Jean Woo

Geriatrics in Asia

There is varying information about older adults in countries other than Europe and North America. In general, characteristics of older adults in Asia are similar, depending on the degree of economic development; however, health and social care systems are different. This chapter describes the impact of demographic and economic changes on life expectancy, morbidity, disability, and frailty and responses of health care systems to these changes.

Life Expectancy, Morbidity, Disability, and Aging Well

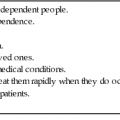

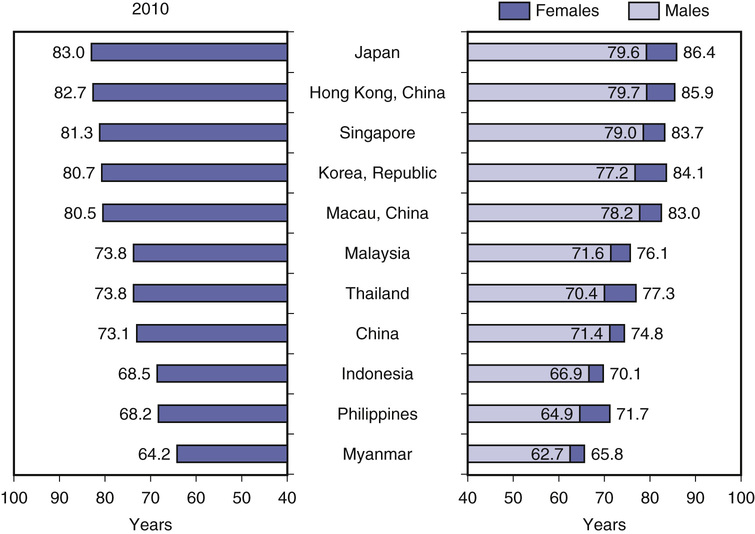

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2012 health data1 from selected Asian countries, life expectancy at birth ranges from 79.6 years for men and 86.4 years for women in Japan to 52.7 years for men and 65.8 years for women in Myanmar (Figure 122-1). Men in Hong Kong, China, enjoy the highest life expectancy among the world, 79.7 years. At the same time, the rate of population aging for many Asian countries is higher than in many developed economies. For example, the projected growth of population aged 60-plus years between 2012 and 2050 is projected to increase 2.7 times in China and 3.0 times in Indonesia.2 As for Europe and the United States, chronic diseases is the major morbidity burden for high-income as well as lower middle income countries in Asia, such as Japan, Republic of Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Although China is not considered a low-income country overall, nevertheless, in some rural areas, there is a double burden of communicable and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). Heart disease, stroke, and diabetes are the major NCDs. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), expressed as rate per 100,000 population, range from the lowest in Singapore (14,354) to the highest in Myanmar (48,793; Figure 122-2).3

Statistics of particular relevance to aging populations relating to dependency in activities of daily living (ADLs) are not widely available. The largest data set has been provided by the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study carried out in 2000, consisting of a sample of 11,199 older Chinese from 22 provinces of China. Among those aged 60 years and older, 38% reported difficulty with ADLs, 24% reported needing help with ADLs, 40% showed symptoms of depression, and 23% lived in poverty (http://charls.ccer.edy.cn/en). Two disorders were major contributors to disability—chronic pain and depression; 33% (39% women, 28% men) of older adults aged 60 years had chronic pain. The suicide rate per 100,000 for those older than 70 years was 51.5 in China, 25.5 in Japan, and 25.4 in Hong Kong, compared with 6.3 in the United Kingdom and 16.5 in the United States. This difference may be a reflection of cultural and service provision differences.

Political and economic factors play a contributory role. In China, market transition, as defined by the proportion of non–state-owned sector employees among the total number of employed persons, was shown to be positively associated with an individual’s likelihood of aging successfully, independent of socioeconomic status, social support, and lifestyle factors.4 This finding highlights the fact that the health of older adults is a function of medical, social, and political factors, so that strategies for improvement should adopt an integrated approach, as indicated by the Global Age Watch Index. The overall index is calculated as a geometric mean of four domains, of which health status is one; the others are income security, employment, and education, and enabling environment.2 The health status domain is constructed from data on life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at 60 years and psychological well-being. For Asian countries with available data, among a total of 91 countries, Japan ranked 10, China 35, Thailand 42, Philippines 44, Vietnam 53, South Korea 67, Indonesia 71, and Cambodia 80. For the health domain, Japan ranked 5, South Korea 8, Vietnam 36, Thailand 46, China 51, Indonesia 65, Philippines 70, and Cambodia 88. It can be seen that the health of older adults should not be considered in isolation but should be considered together with other domains for achieving the goal of aging well.

Trends in Prevalence and Incidence of Common Chronic Diseases and Geriatric Syndromes

It is important to document temporal age-specific trends in common chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes affecting older adults to assess the impact on health care and social services in terms of care burden and economic costs to inform service planning. However, few countries collect such data. An example of the type of data required for health and social care planning for aging populations is provided from data recently compiled in Hong Kong, as noted in the following sections.

Diabetes

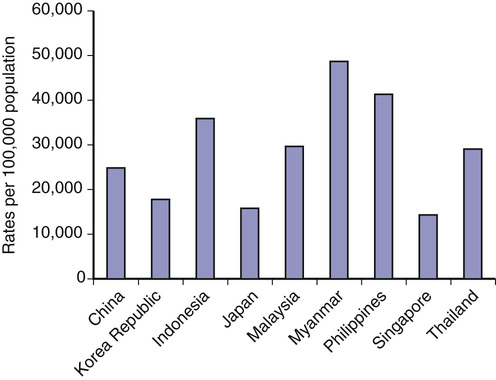

Data on incidence among Asian populations are sparse, but there is a suggestion that incidence is higher among Chinese. A population survey carried out among Hong Kong Chinese estimated the incidence of self-reported diabetes to be 55.6/1,000 people aged 65 years and older in 2003-2004.5 At the same time, the age-adjusted mortality rates from diabetes has shown a declining trend in the past decade, from 90 to 50/100,000 population. These figures are comparable to those for Japan, with both lower than those for the urban population in mainland China, as well as available data from the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia (Table 122-1).6–8 The self-reported prevalence in the Chinese population is similar to those reported for whites—12% for those older than 75 years and 14% for 65- to 74-year-olds. However, the prevalence based on glucose measurements is higher at 23% and 20% for women and men aged 65 to 84 years. Diabetes in older adults increases the risk of functional limitations from 1.5- to 4-fold and predisposes to poorer health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms. The attributable medical costs of diabetes in the public sector for older adults have been projected to be U.S. $0.46 billion in 2036.

TABLE 122-1

Mortality Rates from Diabetes in Hong Kong, China, and Japan

| Study | Country | Year | Age (yr) | Mortality Rate (Per 100,000 Population) |

| Healthy HK, Department of Health of Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region6 | Hong Kong | 2007 | 65-74 | 22.6 |

| 75-84 | 64.1 | |||

| 85+ | 141.0 | |||

| Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, 20107 | China (urban areas) | 2007 | 65-69 | 51.6 |

| 70-74 | 106.9 | |||

| 75-79 | 198.2 | |||

| 80-84 | 268.5 | |||

| 85+ | 361.6 | |||

| Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, 20088 | Japan | 2006 | 65-69 | 18.0 |

| 70-74 | 27.9 | |||

| 75-79 | 41.6 | |||

| 80-84 | 62.6 |

Ischemic Heart Disease

Disease burden is a function of disease incidence and case fatality rate. Trends in these figures for any population will be useful in planning preventive and hospital service programs. However, such data are not readily available. For white populations, incidence and case fatality rates have shown diverse trends, with a slow decline in the United States and a trend toward increase among certain age groups in England and Wales. Between 2000 and 2009, no overall decline in incidence was observed among a Chinese population in Hong Kong. However, the incidence for men 15 to 24, 35 to 44, and older than 85 years has shown an increasing trend, whereas those for other age groups have shown a decreasing trend. Case fatality rates remained have unchanged except for men aged 55 to 64 and 75 to 84 years and women 65 years and older. The increasing prevalence of hypertension may account for this observation.9

Stroke

Available data during 1999 to 2007 has shown that the trend for age-adjusted ischemic stroke incidence declined in a Hong Kong Chinese population, similar to observations for white populations, although the incidence is higher. However, the overall incidence of hemorrhagic stroke remained static, except for those 35 to 44 years of age.10 Although the incidence of stroke was lower in women, the case fatality rate was higher in women 85 years of age and older.11 Spatiotemporal variations in incidence and case fatality rate were also observed.12 Among older Chinese stroke survivors, poor health-related quality of life, depression, social participation, loss of self-esteem, loss of functional independence, and poor self-rated health have all been documented.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an important cause of functional limitation and dependence among older adults. Psychosocial consequences include poorer health-related quality of life and depression. Data for the incidence of COPD are sparse. In Japan, the incidence rate of clinically diagnosed COPD/1000 person-years among those aged 65 to 69 years was 27.5 for men and 16.9 for women; among those aged 70 to 74 years, the rates were 49.5 for men and 20.5 for women. Rates were lower among Hong Kong Chinese, based on self-reported data only.13 The mortality rate/100,000 population is highest in mainland China (approximately 130), compared with much lower rates in Hong Kong and Singapore (≈20). The difference is likely to be a consequence of smoking and air pollution.

Hip Fracture

From the 1960s until 2000, hip fracture incidence increased in the Hong Kong Chinese population. From 2001 to 2009, the age-adjusted incidence rate per 100,000 population of hip fracture among those aged 65 years and older in Hong Kong started to decline, from 381.6 for men and 853.3 for women to 341.7 for men and 703.1 for women, with no significant changes in postfracture mortality trends.14 This follows the pattern of economically developed countries, which initially showed an increasing trend that declined following a peak.

Dementia

The percentage of community-dwelling people aged 60 years and older in Hong Kong with dementia13 increased from 0.6% in 2009 to 1.1% in 2004 and remained stable until 2008. The percentage of older adults aged 70 years and older with clinically diagnosed dementia increased from 4.5% in 1995 to 9.3% in 2005 to 2006 and approximately doubled every 5 years until 90 years of age; the prevalence was higher in women compared with men. Approximately 30% of people aged 60 years and older living in residential care homes have dementia. Age-adjusted mortality rates for dementia (per 100,000 population) for those aged 60 years and older have shown an increasing trend from 2001 (23.3 for men and 47.3 for women) to 2009 (45.6 for men and 62.0 for women). These figures are comparable to those of mainland China, lower than among whites in the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia, but higher than Japan and Singapore. Increasing awareness and diagnosis may account for the increasing trend. However, increasing trends of prevalence of midlife risk factors, such as low physical activity, hypertension, and diabetes, may also contribute to the increase in late-life dementia.15 These trends represent considerable challenges to long-term care in community and residential care settings and highlight the need for capacity building and adaptations in health care settings when caring for those with dementia.

Frailty

The concept of frailty has been recognized among geriatricians in Asia. Frailty has primarily been a topic of epidemiologic research using the phenotypic model developed by Fried and colleagues16 as well as the multiple deficit model proposed by Rockwood and associates.17 Studies using both definitions have been carried out in the Hong Kong Chinese population and showed the ability of this measure to predict mortality, functional, and cognitive decline, as well as the susceptibility of those with frailty syndrome to social and environmental factors.18–22 This is in accord with the concept of frailty being multidimensional. Similar studies on population prevalence and risk factors have been carried out in Malaysia23 and community-dwelling older adults in Beijing, China.24 A frailty index was constructed using the multiple deficit model for the Beijing Longitudinal Study of Aging II Cohort. Using an empirical cutoff value of 0.25 or higher, the overall prevalence of frailty was 13%. The prevalence was higher in women and higher in those 85 years of age and older (33% for women and 18.5% for men). Urban living, being single, daily exercise less than 30 minutes, daily sleep less than 6 hours, having three or more chronic diseases, and taking four or more medications were risk factors for frailty. At 12 months, frailty increased the risk of falls, hospital admission, ADLs, dependency, and mortality. In Japan, the Kihon Checklist, an assessment of frailty, is used routinely in long-term care management plans.25

The incorporation of some assessment of frailty into everyday clinical practice has been limited as a result of the need to operationalize the criteria. The FRAIL score,26 a brief assessment consisting of five questions, may be suitable for clinical practice or population screening. It has been shown to have similar predictive characteristics as other scales. It is quick and may be applied by non–health care professionals. Recently, it has been used in frailty screening of community-living older Chinese aged 65 years and older in Hong Kong. The score was initially determined by volunteers—12.5% were identified as frail, 52% as prefrail, and 35% as robust. These proportions were similar to those from large-scale epidemiologic studies.23,24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree