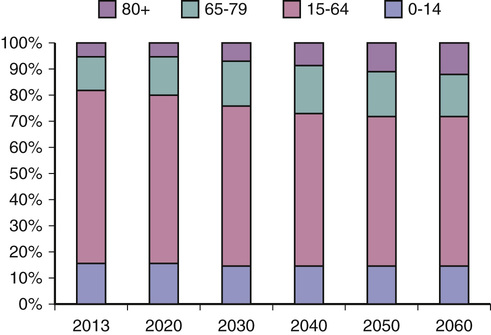

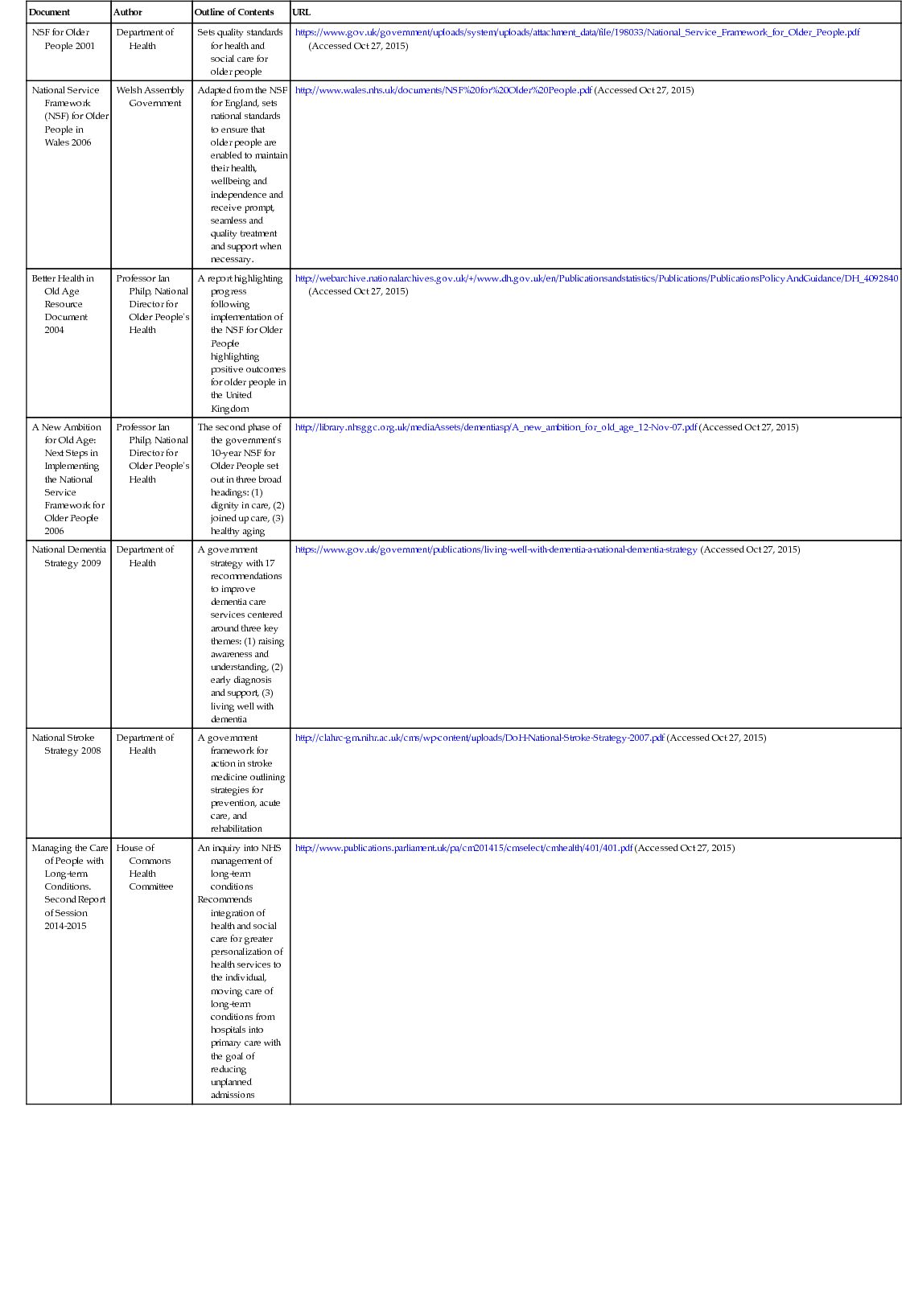

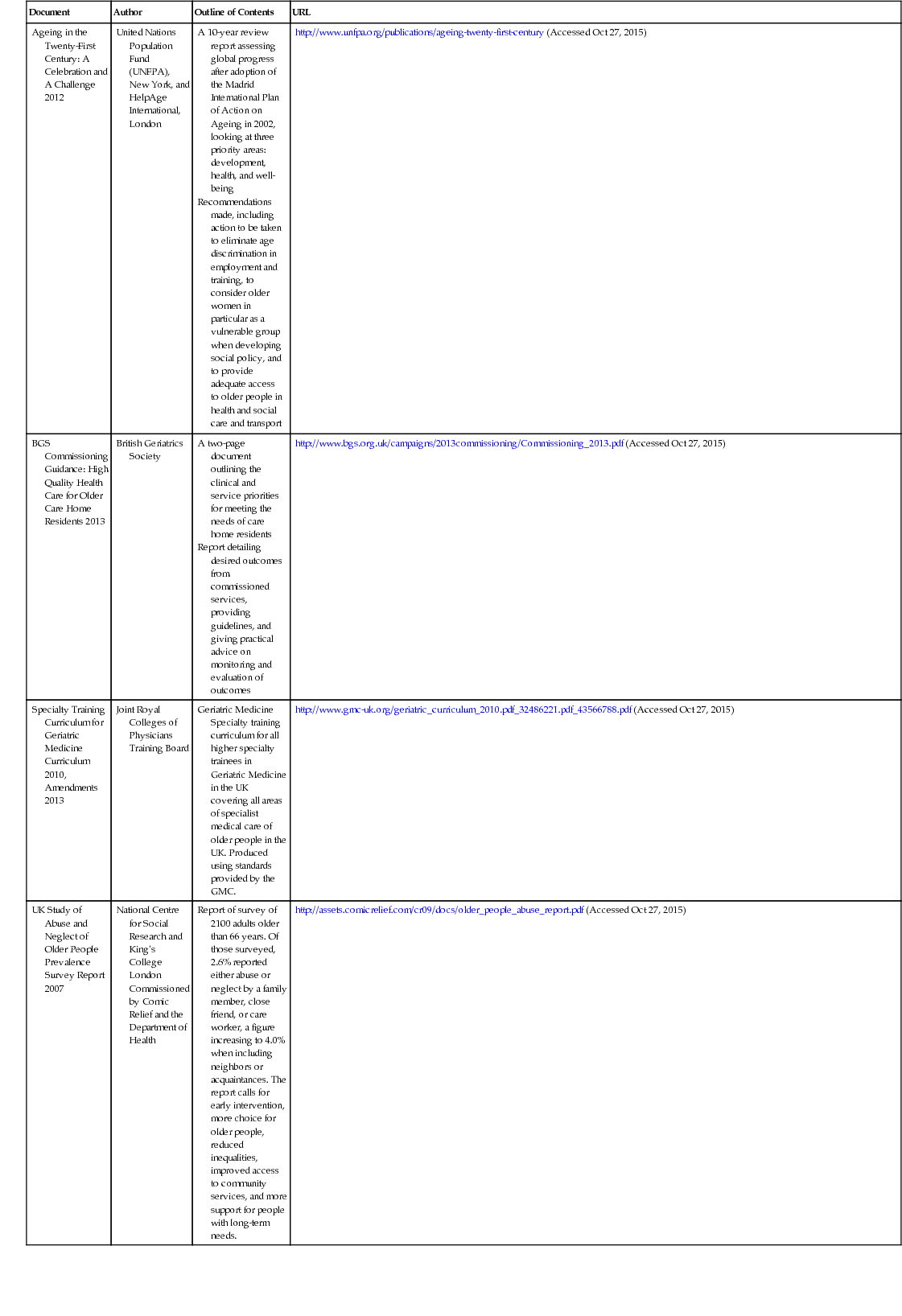

Peter Crome, Joanna Pleming In common with more developed countries throughout the world, population demographics throughout Europe will change dramatically in the next 50 years (Figure 120-1). In 31 countries (European Union plus the countries of the European Free Trade Association), the overall population of those aged 65 years and older was 16.0% in 2010 and is predicted to rise to 29.3% by 2060.1 The comparable figures for those aged 80 years and older are 4.1% and 11.5%, respectively, representing an almost tripling of the very old population. These differences are due to reduced fertility and increasing life expectancy; however, there remain differences in life expectancy between European countries. For example, the lowest projected life expectancy for males born in 2012 is 68.4 years in Lithuania compared to the highest of 81.6 years in Iceland. The differences between countries for women are not as great but still substantial at 79.6 years and 84.3 years for Lithuania and Iceland, respectively.2 The rationale for public policies to adapt to meet this population change is similar in all European countries. The need for specialized services for older people has also been recognized. Geriatric medicine as a distinct specialty has developed at different rates in different countries despite the needs of older people being relatively similar. This chapter summarizes the state of geriatric medicine in Europe and the work of organizations whose focus is improving the health of older people. The requirement that all citizens should have access to good-quality health care has been one of the principal features of European public policy. Different models have emerged based on state-funded systems, work-based or independent compulsory health insurance, or various combinations of the two. Some countries require co-payments, whereas others do not. There has also been recognition that older people are disadvantaged in terms of burden of illness, disability, frailty, and poverty in relation to the rest of the community. Special arrangements have been introduced in most countries to try and reduce these disadvantages. For example, in England all those older than 60 years do not pay for prescription medication. Citizens of the European Union are also entitled to health care in every EU country. However, the specific way health care is funded, and what services are provided and by whom, is a matter for national and, in some countries, regional determination. It is generally recognized that the definition of geriatric medicine as a distinct specialty resulted from the publications of Nascher in the United States.3,4 However, the development of a national geriatric medicine service has been credited to the United Kingdom and the pioneering work of Marjorie Warren, who implemented her service at the West Middlesex Hospital.5,6 Fortuitously, this interest coincided with the introduction of a new universal British National Health Service (NHS) in 1948, which incorporated from its foundation a network of hospitals that provided care for the chronically disabled, most of whom were older people. The history of the development of the specialty has been described in a previous edition of this textbook,7 and further information can be found in the excellent articles of Barton and Mulley 8 and of Morley.9 Therefore, only an abbreviated account is given here. Until the reformation, care for older disabled and sick people was provided under the auspices of the monasteries. These were closed during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547), and responsibility for this group of people passed to the civil authorities, who, as time went on, built institutions for their incarceration in what were called workhouses. The basic principle was that of “less eligibility,” with life being worse than that of the poorest laborer. The scandal of the workhouse, drawn to public attention through the work of Charles Dickens (in Oliver Twist, e.g.), led toward the end of the nineteenth century to the establishment of Poor Law Infirmaries, which in turn were transferred to the management of county and city municipalities in the 1920s. These hospitals became the first geriatric medicine hospitals in 1948. The arrangements of the NHS allowed for services to develop in accordance with local needs and the existing hospital structures. Three types of service were developed. The integrated model had geriatricians working alongside general internal medicine physicians, often sharing wards and support medical staff.10 Under the age-related model, medical emergency patients were admitted to geriatric medicine or general medicine services according to age, with those 75 years and older more frequently admitted to geriatric medicine services.11 The third model, the “needs-related” service, had geriatric medicine services taking responsibility for older people with complex needs but often not until their acute needs had been treated. In practice, many services were not so rigidly demarcated. The NHS came into being in July 1948 based on the principles of universality, and care was provided on the basis of need rather than the ability to pay. Devolution of political power to the nations of the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) has produced differences in organizational structures, financial arrangements for medical staff, and some patient co-payments for medication and dental services, but the underlying premise of “free at the point of use” remains. Private sector medicine is essentially geared to provide services for simple one-off conditions, whereas the management of chronic disease remains essentially within the NHS. All people are eligible to register with a general practitioner (GP), who now usually works in small groups or practices although “single-handed” practices remain. There is a right to register with a GP of one’s choice, but in practice this may be difficult for those in rural areas and those who live in underdoctored areas and with those doctors whose “list” might be closed. The range of services provided by the primary care team varies but might include therapy, minor surgery, and specialist outpatient clinics. In rural areas, they might dispense drugs. GPs undergo a 5-year training program after qualifying as a doctor. This 5-year program includes a 2-year foundation program, common to all physicians, followed by 3 years in a GP training program that comprises 2 years in hospital posts and 1 year in general practice as a trainee registrar. This may change to a 5-year training program in line with most other medical specialist trainee programs. There is, however, no obligatory requirement to have a placement in geriatric medicine or old age psychiatry, although this is a major part of general practice. Most GPs are independent contractors, who are paid by a combination of basic allowances, capitation fees, meeting specific service targets (e.g., identifying patients with hypertension), and fees per item of service. Other GPs are salaried, employed by the practice partners or by the local health service. Medical consultations involve no direct payment for all patients, and medications for people older than 60 years are free. GPs may have their competence in the specialty of geriatric medicine recognized through a diploma examination organized by the Royal College of Physicians in London and in Glasgow. A few GPs who undertake some degree of specialist work (e.g., falls investigation, care home medicine) may be employed as a General Practitioner with a Special Interest (GPwSI). They have to undergo specific training supervised by the local geriatrician. The training program for geriatricians lasts 9 years and has three components: the 2-year common foundation program, 2 years of core medical training, and 5 years of training in geriatric medicine and general (internal) medicine. Entry into training is competitive, and various assessment methods are used to monitor and confirm progress. Successful completion of training renders a physician eligible to apply for a consultant post. In addition, many hospitals will employ a number of physicians who have not completed the full training program and who work as assistants to consultants. Training takes place in the main teaching hospitals associated with medical schools, in smaller district general hospitals, and in the community. Responsibility for the organization and delivery of postgraduate training rests with the NHS rather than the university, which is only responsible for the first year of the foundation program. Full details of training can be obtained from the Joint Royal Colleges Training Board website (www.jrcptb.org.uk). The Federation of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom undertakes an annual census of the numbers and work practices of consultants in the medical specialties in the United Kingdom. Geriatric medicine is the largest of the medical specialties, with 1252 consultants in post in 2012. Geriatric medicine is the largest of the medical specialties, with 1332 consultants in post in 2014 (Table 120-1). It should be noted that only a minority of physicians practice general or acute medicine as a stand-alone specialty although it is expected that this will rise in the next few years with the reintroduction of acute medicine as a specialty. In contrast, in 1993 there were only 658 consultant geriatricians and the growth has been steady over the past couple of decades. Approximately one third of the consultant workforce is female, but it is expected that this proportion will also increase. Women form the majority of geriatricians younger than age 40 and the majority of trainees. TABLE 120-1 Number of Consultants in the Larger Medical Specialties in the United Kingdom (2014) The majority of geriatricians work as part of a multidisciplinary team based within an acute hospital. Geriatric medicine (often called care of the elderly or similar) is in turn usually placed within a medical division alongside specialties such as diabetes and respiratory medicine. Some geriatricians work in smaller community hospitals as community geriatricians. Referral to geriatricians is usually via the patient’s GP, from other consultants, or via emergency admissions. Local arrangements may now allow direct referral from community nurses, therapists, and social services. Typically there will be six or more consultant geriatricians in each acute hospital, with support provided by doctors at different stages of training. The standard care pathway is for emergency admissions to be transferred either directly to the most appropriate inpatient service or to an acute all-specialty assessment unit. Patients no longer needing the services of an acute hospital may be transferred to a range of step-down (now often called intermediate care) facilities in community hospitals and care homes. A range of enhanced home care services are also usually available for the first month or so after discharge from hospital. A list of important recent documents on health policy relevant to older people is contained in Table 120-2. TABLE 120-2 Recent United Kingdom Policy Documents Relevant to Geriatric Medicine An inquiry into NHS management of long-term conditions Recommends integration of health and social care for greater personalization of health services to the individual, moving care of long-term conditions from hospitals into primary care with the goal of reducing unplanned admissions A 10-year review report assessing global progress after adoption of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing in 2002, looking at three priority areas: development, health, and well-being Recommendations made, including action to be taken to eliminate age discrimination in employment and training, to consider older women in particular as a vulnerable group when developing social policy, and to provide adequate access to older people in health and social care and transport A two-page document outlining the clinical and service priorities for meeting the needs of care home residents Report detailing desired outcomes from commissioned services, providing guidelines, and giving practical advice on monitoring and evaluation of outcomes The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry, 2013 Also known as the “Francis Report” Most geriatricians have a subspecialty interest, such as orthogeriatrics, stroke, continence care, or falls investigation, and a few may practice exclusively or almost exclusively in this subspecialty. The training of geriatricians in acute care and in rehabilitation has made them ideally suited to lead the development of stroke care in separate acute stroke units. Most patients admitted to hospital with a stroke are now treated by geriatricians. Stroke has become a recognized subspecialty of geriatrics, neurology, general medicine, clinical pharmacology, and cardiovascular disease, although the number of physicians who have undergone the required extra training in stroke care is small. More than 80% of geriatricians take part in unselected medical emergency work, and geriatricians are the largest specialty providing this work apart from those working exclusively in acute and general medicine. Table 120-3 summarizes the specific responsibilities of a team of geriatricians working in one U.K. teaching hospital. More information on the work of U.K. geriatricians can be found in the report by Wykro.12 TABLE 120-3 Outline of Roles of Consultant Geriatricians in a Tertiary Center in London, United Kingdom Acute and rehabilitation geriatrics—allocated acute medical ward; responsible for all patients older than 80 years Proactive liaison service for all older or complex postoperative patients Acute geriatrics Clinical director Dementia lead Acute and rehabilitation geriatrics—allocated acute ward of 32 patients older than 80 years; ward shared with another consultant Participates in multidisciplinary community meetings to discuss patients with frailty who are living at home Stroke consultant Senior clinical lecturer Patients with stroke Academic post Infection control Acute and rehabilitation geriatrics Falls clinic Admission avoidance and ambulatory care geriatrics Clinical governance lead Acute geriatrics Orthogeriatrics lead Acute and rehabilitation geriatrics Proactive liaison service for all complex older patients undergoing elective and emergency surgery Comprehensive geriatric assessment of all patients with fractured neck of femur before and after surgery Acute geriatrics Admission avoidance and ambulatory care geriatrics Care home medicine Cardiology liaison Acute and rehabilitation geriatrics Admission avoidance and ambulatory care geriatrics Monthly consultation service in each of four nursing homes supporting GPs and reviewing patients requiring specialist input Acute geriatrics Community dementia lead Admission avoidance and ambulatory care geriatrics Acute and rehabilitation geriatrics Admission avoidance and ambulatory care geriatrics Once-weekly memory clinic based in the hospital Acute geriatrics Community frailty clinic Admission avoidance and ambulatory care geriatrics Acute and rehabilitation geriatrics Admission avoidance and ambulatory care geriatrics Home visits of geriatric patients identified by GPs as in need of comprehensive geriatric assessment but unable to attend hospital The continent of Europe is generally considered as extending from the Atlantic Ocean to the Ural Mountains. However, for largely political reasons other countries are often considered as part of Europe and of its organizations. Almost all countries on the continent are members of the Council of Europe, whereas a smaller number of countries are members of the European Union. There has not been a comprehensive review of the state of geriatric medicine in each of the countries of Europe. However, national societies have produced summaries of their own activities, key features of training, and the current state of development of the specialty for the websites of the European Union Geriatric Medicine Society (EUGMS) (www.eugms.org) and the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) (www.uemsgeriatricmedicine.org). Principal features are described here. Austria. The Austrian Society for Geriatrics and Gerontology is involved in research on the aging process and diseases in old age, the production of guidelines, and the organization of scientific meetings alone and in collaboration with other German-speaking countries. Undergraduate medical education in geriatrics occurs mainly as noncompulsory lectures and seminars within other subjects. Geriatric medicine was established in July 2011 as a subspecialty of internal medicine, neurology, psychiatry, rehabilitation medicine, and general practice (www.em-consulte.com/en/article/765978). In 1999 the Austrian Federal Institute for Health Care (OBIG) commissioned an expert panel to address whether specialist geriatric departments were required in hospitals where previously older patients had been cared for under general medical teams. This report led to the proposal that a network of specialist geriatric treatment units (geriatric acute care and remobilization units) be required in the acute sector. This proposal was adopted in 2000. To date, 40 such units have been established in 61 hospitals (http://geriatrie-online.at/english/). The society publishes two journals: Geriatrie Praxis Österreich and Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie. Belgium. Geriatric medicine has been recognized as a full specialty since 2005. Approximately 330 geriatricians serve a population of 10 million people living in Belgium. There is a geriatric department in each of the 120 general hospitals in Belgium which equates to approximately 6 geriatric beds per 1000 patients (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/belgium.html; http://www.uemsgeriatricmedicine.org/uems1/belgium1.asp). The Belgian Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics organizes two conferences a year. Bulgaria. Bulgaria’s health expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product is one of the lowest in Europe. Much of the care of older people following hospital admission is still provided by families. The difficulties in providing postacute care have been discussed since the change of government in 2009, and the most recent health care provider contract contains an earmarked portion for selected postacute conditions. The Bulgarian Association on Aging was founded in 1997 although there were other societies previously. The association holds regular meetings for its multidisciplinary membership. With regard to training, optional geriatric training courses for undergraduates have been instituted in Sofia Medical School, although the uptake among medical students has been poor (http://www.uemsgeriatricmedicine.org/uems1/bulgaria1.asp; http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/bulgaria.html). Czech Republic. In the Czech Republic, geriatric medicine is a separate subspecialty within internal medicine. It is included in the undergraduate curriculum. Postgraduate medical training has been restructured twice, first in 2004 and again in 2009. Since 2006, approximately 20 centers have been accredited for a specialist geriatric training program, which lasts 4 years (http://www.uemsgeriatricmedicine.org/uems1/czech1.asp). The Czech Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics (CGGS) is involved in the development of clinical practice, education, research, and national and regional government policies. It organizes scientific conferences and publishes the Česká Geriatrická Revue. Geriatric medicine in the Czech Republic still faces a number of challenges, including low numbers of acute geriatric beds and long waiting lists for institutional care, but it has made progress recently in community geriatrics (http://www.uemsgeriatricmedicine.org/uems1/czech1.asp). The National Action Plan Supporting Positive Ageing for the period 2013-2017, adopted by the Czech Republic in February 2013, aims to support senior citizens to remain independent and in their own homes through coordination of health and social care.13 Denmark. In Denmark geriatric medicine developed as part of the assessment for care home admission. Today, however, geriatricians are involved in all aspects of the care of older people, including care of older adult patients within the emergency department. Geriatric medicine is one of nine internal medicine specialties. All three medical schools in Denmark have a geriatric medicine curriculum. Geriatric medicine encompasses the spectrum of health care with specialist geriatric units offering acute care of older patients and geriatric teams providing evaluation and treatment at home, collaborating with primary care doctors and nursing staff (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/denmark.html). In a shift from an early focus on institutional care in the late twentieth century, Danish health care now aims to keep older people in their own homes for as long as possible. Services that facilitate this include a 24-hour public health nurse service, day care centers, respite care for caregivers, and a “Seniors Help Seniors” volunteer program aiming to create social networks and combat loneliness among the older population (http://www.globalaging.org/elderrights/world/densocialhealthcare.htm). Estonia. The Estonian Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics was founded in 1997 and has a multidisciplinary membership. Its mission includes geriatric training, raising the profile of older people, and organizing scientific conferences. In 2007 a training course in geriatric medicine was organized, supported by the Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs and the European Social Fund. The course trained 24 doctors to be the first geriatricians in the country. These doctors founded the Estonian Society of Geriatrics (EGERS) (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/estonia.html). Finland. Finland has one of the oldest geriatrics societies (founded in 1948), which organizes an annual conference and other symposia. Geriatric medicine is a recognized independent specialty previously having been a subspecialty of internal medicine, neurology, and psychiatry. Most geriatricians in Finland today work in primary health care settings although larger city hospitals have well-developed geriatric services. Only 25% of district hospitals surveyed in 2012 had a separate geriatrics department. There are professors of geriatric medicine in all Finnish medical schools, and geriatrics is a compulsory part of the undergraduate medical curriculum. Finland has a national exam that must be completed prior to entry into Finnish geriatric medicine higher specialty training. Postgraduate training was standardized in 2012, and specialization takes 5 years. Additionally, the Finnish universities recommend that, after specialization, an additional 10 days a year be spent training in a site external to the physicians’ usual place of work (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/finland.html). In early 2012 there were 239 practicing geriatricians with 171 trainees registered in the specialty (http://www.uemsgeriatricmedicine.org/uems1/finland1.asp). France. Geriatric medicine has been a standalone subspeciality since 2004. It is possible to specialize as a geriatrician from any medical discipline but the most common route is through internal or family medicine with the training lasting 4 years from medical specialties and 3 years from family medicine.21 The French geriatric society is the Société Française de Gériatrie et Gérontologie (SFGG) and it combines both geriatic medicine and gerontology. It is open to geratricians as well as professionals from allied fields including public health and psychology. There are 17 regional geriatric medicine societies and four daughter societies linked to the SFGG and there is an annual scientific meeting in December of each year. The SFGG publishes guidelines within geriatrics and is involved in national policy-making around the care of older people in France. SFGG’s published journal is La Revue de Gériatrie (www.sfgg.fr, http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/france.html). Germany. The first German Gerontology Society was founded in 1938, reconstituted after both World War II and the reunification of Germany. A separate medical geriatric society was founded in 1995. Geriatric medicine is recognized as a subspecialty of internal medicine, family medicine, neurology, and psychiatry, although there are variations in each of the Länder. The German Geriatrics Society favors a training program that graduates joint internal medicine–geriatrics specialists. Although geriatric medicine is a compulsory part of the curriculum, academic departments have only been established in a minority of medical schools. The German Geriatrics Society organizes scientific meetings and publishes two journals and a newsletter: the European Journal of Geriatrics (bilingual), the Geriatrie Journal (German), and Geriatrie online, the newsletter (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/germany.html). Greece. The Hellenic Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (HAGG) was founded in 1977. Its main goal is the enhancement of the quality of life and well-being of older people. It focuses on research and international collaboration with other gerontological societies and works with political and social bodies (e.g., the Greek Ministry of Health) and local authorities to advise on health and social care matters. HAGG organizes a national congress every two years. Hungary. The first Hungarian congress on gerontology as held in 1937 and the fifteenth World Congress of Gerontology was hosted in Budapest in 1993. Recognition of the specialty occurred only in 2000. In 2011, the Hungarian Association of Gerontology (HAGG), together with the National College of Geriatrics and Chronic Care, created a health initiative that would set up “active” geriatric units first in university hospitals and then in all major regions. This process was initiated in 2012. Specialization in geriatric medicine requires 5 years of dedicated subspecialty training, and the exit examination has both practical and theoretical components (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/hungary.html). Iceland. The Icelandic Health Care System is a tax-funded national health insurance with weighted contributions based on age; younger taxpayers fund two thirds and older people fund one third. Geriatrics is recognized as a subspecialty of internal medicine and is being considered as a subspecialty of family medicine. Although it is possible to train in geriatric medicine entirely in Iceland, trainees are encouraged to train overseas. Geriatrics is taught in the medical school, and the Icelandic Geriatrics Society was founded in 1989. In 2013 there were 17 fully specialized geriatricians. Geriatricians manage both acute and postacute inpatient wards, ambulatory care, and memory clinic outpatient services (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/iceland.html). The Gerontological Research Institute, established in 1999, has been involved in genetic and environmental research in collaboration with the U.S. National Institute on Aging (http://www.uemsgeriatricmedicine.org/uems1/iceland1.asp). Ireland. Ireland has traditionally spent less on health compared with other Western European countries, and this is reflected in generally lower numbers of specialists. The development of geriatric medicine in Ireland has in many ways paralleled that in the United Kingdom, although the first geriatrician was not appointed until 1969. These similarities include the presence of geriatricians in all general hospitals, the involvement of geriatricians in acute medicine on-call duties, and dual training in geriatric and general medicine. In 2003 O’Neill and O’Keeffe14 reported that there were 41 geriatricians in the country, the largest specialty within internal medicine. Two models of care existed: an age-related service in the major teaching hospitals and an integrated approach in smaller hospitals where there might be a solo geriatrician working alongside four or five other medical specialists. The pattern of postgraduate training is very similar to that in the United Kingdom, and there is cross-representation on many postgraduate training bodies. The Membership of the Royal College of Physicians (MRCP) in Ireland examination is recognized as equivalent to that of the MRCP UK. Most Irish geriatricians will have undertaken part of their postgraduate training in the United Kingdom or other countries. The Irish Society of Physicians in Geriatric Medicine was founded in 1979, but geriatricians are also active in the Irish Gerontological Society, whose membership extends into Northern Ireland, part of the United Kingdom. Italy. There are 34 specialist geriatric departments within universities in Italy. The national geriatric society, Società Italiana di Gerontologia e Geriatria (SIGG), was founded in 1950 and has a biogerontology, nursing, and sociobehavioral section in addition to its large clinical section. SIGG is one of the largest geriatric societies in the world, with 1872 registered members in 2013. It has conducted large-scale national studies and publishes a number of journals, including Aging Clinical and Experimental Research and Giornale di Gerontologia. It organizes an annual scientific meeting and a summer school for fellows. Luxembourg. The Luxembourg Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics was founded in 1985. It holds an annual conference and produces a journal, Journée de Gérontologie et Gériatrie, annually in October (http://www.eugms.org/index.php?id=126). Malta. Health care in the Maltese Islands is divided between the public and private sectors. All medical postgraduate training in Malta is undertaken overseas. There is one Department of Geriatrics with 11 consultant geriatricians working in this small island country. The Geriatric Medicine Society of Malta (GMSM), set up in 2006, represents the specialty of geriatrics in discussions and decisions surrounding training and links the geriatric community of Malta with the European geriatric community (http://www.gmsmalta.com/index.php). In 2013, GMSM had 24 members. In Malta, the department of geriatrics is primarily hospital based. Geriatricians also conduct several dedicated outpatient services, including falls and memory clinics, and provide a consultation service to care home residents. Orthogeriatric beds were set up in 2012 within the acute hospital setting for joint care management of patients with neck of femur fractures (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/malta.html). The Netherlands. Geriatric medicine was recognized as a specialty in 1982. The Dutch Geriatrics Society was founded in 1999 and publishes the Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie (Journal of Gerontology and Geriatrics) and holds an annual congress, Geriatriedagen. Geriatric departments exist in most hospitals in the Netherlands. In January 2013 there were 201 practicing geriatric consultants. All health care is funded publically, and health insurance is compulsory. Medical care in nursing homes is provided by specialists in chronic care and rehabilitation medicine (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/the-netherlands.html). Norway. In Norway geriatrics remains a subspecialty of internal medicine. Geriatrics is part of the undergraduate curriculum, and there are professors in Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, and Tromsø. The precise functioning of the geriatric medicine department varies from hospital to hospital. Recently, the Norwegian government legislated that every acute hospital should have an acute geriatric unit, and this is currently being implemented nationally (www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/norway.html). The Norwegian Geriatrics Society holds a scientific meeting every other year but also takes part in pan-Nordic congresses. Poland. The number of geriatricians in training is not keeping pace with the rise in the number of older people in Poland. A study in 2013 estimated that the ratio of geriatricians to citizens was 0.16 : 10,000 and that there would be an insufficient number of specialists in post to meet the needs of a growing older population. The need to improve GPs’ knowledge of geriatric medicine was stressed.15 The Geriatric Society in Poland promotes development of care of older people in Poland, supports research, and promotes education in geriatric medicine in undergraduate teaching and in the specialist curriculum. It has a journal, Geriatria. There are approximately 650 geriatric beds around the country with most districts having a geriatric unit. There is one geriatric hospital in Poland, in Katowice, which houses both acute and rehabilitation units. Geriatric medicine is taught in undergraduate curricula but is only compulsory in three universities, with optional classes provided in five other universities (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/poland.html). Portugal. Geriatric medicine is not yet recognized as an independent medical specialty in Portugal. Until 2010, there were no specialist geriatricians or specialist geriatric units within the country. Geriatric medicine teaching in Lisbon and Coimbra medical schools began in 2010, and the first geriatric unit was opened in Lisbon Medical University Hospital in the same year (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/portugal.html). Romania. The Romanian Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics (SRGG) was founded in 1957. It holds an annual scientific meeting that includes specialist programs for multidisciplinary teams. It supports an affiliate organization, the Association of Young Geriatricians, which aims to support junior colleagues by offering scholarships and prizes for outstanding achievements in research. These scholarships and prizes are presented at the annual congress. Spain. The Spanish Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology (Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología; SEGG) was founded in 1948 and has clinical, biological, and behavioral-social sections. In February 2013, SEGG had 2358 members; 70% of these were doctors from various specialties and the remaining 30% comprised allied health professionals, scientists, patients, and caregivers. In addition to a national conference, the society publishes Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología bimonthly. A second society, the Sociedad Española de Medicina Geriátrica (SEMEG) was founded in 2000 and holds biennial scientific meetings and has published a number of books. SEGG has significant e-media presence; it posts regularly on Twitter (@seggeriatira) and publishes an online newsletter e-mailed to members and available on the website (https://www.segg.es). A survey conducted in 2003 revealed that there were no acute geriatric care units in seven of the country’s regions amounting to two thirds of the country’s acute hospitals. This does not seem to have improved significantly, as a further study in 2009 revealed that only 12% of Spanish hospitals had an acute geriatric unit.16 Slovakia. Geriatric medicine is recognized as a specialty in Slovakia with training following European guidelines. Since the first four doctors gained geriatric specialization in 1983, more than 150 doctors have become specialists (http://www.eugms.org/index.php?id=132). The Slovakian Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology includes among its roles the dissemination of knowledge about older people to physicians and other health care workers, policy development, activities aimed at ending age discrimination, and organizing scientific meetings. Its journal, Geriatria, is published four times a year. Slovenia. Geriatrics is not yet recognized as a specialty in Slovenia. Older patients are cared for within family medicine, a branch of medicine containing a special working group for care of older adults and care within nursing homes. With regard to training, several specialties (including internal medicine, family medicine, and psychiatry) contain modules on geriatrics within their curricula. The Institute of Gerontology and Geriatrics was founded in 1966 but, with the death of its founder, Bojan Accetto, in 1988, the focus of the society moved from care of older adults toward vascular medicine. A multidisciplinary sister organization, the Slovenian Society of Gerontology, has taken on the role of older patients’ health advocacy, promoting gerontological research, participation in health and social care, legislation development, and public health information on age-related issues (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/slovenia.html). Sweden. Geriatrics is recognized as a full specialty in Sweden. Most geriatricians work in specialist services for older people with a minority working in primary care or internal medicine. The Swedish Society for Geriatrics and Gerontology organizes three scientific conferences each year and publishes the journal Geriatrik. There are six chairs of geriatric medicine within Sweden (in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malmö, Linköping, Uppsala, and Umeå), and all departments are very active in geriatric research (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/sweden.html; http://www.slf.se/Foreningarnas-startsidor/Specialitetsforening/Svensk-Geriatrisk-Forening/In-English/). Switzerland. Geriatric medicine was recognized as a specialty in 2000, and the Swiss Geriatrics Society was founded shortly after that in 2002. Before this time, geriatricians had formed a section of the Swiss Gerontological Society. The two societies share the same administrative office and are now collectively known as the SFGG-SPSG. Most geriatricians initially train in internal medicine before undertaking geriatric medicine specialization, but a small number first become family physicians. Specialist training comprises 2 years in geriatric medicine and 1 year in old age psychiatry after the 5 years in either internal medicine or family medicine. Training in geriatric medicine has improved in recent years, with seven hospitals now accredited to provide postgraduate training. The four university hospitals (Basel, Berne, Lausanne, and Geneva) have chairs in geriatric medicine (http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/switzerland.html). Geriatricians face the additional ethical challenge of assisted suicide, which is legal in Switzerland for Swiss nationals and foreigners (http://www.slf.se/Foreningarnas-startsidor/Specialitetsforening/Svensk-Geriatrisk-Forening/In-English/). (Assisted death is also legal in Belgium and the Netherlands but is restricted to nationals within these countries.) The SFGG-SPSG participates in meetings of the Swiss Society of Internal Medicine and participates in scientific meetings in French- and German-speaking neighboring countries. Turkey. In February 2013, Turkey had 47 geriatricians working in 14 geriatric medicine departments. There are two national geriatrics societies. The Turkish Geriatrics Society organizes conferences, arranges training courses for doctors and nurses, and participates in national and international events through its affiliation to outside bodies (http://www.turkgeriatri.org/index_en.php). The Academic Geriatrics Society, an organization founded in 2005, publishes the journal Akademik Geriatri Dergisi. The society’s aims include the promotion of health of older people, teaching about their health care needs, public education, and the organization of scientific meetings. Two regular meetings take place: the Rational Usage of Medications and Nutritional Products Symposium and the National Education for Nursing Home Personnel meeting (www.turkgeriatri.org and http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/turkey-turkish-geriatrics-society-observer-status.html, http://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/turkey-academic-geriatrics-society-observer-status.html).

Geriatric Medicine in Europe

Aging in Europe

Health Care in Europe

The Development of Geriatric Medicine

Geriatric Medicine in the United Kingdom

Specialists

Consultant Numbers

Specialty

Number of Consultants

Geriatric Medicine

1332

Gastroenterology

1170

Cardiology

1167

Respiratory

1135

Haematology

929

Endocrinology and Diabetes Mellitus

833

Neurology

783

Rheumatology

756

Dermatology

729

Renal medicine

610

Acute Internal Medicine

564

The Work of a Geriatrician

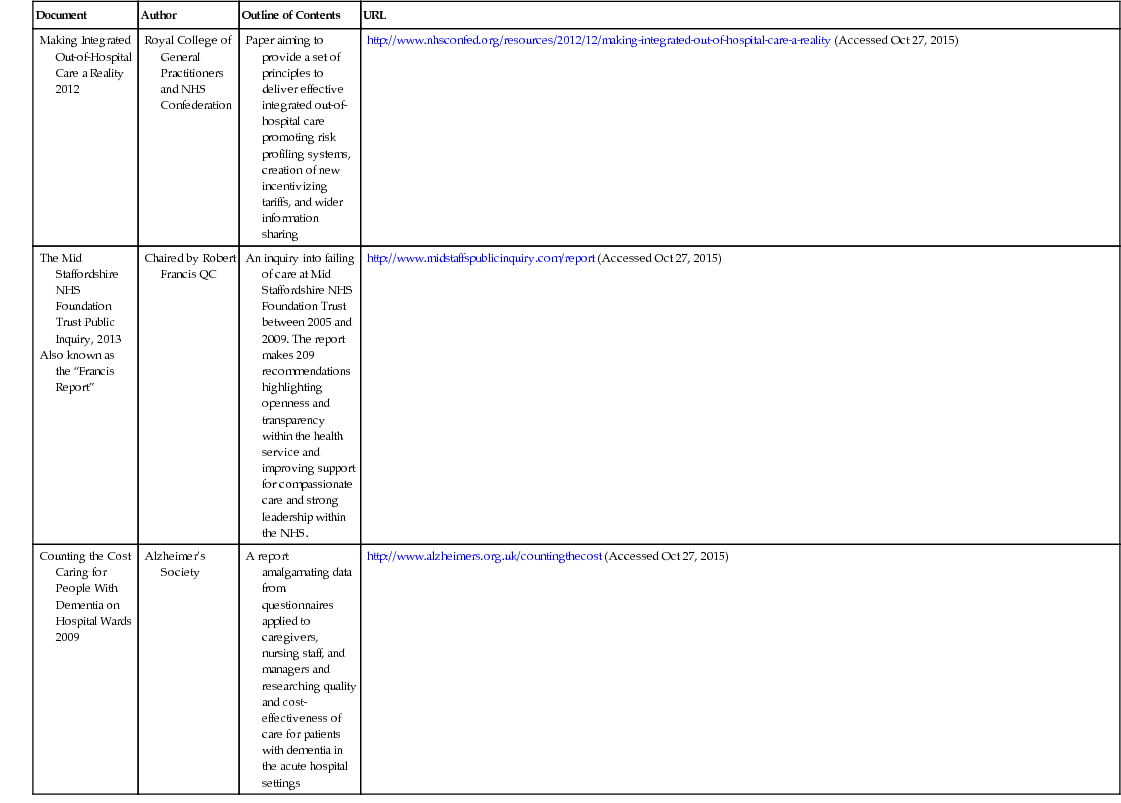

Document

Author

Outline of Contents

URL

NSF for Older People 2001

Department of Health

Sets quality standards for health and social care for older people

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/198033/National_Service_Framework_for_Older_People.pdf (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

National Service Framework (NSF) for Older People in Wales 2006

Welsh Assembly Government

Adapted from the NSF for England, sets national standards to ensure that older people are enabled to maintain their health, wellbeing and independence and receive prompt, seamless and quality treatment and support when necessary.

http://www.wales.nhs.uk/documents/NSF%20for%20Older%20People.pdf (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

Better Health in Old Age Resource Document 2004

Professor Ian Philp, National Director for Older People’s Health

A report highlighting progress following implementation of the NSF for Older People highlighting positive outcomes for older people in the United Kingdom

http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4092840 (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

A New Ambition for Old Age: Next Steps in Implementing the National Service Framework for Older People 2006

Professor Ian Philp, National Director for Older People’s Health

The second phase of the government’s 10-year NSF for Older People set out in three broad headings: (1) dignity in care, (2) joined up care, (3) healthy aging

http://library.nhsggc.org.uk/mediaAssets/dementiasp/A_new_ambition_for_old_age_12-Nov-07.pdf (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

National Dementia Strategy 2009

Department of Health

A government strategy with 17 recommendations to improve dementia care services centered around three key themes: (1) raising awareness and understanding, (2) early diagnosis and support, (3) living well with dementia

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/living-well-with-dementia-a-national-dementia-strategy (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

National Stroke Strategy 2008

Department of Health

A government framework for action in stroke medicine outlining strategies for prevention, acute care, and rehabilitation

http://clahrc-gm.nihr.ac.uk/cms/wp-content/uploads/DoH-National-Stroke-Strategy-2007.pdf (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

Managing the Care of People with Long-term Conditions. Second Report of Session 2014-2015

House of Commons Health Committee

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201415/cmselect/cmhealth/401/401.pdf (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and A Challenge 2012

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), New York, and HelpAge International, London

http://www.unfpa.org/publications/ageing-twenty-first-century (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

BGS Commissioning Guidance: High Quality Health Care for Older Care Home Residents 2013

British Geriatrics Society

http://www.bgs.org.uk/campaigns/2013commissioning/Commissioning_2013.pdf (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

Specialty Training Curriculum for Geriatric Medicine Curriculum 2010, Amendments 2013

Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board

Geriatric Medicine Specialty training curriculum for all higher specialty trainees in Geriatric Medicine in the UK covering all areas of specialist medical care of older people in the UK. Produced using standards provided by the GMC.

http://www.gmc-uk.org/geriatric_curriculum_2010.pdf_32486221.pdf_43566788.pdf (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

UK Study of Abuse and Neglect of Older People Prevalence Survey Report 2007

National Centre for Social Research and King’s College London Commissioned by Comic Relief and the Department of Health

Report of survey of 2100 adults older than 66 years. Of those surveyed, 2.6% reported either abuse or neglect by a family member, close friend, or care worker, a figure increasing to 4.0% when including neighbors or acquaintances. The report calls for early intervention, more choice for older people, reduced inequalities, improved access to community services, and more support for people with long-term needs.

http://assets.comicrelief.com/cr09/docs/older_people_abuse_report.pdf (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

Making Integrated Out-of-Hospital Care a Reality 2012

Royal College of General Practitioners and NHS Confederation

Paper aiming to provide a set of principles to deliver effective integrated out-of-hospital care promoting risk profiling systems, creation of new incentivizing tariffs, and wider information sharing

http://www.nhsconfed.org/resources/2012/12/making-integrated-out-of-hospital-care-a-reality (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

Chaired by Robert Francis QC

An inquiry into failing of care at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust between 2005 and 2009. The report makes 209 recommendations highlighting openness and transparency within the health service and improving support for compassionate care and strong leadership within the NHS.

http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/report (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

Counting the Cost Caring for People With Dementia on Hospital Wards 2009

Alzheimer’s Society

A report amalgamating data from questionnaires applied to caregivers, nursing staff, and managers and researching quality and cost-effectiveness of care for patients with dementia in the acute hospital settings

http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/countingthecost (Accessed Oct 27, 2015)

Consultant Number

Special Responsibilities

Activities

1

Acute geriatrics and surgical liaison lead

2

3

4

Falls lead

5

Lead and run admission avoidance service and ambulatory care clinic—direct referrals from general practitioners (GPs) and proactive identification of patients from emergency department who can be discharged with specialist nursing support in the community

6

7

8

9

Geriatric Medicine in Other European Countries

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree