Epidemiology

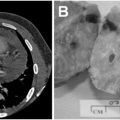

The prevalence of goitres and thyroid nodules was reported as 15% by the Whickham survey in North East England. Goitres are clinically visible in 7% of the population (Fig. 4.1) and are palpable (and not visible) in 8%. They are four times more common in females. Prevalence increases with age, iodine deficiency and previous exposure to ionizing radiation. The Himalayas and the Andes are the most important goitrous areas in the world today. Iodine deficiency is also seen in central areas of Asia, Africa and Europe.

Fewer than 5% of thyroid nodules are cancerous. Thyroid nodules are more likely to be cancerous in males. However, as thyroid nodules are more common in females, they are more frequently affected by thyroid cancer than males. The challenge for the endocrinologists is to identify those few patients who have cancerous thyroid nodules.

Clinical presentations

A mass in the neck noticed by the physician, the patient or relatives may be the only presenting complaint.

Features in the history and examination that raise the suspicion of malignancy include:

- age < 20 or > 60 years

- recent rapid enlargement of a thyroid nodule

- local compressive symptoms: dysphagia, dyspnoea, hoarseness, stridor

- family history of thyroid cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN)

- history of exposure to radiation

- lymphadenopathy.

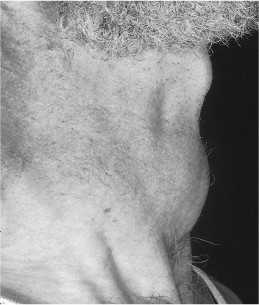

Figure 4.1 Goitre.

In addition, a history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis raises incidence of lymphoma. Papillary thyroid carcinoma may be associated with some rare inherited syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis, Gardner’s syndrome (autosomal dominant disease characterized by gastrointestinal polyps, multiple osteomas, skin and soft tissue tumours) and Cowden’s disease (an autosomal dominant condition characterized by multiple hamartomas and an increased risk of early-onset breast and thyroid cancer).

Thyroid examination should include the following steps:

- Inspection : ask the patient to swallow (the goitre moves upward).

- Palpation : examine the goitre with the patient swallowing—the goitre moves upward. This may be lost in anaplastic carcinoma and Riedel’s thyroiditis (a rare chronic inflammatory disease of the thyroid gland characterized by a dense fibrosis replacing normal thyroid parenchyma, which results in a ‘woody’ goitre). Determine the size, whether the goitre is nodular or diffusely enlarged, soft or hard, or tender (e.g. in subacute thyroiditis or bleeding into a cyst) and the presence of lymph nodes.

- Percussion of the upper mediastinum (dull in retrosternal goitre).

- Auscultation: for a bruit (in hyperthyroidism) and inspiratory stridor (in cases of tracheal compression).

- Determination of thyroid status (look for features of hypothyroidism or thyrotoxicosis).

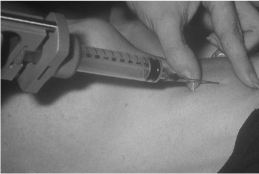

Figure 4.2 Fine needle aspiration of a thyroid nodule.

Investigations

Laboratory findings

Thyroid function tests

Thyroid function tests (thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH] and free thyroxine [T4]) should be requested to exclude thyrotoxicosis and hypothyroidism. Serum thyroglobulin levels are increased in both benign and malignant nodules, and can only be used in the follow-up of patients with treated differentiated (papillary and follicular) cancers. Calcitonin should be measured when medullary cell carcinoma is suspected (usually after fine needle aspiration cytology results).

Patients with suspected tracheal obstruction should have respiratory flow—volume loop studies.

Fine needle aspiration and cytology

All patients should have fine needle aspiration of the thyroid nodule for cytological examination (Fig. 4.2).

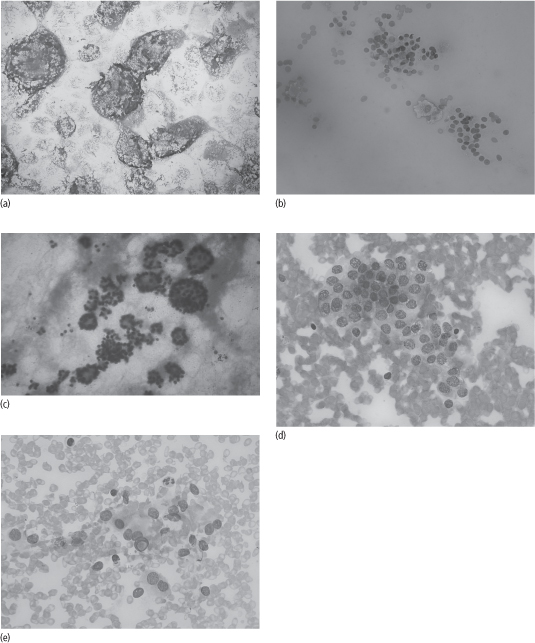

Figure 4.3 Cytological specimens from fine needle aspiration of thyroid nodules. (a) Non-diagnostic: thick blood with no thyroid cells (Thy1). (b) Non-neoplastic (Thy2), (c) Follicular neoplasm: may be an adenoma or carcinoma (Thy3). (d) Suspicious of malignancy (Thy4). (e) Diagnostic of malignancy (Thy5)

The cytologist’s report may be one of the following (Fig. 4.3):

- Non-diagnostic

- Non-neoplastic (abundant colloid, features compatible with multinodular goitre or thyroiditis)

- Follicular lesions: adenoma or carcinoma

- Suspicious of malignancy

- Diagnostic for malignancy.

Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration should be performed where there is high suspicion of malignancy (history of radiation, MEN type 2 (see Chapter 32), suspicious ultrasound features, presence of cervical lymph nodes).

Imaging

There are no ultrasonographic findings that are specific for thyroid carcinoma. However, features that raise suspicion of malignancy include hypoechogenicity, irregular border, microcalcifications and increased colour Doppler flow.

A radioisotope uptake scan should be performed in all patients with suppressed TSH. 99Technetium pertechnetate is more commonly used than 123iodine as it is cheaper and more readily available. Some endocrinologists also perform a thyroid uptake scan in cases of indeterminate fine needle aspiration cytology (10% of cases).

Malignant nodules are more likely to be cold (i.e. not to take up radioisotope). However, most (80%) cold nodules are benign (e.g. colloid nodules, haemorrhage, cysts or inflammatory lesions such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) (Fig. 4.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree