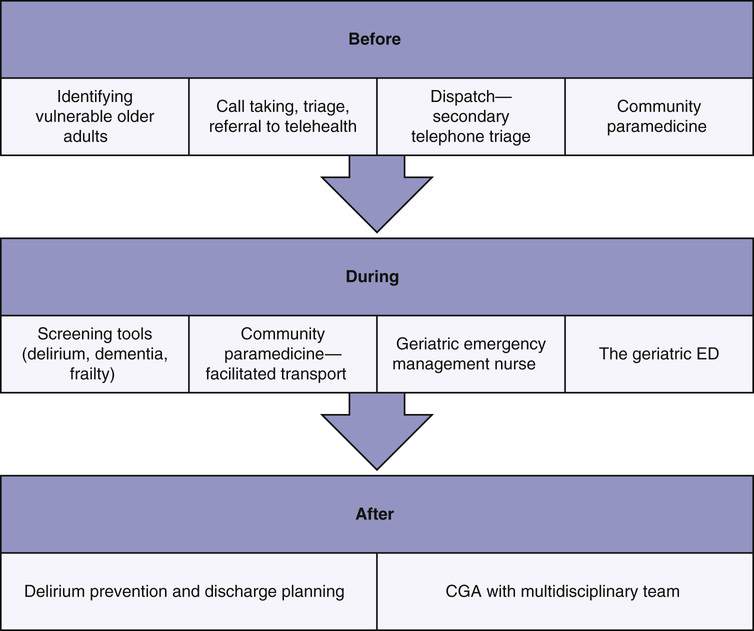

Jacques S. Lee, Judah Goldstein The arrival of the aging baby boomers has been anticipated for over a decade. The consequences are now beginning to be clear in emergency departments (EDs; British equivalent is accident & emergency [A&E]) worldwide. These aging baby boomers are challenging our North American preconceptions of what a typical older emergency patient looks like. Although the stereotype of the depression generation emergency patient has been characterized by increased risk for disease due to lifestyle and diet, stoicism that sometimes bordered on self-neglect, deference for the medical profession, and lack of comfort with technology, aging baby boomers challenge all these stereotypes. They may be very involved in fitness, resulting in sports-related injuries not previously seen among older adults. They can be extremely comfortable with technology and are more likely to have higher expectations and challenge physicians unlike previous generations. Currently, they often present accompanying their aging parent rather than as a patient, but may have young children in tow from a second or third marriage. Nonetheless, despite their improved lifestyle and diet, there is no evidence that these trends will eliminate disease or frailty. As a consequence, it is likely that older ED patients will show increasing variability from extremely fit to severely frail over the next 2 decades. Treating a stereotype instead of the patient in front of you has always been ill advised, and this increased variability among older patients poses an additional challenge for clinicians. Just as older patients will change dramatically over the next 20 years in character and in number, the approach of emergency and paramedic services to older patients must also change. The classic approach to emergency medicine was focused on the rapid assessment and treatment of otherwise healthy patients with a single-system problem. Emergency physicians can safely see up to three patients/hour, although they are sometime compelled to see more. Psychosocial issues were often considered outside the scope of emergency medicine. The ultimate goal of resuscitation and prolongation of life at any cost was never questioned. Emergency physicians typically make patient care decisions alone. In contrast, geriatric medicine involves the care of patients for whom multiple comorbidities are the norm, and challenging social circumstances are common. Their problems typically involve multiple systems, and psychosocial assessments are routinely needed. Extending the quantity of life may not be the overarching goal, focusing instead on quality. Also, geriatric medicine has pioneered the incorporation of an interprofessional and interdisciplinary team approach into decision making and care of such patients. The emergency management of older adults begins in the community, often with a request for paramedic assistance. Paramedics are among the only health providers that currently attend to most of their patients in the patient’s own home, which offers them the opportunity for unique insights into the home environment and clues to a patient’s functional status. Whether this information is gathered, how it is communicated, and how it might best be leveraged without duplication remain pragmatic challenges in most jurisdictions. In the typical case, patients who call emergency medical services are then transported to the ED. Even so, a large proportion of patient encounters do not result in transport to hospital (see later, “Epidemiology of Emergency Department and Paramedical Services Use”). Once in the ED, care is provided by the emergency providers and, depending on the presentation, a decision is made to discharge home or admit to the hospital. For those discharged, follow-up can be highly variable, ranging from instructions to return to the ED, if necessary, to proactive case management models by specialized geriatric emergency management professionals. These programs provide targeted interventions or alternatives to traditional care, with the goal to ensure the patients get the right care in the right place by the right provider at the right time. We will discuss some creative approaches to the challenges faced by older patients in the ED (see later, “Innovative Approaches to Older Patients in the Emergency Department”). In North America, paramedics typically staff emergency medical services (EMS) systems, with nurses present in some critical care transport models. In consequence, there has been a move to refer to paramedic services (PS) as opposed to emergency medical services. Other agencies throughout the world have varying staffing configurations, including physicians, nurses, and other allied health professionals. Paramedicine has been protocol-driven and focuses on targeted assessments, skills and interventions, and