Outline

Tumors of Germ Cell and Sex Cord Derivation

Tumors Derived From Special Gonadal Stroma

Classification, Clinical Profile, and Staging

Fibromas and Sclerosing Stromal Cell Tumors

Sex Cord Tumor With Annular Tubules

Tumors Derived From Nonspecific Mesenchyme

Metastatic Tumors to the Ovary

Key Points

- 1.

Germ cell tumors are classified according to degree of differentiation. Two classes exist: undifferentiated germ cell tumors, which include dysgerminoma and gonadoblastomas, and differentiated tumors, which include all other germ cell tumors.

- 2.

Most germ cell tumors are found in the second and third decades of life.

- 3.

Surgery is the preferred initial approach in the treatment of germ cell cancers.

- 4.

Recurrences usually occur within 2 years of initial diagnosis.

- 5.

Granulosa cell tumors are typically ovarian cancers of low grade.

Germ Cell Tumors

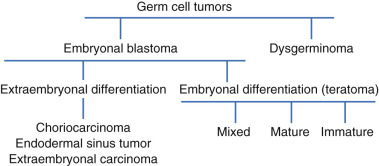

Classification

Ovarian germ cell tumors consist of several histologically different tumor types that arise from primordial germ cells of embryonic gonad and sex-stromal derivatives. This class of ovarian tumors is rare, accounting for 1% to 2% of all ovarian malignancies. The concept of germ cell tumors as a specific group of gonadal neoplasms evolved over the past 5 decades and has become generally accepted ( Fig. 12.1 ). This theory is based primarily on the common histogenesis of these neoplasms and the frequent presence of histologically different tumor elements within the same mass. Additionally, histologically similar neoplasms occur in extragonadal locations along the line of migration of the primitive germ cells from the wall of the yolk sac to the gonadal ridge, and there is remarkable homology between the various tumor types in men and women. In no other group of gonadal neoplasms has this homology been better illustrated. An example of this is the striking similarity between the testicular seminoma and its ovarian counterpart, the dysgerminoma. These were the first neoplasms to become accepted as originating from germ cells. A number of classifications of germ cell neoplasms of the ovary have been proposed over the past few decades. A modification of the classifications originally described by the pathologist Gunner Teilum in the 1950s is shown in Table 12.1 . This schema is similar to that proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO), which divides the germ cell tumors into several groups, including neoplasms composed of germ cells and “sex” stroma derivatives.

| GERM CELL TUMORS |

|---|

|

| TUMORS COMPOSED OF GERM CELLS AND SEX CORD–STROMAL DERIVATIVE |

|

Germ cell tumors are classified according to the degree of differentiation. Two classes exist:

- 1.

Undifferentiated germ cell tumors, which include dysgerminoma and gonadoblastoma

- 2.

Differentiated tumors, which include all other germ cell tumors.

Differentiated tumors are further classified based on whether the tumor differentiates histologically into embryonic or extraembryonic structures. Extraembryonic tumors include choriocarcinoma and endodermal sinus tumors. Embryonal tumors include embryonal carcinoma, polyembryoma, and teratomas, the latter of which may be mature, immature, monodermal, or highly specialized. Dysgerminomas, immature teratoma, yolk sac tumors, and mixed tumors make up more than 90% of all malignant germ cell tumors. Finally, it is important to recognize that germ cell tumors clinically behave in part on whether they are histologically pure, consisting of only one cell type, or mixed. Tumors such as embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and polyembryoma rarely exist in pure form and have a poorer prognosis. The clinical behavior of germ cell tumors typically conforms to the most aggressive histologic subtype present in mixed tumors. Treatment, therefore, should be predicated on this knowledge.

Clinical Profile

Germ cell tumors present at all stages of disease and are typically curable. Germ cell tumors represent 20% of all ovarian ( Table 12.2 ) neoplasms of which 97% are benign and only 3% are malignant. There are no known risk factors predisposing women to germ cell tumors, although most tumors occur in young women. A Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database review of malignant germ cell tumors from 1973 to 2002 revealed the highest incidence of disease in the 15- to 19-year-old age group. Because these tumors occur predominantly in reproductive age groups, it is not surprising that they are encountered commonly during pregnancy. Dysgerminomas and teratomas are the most common germ cell tumors diagnosed during pregnancy or after delivery. Surgical evaluation and treatment, including chemotherapy if necessary, can be safely performed in the second and third trimesters. Although rare reports of familial clustering of ovarian and testicular germ cell tumors have been described in the literature, there is no known syndrome or genetic abnormality conferring susceptibility to germ cell malignancies.

| Type | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Coelomic epithelium | 50–70 |

| Germ cell | 15–20 |

| Specialized gonadal stroma | 5–10 |

| Nonspecific mesenchyme | 5–10 |

| Metastatic tumor | 5–10 |

With respect to race, Asian and black women are affected by malignant germ cell tumors three times as frequently as white women and often have a worse prognosis. For example, SEER database results from 1988 to 2004 revealed improved survival in white women compared with black women, a finding attributable to a more favorable stage distribution and histology in whites. In this study, white patients were twice as likely as black patients to have dysgerminomas and one and a half times less likely to have immature teratomas. Advanced-stage tumors were also more common in black patients. Nevertheless, on multivariate analysis, race was not an independent predictor for survival after controlling for histology and stage of disease. Similarly, Smith et al. evaluated the incidence and survival rates of women with malignant germ cell tumors over a 30-year period from 1973 to 2002. In this study, malignant germ cell tumors were noted more often among Asians and Pacific Islanders and Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics. When women were stratified by race and ethnicity, nonwhite women had a higher incidence of germ cell tumors than whites. The reasons for these racial differences in prevalence and outcomes are unknown.

According to SEER data, germ cell tumors are associated with excellent 5 and 10-year survival rates in excess of 91%. Survival rates are lower for older women and those with advanced-stage disease. Dysgerminomas have the most favorable survival rates among the histologic subtypes. A reduction in the number of women with distant and unstaged disease has been noted throughout the years, which suggests that these tumors are being diagnosed earlier.

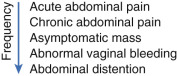

Most of these lesions are found in the second and third decades of life and are frequently diagnosed by finding a palpable abdominal mass, often associated with pain ( Fig. 12.2 ). Except for benign cystic teratoma, ovarian germ cell tumors are usually unilateral, rapidly enlarging abdominal masses that often cause considerable abdominal pain. At times, the pain is exacerbated by rupture or torsion of the neoplasm. One of the classic initial signs of a dysgerminoma, for example, is hemoperitoneum from capsular rupture of the tumor as it rapidly enlarges, although this may occur with any germ cell tumor. Asymptomatic abdominal distention, fever, or vaginal bleeding is occasionally the presenting complaint. Isosexual precocious puberty has also been described, occurring in young patients whose tumors express human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).

The tumors typically present at an early stage and spread by direct extension, seeding abdominal and pelvic peritoneal surfaces, and by hematogenous and lymphatic spread. Hematogenous spread to the lungs and liver parenchyma is more common in germ cell malignancies than in epithelial ovarian cancer, as is lymphatic spread. Many germ cell tumors produce serum markers that are specific and sensitive enough to be used clinically in following disease progression. A detailed discussion of individual tumor markers is presented in the sections on specific tumor types.

Staging

Germ cell tumors should be staged surgically in the same manner as epithelial ovarian cancers and in accordance with the guidelines of the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetrician (FIGO). Because germ cell tumors occur more frequently in young patients, extirpation of the disease involves decisions concerning childbearing and probabilities of recurrence. Adjuvant chemotherapy is the standard of care for women with germ cell malignancies except for those with stage Ia dysgerminoma or stage Ia grade I immature teratoma. Comprehensive staging therefore allows patients to be appropriately risk stratified and selected for surveillance versus adjuvant therapy. The recommended staging procedures for germ cell tumors consists of a laparotomy; a sampling of ascitic fluid if present; cell washings; a careful exploration of the abdomen and pelvic cavity; omentectomy; and random biopsies of the paracolic gutters, pelvic sidewalls, cul de sac, vesicouterine reflection, and diaphragm. If extensive disease is present in the abdominal cavity, omentectomy and cytoreduction to optimal residual disease should be performed if possible. Pelvic and paraaortic lymph node sampling should be performed, but a complete lymphadenectomy is not necessary. Bulky lymph nodes, if present, should be removed. Based on an analysis of SEER data, the prevalence of lymph node metastasis in germ cell malignancies is 18%. Dysgerminomas have the highest prevalence of nodal disease at 28% followed by mixed germ cell tumors at 16% and immature teratomas at 8%. After controlling for age, race, stage, and histology, positive lymph nodes remained an independent predictor of poor survival on multivariate analysis.

Despite the prognostic significance of positive lymph nodes and the obvious benefits of guiding adjuvant therapy, comprehensive surgical staging is frequently not performed. In a paper evaluating compliance with surgical staging guidelines, only three patients of 131 with germ cell malignancies had complete staging performed. Failure to perform recommended lymph node sampling was the most common reason for noncompliance (97%) followed by no omentectomy (36%) and no cytologic washings (21%). The decision to proceed with another operation for patients who have not been staged at their initial surgical procedure is controversial because patients with recurrences can often be salvaged with chemotherapy. According to a study from the Centre Léon Bérard in Lyon and the Institut Curie in Paris, the risk of recurrence was significantly higher (hazards ratio [HR], 4.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5–13.3) in unstaged patients who clinically appeared to have stage I disease and were observed after surgery versus another cohort treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Among the unstaged patients, relapses occurred in five of 13 patients who underwent surveillance but none of the seven patients who received adjuvant treatment recurred. Data from the Pediatric Oncology Intergroup suggest that deviations from standard staging requirements do not adversely affect survival. In this study, the recommended surgical guidelines were seldom followed in this pediatric population, and the 6-year survival rate was 93.3% in girls with stage IV disease.

Laparoscopy is less common in patients with ovarian germ cell tumors given the larger size of these tumors, the solid components they contain, and the risk of tumor spillage and cyst rupture. Shim et al. evaluated laparoscopic management of early-stage malignant nonepithelial ovarian tumors to determine the feasibility and safety of a minimally invasive approach. This study included 20 patients with sex cord stromal tumors (SCSTs) and eight with malignant germ cell tumors. The median primary tumor diameter was 10.4 cm, and laparoscopic pelvic and paraaortic lymph node dissection was performed in nine cases. Tumors were removed through a 10-mm port using an endoscopic specimen retrieval system to prevent tumor spillage. For a mass that did not fit in the retrieval system, hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery was performed. All patients in this study had stage I disease. No intraoperative complications occurred. Five patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. The median follow-up period was 34.5 months during which time one patient recurred and was treated with chemotherapy. No patient died of the disease.

In patients with suspected early-stage disease, laparoscopy may represent a preferred surgical route and in several studies has been shown to be comparable with traditional open procedures. Prado et al. introduced guidelines to apply when considering a laparoscopic technique, such as careful case selection, adequately trained teams, use of an endobag for tumor removal, and minimizing tumor manipulation to decrease rupture of the mass. For advanced stage disease, it may not be feasible to attempt a laparoscopic procedure.

Treatment Options

Surgery is the preferred initial approach in patients with suspected germ cell tumors for both diagnostic and therapeutic intent. The extent of primary surgery is dictated by intraoperative findings and the reproductive desires of the patient. If childbearing has been completed, then a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and hysterectomy are performed in addition to a full staging procedure. However, if preservation of fertility is desired, then every attempt should be made to perform a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging while preserving the uterus and contralateral ovary. The safety of such an approach has been well established in the literature. In select cases such as stage Ia dysgerminoma and stage Ia grade I immature teratoma, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is thought to be curative and is all that is required. All other cases will likely require adjuvant therapy. In all cases of apparent unilateral disease confined to the ovary, the contralateral ovary should be carefully evaluated. Although dysgerminoma is the only germ cell malignancy with a propensity for bilaterality (10%–20% of cases), other histologic subtypes occasionally involve both ovaries. The contralateral ovary, if abnormal, should be biopsied or a cystectomy performed. If the frozen section confirms a diagnosis of malignancy, then the ovary should be removed. Frozen section is highly accurate for nonteratomatous sex cord stromal and germ cell tumors. If the contralateral ovary appears normal, then it should be left alone. Some clinicians have advocated performing a wedge biopsy of a normal-appearing contralateral ovary in cases of dysgerminoma to detect subclinical or microscopic disease. We recommend avoiding wedge biopsy of a normal-appearing ovary because of the potential for surgical complications such as hemorrhage or adhesion formation that may affect future fertility. Boran et al. evaluated pregnancy outcomes, menstrual function, and survival rates of patients after fertility sparing surgery for ovarian dysgerminomas. Twenty-three patients met inclusion criteria and underwent conservative surgical management with a median follow up time of 71 months. Regular menstruation after treatment resumed in 82% of the patients, and three primiparous patients had singleton live births after treatment.

The excellent response of germ cell malignancies to adjuvant chemotherapy has allowed a tailored approach to the surgical management of this disease in women desiring fertility preservation. Although unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be considered the standard procedure in such cases, recently, some clinicians have advocated ovarian cystectomy in select cases of immature teratoma. Beiner and colleagues reviewed eight cases of immature teratoma treated with ovarian cystectomy, including three with grade I, four with grade II, and one with grade III. Five of the eight patients received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. There were no recurrences in 4.7 years of follow-up, and three patients delivered a total of seven babies. The authors concluded that ovarian cystectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy appeared to be satisfactory therapy for early-stage immature teratoma if close follow-up was available, but more studies were needed to evaluate cystectomy alone as a surgical management option. This management strategy should be approached with caution, especially for other histologic germ cell subtypes, which may not share the same prognosis as early-stage immature teratoma.

Patients with bulky disease in the abdomen, pelvis, and retroperitoneum should undergo surgical cytoreduction to optimal residual disease. The literature to support this recommendation comes, primarily, from small retrospective studies. In a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study by Slayton and colleagues, patients with completely resected disease failed subsequent VAC (vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy in 28% of the cases compared with 68% of cases with incomplete resection. In the same study, 82% of patients with bulky residual disease failed chemotherapy compared with 55% with minimal residual disease. Subsequently, the GOG published results showing that patients with clinically nonmeasurable disease after surgery treated with PVB (cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin) remained progression free in 65% of cases compared with 34% of patients with measurable disease. Patients with optimal cytoreduction did better than those with unresectable bulky disease. This study also helped establish the efficacy of cisplatin-based chemotherapy for germ cell tumors. Finally, Williams and colleagues showed that patients with completely resected stage II or III disease treated with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin had similar tumor-free recurrence rates as those with disease limited to the ovary. These studies provide the bulk of evidence to support cytoreductive surgery in germ cell cancers.

In patients with bulky metastatic disease, a normal-appearing uterus and contralateral ovary may be preserved, allowing for future fertility options if desired. Tangir and colleagues reviewed 64 patients with germ cell malignancies treated with fertility-preserving surgery. Ten patients had stage III disease (five IIIc, two IIIb, and three IIIa), and eight of the 10 women successfully conceived. Survival data were not included in the analysis. Zanetta and colleagues evaluated 138 women with germ cell malignancies of all stages treated with fertility-sparing surgery, 81 of whom received adjuvant chemotherapy. Survival was comparable between patients treated with radical surgery and fertility-sparing surgery after a mean follow-up period of 67 months. Similarly, Low and colleagues retrospectively reviewed 74 patients with germ cell malignancies of all cell types treated with conservative surgery. Forty-seven patients were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Fifteen patients had stage III to IV disease. After 52 months of follow-up, patients with advanced disease had a 94% survival rate, comparable to historical survival rates.

In summary, patients with germ cell malignancies should undergo operative evaluation, staging, and cytoreduction. If future fertility is not desired, surgical treatment should be identical to that for epithelial ovarian cancers. If preservation of fertility is desired, conservation of the uterus and contralateral ovary and maximal cytoreduction should be performed if possible. Despite the success of surgical management, surgeons should recognize the excellent response of these tumors to chemotherapy when aggressive and potentially morbid resections of metastatic and retroperitoneal disease are considered.

Surveillance for Stage I Tumors

As previously noted, historically, in the gynecologic oncology literature, only patients with stage Ia dysgerminoma or stage Ia grade I immature teratoma of the ovary have been treated conservatively without adjuvant chemotherapy. Although the recurrence rate approaches 20% for these patients, curative chemotherapy is administered after the recurrence. The recommendation for adjuvant treatment of any nondysgerminomatous histology is at odds with contemporary management practices of testicular germ cell tumors in which all patients with stage I disease are followed with observation only as standard practice. Rustin and Patterson published provocative data on their 37-year experience with a liberal surveillance policy for patients with stage I germ cell tumors of the ovary. In their first report, 24 patients with stage Ia germ cell tumor (nine dysgerminoma, nine pure immature teratoma, and six endodermal sinus tumor with or without immature teratoma) were followed without chemotherapy after surgery. The 5-year overall survival rate was 95%, and the disease-free survival rate was 68%. Eight patients had a recurrence or developed a second primary germ cell tumor and required chemotherapy. All but one who died of a pulmonary embolus were salvaged with chemotherapy. In their second publication, 37 patients with stage Ia germ cell malignancies were followed with surveillance only after surgery. Twenty-two percent of dysgerminoma and 36% of nondysgerminoma patients had a recurrence. All but one of these patients were successfully salvaged and cured with cisplatin-based chemotherapy at the time of recurrence. The overall disease-specific survival rate was 94%. It is unlikely that randomized trials addressing the safety of this approach in ovarian germ cell tumors will be performed. Given the potential serious toxicity associated with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy, managing patients with stage 1 germ cell tumors of the ovary with surveillance is a reasonable option if they have been adequately staged.

Second-Look Laparotomy

The role of the second-look laparotomy (SLL) in germ cell tumors of the ovary is unclear. Williams, when reporting the experience of the GOG, noted that in patients with complete tumor resection followed by BEP chemotherapy, 43 of 45 patients had no evidence of tumor or mature teratoma only at the time of the SLL, suggesting that there is no value of SLL in patients with completely resected disease. There were 72 patients with advanced, incompletely resected tumors who received chemotherapy followed by SLL. Of 48 patients who did not have teratomatous lesions in their primary surgery, 45 had no tumor. The three patients who had persistent tumors died of their disease despite aggressive therapy. These authors think that the role of SLL is rarely, if ever, beneficial with an optimal cytoreduction followed by adequate chemotherapy. However, patients in this series who had incompletely resected tumors at initial surgery and had teratomatous elements present may benefit from SLL. There were 24 patients who had teratomatous elements in the primary tumor and 16 who had progressive or bulky mature elements at SLL. Four patients had residual immature teratoma. Fourteen of the 16 with residual teratoma and six of the seven with bulky disease remained tumor free after secondary cytoreduction. Therefore, the subgroup of patients that garner a survival benefit from SLL are those with incompletely resected disease with teratomatous elements at primary surgery. The use of advanced imaging technologies such as positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT) imaging may further reduce the impact of SLL. Preliminary studies suggest positive and negative predictive values of 100% and 96%, respectively, for PET imaging in seminomas looking for residual disease after chemotherapy, suggesting the possibility of similar results for germ cell malignancies.

Radiation Therapy

In the past, radiation therapy was traditionally used as adjuvant therapy for patients with germ cell malignancies and dysgerminomas in particular. Dysgerminomas are sensitive to radiation therapy with overall survival rates of between 70% and 100%. However, with the recent advances and success rates seen with combination chemotherapy, radiation therapy is rarely used today.

Chemotherapy

Current management strategies offer even patients with advanced malignancies an excellent chance at long-term control or cure. Because approximately 20% of patients with germ cell malignancies treated with surgery alone will be expected to recur, patients, except those with stage Ia dysgerminoma and stage Ia grade I immature teratoma, should be treated with adjuvant chemotherapy to reduce the risk of recurrent disease. VAC (vincristine, Adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide) was the first combination chemotherapy regimen widely used for treatment of these tumors. The GOG used VAC therapy to treat 76 patients with nondysgerminomatous germ cell tumors in the 1970s. Twenty-one percent of patients with stage I disease, 28% with completely resected disease, and 18% with immature teratomas failed VAC therapy, suggesting limited efficacy in these subgroups. However, 15 of 22 patients (68%) with advanced-stage or incompletely resected ovarian germ cell malignancies failed VAC therapy with a median progression-free survival (PFS) time of 8 months. VAC was also ineffective for approximately 50% of patients with endodermal sinus tumors (ESTs). Although the GOG subsequently treated 48 patients with stages I to III completely resected ESTs with VAC for six to nine courses. Thirty-five (73%) patients were free of disease with a median follow-up time of 4 years. Gershenson and associates also reported 18 of 26 (69%) patients with pure EST were free of tumors after VAC therapy. As a result of the success of cisplatin-based regimens in the treatment of testicular germ cell tumors, VAC was gradually replaced by VBP (vinblastine, bleomycin, and cisplatin). This transition resulted in an improvement in overall survival rate to 71%; however, failures still occurred even in patients with good prognosis at the conclusion of primary surgery. The GOG evaluated VBP in patients with stage III and IV or recurrent malignant germ cell tumors, many with measurable disease after surgery. Ninety-seven patients were treated, and this therapy produced a substantial number (43%) of durable complete responses. The overall progression-free interval at 24 months was approximately 51%.

In a landmark trial in testicular cancer in the 1980s, Williams et al. demonstrated improved survival and less neurotoxicity when etoposide was substituted for vinblastine. Subsequent smaller trials in ovarian germ cell tumors also demonstrated encouraging results. Williams reported the GOG experience with 93 patients who were given BEP as adjuvant treatment for malignant germ cell cancers of the ovary. Forty-two were immature teratomas, 25 were ESTs, and 24 were mixed germ cell tumors. At the time of Williams’ report, 91 of 93 patients had no evidence of disease after three courses of BEP with a median follow-up time of 39 months. One patient developed acute myelomonocytic leukemia 22 months after diagnosis, and a second patient developed lymphoma 69 months after treatment. Dimopoulos and colleagues reported a similar result from the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group. Forty patients with nondysgerminomatous tumors were treated with BEP or PVB. With a median follow-up time of 39 months, five patients developed progressive disease and died. Only one of the five who failed received BEP. Most recently, de La Motte Rouge and associates reported on 52 women with endodermal sinus tumor, 35 of whom had stage I or II tumors and 17 with stage III or IV disease. All were treated with BEP. After a median follow-up time of 68 months, the 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival rates were 94% and 90%, respectively. In this series, fertility-sparing surgery was performed in 41 cases, and pregnancy was achieved in 12 of 16 (75%) women who attempted to conceive, demonstrating that conservative surgery plus chemotherapy resulted in an appreciable number of successful pregnancies after treatment.

The combination of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) has become the standard of care for ovarian germ cell tumors ( Table 12.3 ). Treatment with BEP leads to cure in most women with malignant ovarian germ cell tumors and is well-tolerated. The BEP regimen consists of cisplatin 20 mg/m 2 and etoposide 100 mg/m 2 daily for 5 days and bleomycin 20 U/m 2 on day 1. The recommended treatment consists of three to four courses of BEP administered every 3 weeks in either inpatient or outpatient settings. Williams did demonstrate efficacy of carboplatin and etoposide in patients with stage IB to III dysgerminoma; none of the patients recurred after a median follow-up time of 7.62 years. However, contemporary data from studies with men with germ cell tumors showed cisplatin was superior to carboplatin, and the trial was closed early. Several investigators have also tried to determine if a 3-day BEP regimen is equally effective and decreases the occurrence of febrile neutropenia. Dimopoulos and colleagues demonstrated the safety and efficacy of outpatient BEP administered over 3 days using a lower dose of bleomycin in women with dysgerminoma or early-stage, optimally debulked nondysgerminoma malignancies. Likewise, the Taiwanese GOG investigated a 3-day BEP regimen. In this study, a regimen consisting of bleomycin (15mg/m 2 ; daily total dose <25 mg) and etoposide (100 mg/m 2 ) were administered on days 1 through 3, and cisplatin (100 mg/m 2 ) was administered on day 1 at 21-day intervals for 3 to 4 cycles. Among 239 patients, 159 had early-stage disease, and 53 had advanced-stage disease. When compared with early-stage disease, those with advanced disease had an approximately 20-fold increased risk of disease recurrence and a 19.2-fold increased risk of disease related mortality. Among patients with early-stage, optimally debulked tumors, the 3-day regimen did not adversely affect survival.

| Regimen | Dosage Schedule |

|---|---|

| VAC | |

| Vincristine, 1.5 mg/m 2 | Weekly IV administration for 12 wk (maximum dose 2.5 mg) |

| Dactinomycin, 0.5 mg | 5-day IV course every 4 wk |

| Cyclophosphamide, | 5-day IV course every 4 wk 5–7 mg/kg |

| VBP | |

| Vinblastine, 12 mg/m 2 | IV every 3 wk for four courses |

| Bleomycin, 20 U/m 2 | IV q wk for seven courses (maximum dose eighth course given in 30 U/m 2 ) wk 10 |

| Cisplatin, 20 mg/m 2 | Daily × 5 every 3 wk for three or four courses |

| BEP | |

| Bleomycin, 20 U/m 2 | IV q wk × 9 (maximum dose, 30 U) |

| Etoposide, 100 mg/m 2 | IV days 1–5 q 3 wk × 3 |

| Cisplatin, 20 mg/m 2 | IV days 1–5 q 3 wk × 3 |

Controversy exists regarding the efficacy of high-dose cisplatin used in combination with etoposide and bleomycin (HDBEP). Several adult trials in testicular germ cell malignancies have suggested improved efficacy compared with standard-dose cisplatin, but other studies have not seen this association. Cushing and colleagues, however, evaluated HDBEP in 74 pediatric patients with ovarian germ cell malignancies. The HDBEP regimen consisted of high-dose cisplatin at 200 mg/m 2 /d for 5 days with etoposide, 100 mg/m 2 /d for 5 days, and bleomycin, 15 mg/m 2 /d for 1 day per cycle. This study found no difference in overall survival and increased toxicity with the HDBEP regimen. These studies have not been replicated in adults with ovarian germ cell malignancies. Currently, there is no established role of high-dose therapy in ovarian germ cell tumors.

Current management strategies for germ cell malignancies use chemotherapy in an adjuvant setting and to treat recurrent disease. Completely resected disease treated in this fashion can be cured nearly 100% of the time. Metastatic or incompletely resected tumors, however, may fare worse but still have excellent long-term survival rates and should be treated aggressively with adjuvant chemotherapy.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Because the majority of patients with malignant ovarian germ cell tumors are diagnosed when the disease is in an early stage, most patients are treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy. In patients with widespread disease, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) may be warranted. Few trials, and certainly no randomized trials, are available to answer the question regarding utility in these patients. However, Talukdar et al. evaluated the use of NACT using four cycles of BEP followed by fertility-sparing surgery in 23 patients with bulky disease compared with 43 patients who underwent primary debulking surgery with FIGO stage III or IV disease during the same time period. The WHO criteria for response to chemotherapy were used, with a complete response defined as the complete disappearance of all clinically detectable disease and normalization of tumor markers. A partial response was defined as 50% or greater reduction in tumor size and decrease in tumor markers. After NACT, 21 patients showed a response to treatment with 16 achieving a complete response and five with a partial response. Eighteen of 21 patients in the NACT group were then able to undergo fertility-sparing surgery, and those with residual disease were given an additional two cycles of BEP. Of the evaluable patients, 21 of 23 patients survived with a median disease-free survival period of 211 months. Lu et al. also investigated the role of neoadjuvant treatment in a group of 127 women with yolk sac tumors. After a median follow-up period of 46 months, there was no significant difference in recurrence rate between the NACT and primary debulking group. For women presenting with advanced, bulky disease, or medical comorbidities, initial studies suggest a role for NACT.

Recurrences in Germ Cell Cancer

Even in cases of advanced-stage disease, the majority of patients with germ cell malignancies are cured with a combination of primary surgery and adjuvant combination platinum-based chemotherapy. All patients with germ cell malignancies, especially those with early-stage disease treated with conservative therapy for curative intent, warrant close follow-up. Patients with early-stage dysgerminoma treated with salpingo-oophorectomy alone, for example, have disease recurrence in 15% to 25% of cases. Studies evaluating surveillance strategies for ovarian germ cell tumors and SCSTs have not been performed; therefore, recommendations are based on expert opinion. Patients should be seen every 2 to 4 months for the first 2 years after treatment at which point they can transition to annual visits. Surveillance should include a thorough physical examination and serum tumor markers. Radiologic scans should be reserved for elevations in tumor markers or concerning physical exam findings or symptoms, but for patients without elevated tumor markers, imaging within the first 2 years may be helpful.

Recurrences usually occur within 2 years of primary therapy and can be treated successfully. The value of secondary cytoreductive procedures in patients with germ cell malignancies has not been studied. Given the sensitivity of these malignancies to combination chemotherapy regimens, it is highly likely that metastatic lesions will respond to subsequent chemotherapy, limiting the value of secondary cytoreduction. Yet cytoreduction remains an effective management option for isolated lesions. The optimal chemotherapy regimen in recurrent disease is unknown. Historically, studies have included both patients with advanced primary disease and recurrent disease in the same trial. The recurrent cohorts in these trial are often very small, less than 10 patients, limiting significant conclusions about therapy. Recurrences after chemotherapy are defined as platinum resistant or platinum sensitive, a classification with clinical significance because platinum-resistant disease is not thought to be curable. For patients with platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory disease, optimal treatment has not been defined, and the prognosis overall is poor. The group at the MD Anderson Cancer Center noted 42 primary therapy failures in 160 patients with germ cell tumors. Vincristine, actinomycin-D, and cyclophosphamide were the principal agents used during the first 10 years of the study period. Cisplatin-based combination therapy was used more extensively in the late 1970s and 1980s. Salvage therapy varied with 24 patients receiving surgery and 34 patients receiving chemotherapy. Of patients receiving chemotherapy, 11 were treated with VAC and 11 with a platinum-based regimen. The median survival time for the entire group was 19 months. The PFS time was 6.8 months with a range of 0.9 to 24 months. No patient had disease recurrence longer than 2 years from initial diagnosis. More recently, male patients with platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory germ cell tumors have been treated with combination chemotherapy consisting of gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and paclitaxel. This regimen has an acceptable toxicity profile, a 51% overall response rate, and a 39% complete or tumor marker–negative response rate. The median response duration was 8 months.

Treatment Toxicity

Given the favorable long-term outcomes associated with modern surgical management and combination platinum-based chemotherapy, the long-term effects of treatment must be considered carefully. Because many patients undergo conservative surgery for their disease, meticulous surgical technique is essential to avoid future infertility related to surgically induced pelvic adhesive disease. Equally important is avoiding unnecessary hysterectomies and biopsies of normal-appearing contralateral ovaries. Women with fertility-sparing surgery can be expected to have the same survival outcome as those patients treated with standard surgery. A review of SEER data from 1988 to 2001 involving 760 patients with germ cell malignancies concluded that the overall survival rate of patients treated with fertility-sparing surgery ( n = 313) was not statistically different from those who underwent standard surgery. This study revealed that the use of fertility-sparing surgery also had increased over the study period. Two-thirds of the patients had stage I to II disease, and one third had stage III to IV disease. The most common histologic subtype was immature teratoma (55%) followed by dysgerminoma (32%).

Although successful, concern exists over potential toxicity of the BEP regimen. Namely, bleomycin is associated with acute and long-term pulmonary toxicity, etoposide with the risk of secondary malignancies, and cisplatin with nephrotoxicity. Controversy exists over whether baseline pulmonary function testing is required before initiating bleomycin. Data from retrospective trials and testicular cancer literature suggest carboplatin and etoposide is an acceptable regimen for patients who cannot tolerate BEP.

The long-term effect of combination chemotherapy in germ cell malignancies is less clear. Of particular concern is the risk of development of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) associated with etoposide use. This risk appears to be dose and schedule dependent. AML rarely develops in patients receiving three cycles or less of etoposide or cumulative doses of less than 2000 mg/m 2 . It is estimated that the risk of developing AML is 0.4% if these cutoff values are used. Leukemia, when it occurs, typically is seen within 2 to 3 years after treatment. An analysis of the risk-to-benefit ratio favors the use of etoposide in advanced germ cell malignancies, in which one case of etoposide-induced AML would be expected to occur for every 20 patients cured.

The long-term effects of chemotherapy on gonadal function appear to be minimal. Most younger patients can expect a return to normal ovarian function and reproductive potential with no additional risk of congenital malformations in their offspring. The most significant risk factor for impaired fertility is age and type of treatment administered. Although ovarian failure is a risk associated with chemotherapy, factors such as older age at treatment, higher drug doses, and long duration of therapy appear to confer higher risk. Childhood cancer patients treated with standard contemporary agents such as BEP have the greatest likelihood of preservation of fertility, resumption of normal menstrual cycles, and normal sexual development by virtue of the higher number of follicles present in young women compared with older women. Although normal menstrual cycles will likely resume in reproductive-age women, data suggest an increased risk of diminished ovarian reserve resulting in a significant reduction in the probability of pregnancy by 50%. Reproductive-aged women are likely to have reduced ovarian volume compared with control participants, fewer antral follicles on ultrasonography, and lower levels of inhibin B and estradiol on cycle days 2 to 5. Alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide are far more likely to cause toxicity to the gonads than other chemotherapeutic agents. In one study, alkylating agents had an odds ratio (OR) of 4 for causing premature ovarian failure compared with platinum agents (OR, 1.8) or plant alkaloids (OR 1.2).

There is some literature to suggest that gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists may be cytoprotective for primordial follicles when given during chemotherapy. Most of these data are retrospective; however, recently, Badawy and colleagues reported on a prospective randomized trial in 80 breast cancer patients younger than age 40 years who were randomly assigned to GnRH agonists with chemotherapy or chemotherapy alone. Ninety percent of study patients resumed menses, and 70% resumed spontaneous ovulation within 8 months of completing therapy compared with 33% and 26% of control patients, respectively. In the setting of germ cell malignancies, in which younger age at diagnosis is the norm, these patients should be counseled on the risks and benefits of GnRH agonists as well as consultation with a reproductive endocrinologist.

Dysgerminoma

Dysgerminoma is the most common germ cell malignancy, accounting for 1% to 2% of primary ovarian neoplasms and for 3% to 5% of ovarian malignancies. Dysgerminoma may occur at any age from infancy to old age, but most cases occur in adolescence and early adulthood ( Fig. 12.3 ). They also present at a relatively early stage:

| Stage Ia | 65%–75% |

| Stage Ib | 10%–15% |

| Stages II and III | 15% |

| Stage IV | 5% |

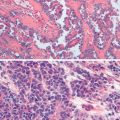

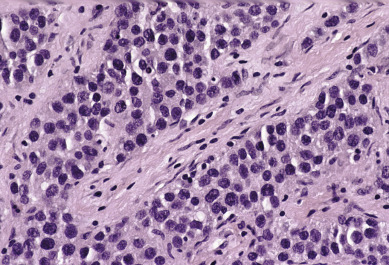

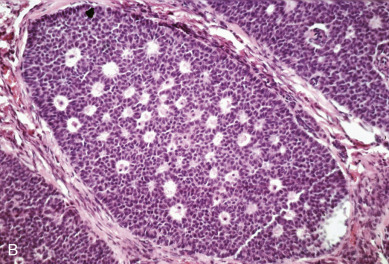

Dysgerminoma consists of germ cells that have not differentiated to form embryonic or extraembryonic structures ( Fig. 12.4 ). The stroma is almost always infiltrated with lymphocytes and often contains granulomas similar to those seen in sarcoidosis. Occasionally, dysgerminoma contains isolated gonadotropin-producing syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells. An elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase or hCG level may be present in these patients. Grossly, the tumor may be firm, fleshy, cream colored, or pale tan; both its external and cut surfaces may be lobulated. A few dysgerminomas arise in females with sex chromosome abnormalities, particularly those with pure (46,XY) or mixed (45,X, 46,XY) gonadal dysgenesis or testicular feminization (46,XY). In such cases, the dysgerminoma often develops in a previously existing gonadoblastoma. The symptoms of dysgerminoma are similar to those observed in patients with other solid ovarian neoplasms. Large, rapidly growing tumors may lead to a relatively short duration of symptoms. The most common initial symptoms are abdominal enlargement and the presence of a mass in the lower abdomen. When the tumor is small and moves freely, its capsule is intact. Large lesions, however, may rupture or adhere to surrounding structures. Rupture can lead to peritoneal implantation, resulting in an increase in stage. Occasionally, menstrual and endocrine abnormalities may be the initial symptoms, but these symptoms tend to be more common in patients with dysgerminoma combined with other neoplastic germ cell elements, especially choriocarcinoma. In several cases, the tumor has been found incidentally at cesarean section or as a cause of dystocia. Dysgerminoma is the most common malignant ovarian neoplasm observed in pregnancy. The relatively common finding of dysgerminoma in pregnant patients is nonspecific and relates to the age of the patient rather than to the pregnant state. Dysgerminoma is the only germ cell tumor in which the opposite ovary is frequently involved with the tumor process (10%–20% of cases). Kurman and Norris reported a 20% incidence of disease in the serially sectioned normal appearing opposite ovary. Dysgerminomas are notable by their predilection for lymphatic spread and their sensitivity to irradiation and chemotherapy. The lymph nodes in the vicinity of the common iliac arteries and the terminal part of the abdominal aorta are typically the first to be affected. Occasionally, there may be marked enlargement of these lymph nodes, with a mass evident on abdominal examination. The lesion can spread from these abdominal nodes to the mediastinal and supraclavicular nodes. Hematogenous spread to other organs occurs later. Any organ can be affected, although involvement of the liver, lungs, and bones is most common.

Because 85% of all patients with dysgerminomas are younger than 30 years, conservative therapy and preservation of fertility are major considerations. In patients in whom unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is performed, careful inspection of the contralateral ovary and exploration to rule out disseminated disease are mandatory. The authors’ routine is not to wedge or bivalve the opposite ovary if it has a normal size, shape, and consistency. In a review of the literature, more than 400 cases of dysgerminoma were reported. Seventy percent of patients had stage I disease at diagnosis, and only 10% involved both ovaries. Schwartz and colleagues reported four patients with metastasis to the contralateral ovary and preservation of that ovary with subsequent chemotherapy. All patients were alive and had no disease 14 to 56 months after diagnosis. Assessment of the retroperitoneal lymph nodes is an important part of the initial surgical therapy because these neoplasms tend to spread to the lymph nodes, particularly to the high para-aortic nodes.

Conservative surgery without radiation or adjuvant chemotherapy in stage Ia lesions has resulted in excellent outcomes ( Table 12.4 ). Several prognostic factors in dysgerminoma influence the decision to use adjuvant chemotherapy in early stages of the disease. Some authors suggest that in patients with large tumors (>10 cm), there is a greater chance of a recurrence; therefore, adjuvant therapy should be given. Today, most agree that tumor size is not prognostically important, and these patients do not require additional therapy. Although there is presently no good evidence that the behavior of an individual tumor can be assessed from its histologic appearance, we do know that the presence of other germ cell elements worsens prognosis. Data regarding the prognostic significance of age is inconsistent. The long-term survival rate is almost 90% across all patients who have stage I lesions.

| 10-Year Survival Rate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conservative Surgery (%) | Nonconservative Therapy * (%) | |

| Asadourian and Taylor | 42/46 (91) † | 21/25 (84) |

| Gordon et al. | 68/72 (94) † | 11/14 (79) |

| Malkasian and Symmonds | 23/27 (85) † | 13/14 (93) |

| Total | 133/145 (92) † | 45/53 (85) |

† Includes those salvaged after a recurrence (23 or 25%–92%).

De Palo and associates reported on 56 patients who had pure dysgerminomas. In their study, 44 patients underwent lymphangiography, and a positive study resulted in the restaging of 32% of patients. Diaphragmatic implants were not found in any patients, and positive cytologic findings were obtained in only three patients. The 5-year relapse-free survival rates were 91% in patients with stages Ia, Ib, and Ic; 74% in those with stage III retroperitoneal disease; and 24% in patients who had stage III peritoneal disease. Peritoneal involvement of any kind was associated with a poor prognosis if disease had extended to the abdominal cavity. All patients with stage III disease received postoperative radiation therapy.

These patients should be followed closely and have periodic examinations because approximately 90% of recurrences appear in the first 2 years after initial therapy. Fortunately, most recurrences can be successfully eradicated by salvage therapy including surgery, chemotherapy, and potentially radiation therapy. Recurrences should be treated aggressively with reexploration and cytoreductive surgery. The removed tissue should be examined carefully for evidence of germ cell elements other than dysgerminoma. Some presumed recurrent dysgerminomas have been found to be mixed germ cell tumors and should be treated accordingly.

Although radiation therapy has been successful in treating dysgerminomas, chemotherapy has become the treatment of choice because radiotherapy is associated with a high incidence of gonadal failure. The success rate of chemotherapy is as good as that of radiation, and preservation of fertility is possible in many patients, even those with bilateral ovarian disease. Weinblatt and Ortega reported on five children with extensive disease who were treated with chemotherapy as the primary therapeutic modality. Three of the five children were alive and free of disease at the time of the report, suggesting a therapeutic approach to extensive childhood dysgerminoma that spares pelvic and reproductive organs.

The common association of dysgerminoma with gonadoblastoma, a tumor that almost always occurs in patients with dysgenetic gonads, indicates that there is a relationship between dysgerminoma and genetic and somatosexual abnormalities. Patients with these genetic abnormalities should be offered gonadectomy after puberty to prevent the development of gonadoblastoma or dysgerminoma. Phenotypically normal females suspected of having a dysgerminoma should be evaluated with a karyotype, especially if ovarian conservation is desired. Patients with pathology reports that reveal streak gonads or gonadoblastomas should also be karyotyped. If a Y chromosome is present, the retained contralateral ovary should be removed to prevent neoplasia. Historically, fertility-sparing surgery has not been offered to patients with dysgerminoma associated with gonadoblastoma because of the frequent occurrence of bilateral tumors and the absence of normal gonadal function. Investigation of the genotypes and karyotypes of all patients with this neoplasm is recommended by some, especially if any history of virilization or other developmental abnormalities is elicited. In vitro fertilization can be used in patients without gonads. Therefore, it may be prudent to preserve the uterus in patients in whom the ovaries must be removed. In most cases, the authors leave the uterus. This is particularly important in prepubertal patients because in these patients, other signs of abnormal function (eg, primary amenorrhea, virilization, and absence of normal sexual development) are lacking.

Often lesions that consist primarily of dysgerminoma elements contain small areas of more malignant histology (eg, embryonal carcinoma or endodermal sinus tumor). If tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) or hCG are elevated, a strong suspicion of mixed lesions should be entertained. When the dysgerminoma is not pure and these more malignant components are present, the prognosis and therapy are determined by the more malignant germ cell elements, and the dysgerminoma component is disregarded.

Endodermal Sinus Tumor (Yolk Sac Tumor)

Endodermal sinus tumors are the second most common form of malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary, accounting for 22% of malignant germ cell lesions in one large series. The median age at diagnosis is 19 years old, and three-fourths of thepatients are initially seen with a combination of abdominal pain and abdominal or pelvic mass. Endodermal sinus tumors are characterized by extremely rapid growth and extensive intraabdominal spread; almost half the patients seen by a physician complain of symptoms of 1 week’s duration or less.

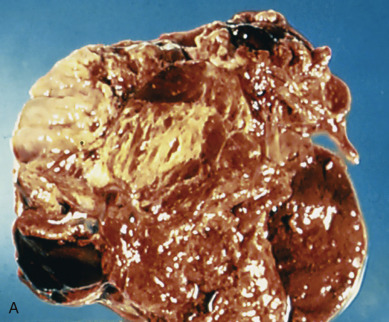

Acute symptoms can alternatively be caused by torsion of the tumor and may lead to the diagnosis of acute appendicitis or a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. These yolk sac tumors are almost always unilateral. The tumor is usually large with most tumors measuring between 10 and 30 cm. On the cut surface, they appear gray-yellow with areas of hemorrhage and cystic, gelatinous changes. These neoplasms are highly malignant; they metastasize early and invade the surrounding structures. Intraabdominal spread leads to extensive involvement of abdominal structures with tumor deposits. Metastases also occur via the lymphatic system. AFP levels are often elevated.

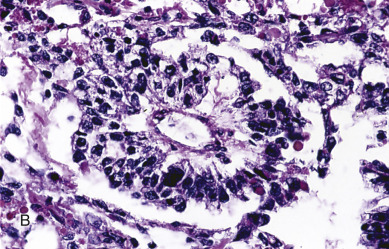

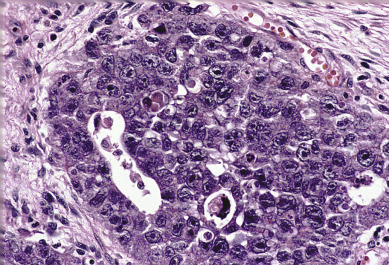

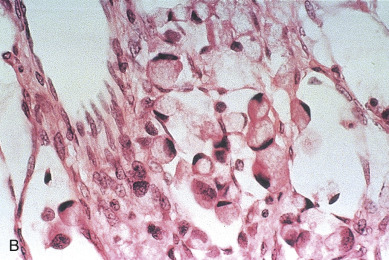

Endodermal sinus tumors are thought to originate from germ cells that differentiate into the extra embryonal yolk sac because the tumor structure is similar to that found in the endodermal sinuses of the rat yolk sac. The tumors consist of scattered tubules or spaces lined by single layers of flattened cuboidal cells; loose reticular stroma; numerous scattered para-aminosalicylic–positive globules; and, within some spaces or clefts, a characteristic invaginated papillary structure with a central blood vessel (Schiller-Duval body) ( Fig. 12.5 ). Frequently, intracellular and extracellular hyaline droplets that represent deposits of AFP can be identified throughout the tumor.

Historically, the prognosis for patients with endodermal sinus tumor of the ovary was unfavorable. Most patients died of the disease within 12 to 18 months of diagnosis. Until multiple-agent chemotherapy was developed, there were only a few known 5-year survivors, most of whom had tumors confined to the ovary. Kurman and Norris reported no long-term survivors in 17 patients with stage I tumors who were receiving adjunctive radiation or single alkylating agent, dactinomycin, or methotrexate. Gallion and colleagues reviewed the literature in 1979 and found that only 27% of 96 patients with stage I endodermal sinus tumors were alive at 2 years. The tumor is not sensitive to radiation therapy, although there may be an initial response. Optimal surgical extirpation of the disease has been advocated, but this alone is unsuccessful in producing a significant number of cures.

With surgery and multiagent chemotherapy, however, there have been optimistic reports of sustained remissions. In several cases, the tumor consisted of endodermal sinus tumors admixed with other neoplastic germ cell elements, frequently dysgerminoma. The clinical course in most patients with tumors composed of endodermal sinus tumor associated with dysgerminoma or other neoplastic germ cell elements does not differ greatly from that in patients with pure endodermal sinus tumors. Mixed germ cell lesions often contain endodermal sinus tumors as one of the types present.

From a practical point of view, serum AFP determination is considered to be a useful diagnostic tool in patients who have endodermal sinus tumors and should be considered an ideal tumor marker. It can be useful when monitoring the results of therapy and for detecting metastasis and recurrences after therapy. As noted earlier, many investigators use AFP as a guide to the number of courses needed for an individual patient. In many cases, only three or four courses have placed patients into remission with long-term survival. Levels of hCG and its beta subunit (beta-hCG) have been found to be normal in patients with endodermal sinus tumor.

Embryonal Carcinoma

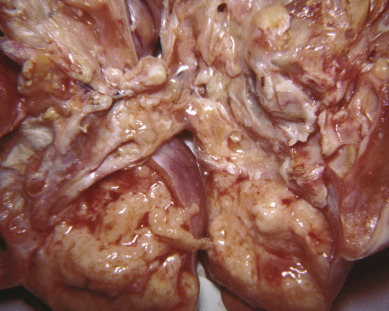

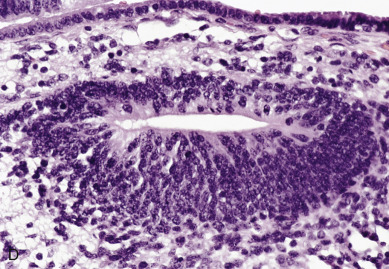

Embryonal carcinoma is one of the most aggressive ovarian malignancies ( Fig. 12.6 ). The neoplasm closely resembles the embryonal carcinoma of the adult testes, a relatively common tumor. However, it represents only 4% of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors in the ovary, and its confusion with choriocarcinoma and ESTs in the past accounts for its late identification as a distinct entity. It usually manifests as an abdominal mass or pelvic mass occurring at a mean age of 15 years. More than half of the patients have hormonal abnormalities, including precocious puberty, irregular uterine bleeding, amenorrhea, or hirsutism. The tumors consist of large primitive cells with occasional papillary or glandlike formations ( Fig. 12.7 ). The cells have eosinophilic cytoplasms with distinct borders and round nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Numerous mitotic figures, many atypical, are seen; scattered throughout the tumor are multinucleated giant cells that resemble syncytial cells.

These tumors secrete hCG from syncytiotrophoblast-like cells and AFP from large primitive cells, and these tumor markers can be used to monitor progress during therapy. This tumor probably arises from primordial germ cells, but it develops before there is much further differentiation toward either embryonic or extraembryonic tissue. In a review of 15 patients, Kurman and Norris reported an actuarial survival rate of 30% for the entire group; for those with stage I tumors, the survival rate was 50% ( Table 12.5 ). This result is significantly better than the survival rate for endodermal sinus tumors for the same period of time and before the advent of multiple-agent adjuvant chemotherapy.

| Endodermal Sinus Tumor ( n = 71) | Embryonal Carcinoma ( n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (yr) | 19 | 15 |

| Prepubertal status (%) | 23 | 47 |

| Precocious puberty (%) | 0 | 43 |

| Positive pregnancy test | None (0/15) | All (9/9) |

| Vaginal bleeding (%) | 1 | 33 |

| Amenorrhea (%) | 0 | 7 |

| Hirsutism (%) | 0 | 7 |

| Survival, stage I patients (%) | 16 | 50 |

| Human chorionic gonadotropin | Negative (0/15) | Positive (10/10) |

| α-Fetoprotein | Positive (15/15) | Positive (7/10) |

Polyembryoma

Polyembryoma is a rare ovarian germ cell neoplasm that consists of numerous embryoid bodies resembling morphologically normal embryos. Similar homologous neoplasms occur more frequently in the human testes. To date, only a few ovarian polyembryomas have been reported. In most cases, the polyembryoma has been associated with other neoplastic germ cell elements, mainly the immature teratoma. Polyembryoma is a highly malignant germ cell neoplasm. It is usually associated with invasion of adjacent structures and organs and metastases confined to the abdominal cavity. The tumor is not sensitive to radiotherapy, and its response to chemotherapy is unknown.

Choriocarcinoma

Choriocarcinoma, is a rare, highly malignant tumor that may be associated with sexual precocity. Gestational choriocarcinomas of the ovary contain paternal DNA and are further classified into primary gestational choriocarcinoma associated with ovarian pregnancy or metastatic choriocarcinoma arising in other parts of the genital tract, mainly the uterus. Nongestational choriocarcinomas are germ cell tumors that differentiate toward trophoblastic structures. Only nongestational choriocarcinoma of the ovary is discussed here. In most cases, the tumor is admixed with other neoplastic germ cell elements, and their presence is diagnostic of nongestational choriocarcinoma. The tumor, in common with other malignant germ cell neoplasms, occurs in children and young adults. Its occurrence in children has been emphasized; in some series, 50% of cases occurred in prepubescent children. This high incidence in children may result from the previous reluctance of investigators to make the diagnosis in adults.

Choriocarcinomas secrete hCG , leading to manifestations of isosexual precocious puberty with mammary development, growth of pubic and axillary hair, and uterine bleeding. In adult patients, the increased production of hCG may cause signs of ectopic pregnancy. Estimation of urinary or plasma hCG levels is a useful diagnostic test in these cases. Historically, the prognosis of patients with choriocarcinoma of the ovary was unfavorable, but modern chemotherapy regimens have effectively improved survival.

Mixed Germ Cell Tumors

Mixed germ cell tumors contain at least two malignant germ cell elements. Dysgerminoma is the most common component, 80% in Kurman and Norris’ report and 69% in material from the MD Anderson Hospital. Immature teratoma and EST are also frequently identified; embryonal carcinoma and choriocarcinoma are seen only occasionally. It is not unusual to see three or four different germ cell components. In 42 patients treated at the MD Anderson Hospital from 1944 through 1983, nine patients were treated with surgery alone, and another six patients received radiation therapy; all developed recurrences. To improve outcomes, the most malignant cell type should drive the selection of the adjuvant chemotherapy regimen.

Teratoma

Mature Cystic Teratoma

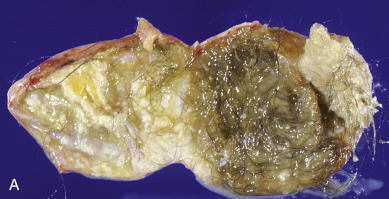

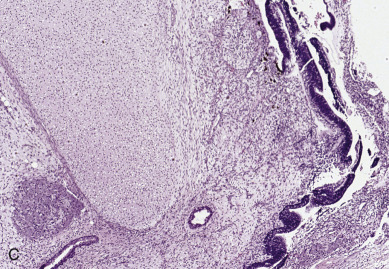

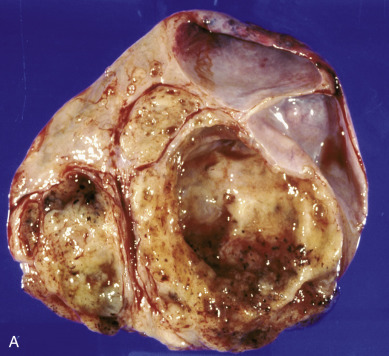

Accounting for more than 95% of all ovarian teratomas, the dermoid cyst, or mature cystic teratoma, is one of the most common ovarian neoplasms. Teratomas account for approximately 15% of all ovarian tumors. They are the most common ovarian tumors in women in the second and third decades of life. Most benign cystic lesions contain mature tissue of ectodermal, mesodermal, or endodermal origin. The most common elements are ectodermal derivatives such as skin, hair follicles, and sebaceous or sweat glands, accounting for the characteristic histologic and gross appearance of teratomas ( Fig. 12.8 ). These tumors are usually multicystic and contain hair intermixed with foul-smelling, sticky, keratinous and sebaceous debris. Occasionally, well-formed teeth are seen along with cartilage or bone. If the tumor consists of only ectodermal derivatives of skin and skin appendages, it is a true dermoid cyst. A mixture of other, usually mature tissues (gastrointestinal, respiratory) may be present.

The clinical manifestation of this slow-growing lesion is usually related to its size, compression, or torsion or to a chemical peritonitis secondary to intraabdominal spill of the cholesterol-laden debris. The latter event tends to occur more commonly when the tumor is large. Torsion is the most frequent complication, observed in as many as 16% of the cases in one large series, and tends to occur more commonly during pregnancy, the puerperium, and in children and younger patients. Severe acute abdominal pain is usually the initial symptom, and the condition is considered to be an acute abdominal emergency. Mature cystic teratomas are said to comprise 22% to 40% of ovarian tumors in pregnancy, and 0.8% to 12.8% of reported cases of mature cystic teratomas have occurred in pregnancy. Rupture of a mature cystic teratoma is an uncommon complication, occurring in approximately 1% of cases, but it is much more common during pregnancy and may manifest during labor. The immediate result of rupture may be shock or hemorrhage, especially during pregnancy or labor, but the prognosis even in these cases is favorable. Rupture of the tumor into the peritoneal cavity may be followed by a chemical peritonitis caused by the spill of the contents of the tumor. This may result in a marked granulomatous reaction, leading to the formation of dense adhesions throughout the peritoneal cavity. Infection is an uncommon complication of mature cystic teratoma and occurs in approximately 1% of cases. The infecting organism is usually a coliform, but Salmonella spp. infection causing typhoid fever has also been reported. Removal of the neoplasm by ovarian cystectomy or, rarely, oophorectomy is adequate therapy. Malignant degeneration of mature teratomas is a rare occurrence. When it occurs, the most common secondary tumor is a squamous cell carcinoma. The prognosis and behavior of this secondary malignancy are similar to those of squamous cell cancers arising in other anatomic sites and appear to be highly dependent on stage. There is no consensus on treatment recommendations; however, patients with stage I to II disease treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and whole-pelvic radiation have a chance for long-term survival. Although squamous cell carcinoma in this setting is usually an incidental finding at pathology, preoperative risk factors include age older than 50 years, tumor size greater than 10 cm, and elevated concentrations of squamous cell carcinoma antigen and carcinoma antigen 125 (CA-125).

Mature Solid Teratoma

Mature solid teratoma is a rare ovarian neoplasm and a very uncommon type of ovarian teratoma. The histologic components in a mature solid teratoma are similar to those found in an immature solid teratoma, which occurs mainly in children and young adults. The presence of immature elements immediately excludes the tumor from this group; by definition, only tumors composed entirely of mature tissues may be included. The tumor is usually unilateral and is adequately treated by unilateral oophorectomy. Although this neoplasm is considered benign, mature solid teratomas may be associated occasionally with peritoneal implants that consist entirely of mature glial tissue. Despite the extensive involvement that may be present, the prognosis is excellent.

Immature Teratoma

Immature teratomas consist of tissue derived from the three germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—and, in contrast to the much more common mature teratoma, they contain immature or embryonal structures. These tumors have had a variety of names, including solid teratoma, malignant teratoma, teratoblastoma, teratocarcinoma, and embryonal teratoma. These names arose because immature teratomas have been incorrectly considered mixed germ cell tumors or secondary malignant tumors originating in mature benign teratomas. Mature tissues are frequently present and sometimes may predominate. Immature teratoma of the ovary is an uncommon tumor, comprising less than 1% of ovarian teratomas. In contrast to the mature cystic teratoma, which is encountered most frequently during the reproductive years but occurs at all ages, the immature teratoma occurs most commonly in the first 2 decades of life and is almost unknown after menopause. By definition, an immature teratoma contains immature neural elements. According to Norris and associates, the quantity of immature neural tissue alone determines the grade. Neuroblastoma elements, glial tissue, and immature cerebellar and cortical tissue may also be seen. These tumors are graded histologically on the basis of the amount and degree of cellular immaturity. The range is from grade I (mature teratoma containing only rare immature foci) through grade III (large portions of the tumor consist of embryonal tissue with atypia and mitotic activity). Generally, older patients tend to have lower grade primary tumors compared with younger patients. When the neoplasm is solid and all elements are well differentiated histologically (solid mature teratoma), a grade 0 designation is given ( Table 12.6 ).

| Grade | Thurlbeck and Scully | Norris et al. |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | All cells well differentiated | All tissue mature; rare mitotic activity |

| 1 | Cells well differentiated; rare small foci of embryonal tissue | Some immaturity and neuroepithelium limited to low-magnification field in any slide (×40) |

| 2 | Moderate quantities of embryonal tissue; atypia and mitosis present | Immaturity and neuroepithelium does not exceed three low-power microscopic fields in any one slide |

| 3 | Large quantities of embryonal tissue; atypia and mitosis present | Immaturity and neuroepithelium occupying four or more low magnification fields on a single slide |

Immature teratomas are almost never bilateral, although occasionally a benign teratoma is found in the opposite ovary. These tumors may have multiple peritoneal implants at the time of initial surgery, and the prognosis is closely correlated with the histologic grade of the primary tumor and the implants. Norris and coworkers studied 58 patients with immature teratomas and reported an 82% survival rate for patients who had grade I primary lesions, 63% for grade II, and 30% for grade III ( Table 12.7 ). These results antedate the use of multiple-agent chemotherapy.

| Grade | Patients ( n ) | Tumor Deaths (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | 4 (18) |

| 2 | 24 | 9 (37) |

| 3 | 10 | 7 (70) |

Multiple sections of the primary lesion and wide sampling of the peritoneal implants are necessary to properly grade the tumor. In most cases, the implants are better differentiated than the primary tumors. Both the primary lesion and the implants should be graded according to the most immature tissue present. Patients with mature glial implants have an excellent prognosis; those with immature implants, however, do not.

To date, the histologic grade and fertility desires of the patient have been the determining factors regarding extent of surgical therapy and subsequent adjuvant therapy. Because the lesion is rarely bilateral in its ovarian involvement, the present method of therapy consists of unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with wide sampling of peritoneal implants. Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy does not seem to be indicated because it does not influence the outcome for the patient. Although some authors have advocated cystectomy alone for early-stage, low-grade disease, this management strategy should be approached with caution. Radiotherapy has also been shown to have little value. If the primary tumor is grade I and all peritoneal implants are grade 0, no further therapy is recommended. However, if the primary tumor is grade II or III or if implants or recurrences are grade I, II, or III, triple-agent chemotherapy is frequently recommended. The recommendation to use adjuvant chemotherapy in high-grade stage I disease is based on studies performed before meticulous surgical staging of germ cell malignancies was routine. Cushing and colleagues evaluated surgical therapy alone in 44 pediatric and adolescent patients younger than the age of 15 years who had completely resected immature teratomas of all grades. Thirty-one patients had pure immature teratomas, and 13 patients had immature teratomas with microscopic endodermal sinus tumor foci. The 4-year event-free and overall survival rates for both groups were 97% and 100%, respectively. The authors concluded that surgery alone was curative for most children and adolescents with completely resected ovarian immature teratomas of any grade and advocated avoiding adjuvant chemotherapy in this group.

In previous trials including SLL, these patients were free of immature elements but retained peritoneal implants containing exclusively mature elements. This was labeled chemotherapeutic retroconversion of immature teratoma of the ovary and is a similar if not identical syndrome as the “growing teratoma syndrome” described in testicular nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. All of these patients had uneventful follow-ups with the mature implants apparently remaining in static states. Growing teratoma syndrome (GTS) is characterized by the persistence or development of an enlarging mass during or after adjuvant chemotherapy. Normalization of tumor markers is also seen, and on pathologic analysis, only mature teratoma is noted in the specimen. Treatment of this syndrome is challenging, but surgery is diagnostic and is also the mainstay of therapy. Few cases of GTS are reported in the literature; thus, many current strategies are taken from reports of GTS after testicular nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Byrd et al. reported on five cases of GTS in women undergoing treatment of early and advanced stage ovarian germ cell tumors. All women received BEP after surgery. GTS occurred 1 to 6 months after completion of chemotherapy in women with advanced disease and at 1 and 11 years in the two women with stage I disease. All patients in this cohort required extensive surgery but remain alive and well with no evidence of disease at last follow-up. For patients with this syndrome, maximal cytoreductive efforts should be undertaken because they offer optimal diagnostic and therapeutic benefit.

Monodermal or Highly Specialized Teratomas

Struma ovarii.

Another tumor thought to represent the unilateral development of benign teratoma is struma ovarii, which consists totally or predominantly of thyroid parenchyma. This is an uncommon lesion and should not be confused with benign teratomas, which contain small foci of thyroid tissue. Between 25% and 35% of patients with strumal tumors will have clinical hyperthyroidism. The gross and microscopic appearances of these lesions are similar to those of typical thyroid tissue, although the histologic pattern may resemble that in adenomatous thyroid. These ovarian tumors may undergo malignant transformation, but they are usually benign and easily treated by simple surgical resection.

Carcinoid tumors.

Primary ovarian carcinoid tumors usually arise in association with gastrointestinal or respiratory epithelium, which is present in mature cystic teratoma. They may also be observed within a solid teratoma or a mucinous tumor, or they may occur in an apparently pure form. Primary ovarian carcinoid tumors are uncommon; approximately 50 cases have been reported. The age distribution of patients with ovarian carcinoid tumors is similar to that of patients with mature cystic teratoma, although the average age may be slightly higher in ovarian carcinoid tumors. Many patients are postmenopausal.

One-third of the reported cases have been associated with the typical carcinoid syndrome despite the absence of metastasis. This is in contrast to intestinal carcinoid tumors, which are associated with the syndrome only when there is metastatic spread to the liver. Excision of the tumor has been associated with the rapid remission of symptoms in all of the described cases and the disappearance of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid from the urine. The primary ovarian carcinoids are only occasionally associated with metastasis; metastasis was observed in only 3 of 47 reported cases in one review. The prognosis after excision of the primary tumor is favorable, and in most cases, a cure results.

Strumal carcinoid is an even rarer entity and represents a close admixture of the previously discussed struma ovarii and carcinoid tumors. Strumal carcinoids may actually represent medullary carcinoma, resulting in thyroid tissue. Most cases follow a benign course.

Tumors of Germ Cell and Sex Cord Derivation

Tumors of germ cell and sex cord derivation are unique, rare tumors that are composed of two distinct populations of cells closely admixed but with different origins. The two histologic types of tumors that fall into this category are gonadoblastomas and mixed germ cell–SCSTs. Gonadoblastomas are benign tumors of the ovary that occur in dysgenetic gonads and are frequently associated with the development of a malignant germ cell component. The risk of developing a malignant germ cell component increases with age, such that prepubertal girls at the time of gonadectomy are very unlikely to have an associated malignant germ cell tumor, but the risk of malignancy approaches 100% for women in their 20s. Mixed germ cell–SCTSs occur in chromosomally normal gonads and are less frequently associated with malignant germ cell tumors than gonadoblastomas.

Gonadoblastoma

Gonadoblastoma is a rare ovarian lesion that consists of germ cells that resemble those of dysgerminoma and gonadal stroma cells that resemble those of a granulosa or Sertoli tumor. Sex chromatin studies usually show a negative nuclear pattern (45,X) or a sex chromosome mosaicism (45,X/46,XY). Gonadoblastomas usually arise in dysgenetic gonads, but the presence of dysgenetic gonads, a Y chromosome, or a Y fragment is not required; very rare cases of gonadoblastomas have been reported in normal women with normal ovaries and a normal karyotype. Because patients with XY gonadal dysgenesis have a very high risk of gonadoblastoma and a nearly 100% risk of associated malignant germ cell tumor with advancing age, these patients are recommended to undergo prophylactic bilateral oophorectomy after puberty. Patients who have a gonadoblastoma usually have primary amenorrhea, virilization, or developmental abnormalities of the genitalia, and the discovery of gonadoblastoma is made in the course of investigation of these conditions. It is poorly understood why some patients with these lesions become virilized and others do not. Although there is a correlation between the virilization of patients with gonadoblastoma and the presence of Leydig or lutein-like cells, this relationship is not consistent, and some virilized patients have tumors free of these cells. Another common initial sign is the presence of a pelvic tumor. Most patients with gonadoblastoma (80%) are phenotypic women, and the remainder are phenotypic men with cryptorchidism, hypospadias, and internal female secondary sex organs. Among the phenotypic women, 60% are virilized, and the remainder appear normal. The prognosis of patients with gonadoblastoma is excellent if the tumor and the contralateral gonad, which may be harboring a macroscopically undetectable gonadoblastoma, are excised. Bilateral involvement is identified in approximately 50% of cases. The association with dysgerminoma is seen in 50% of cases and with other more malignant germ cell neoplasms in an additional 10%. In view of this, the concept that these lesions represent an in-situ germ cell malignancy appears valid. When gonadoblastoma is associated with or overgrown by dysgerminoma, the prognosis is still excellent. Metastases tend to occur later and more infrequently than in dysgerminoma arising de novo. Complete or partial regression of virilization usually occurs after excision of the gonads. Exogenous estrogen therapy is given for periodic bleeding. The authors leave the uterus even after removing both gonads. Cyclic hormone therapy is indicated in these young women. Ovum transfer has been successful in patients who have had both ovaries removed. Although gonadoblastomas themselves are benign, treatment should follow the usual tenets for surgical staging if a malignant component is identified.

Mixed Germ Cell–sex Cord Stromal Tumors