberty and bone age.

Constitutional delay of growth and puberty

Constitutional delay of growth and puberty (CDGP) is the one of the most common conditions presenting to paediatric endocrinologists. It is a normal variant of growth and puberty, and is characterized by a delayed onset of puberty, the pubertal growth spurt and skeletal maturation (i.e. delayed bone age).

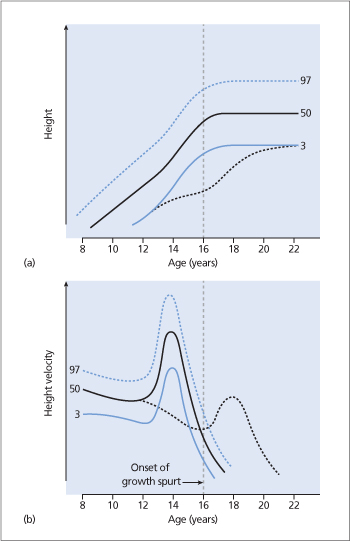

The growth chart and growth velocity of a boy with CDGP is shown in Fig. 30.1. In the years preceding the expected time of puberty, the growth pattern of these children is normal (usually along the lower growth percentiles). The height of the child begins to drift from the growth curve because the onset of pubertal growth spurt is delayed. However, the child’s height is appropriate for his bone age. Physical examination and biochemical investigations are normal and prepubertal. Patients often have a family history of late onset of puberty in one or both parents. The predicted height for the child is in the appropriate range for the parental heights.

Endocrine abnormalities

Children with abnormalities in the endocrine control of growth have reduced growth velocity and are usually overweight for height.

GH deficiency

GH deficiency is the most common endocrine cause of short stature. GH deficiency may be isolated or associated with other pituitary hormone deficiencies (see Chapters 12 and 13).

GH secretion is stimulated by hypothalamic GH-releasing hormone (GHRH). GH stimulates epiphyseal prechondrocyte differentiation and linear bone growth in children. GH also stimulates skeletal growth through a stimulation of the hepatic synthesis and secretion of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which is a potent growth and differentiation factor. GH deficiency usually results from a deficiency of GHRH, but can be secondary to sellar and parasellar tumours such as germinoma.

Figure 30.1. (a) Serial height measurements of a boy with constitutional delay of growth and puberty (CDGP; dotted black line) are plotted on a growth chart with 3rd, 50th and 97th percentile lines. Note that the height of the child falls below the 3rd percentile line during the early teenage years because of the delay in onset of the pubertal growth spurt. (b) Growth velocity of a boy with CDGP (dotted black line) is plotted on a growth velocity chart with 3rd, 50th and 97th percentile lines. Note the delayed onset of the growth spurt (arrow) and reduced peak height velocity.

Rare causes of short stature include an inactivating mutation of the GHRH receptor inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, homozygous GH gene deletion, abnormalities of the GH receptor (Laron’s syndrome) and abnormal IGF-1 secretion or action.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is a well-recognized cause of short stature. The skeletal age is usually as delayed as the height age, and as a result many children with hypothyroidism have a reasonably normal growth potential.

Cushing’s syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome in children is usually iatro-genic, due to glucocorticoid therapy for asthma, inflammatory bowel disease or immunological renal disease. Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is rare but should be considered if the child has both weight gain and growth retardation. Bone age is normal at diagnosis in most patients.

Dysmorphic syndromes associated with abnormal skeletal growth

Abnormalities in skeletal growth are features of certain syndromes such as Turner’s syndrome (see Chapter 21), Down’s syndrome (trisomy 21) and achondroplasia (caused by an autosomal dominant mutation in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3, resulting in abnormal cartilage formation).

Malnutrition or chronic illness

Malnutrition or chronic illnesses such as congenital heart disease, asthma, cystic fibrosis, coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic kidney disease, vitamin D deficiency or HIV infection can result in short stature. These children are usually underweight for height.

Psychosocial problems

Psychosocial problems in childhood can contribute to short stature. These children have reduced growth velocity.

Idiopathic

Idiopathic short stature is the term applied to children with short stature in whom no endocrine, metabolic or other diagnosis can be made. These children have normal (often at the lower limit) growth velocity. Mutations in the short stature homeobox (SHOX) gene are responsible for up to 15% of cases of apparent ‘idiopathic’ short stature.

Clinical evaluation

A full medical history should be taken to determine:

- birth weight and history of any illnesses during infancy/childhood

- the parents’ height (heights reported by adults may be inaccurate and should be measured)

- the stage of puberty

- a family history of delayed puberty

- nutrition and any features of systemic illness

- psychosocial problems.

A thorough clinical examination should be performed to look for the following:

- Reduced growth velocity: accurate serial measurement of height and plotting of the measurements on a growth chart is essential to determine the growth velocity (Fig. 30.2).

- Underweight/overweight

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree