What are the salient points to obtain from the history and examination?

History

What (if any) thyrotoxic symptoms are present?

History and amount of weight loss.

When was the lump first noticed? Has it increased in size and if so how quickly? Is it painful?

Any difficulties with swallowing or change in quality of voice?

Is there a past medical history (PMH) of thyroid disease or autoimmune disease?

Any history of radiation exposure?

Is there a family history of thyroid disease or head and neck cancer?

Examination

Is she thyrotoxic?

Any evidence of cardiac compromise? This includes atrial fibrillation and/or signs of heart failure.

Are signs of thyroid eye disease present?

Goitre? Is it tender/diffusely enlarged?

Is the nodule palpable? Is it mobile/fluctuant/hard?

Is lymphadenopathy present?

Does the patient have pre-tibial myxoedema?

What are the factors associated with an increased likelihood malignancy in a thyroid nodule?

History of neck irradiation in childhood

FH of hereditary thyroid carcinoma (MTC, PTC, MEN 2)

Male

Age (<20 or >70)

Firm, hard and fixed nodule or rapidly growing nodule

Cervical lymphadenopathy

Persisting dysphonia, dysphagia or dyspnoea

Other: Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (lymphoma), polyposis coli

What are the features of malignancy in a thyroid nodule on ultrasound examination?

Hypoechoic and solid nodule

Irregular margins

Microcalcification

Increased and/or chaotic vascularity

Presence of cervical lymphadenopathy or extra-capsular growth

The patient tells you that she has had classical thyrotoxic symptoms for 8–10 weeks and had lost approximately two stone in weight over 4 months. She first noticed the lump in her neck about 6 months ago and does feel that it has become more noticeable. She has a PMH of post-menopausal osteoporosis for which she takes alendronate weekly. She has no relevant family history.

On examination you note that she is tremulous with moist palms. She has a regular tachycardia (120 bpm) with no evidence of heart failure. She has no signs of active thyroid eye disease. The thyroid is moderately and diffusely enlarged with a palpable nodule within the right lobe of the thyroid which is non-tender and mobile. There is no cervical lymphadenopathy.

What are the differential diagnoses and how would you proceed at this stage?

1.

Toxic adenoma

2.

Graves’ disease with a simple nodule

3.

Toxic multinodular goitre

4.

Graves’ disease with a cold nodule, which may be malignant

How would you manage this patient?

The overriding issue at this stage is to treat this patient’s hyperthyroidism and the symptoms related to this. Anti-thyroid medication such as carbimazole 40 mg od along with a beta-blocker (propranolol 80–160 mg bd) would be the initial treatment option. Longer term management will vary significantly depending on the final diagnosis and so further investigation is warranted at this stage. A thyroid radionuclide uptake scan will indicate if the nodule is “hot” or “cold” and provide useful information to aid the diagnosis. Thyroid function tests (TFTs) should be repeated 4–6 weeks after commencing treatment and reviewed in clinic with the results of the uptake scan.

In her follow up visit, the patient reports an improvement in her symptoms and her weight loss has plateaued. Her repeat TFTs are as follows:

The thyroid radionuclide uptake scan is reported:

The thyroid radionuclide uptake scan is reported:

The nodule within the right lobe of the thyroid does not take up the radio-isotope, whereas within the remainder of the thyroid tissue there is increased uptake.

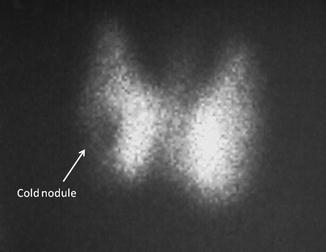

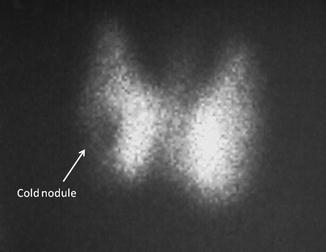

The picture is consistent with Graves’ disease with a non-functioning nodule within the right lobe of the thyroid (Fig. 4.1).

Fig. 4.1

Thyroid uptake scan demonstrating increased uptake within most of the thyroid tissue, with an area of reduced uptake within the right lobe indicating a “cold” nodule

The diagnosis is now suggestive of Graves’ disease with an indeterminate thyroid nodule that requires further investigation.

How common are thyroid nodules? What is the significance of the combination of Graves’ disease and thyroid nodules?

The presence of thyroid nodules in the general population is common, with a prevalence of around 5 %, which can increase to 30–40 % when ultrasound is used to visualise the thyroid, and which is consistent with autopsy studies [1]. The causes of thyroid nodules are shown in Table 4.1. Thyroid cancer is rarer than nodules and accounts for 1–2 % of all cancers. The link between Graves’ disease, thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer has been the subject of much debate. Palpable nodules are present in 10–15 % of Graves’ disease patients, two to three times higher than in the general population [1], and nodules may also develop de novo during the course of the disease [2]. In terms of malignancy and Graves’ disease, the overall risk is approximately 5 % [3–5]; however, this risk is greatly increased in the presence of cold, palpable nodules, ranging from 15 to 48 % [3, 4, 6]. The malignancy rate of palpable nodules within the general population is around 5 %, suggesting that thyroid nodules associated with Graves’ are at increased risk of developing differentiated thyroid carcinoma than nodules within euthyroid individuals. Malignant nodules also appear more aggressive in Graves’ disease, presenting at a more advanced staged and associated with a worse outcome than tumours in matched euthyroid individuals [7, 8].

Table 4.1

Causes of thyroid nodules

Benign (90 % of nodules) | Malignant (10 % of nodules) |

|---|---|

Benign nodular goitre | Papillary carcinoma |

Follicular adenomas | Follicular carcinoma |

Simple or haemorrhagic cysts | Hurthle cell carcinoma |

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis | Poorly differentiated carcinoma |

Medullary carcinoma | |

Anaplastic carcinoma | |

Primary thyroid lymphoma | |

Sarcoma, teratoma and miscellaneous tumours | |

Metastatic tumours

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|