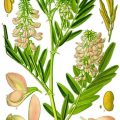

Fig. 10.1

Metabolic constraint on gestation length and fetal size. (Y axis). Fetal energy demands (green line, kcal/day) increase exponentially during gestation (X axis). Maternal energy expenditure (red line) rises during the first two trimesters but reaches a metabolic ceiling in the third, as total energy requirements approach 2.0× basal metabolic rate (4)

To summarise extensive reviews on pregnancy energy metabolism, among which one is by Nancy Butte [3], one can depict glucose and insulin changes as follows. In early pregnancy, basal glucose concentrations and hepatic basal glucose production do not differ significantly from pre-pregnancy values; muscle and hepatic sensitivity to insulin is normal. Insulin incretion is normal or even increased in its first minute response to glucose.

By the third trimester, basal glucose concentrations go 10–15 mg/dL below pre-pregnancy levels (0.56–0.83 mmol/L), and insulin is almost twice the concentration. Postprandial glucose concentrations are significantly elevated and the glucose peak is prolonged. These changes are paralleled by an increase of 16–30 % in basal endogenous hepatic glucose production to meet the increasing energy needs of the placenta and fetus. In late gestation these changes are driven by the combination of rising concentrations of human chorionic gonadotropin, prolactin, cortisol and glucagon that overall exert anti-insulinogenic and anti-lipolytic effects to achieve availability of alternative fuels, especially fatty acids, by peripheral tissues.

Changes in hepatic and adipose metabolism alter lipids profile as well. In pregnancy we observe a steady increase in triglycerides; cholesterol, with a higher LDL rise; fatty acids; lipoproteins; and phospholipids. The HDL triglycerides ratio goes up from 2 to 4–5, pretty in the range of dyslipidemia in non-pregnant women. These are good news for the fetus that can claim its share of glucose and amino acids while the mother diverts her energy metabolism with mobilisation of lipid store.

10.2 The Paradox of Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy

The variable prevalence of gestational diabetes is a consequence of mixed effects of different diagnostic criteria in different populations: American Diabetes Association, 2–19 %; Carpenter and Coustan, 3.6–38 %; National Diabetes Data Group, 1.4–50 %; and the World Health Organization, 2–24.5 % [4]. According to the criteria of the international consensus of the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study, this prevalence ranges around 16 % in a large mixed population of 23 thousand women recruited in different countries and ethnically diverse, with 48 % white Caucasians, 12 % black, 29 % Asian/Oriental and 8 % Hispanic/mestizos.

Indeed, this huge variability appears to be the obvious clinical result of two evidences: first, there is a continuous positive linear association between maternal glucose and increased fetal birthweight, as well as fetal hyperinsulinaemia [5] and eventually abnormal short-term and long-term outcome (Fig. 10.2); second, there is a strict association between lifestyle, macro-ethnicity and metabolic syndrome, altogether major risk factors for insulin resistance, and abnormal lipid and carbohydrate metabolism.

Fig. 10.2

Birthweight >90th percentile across glucose categories (mg/dL). Glucose category 1, <75; category 2, 75–79; category 3, 80–84; category 4, 85–89, category 5, 90–94, category 6, 95–99; category 7, > 100 mg/dL. Blue line = fasting glucose values; yellow line = 1 h glucose values; red line = 2 h glucose values (2)

These aspects compose a puzzle where pieces of epidemiology and pieces of diagnostic tests are confronted with the objective to fit the final design of chronic diseases: changing thresholds in different or mixed populations might cause huge variations in prevalence estimates.

But why this puzzle should happen in the 9 months span of a pregnancy, not at all a chronic scenario?

A dominant party of Western medicine look at this phenomena from the point of view of higher prevalence of the disease (ICD-9, 648.83) therapy, health-care costs and hence insurance costs: thresholds are brought as high as decently possible, the prevalence of the disease reduced, and its costs cut [4]. Others, when faced with chronic degenerative diseases, favour prevention. Low screening thresholds yield the opportunity to intervene before the full-blown disease is established.

We totally embrace the following vision of the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine: “There are three times during a woman’s life that she accesses the health care system on a regular basis and is seen by a trained health-care provider: as an infant, for pregnancy and postpartum care and when she develops a chronic disease. Given that chronic diseases like cardiovascular disease are usually decades in development, for the majority of women of reproductive age, pregnancy and the postpartum provides a new early window of opportunity to identify risk factors and improve their long-term health”.

10.3 Gestational Diabetes: A Clinical Phenotype of an Accelerated Metabolic Syndrome in Pregnancy

10.3.1 Anti-insulin Effects of Pregnancy

The anti-insulin effects of pregnancy are a well-known history. At the end of the day, a few weeks with high glycaemic values do not represent a health problem for the adult woman and a large baby can be safely delivered by caesarean section, and its possible neonatal metabolic disturbances might be safely treated in any hospital setting. So what? This first player in the unbalanced “metabolism” frequently covers in the clinical practice the more complex picture that is associated with maternal gestational diabetes and promotes a critical intrauterine environment.

10.3.2 Dyslipidaemia

The role of lipids has been frequently overlooked by obstetricians in gestational diabetes. Indeed, dyslipidaemia is a constitutional part of metabolic syndrome in adults and, more specifically, in type 2 diabetes in a way that resemble normal gestation: dense LDL and triglyceride increases versus low level of HDL. Elevated levels of free fatty acids (FFA) cause insulin resistance in muscle and liver cells. Saturated fatty acids are among the most detrimental of FFA, being the main culprit of insulin resistance and inflammation. On the other hand, FFAs act on the beta cell of the pancreas to stimulate insulin secretion, both directly improving the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and potentiating glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. To some extent, this counterbalances peripheral insulin resistance.

10.3.3 The Microbiota

A third player comes on stage to promote an accelerated metabolic syndrome in pregnancy. The pregnant state modify the intestinal microbiome [6] in a way that faeces of third-trimester mothers showed increased signs of inflammation and energy loss. In a germ free mice, transplant of faeces of third trimester human pregnant women, but not first trimester pregnant women, increased adiposity, insulin resistance and inflammation were determined (Fig. 10.3).

Fig. 10.3

Impact on inflammation and glucose metabolism on germ-free mice, of intragastrically administered inoculum of faeces from the first trimester (T1 – green bars and line) and third trimester (T3 – grey bars and line) human donors (6)

10.3.4 Unbalanced Western Supermarket-Style Nutrition

The final fourth player of this picture introduces us to the substantial impact of lifestyle in nutrition in Western societies of lipid metabolism. The original balance of n-6 (linoleic acid metabolised to arachidonic acid) and n-3 (alfa linolenic metabolised to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)) essential fatty acid that at the best of our knowledge as qualified human diets for at least 160 thousand years in a 2:1 and 1:1 ratio has been dramatically changed in Western diets up to a ratio of 10:1 and 25:1. n-3 essential fatty acids are indeed essential in an array of positive human metabolic pathways [8]. Beyond this, it might be of relevant interest the recent association of n-3 essential fatty acid with the biosynthesis of a specialised family of pro-resolving mediators of inflammation [9] (resolvins, protectins and maresins). This is probably what is needed to soothe the strained insulin receptors and the endothelium.

10.3.5 Macro-Ethnicities

These two latter elements, microbiota and nutrition interact to lessen or increase the risk of the accelerated metabolic syndrome of pregnancy. What is not widely and properly acknowledged in nutritional counselling is the importance of the phenotype of different macro-ethnicities in which this interaction takes place. Asian, mestizos and AmerInds (sometimes defined as Hispanics in North American literature) and Native American women, as compared with white women of Caucasian ancestry, have an increased risk of GDM [10]. The large human migrations from Asia and South America [11] into Europe and the USA and the spread of Western-style diet (Fig. 10.4) have proved that the metabolic syndrome, originally a rare phenomenon in these macro-ethnicities, has become a major health problem both in Western countries and in these original countries [12, 13].

Fig. 10.4

More than 40 million people feed every day similar unbalanced food, frequently associated with a sugary carbonated drink and fried starch. The bread is usually made with wheat flour type 0, added with glucose, rapeseed oil, potato starch and chemical colours. The meat comes from intensive cattle raising, and the part of the cow from which it is minced is an “industrial secret”. The cheese is a complex mix of reconstituted dairy products and artificial colours. A few human dishes are so far from a balanced nutritional profile. A touch of green, less than 20 g in weight, and here we go promoting the metabolic syndrome

A special mention is deserved to slave trade from Western Africa and the fate of these macro-ethnicities in North America and the Caribbean. Agriculture and farming entered East Africa eight thousands years ago. We can trace its slowly spreading south in millennia, thanks to archaeological findings, and the prevalence of lactose persistence in micro-ethnicities of Eastern Africa [14]. When slave trade was started by “colonial powers”, in the sixteenth century, farming products as we know them (protein-rich grains such as wheat, cow milk and dairy products; fat-rich meat from cattle raising) had not yet entered the nutritional profile of black ethnicities of West Africa. The descendants of the forced migration exposed to Western-style diet are even more prone to obesity and abdominal obesity than populations of Caucasian ancestry in whom such a prevalence occurs only in areas of very low income (http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence see maps 2011–2013 of white adults – and maps of Black Adults).

Metabolic syndrome in these macro-ethnicities is not just eating too much but is an accelerated consequence of the mismatch between their genome and their nutritional profile that is even more alien to them than to population of Caucasian ancestry.

All these “players” conjure to make pregnancy a possible pray of an accelerated metabolic syndrome both igniting a trans-generational legacy of diabetes-causing diabetes [15] and signalling the future risk to develop a full-blown type 2 diabetes in the fifth decade [16] up to 11 times the risk of women who did not suffer of GDM.

10.4 The Magic Challenge of Prevention Through Food and Exercise

We all have, somewhere in a box, images of our grand grandparents, not necessarily during wartime: abdominal obesity was then a rare condition if ever existed in a family in two generation spans. That was the waistline then, not only for people of Caucasian ancestry in Europe and the USA but also for Afro-Americans, natives, first-generation Chinese and Asians. In 1950 the average BMI of white Americans was 22.4. In 2012 the average BMI was up to 27.8. Unfortunately Europe and Arabian countries are “catchin’ up” this “Western inequality” very rapidly. Among all variables interwoven in the social fabric that lead to present epidemics of obesity, it is likely that industrial processing of food, food marketing, quantity vs. quality policy and fast food eateries bear the largest responsibility for the epidemics (Fig. 10.4).

Poor food, according to the Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHE) adherence score, overweight and inactivity yield a risk of up to 45 % of developing gestational diabetes in future pregnancies [17]. According to the same study, based on a cohort of 14 thousand, mostly white Caucasian women, the risk of gestational diabetes was 83 % lower (RR 0.17) in women with normal weight, good diet, exercise and no cigarette smoking. This is a proof of principle that gestational diabetes could be preventable just by changing lifestyle and reverting it back to a more “human lifestyle”, nothing more. To make it simple we can summarise the adherence to AHE under the name of prudent diet characterised by a high intake of fruits, green leafy vegetables, poultry and fish. A “poor” diet can be characterised by a high intake of red meat, processed meat, refined grain products, sweets, French fries, pizza, sugary beverages and sugary snacks or Western-pattern diet.

Unfortunately, lifestyle and nutrition cannot be changed at the snap of the fingers or just through a medical consultation. This is why pregnancy and the special compliance that can be nurtured in this delicate frame are a window of opportunity to win bad habits and introduce a healthier lifestyle and nutrition.

10.4.1 Healthy Diet or Healthy Diets?

Troubles begin when one has to enter the field of defining what a healthy diet is. For decades this has been defined just by relative amounts of protein, fats and carbohydrates. Such useless profile avoids to meet the real-world problems where governmental regulatory bodies live under tremendous pressure of the agro-industrial system. A huge amount of literature on dietary prevention and treatment of gestational diabetes came to almost no conclusions until a few years ago [18]. However some pillars can be deducted by good-quality pre-pregnancy studies [10] and by the few more recent studies [19, 20].

According to these studies, the culprit of an increased incidence of gestational diabetes in pre-pregnancy studies are (a) insufficient consumption of vegetables and fruit; (b) refined cereal that deprives the organism of the natural fibre content of these nutrients; (c) sugar-sweetened beverages, sugary snacks and fruit juices; (d) products rich in cholesterol and other animal fats; and (e) overconsumption of red meat and processed meats. The latter item comes to a surprise and requires some explanatory notes. First of all, red meat from farm-raised cattle is rich in cholesterol that was pretty scarce in the game meat of our ancestors; nitrites used in processed meat might be transformed into nitrosamine that might damage the pancreatic beta cell; heating cholesterol-rich meat produced glycated compounds, excess of haem iron in women without iron deficiency, and eventually the pro-inflammatory role of the sialic acid of cell walls of mammalians (N-glycolylneuraminic acid) that differ from human sialic acid by one acetyl compound (N-acetylneuraminic acid) [21]. This latter unwanted interaction of mammalian red meat with our immune system is caused by a single gene mutation that sets human cell membrane apart from anthropoid monkeys and all other mammalians including cattle. This mutation makes the human red cell membrane free from the aggression of the lethal malaria agent, the Plasmodium reichenowi that infects monkeys [22]. However, the continued supplementation of this molecule through diet stimulates a low-grade immune reaction and eventually this alien immunogenic sialic acid might be incorporated in high turnover tissues, such as the endothelium [23].

One single aspect has been sorted out by many studies and requires a proper focus. We know that pregnancy in patients fed on a Western diet induces diabetogenic changes in the intestinal microbiota [6]. The intestinal microbiota modulates the immune system and this might balance the low-grade inflammation of visceral obesity and of term pregnancy. Obviously, negligible supplementation with one billion single-strain bacteria for a negligible number of weeks does not achieve any results in reducing risk factors [24]. Positive results were observed by single trials adopting proper dosage and length of administration [25–27]. In addition to this, preliminary data show how probiotic yogurt can reduce the inflammatory profile in pregnancy [20] as well as it has been proved in non-pregnant adults [28].

The nutritional prevention of gestational diabetes should then be tailored on each woman who requires the assistance of health-care providers.

Macro-ethnicity, cultural values, nutritional traditions and family habits, individual intolerance to food, lactose non-persistence and gastrointestinal signs and symptoms – all these elements should be investigated and become the background for nutritional advice. The healthy plate should accommodate all nutritional balances based on vegetable and fruit carbohydrate oligo elements and fibres, a variety of whole grains, healthy vegetable fats and healthy proteins including a prudent weekly share of fermented dairy products and red meat.

10.5 The Paradox of Hypertensive Diseases of Pregnancy: Preeclampsia

For almost 100 years preeclampsia had been defined by the coexistence of hypertension and proteinuria in a pregnant woman. Eventually, recently major scientific bodies such as the Royal College, the American College and The Canadian Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists picked out foamy urine – or proteinuria as more properly diagnosed by chemical reagents – from the definition of preeclampsia. This syndrome now accommodates a huge variety of signs, clinical conditions and laboratory abnormalities, and some guidelines even include fetal growth restriction to allow for a diagnosis of preeclampsia; others exclude this condition. A more generalized name could probably better fit the whole scenario: hypertensive diseases of pregnancy. Besides guidelines, or ahead of official scientific bodies, single scholars or international working groups, such as the Global Pregnancy CoLaboratory [29], proposed novel strategies to diagnose the different clinical phenotypes and possible different diseases, included unto the huge umbrella of preeclampsia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree