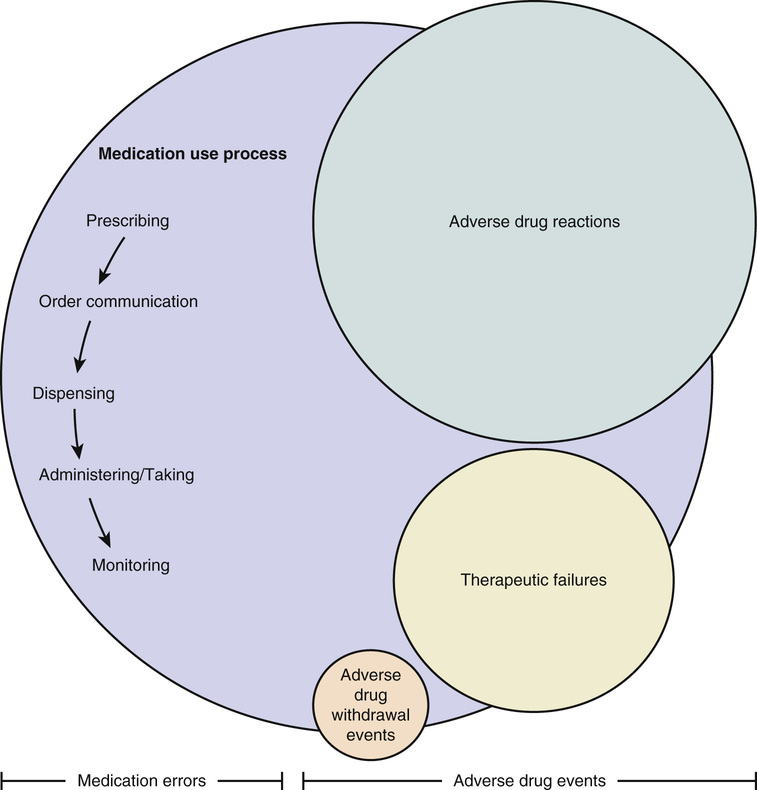

Jennifer Greene Naples, Steven M. Handler, Robert L. Maher Jr., Kenneth E. Schmader, Joseph T. Hanlon Medications are the most frequently used and misused therapy for the medical problems of the aged. Geriatric health care professionals and their patients rely heavily on pharmacotherapy to cure or manage diseases, palliate symptoms, improve functional status and quality of life, and potentially prolong survival. In the past several decades, knowledge about the epidemiology and clinical pharmacology of drugs in older adults has increased dramatically. The purpose of this chapter is to identify issues related to the efficacy and safety (including medication-related problems) of pharmacotherapy in older populations, to examine approaches to reduce these problems, and to discuss principles of optimal geriatric pharmacotherapy. Historically, older adults have been excluded from clinical drug trials, thereby limiting knowledge regarding the efficacy and safety of geriatric pharmacotherapy.1 There are, however, encouraging signs that this pattern is changing. For example, evidence for the efficacy of medications in older patients has been bolstered in recent years by a number of seminal randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) for geriatric conditions (e.g., behavioral complications with dementia) and diseases (e.g., hypertension).2,3 The advent of linked administrative databases for pharmacy, laboratory, hospital, and outpatient visits should allow the execution of studies large enough to detect differences in effectiveness and safety of currently marketed drugs in older adults.4 In addition, the future seems bright for medication discoveries that may benefit older people, as nearly 435 new medicines in the United States are currently in phase I to phase III testing.5 Organizations responsible for safe medication use have also formally endorsed this shift in clinical research. In 2011, the European Medicines Agency published a document stating it “will ensure that the assessment process gives adequate consideration to the information available to ensure safety and effective use of products in older adults.”6 A similar supportive call to improve the inclusion of older adults in clinical drug trials was published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.7 Currently, however, there is a paucity of information about the efficacy and effectiveness of available drugs, especially in the frail oldest-old (i.e., those individuals aged 85 years or older). Thus, it is difficult for prescribers to use evidence-based medicine to choose the most appropriate drug therapy for frail older patients while avoiding medication-related problems. Information about medication-related problems is derived from postmarketing observational studies of specific therapeutic classes or conditions. Issues commonly associated with medication use include medication errors and adverse drug events (ADEs) (Figure 101-1).8 A medication error can be defined as “an event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer.”8–10 These errors may occur at the prescribing, order communication, dispensing, administration/taking, or monitoring stages of the medication use process and are considered preventable. Medication errors may result in an ADE, defined as “an injury due to a medication.”9 Of the three different types of ADEs, the most common is an adverse drug reaction (ADR), classified as “a response to a drug that is noxious and unintended and occurs at doses normally used for the prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for modification of physiological function.”11 The second type of ADE is an adverse drug withdrawal event (ADWE), characterized as “a clinical set of symptoms or signs that are related to the discontinuation of a drug.”11,12 Lastly, a therapeutic failure (TF) is defined as “a failure to accomplish the goals of treatment resulting from inadequate drug therapy and not related to the natural progression of disease (e.g., omission of necessary medication therapy, inadequate medication dose or duration, and medication non-adherence).”11 Recent studies of medication errors and ADEs in older adults have been described in annual summaries.13–18 The following sections describe some of the most pertinent studies pertaining to the epidemiology of these three distinct types of ADEs. Emergency department evaluation and hospitalization are some of the worst adverse consequences of pharmacotherapy. A meta-analysis of older studies found that 16% of all hospitalizations in older adults were because of ADRs.19 A more recent systematic review identified seven additional studies between 2000 and 2013 in which hospitalization rates ranged from 5.0% to 30.4%.20 This review, however, did not include two important studies from the United States. In the first, Budnitz and colleagues identified 5077 cases of ADRs over a 2-year time period, which extrapolated to 98,628 hospitalizations of adults older than 65 years; nearly half involved patients aged 80 and older.21 In the second study of 678 veterans who were at least 65 years old, 10% of unplanned hospitalizations over 2 years were determined to be related to an ADR according to the Naranjo ADR causality algorithm.22,23 Of these, only 36.8% were deemed preventable, with suboptimal prescribing identified as the primary precipitator. Extrapolation to the U.S. population of older veterans receiving primary care suggests that approximately 8000 would have been hospitalized secondary to an ADR. Few investigators have studied ADRs in older outpatients or nursing home residents. In a large cohort study of 27,617 older ambulatory adults, 5.5% experienced an ADR over the 12-month study period, of which 27.6% (421) were considered preventable.24 Another prospective cohort study of 626 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older with mobility limitations found that 38 (22%) self-reported an ADR.25 Finally, a retrospective cohort study used a causality algorithm to examine the prevalence of type A ADRs (i.e., ADRs due to an exaggeration of the expected pharmacologic effect of a drug) in ambulatory adults.26 Among 359 frail older veterans transitioning from hospital to community and prescribed a high-risk medication, 31.8% were found to have one or more type A ADRs rated at least “possible” on the Naranjo ADR algorithm scale.22,26 Gurwitz and colleagues studied the occurrence of ADRs in 18 nursing homes in the U.S. state of Massachusetts.27 Over a 1-year period, 2916 nursing home residents had 546 ADRs, an incidence rate of 1.89 ADRs per 100 resident-months. Overall, nearly 44% of ADRs were fatal, life-threatening, or serious, and 51% were preventable. Subsequently, Gurwitz and colleagues also examined the combined incidence of ADRs in two academic nursing homes.28 In this 9-month prospective observational study, 815 ADRs were detected among 1247 nursing home residents, an incidence rate of 9.8 ADRs per 100 resident-months. The majority (80%) of ADRs occurred at the monitoring stage of the medication use process and, as in the previous study, a large proportion (42%) was considered preventable. Collectively, these studies from a variety of settings demonstrate that ADRs are common phenomena in older patients. In published studies discussing ADRs in older adults, only polypharmacy has been consistently identified as a risk factor, although some have suggested that ADRs may be attributed to a select few medication classes (e.g., antithrombotics, antidiabetics, and opioids).21,29,30 Reducing the number of medications in older patients with multiple comorbidities may be challenging, however, because these concomitant diseases often require pharmacotherapy. It is also difficult to avoid drug classes most associated with ADRs because they are essential to the management of older persons. There is some evidence that specific types of medication errors (e.g., inappropriate prescribing, suboptimal lab monitoring, and medication nonadherence) increase the risk of ADRs. Inappropriate prescribing refers to the selection of a medication where either the risks associated with its use outweigh the benefits or utilization does not agree with accepted medical standards.31,32 Whether using explicit or implicit criteria, potentially inappropriate prescribing is common regardless of care setting, affecting 25% to 92% of older patients.33–35 Since the last edition of this book, four studies have been published that found inappropriate prescribing increases the risk of ADRs as measured by explicit criteria such as the Screening Tool of Older Persons (STOPP) and American Geriatric Society Beers criteria.25,36–38 Similar results were seen in five studies using a reliable and valid implicit measure, the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI).26,37,39–41 Drug-drug and drug-disease interactions may be the most important types of potentially inappropriate prescribing that increases the risk of ADRs.25,26 This is clinically sensible given that aging is associated with decreases in organ function and hemostatic reserve, changes in drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and increases in the number of comorbidities requiring drug therapy. Suboptimal monitoring may also increase the risk of ADRs in older adults.42,43 In the ambulatory care setting, a substantial proportion of older adults does not receive appropriate laboratory monitoring while taking chronic prescription medications.44,45 Indeed, as many as 70% of the ADRs in nursing homes are related to a failure to appropriately monitor medications.27,28 The most common medication adherence problem is underuse.46,47 However, the contribution of medication nonadherence to ADRs is likely minor, as older patients may be adherent with up to 75% of their total number of medications.48 Because ADWEs are not formally examined in clinical trials, practitioners must rely on clinical experience and published data in the postmarketing period to glean information about these problems.12,49 ADWEs may manifest either as a physiologic withdrawal reaction (e.g., β-blocker withdrawal syndrome) or as an exacerbation of the underlying disease.12,49 A 2008 review summarized data from clinical trials about the benefits and risk of discontinuing specific drugs/classes.50 Few studies have examined ADWEs when multiple different drug classes are discontinued in older patients. Of those presented here, all used causality algorithms such as the Naranjo scale. Overall, ADWEs were much less common than ADRs or TFs, rarely severe, and almost always preventable. Gerety and coworkers investigated ADWEs in a single nursing home in the U.S. state of Texas over an 18-month time period and found that 62 nursing home patients experienced a total of 94 ADWEs (mean 0.54 per patient), corresponding to an incidence of 0.32 reactions per patient-month.51 Cardiovascular (37%), central nervous system (22%), and gastrointestinal (21%) drug classes were most frequently associated with an ADWE. A study of ambulatory older patients by Graves and associates in the U.S. examined ADWEs in 124 patients. Of 238 drugs discontinued, 62 (26%) resulted in 72 ADWEs in 38 patients.52 Again, cardiovascular (42%) and central nervous system (18%) drug classes were the most frequently implicated. Only 26 drugs (36%) discontinued led to ADWEs that required hospitalization, emergency department evaluations, or urgent care clinic visits. Most of these ADWEs were exacerbations of an underlying disease, and some withdrawal events occurred up to 4 months after the medication was discontinued. In a study by Kennedy and colleagues, ADWEs were investigated in the postoperative period at a single hospital.53 Of 1025 patients studied, 50% were older than 60 years. Thirty-four patients suffered postsurgical complications resulting from drug therapy withdrawal. Specific drug classes involved included antihypertensives (especially angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), antiparkinson medications (notably levodopa/carbidopa), benzodiazepines, and antidepressants. A retrospective chart review of 627 older patients in Japan evaluated the incidence of ADWEs for the first three months after admission to a long-term care facility. Of the 230 patients with medication reduction, only 5 (2.2%) experienced an ADWE. Discontinuation of antipsychotics resulted in confusion in three cases. Relapse in depression and hyperglycemia were seen in the other two cases after stopping antidepressants and sulfonylureas, respectively.54 Recently, case reports suggest that the abrupt cessation of donepezil may also be associated with ADWEs, including agitation and delirium, beginning approximately 3 to 5 days after discontinuation. In two cases where donepezil was restarted, symptoms resolved entirely.55,56 When donepezil rechallenge was not employed, symptoms fluctuated, disappearing by day 10 after cessation.55 No causality algorithm was used in these studies. Finally, a study in the U.S. examining medication changes between bidirectional nursing home and hospital transfers illustrated that half of the ADEs attributed to medication changes were the result of drug discontinuation.57 Little is known about the risk factors for ADWEs. In the study by Gerety and colleagues ADWEs were associated with multiple diagnoses, multiple medications, longer nursing home stays, and hospitalization.51 The number of medications stopped has also been shown to significantly predict ADWEs.52 Additionally, the risk of ADWEs may rise as the length of time off a medication increases.53 There are very few published trials examining TF in older patients. In a U.S. study of TF leading to hospitalization, investigators used the reliable Therapeutic Failure Questionnaire (TFQ) to measure causality in 106 frail older adults admitted to 11 Veterans Affairs hospitals.58 Eleven percent of these individuals had probable TF leading to hospitalization, with congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease representing the most commonly-associated comorbidities. Italian investigators found that 6.8% of patients in the emergency department had evidence of TF, with nearly two-thirds occurring in patients older than 65 years.59 A U.S. investigation of drug-related emergency department visits in older patients found that 28% of drug-related visits were due to TF.60 Using an implicit Likert scale, researchers on a geriatric hospital ward in Belgium noted that 9 of 110 (8.2%) admissions were due to TF, specifically resulting from nonadherence and subtherapeutic dosing.61 Marcum and associates also reported that, based on the TFQ causality algorithm, 34 of 678 (5%) veterans with unplanned hospitalizations had evidence of TF. Thirty-two instances were deemed preventable, as medication nonadherence and suboptimal prescribing were the most common reasons for TF.62 Risk factors for TF have not been clearly delineated. The most recently published study found that African American veterans were significantly more likely to experience TF-related hospital admissions than were white veterans.62 This may be because of lower medication adherence rates in African American versus white older adults.63 Other reasons for TF may include low prescribed doses, hepatic metabolism enzyme induction, drug interactions, drug resistance or nonresponse, inadequate therapeutic monitoring, or underprescribing of necessary drug therapies. Nonadherence was the most common reason for TF in two U.S. TFQ hospitalization studies (46% and 58%) and in the U.S. emergency department visit study (66%).50,58,62 Older patients may fail to fill or take their prescriptions, skip doses, take the drug erratically, or take reduced doses. These behaviors may be intentional (e.g., adverse effects, health beliefs, concerns about taking too many drugs) or unintentional (e.g., cognitive impairment, poor vision or dexterity, lack of transportation).42 Cost-related nonadherence is a particularly important and prevalent subtype of intentional nonadherence among older adults with limited means.63,64 Another major factor related to TF is the underprescribing of medications, defined as the omission of drug therapy indicated for the treatment or prevention of a disease or condition.65 A study that applied the explicit Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders criteria found that 50% of 372 vulnerable adults were not prescribed an indicated medication.66 The most common omissions were gastroprotective agents for high-risk users of nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in diabetics with proteinuria, and calcium and/or vitamin D for those with osteoporosis. Studies using the explicit START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the Right Treatment) criteria have reported rates of underprescribing of 22% to 74% in older patients.31,67–69 A group of U.S. investigators using the Assessment of Underutilization of Medication measure found evidence of medication underuse in 62% of 384 frail older patients at hospital discharge.70 The necessary drug classes most likely to be absent were cardiovascular agents (e.g., antianginals), blood modifiers (e.g., antiplatelets), vitamins (e.g., multivitamins), and central nervous system medications (e.g., antidepressants). Patients with greater comorbidity and limited ability to perform basic activities of daily living were at higher risk for undertreatment.

Geriatric Pharmacotherapy and Polypharmacy

Introduction

Efficacy and Safety of Pharmacotherapy for Older Patients

Medication-Related Problems in Older Patients

Epidemiology of Adverse Drug Reactions

Epidemiology of Adverse Drug Withdrawal Events

Epidemiology of Therapeutic Failure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree