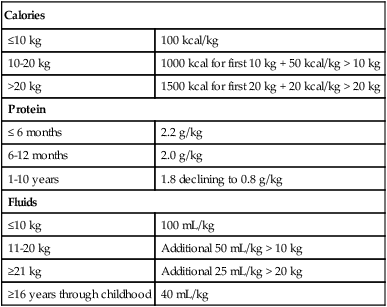

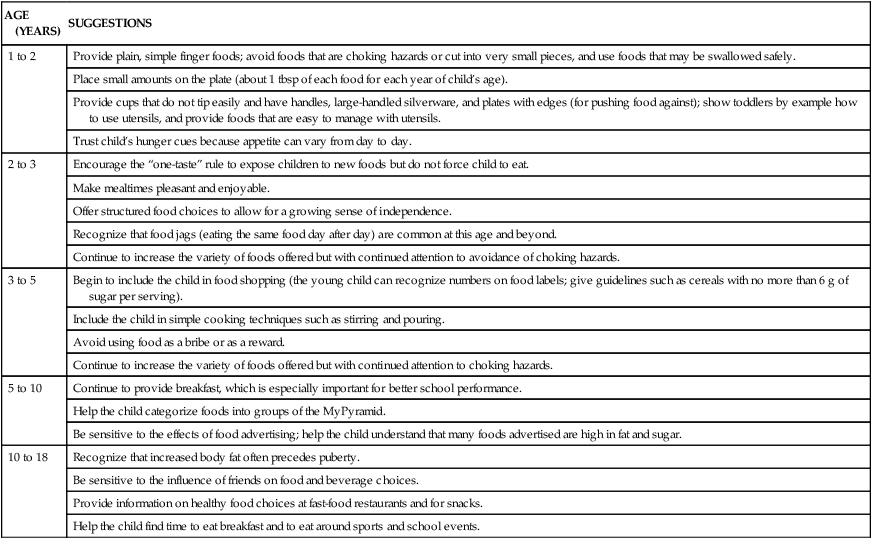

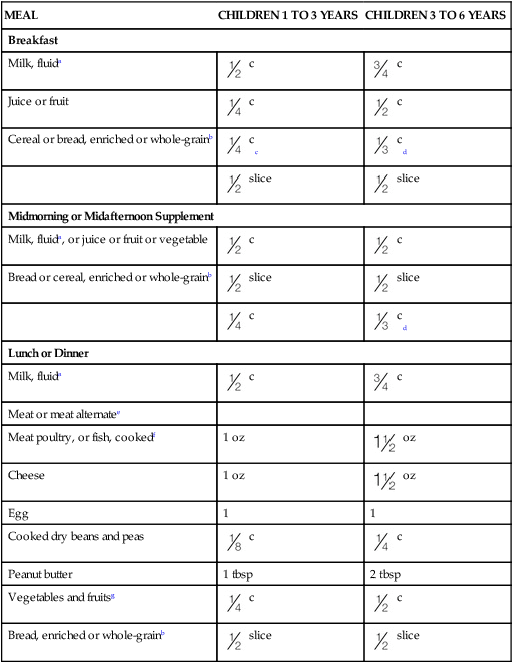

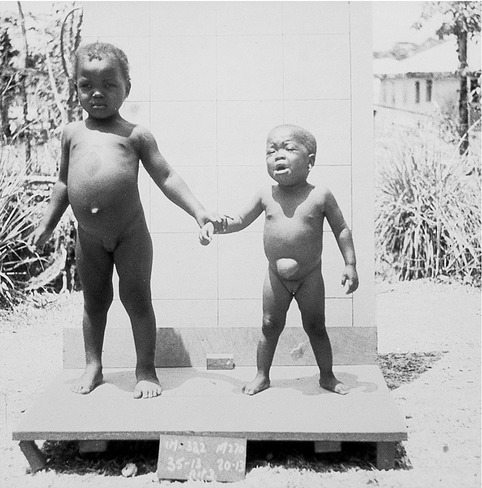

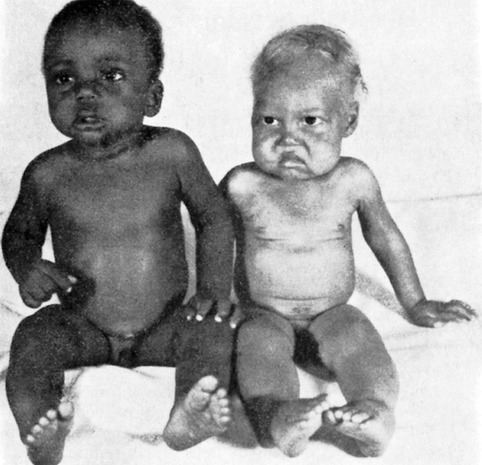

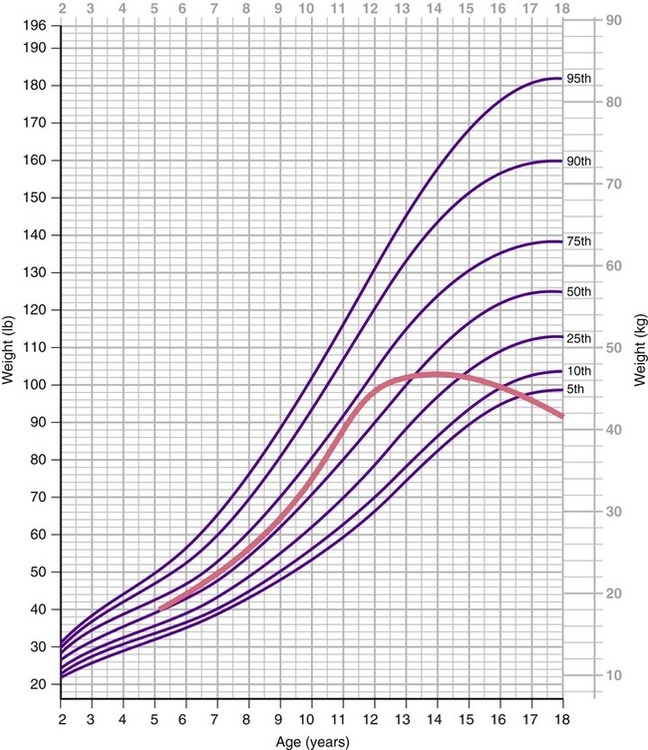

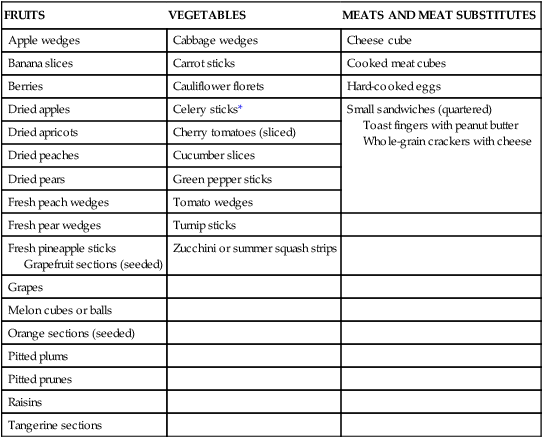

After completing this chapter, you should be able to: • Describe nutritional needs of children and adolescents. • Assess a child’s nutritional needs based on growth charts. • Describe methods to promote optimal nutritional intake. • Describe assessment and intervention strategies for common childhood health concerns. • Discuss the nutritional needs of athletic children. • Apply knowledge of the nutrient needs to the meal environment. Bone growth is the growth that occurs in length and thickness of bones. Although there is a genetically defined potential for growth, without adequate nutrients the growth process will be stunted. Chronic long-term undernutrition generally results in stunted growth (Figure 12-1). The adverse effect on growth with zinc deficiency has been known for over 40 years. Nutritional growth retardation refers to stunting of growth from lack of nutrients required to achieve genetic growth potential. Poverty is a known factor contributing to nutritional growth retardation around the world (see Figure 12-1). This results from lack of protein and kcalories (kcalories or kcal) along with inadequate intake of the various vitamins and minerals, including zinc. There may be no clinical or laboratory evidence of malnutrition other than a deceleration in growth (Cole and Lifshitz, 2008). Health care professionals should assess a child’s diet based on the MyPyramid food guide if nutritional growth retardation is suspected. Clearly calcium and vitamin D are integral to the growth of bone. Calcium can come from a variety of sources. Traditional Asian cuisine includes regular intake of small whole fish. With the intake of fish bones and fish liver, both calcium and vitamin D needs can be met. Vitamin D–fortified milk is another source. Adult height was shown to be affected by milk consumption during childhood and adolescence (Wiley, 2005). Other factors found to affect children’s bone mineral content include intakes through the younger years of protein, kcalories, vitamin K, and the minerals phosphorus and iron (Bounds and colleagues, 2005). These nutrients are found in milk, with the exception of iron. It is appropriate for a child to have flavored milk as needed to encourage intake because this will promote growth and development and not obesity in recommended quantities (Murphy and colleagues, 2008). Parents from a variety of backgrounds (Asian, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white) were found to lack expectations for their children to drink calcium-rich beverages with meals (Cluskey and colleagues, 2008). Thus the health care professional can help promote bone strength and growth by relaying to parents of young children the benefits of drinking milk and can advise flavored milk as needed. Severe malnutrition, which is characterized by clinical manifestations, is of two basic types: kwashiorkor, a protein deficiency (Figure 12-2), and marasmus, an overall deficit of food, especially kcalories (also known as protein-energy malnutrition [PEM]) (Figure 12-3). Kwashiorkor generally occurs at or after weaning, when milk high in protein is replaced by a starchy staple food that provides insufficient protein. A child with this type of malnutrition usually has stunted growth, edema, skin sores, and discoloration of dark hair to red or blond. Infantile marasmus is frequently the result of early cessation of breastfeeding, overdilution of formula, or gastrointestinal infection early in life, and it is accompanied by wasting of tissues and extreme growth retardation. Marasmus and kwashiorkor do occur in the United States but have been quite rare in recent years. However, with the current rise in food prices, including milk, and other costs such as gasoline, families with young children may be forced to cut back on nutritious foods for their children, with the potential to see increased incidence of kwashiorkor especially. Refer back to Chapter 2 for more discussion of kwashiorkor and marasmus. Nutrition is vital in the process of communication of brain cells for processing information and controlling actions. Adequate blood glucose is essential for mental performance, particularly for demanding, long-duration tasks. Malnourished children who include breakfast have increased mental performance and with increased intake of vitamins and minerals have shown improved intelligence scores. Children with poor school performance were less likely to eat foods high in protein, vitamins, and minerals while having a higher intake of sugar and fats (Fu and colleagues, 2007). In the brain the nerve endings contain one of the highest concentrations of vitamin C in the human body. Vitamin E is directly involved in nervous membrane protection and is actively taken up the brain. Vitamin K is involved in nervous tissue function. Iron is needed for oxygen-related production of energy in the brain. The B vitamins and iodine provided by the thyroid hormone ensures the energy metabolism of brain cells (Bourre, 2006). Every child has different nutrient requirements based on factors such as chronologic age, individual growth rate, stage of maturation, level of physical activity, and the efficiency of absorption and use of nutrients (Table 12-1). Guidelines such as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) and the Dietary Guidelines give general indications of needed nutrients for growth. Among adolescents low bone mineral density, as related to osteoporosis, was associated with evidence of low vitamin B12 status. This was particularly evident among adolescents who were fed a macrobiotic diet during early childhood, which contributed to low vitamin B12 levels (Dhonukshe-Rutten and colleagues, 2005). Table 12-1 Daily Macronutrient and Fluid Needs for Children Growth charts are another important tool (see Appendix 12 on the Evolve website and discussion later). If the child’s growth is appropriate, it can be generally assumed that nutritional intake is adequate. Health problems can lead to poor growth, even though an adequate diet is being consumed, because of altered use of nutrients. For example, among prepubertal and early pubertal boys, obesity appears to be associated with decreased bone strength in the lower extremities (Falk and colleagues, 2008). Because the human is a social being, appropriate interaction is important for emotional growth and development. Food often serves as a social link, such as at mealtimes (see Figure 1-3). Children should eat as part of a family unit, ideally at the table. Eating with others can stimulate appetite and reinforce that eating is a pleasurable experience. Development of social skills around the table is an important life skill. Children need a variety of nutrients to support growth and development. Zinc and folic acid are crucial for growth to occur. A variety of vitamins and minerals are needed to support bone growth. The B vitamins and omega-3 fatty acids are essential for neurologic health. By following the guidelines of MyPyramid.gov with an emphasis on high-fiber plant-based foods, including whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, and nuts, a good foundation of nutrient intake will occur. When milk (low-fat for over the age of 2 years) and other high-protein sources are included, all needed nutrients can be provided. See also Chapter 1 for the foundation of a healthy diet and the DRI table at the back of the book. The major role of protein is to build and repair body tissues. Protein needs as based on body weight are the highest in infancy and slowly decline with age, although a slight increase occurs late in life (see Table 12-1 and Chapter 13). The total amount of protein is greater as weight and stature increase. Thus it may seem that a young child needs less protein than an adolescent, but based on grams of protein per pound, the child has a higher need. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein reflects the total amount of protein required (see the back of the book). Various factors will affect individual protein needs. For example, the protein requirements of 14-year-old male athletes are above the RDA for nonactive male adolescents at 1.4 g/kg of body weight (Boisseau and colleagues, 2007). Consuming sufficient kcalories is important to ensure protein is used for its building purposes, rather than as a fuel source. Avoiding excess kcalories helps to prevent the development of obesity. Kcalorie needs have been determined for the various ages and weights (see Table 12-1 for younger children). Individual requirements may need to be modified from these general guidelines. For older children the following calculations approximate kcalorie needs: • 80 kcal/kg of body weight for prepubescent children • 45 kcal/kg of body weight for active adolescent males • 38 kcal/kg of body weight for active adolescent females The Adequate Intake (AI) for fluids for children is about 2.5 L or more (see the back of the book). Individual calculations can be undertaken (see Table 12-1). A child who has constipation should be assessed for fluid intake as a possible cause. For athletic children the fluid needs are greater based on various factors such as air temperature and body size. Children involved in endurance sports should have their weight measured both before and after a prolonged training or even an athletic practice of short duration during hot weather. This will help determine fluid needs for individual children (see later section on athletics). In general the quality of the diet is appropriate in the United States to support growth and development of children. This is reflected in the height increase among children that has occurred beginning in the 1940s and the more recent rise in heights since the 1970s. There has been an average increase of about 1 inch between birth cohorts between 1971 and 2002 (Komlos and Breitfelder, 2008). A study among preschoolers found that consumption of grains, fruits, and vegetables increased from 1977 to 1998, but added sugar and juice intake also increased (Kranz, Siega-Riz, and Herring, 2004). Excess intake of sugar and juice can result in excess caloric intake, leading to obesity. It is anticipated that the recent downturn in the economy and the increase in food prices, fuel, and other costs of living will have an adverse impact on intake of fruits and vegetables and other low-processed food sources. One study found almost one half of toddlers consumed all meals and snacks at home, whereas another half ate at least one meal or snack away from home, and about 1 in 10 ate a meal or snack at day care. The fewest average kcalories at lunch were from home (about 280 kcal), whereas the most were at day care (about 330 kcal). However, lunches eaten at day care were significantly higher in nutrients from milk (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, and vitamins B2 and D) compared with those eaten at home or away. Meals eaten away from home were higher in average intake of trans fat, with French fries being the most frequently consumed item by over one third of toddlers. About 3% of toddlers consumed carbonated beverages at home whereas five times this amount did so away from home, and no carbonated beverages were consumed at day care. Snacks generally focused on water, milk, 100% juices such as apple juice or fruit-flavored drinks, crackers, and cookies (Ziegler and colleagues, 2006). With the rise in childhood obesity, the intake of 100% fruit juice and sweetened fruit drinks is being considered a cause. However, on average, preschool children were found to drink less than 6 oz/day of 100% fruit juice. Other sweetened beverages were associated with an increase in the total kcalories, but this was not reflected in an increased body mass index (BMI). It may be that over time the increased kcalories from sweetened beverages contribute to obesity. It also has been found that, on average, preschool children drank less milk than the recommended amount of 16 oz/day. Less than 10% of children over 2 years of age drank low-fat or skim milk as recommended to reduce risk of adulthood cardiovascular disease (O’Connor, Yang, and Nicklas, 2006). According to the 1999-2002 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), only 2- to 3-year-olds met the MyPyramid recommendation for milk intake (Kranz, Lin, and Wagstaff, 2007). There also can be nutritional problems from excess milk intake when it displaces other foods in the diet. A 4-year-old girl with brittle, dry hair leading to hair loss was found to be healthy based on laboratory testing, but her diet revealed a strong preference for milk. This led to the suspicion of zinc deficiency, and with supplementation of 50 mg daily, her hair loss stopped after 3 weeks, and her hair was normal by the fourth month of supplementation (Alhaj, Alhaj, and Alhaj, 2007). Children can develop milk anemia as well, with milk displacing foods high in iron. There are children who do not meet their nutritional needs for optimal growth and development. Among preschoolers in nine child-care centers in central Texas, 3-year-old children were found to have adequate intake of fruits and meat or alternatives but did not meet the goal of two thirds of the recommended servings for grains, vegetables, and dairy. Intakes at home did not compensate for lack of grain and vegetable consumption during child care (Padget and Briley, 2005). One study of 3-year-olds found that snack foods, desserts, and pizza contribute approximately one third of total daily kcalorie intake (Van Horn and colleagues, 2005). Many preschoolers do not meet the goal for fiber of “age plus 5,” and most lacked the 14 g/1000 kcal of energy consumed (Kranz and colleagues, 2005). A significant number of young children use vitamin supplements. Excess intake may result. For apparently healthy children it is recommended to base guidance on use of supplements on dietary habits to avoid inadequate or excess intake (Eichenberger Gilmore and colleagues, 2005). Health care professionals should educate caregivers of infants and toddlers about the importance of foods and promotion of lifelong eating habits for short-term growth and development and lifelong health rather than focusing on just nutrients (Fox and colleagues, 2006). The BMI for children is still the same mathematic calculation as used for adults (refer to Chapter 6). However, for children the calculated BMI number is then put onto an age-based growth chart to assess the percentile number. The BMI percentile is used to assess a child’s level of adiposity. The website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides a multipage chart to determine BMI for young children (see Appendix 1 on the Evolve website for the website address). If children have a BMI over the 85th percentile, they are considered overweight. A high BMI indicates the child is consuming too many kcalories for his or her individual needs. One concern with this is the increased likelihood that these children will become overweight adults. In the Bogalusa Heart study, overweight 2- to 5-year-olds were over four times as likely to become overweight adults as children with a BMI under the 50th percentile (Freedman and colleagues, 2005). On the other hand, children with a BMI under the 25th percentile may be having inadequate kcalorie intake, which can lead to stunted bone growth. Length (lying in a recumbent position) or height (a measurement when the child is standing) is assessed by age. A child who is under the 10th percentile in height or length is assumed to have inadequate nutritional intake or a medical problem interfering with use of food nutrients to support growth. This is particularly true if a child or adolescent’s growth “falls off the curve” (Figure 12-4). A child who is not growing in height to allow “following the curve” should be assessed by a registered dietitian for possible nutrient inadequacies. The continuation of healthy eating into young childhood is enhanced through positive eating experiences and exposure to a wide variety of foods by the end of the first year of life (see Chapter 11 for infant feeding guidelines). Toddlers can become difficult at mealtimes because of issues of independence. Choice is always useful, from the toddler stage through the elder years. The use of structured choices with meal choices works well with toddlers. For example, the parent or caretaker might ask, “Would you like carrots or cantaloupe for lunch today?” This affords the toddler a feeling of independence while still encouraging the child to include adequate vitamin A intake. If the child resists the choices offered and asks for something else, the caretaker can reply, “No, that is not the choice. Would you like the carrots cut into strips or cooked, or do you want to help make melon balls with the cantaloupe?” Having children take their own portion from a serving dish further helps develop a sense of autonomy and interest in eating a variety of foods. The one-taste rule is also helpful, especially when it is explained that learning to like new foods takes time. Focus on the positive: “Try just one taste, and if you like it you can have more.” Helping toddlers and preschoolers to have positive experiences with eating will help maintain good eating habits through their later years. It also is important that parents or other caretakers use common sense and follow the MyPryamid food guidelines. One case study of scurvy (refer back to Chapter 3), which is extremely rare in modern times, was found with an otherwise apparently healthy 2-year-old white girl. Symptoms that brought her for medical assessment included refusal to walk because of leg pain, irritability, sleep disturbance, and malaise. Physical examination revealed pale, bloated skin with swollen gums and loosening of a few of her teeth. Dermatologic findings included xerosis (abnormal dryness of eyes or mouth) and multiple scattered ecchymoses (discoloration of the skin similar to a bruise due to hemorrhage). This was due to adherence to an organic diet recommended by the Church of Scientology that included a boiled mixture of organic whole milk, barley, and corn syrup with no fruits and vegetables (Burk and Molodow, 2007). One goal for young children is the “age plus 5” goal for fiber intake. In other words, for a 2-year-old toddler, the goal would be 7 g of fiber per day. Achieving this goal will help with bowel management, but more importantly will help with growth and development. As reviewed in Chapters 2 and 3, fiber-based foods are high in a variety of vitamins and minerals necessary to support health in young children. As children grow, their eating habits change. The attraction to sweet and the rejection of bitter and sour tastes become more pronounced until there is a decreased taste perception in adulthood. Exposure to a variety of foods helps the child develop a preference for a variety of flavors. This process begins in utero via the amniotic fluid (Nicklaus, Boggio, and Issanchou, 2005b). Exposing the toddler and young child to a variety of vegetables can help develop acceptance into older ages. Among toddlers and preschoolers, simple foods are favorites (Table 12-2 and Figure 12-5). Mixed foods are generally unpopular with this age-group. Differences in food textures interest children. Each meal might include something soft (such as macaroni and cheese), something chewy or crunchy (such as pineapple chunks and thinly cut carrot sticks), and something dry (such as peas). Small portions of a variety of foods at a meal can enhance satiety—the recognition of hunger being satisfied. Table 12-2 Age-Related Childhood Food Guidelines Snacks should be planned to enhance the nutritional value of the diet (Box 12-1) while decreasing risk for dental caries (Box 12-2). Snacks should be served at least 1 hour before meals, but ideally 2 to 3 hours in order to allow sufficient appetite for foods served at mealtime. However, a compromise may be needed if the child is very hungry. A premeal snack before dinner can be considered an appetizer. Good choices for premeal snacks include a dish of peaches and/or yogurt, both nutritious for the young child and easily digested. • Wanting foods plain, with no sauces and not mixed together • Varying interest and lack of interest in food, with appetites that go up and down • Food jags—eating only a few foods day after day or week after week until the next food jag starts Keeping a record of food portions may help to allay parents’ fears that their child is not eating enough. Being able to see the whole day or a whole week very often makes it apparent that the child is eating the recommended food servings to support growth and development. Recommended amounts of foods for toddlers and preschoolers can be found in Table 12-3. This knowledge, in addition to a comparison of the child’s growth with a growth chart, can help calm parents’ fears of nutritional inadequacy. A healthy appearance and high levels of energy in children provide further evidence of good nutritional status (Figure 12-6). Table 12-3 Pattern of Feeding for Toddlers and Preschool-Age Children aIncludes whole milk, low-fat milk, skim milk, cultured buttermilk, or flavored milk made from these types of fluid milk, which meet state and local standards. bOr an equivalent serving of an acceptable bread product made of enriched or whole-grain meal or flour. c d eOr an equivalent quantity of any combination of foods listed under meat and meat alternates. fCooked lean meat without bone. gMust include at least two kinds. From U.S. Department of Agriculture: A planning guide for food service in child care centers, FNS-64, Washington, DC, Food and Nutrition Service. Modeling good food habits is also beneficial. One study found that mothers who consumed more fruits and vegetables were less likely to pressure their daughters to eat and had daughters who were less picky and consumed more fruits and vegetables. It is advised that parents focus less on “picky eating” and more on modeling fruit and vegetable consumption for their children (Galloway and colleagues, 2005). Picky eating can be related to food textures. Children with tactile defensiveness generally have a fair to poor appetite. They may hesitate to eat unfamiliar foods, may not eat at other people’s houses, or may refuse to eat some foods because of smell and temperature. These children may gag when eating. However, it is felt that tactile or oral defensiveness can be treated with a team approach of health professionals (Smith and colleagues, 2005). Attempting to force a picky child to eat can backfire. An authoritarian feeding style was found to negatively affect children’s vegetable intake (Patrick and colleagues, 2005). The manner in which food is offered is fundamental to the development of interest in a variety of nutritious foods. If you reflect for a moment on the types of holiday foods promoted, such as chocolate on Valentine’s Day and candy at Halloween, you will quickly realize the value our society places on food. However, it is possible to promote nutritious foods. Kiwi fruit might be offered in Easter baskets and dried fruit offered at Halloween. As described previously, one of the best methods to promote positive food habits in children is observation of parental intake. A consistent marker for infants at risk for poor diet quality is having a mother who skipped breakfast and omitted fruits, vegetables, or dairy products (Lee, Hoerr, and Schiffman, 2005).

Growth and Development Issues in Promoting Good Health

WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF NUTRITION FOR OPTIMAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT?

GROWTH

DEVELOPMENT

Calories

≤10 kg

100 kcal/kg

10-20 kg

1000 kcal for first 10 kg + 50 kcal/kg > 10 kg

>20 kg

1500 kcal for first 20 kg + 20 kcal/kg > 20 kg

Protein

≤ 6 months

2.2 g/kg

6-12 months

2.0 g/kg

1-10 years

1.8 declining to 0.8 g/kg

Fluids

≤10 kg

100 mL/kg

11-20 kg

Additional 50 mL/kg > 10 kg

≥21 kg

Additional 25 mL/kg > 20 kg

≥16 years through childhood

40 mL/kg

WHAT ARE NUTRITIONAL NEEDS OF CHILDREN?

Role of Protein in Growth and Development

Kilocalorie Needs

Fluid Needs

WHAT IS THE NUTRITIONAL STATUS OF U.S. CHILDREN?

HOW IS NUTRITIONAL STATUS OF CHILDREN ASSESSED WITH GROWTH CHARTS?

WHAT ARE FEEDING MANAGEMENT CONCERNS FOR CHILDREN?

IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS IN FEEDING THE TODDLER AND PRESCHOOL-AGE CHILD (1 TO 5 YEARS OLD)

AGE (YEARS)

SUGGESTIONS

1 to 2

Provide plain, simple finger foods; avoid foods that are choking hazards or cut into very small pieces, and use foods that may be swallowed safely.

Place small amounts on the plate (about 1 tbsp of each food for each year of child’s age).

Provide cups that do not tip easily and have handles, large-handled silverware, and plates with edges (for pushing food against); show toddlers by example how to use utensils, and provide foods that are easy to manage with utensils.

Trust child’s hunger cues because appetite can vary from day to day.

2 to 3

Encourage the “one-taste” rule to expose children to new foods but do not force child to eat.

Make mealtimes pleasant and enjoyable.

Offer structured food choices to allow for a growing sense of independence.

Recognize that food jags (eating the same food day after day) are common at this age and beyond.

Continue to increase the variety of foods offered but with continued attention to avoidance of choking hazards.

3 to 5

Begin to include the child in food shopping (the young child can recognize numbers on food labels; give guidelines such as cereals with no more than 6 g of sugar per serving).

Include the child in simple cooking techniques such as stirring and pouring.

Avoid using food as a bribe or as a reward.

Continue to increase the variety of foods offered but with continued attention to choking hazards.

5 to 10

Continue to provide breakfast, which is especially important for better school performance.

Help the child categorize foods into groups of the MyPyramid.

Be sensitive to the effects of food advertising; help the child understand that many foods advertised are high in fat and sugar.

10 to 18

Recognize that increased body fat often precedes puberty.

Be sensitive to the influence of friends on food and beverage choices.

Provide information on healthy food choices at fast-food restaurants and for snacks.

Help the child find time to eat breakfast and to eat around sports and school events.

MEAL

CHILDREN 1 TO 3 YEARS

CHILDREN 3 TO 6 YEARS

Breakfast

Milk, fluida

c

c

c

c

Juice or fruit

c

c

c

c

Cereal or bread, enriched or whole-grainb

cc

cc

cd

cd

slice

slice

slice

slice

Midmorning or Midafternoon Supplement

Milk, fluida, or juice or fruit or vegetable

c

c

c

c

Bread or cereal, enriched or whole-grainb

slice

slice

slice

slice

c

c

cd

cd

Lunch or Dinner

Milk, fluida

c

c

c

c

Meat or meat alternatee

Meat poultry, or fish, cookedf

1 oz

oz

oz

Cheese

1 oz

oz

oz

Egg

1

1

Cooked dry beans and peas

c

c

c

c

Peanut butter

1 tbsp

2 tbsp

Vegetables and fruitsg

c

c

c

c

Bread, enriched or whole-grainb

slice

slice

slice

slice

c (volume) or

c (volume) or  oz (weight), whichever is less.

oz (weight), whichever is less.

c (volume) or

c (volume) or  oz (weight), whichever is less.

oz (weight), whichever is less.

Developing Sound Food Values

Growth and Development Issues in Promoting Good Health

tsp) or less of sugar; an additional guideline of 2 g or more of fiber will help meet the need for whole grains in the diet.

tsp) or less of sugar; an additional guideline of 2 g or more of fiber will help meet the need for whole grains in the diet.