making decisions, often with medical oversight. As the education and professionalism of paramedicine evolves,1 more emphasis is being placed on clinical decision making and increased integration into the health care system. This chapter will primarily focus on the paramedic model, so will refer to these services as paramedical services. Paramedical services are a community-based resource, initially established to minimize morbidity and mortality from cardiac arrest (cardiovascular disease) to major trauma.2 The time it takes for a paramedic crew to arrive at the scene of a cardiac arrest has been shown to affect survival rates.3 As a result, paramedical services are designed to minimize response times to all patients in their geographic catchment area. This may result in relative underutilization of paramedic crews in rural settings with a low population density. In urban centers, paramedics may have extended wait times in hospital prior to patient handover to ED staff, known as off-load delay (see later). Paramedics provide care to the most vulnerable in society. In geriatrics, this would encompass the frail older adult. For these reasons, paramedics are uniquely positioned to play an important role in geriatric community-based care by merging primary and acute care services when there is a service request. Paramedics can serve as a conduit between primary and acute care to enable system integration and continuity of care, with the goal to improve the overall quality of care for this demographic and potentially improve system efficiencies. The term prehospital care is becoming a misnomer when considering the changes that are occurring in the realm of EMS. Services are evolving from the traditional transport service to more of an integrated health care service. Traditional paramedical services involved patient treatment and stabilization on scene, with subsequent transport, typically to the closest emergency department. Nontraditional paramedic roles can be referred to as expanded-scope paramedical services. In these nontraditional roles, paramedics assess patients and transport them to the most appropriate facility (e.g., trauma center, stroke center), provide referral services, or treat in place, in addition to the traditional idea of transport to the ED. Paramedics are caring for older adults for longer durations due to offload delay—the period of time between arrival at a health care facility and completing the handover to in-hospital staff—and, more frequently, with the closure of smaller health care facilities and regionalization of care (longer transports). Optimizing this care should be a priority for medical directors, EMS leadership, and other clinicians who may have a stake in care provision for older adults, including geriatricians. Paramedics receive little specific geriatrics training in their educational programs. Also, there is often a mismatch between the expectations of the job (e.g., classic expectations of trauma or cardiac arrests) and the reality, in which older adults with complex presentations comprise the bulk of care. This role dissonance might stem from paramedics identifying as rescuers but acting as care providers4 and can be a source of stress for EMS providers, especially in the traditional model of transport to the closest ED, with little thought regarding where the patient would be best managed. This is changing. In North America, close to 50% of paramedic emergency responses are for people 65 years and older.5,6 This is even higher in the United Kingdom, where 65% of older adults come to the ED by ambulance, compared with 20% of those who are younger age.7 Older adults comprise 12% to 24% of ED visits and this leads to high ED bed occupancy among this demographic.8,9 Older adults are often more acutely ill on arrival.9 They tend to have more medical tests performed in the ED, and this contributes to a longer length of stay in the department.9 Older adults also have more hospitalizations and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions.10 Adverse events are common in older adults discharged from the ED.10 In a study of U.S. Medicare beneficiaries, 32.9% of older adults discharged from the ED experienced an adverse event (e.g., readmission, hospitalization, institutionalization, death) within 90 days of the visit.11 Older adults are also more likely to be admitted to a nursing home following an encounter with emergency services.10 Paramedical services and ED use are expected to rise, especially in the oldest old.12 Older age is a major predictor of paramedical services and ED use.13 Even so, age does not fully explain these trends.14 Other contributors include the fact that older adults are living alone in their own home more often and there is reduced capability of caregivers and often difficulties accessing primary care.14 In addition, many chronic illnesses become more common with increasing age, increasing the likelihood of acute illness.15 Realizing that age is not the full contributor means that interventions or innovative models of care can be developed to serve this demographic in the community better. The need for less reliance on acute care services and a larger role for paramedics, emergency services, and intermediate and community-based care has been recognized,16 but moving away from acute care services is a challenge. Emergency medicine can play a role in facilitating this change. Frailty is an important predictor of adverse outcomes in the ED11,17; however, it is not well recognized as an important concept in this setting. Various approaches have been used to operationalize a definition of frailty within the context of emergency services. The prevalence of frailty, using the phenotype, was 20% in a cohort of older adults discharged from the ED.18 This was thought to be the “floor” of frailty because only discharged patients willing to participate were included.18 The frailty index (FI), a score based on the proportion of deficits or health problems of an individual, can predict adverse outcomes in patients seen in the ED and can be determined based on questionnaires completed by care partners.11,17 The FI likewise predicts outcomes in major trauma patients.19 Another approach uses the clinical frailty scale (CFS), which describes categories of increasing frailty and reduced function. Patients are placed in the category that best describes their current health.20 The CFS predicts adverse events in ICU patients21 and across a variety of other hospital settings22–27 and may represent a means to evaluate frailty in ED patients quickly. Different settings may require differing approaches that match the constraints of the setting. It is evident that frailty has been receiving more attention but more research is required to determine best practices. Novel programs to improve care for older adults should aim to include methods for improving the care for the frailest. Frailty is one of the predictors of emergency services use that can be better managed prior to ED arrival, in the ED, and during discharge. Here we outline existing, more progressive approaches, organized as before, during, and after. If emergency services are thought of as an episode of care, it can be further delineated in terms of decision points. When emergency services are accessed, it is possible to intervene during various nodes of the emergency episode of care continuum (Figure 117-1). When patients decide to access emergency care, there has typically been an acute change in condition or difficulties accessing other services (e.g., primary care).28 Calls for service are processed through dispatch centers, with ambulances dispatched as per local policies. The structured information obtained at this point determines the nature of the response. In addition, callers can be advised to initiate medical care. In most cases, the traditional paramedic response involves an ambulance, with varying paramedic configurations. In a number of locations worldwide, there are nontraditional paramedical services in the form of community paramedic responses that are often non–transport-capable. The responding paramedics conduct assessments and initiate treatment in the field. A decision to transport (or not) is made in consultation with the patient, family, and potentially medical oversight. In most cases, patients are still transported to the ED. The next transition point is the patient handover, or offload, period. In the ED, patients are assessed, treated, and discharged or referred for consultation within the department. Many older adults (≈20%) will be admitted.8 There are opportunities to improve the discharge process or transition of patients back into the community for the group not admitted. This is a group at high risk for further health decline immediately following the ED discharge.11 Throughout the continuum of care, there are opportunities to change how care is provided to address the individual’s unique needs. Paramedical services can be flexible, adaptable, and responsive to the demands of the system. We will highlight some of the ways the emergency system of care has changed to improve care provision for older adults. This often means using health care professionals in nontraditional ways. Paramedics are frequently requested to respond when a health crisis occurs in the community. Paramedics have been providing more care within the community that does not necessarily result in transport to the ED or, if it does, is described as a facilitated transport. Some of these programs span the continuum of emergency care and have an impact prior to ED arrival, within the ED, and on discharge. The goal of such programs is often ED diversion; however, care should also be patient-centric. Programs should focus on providing rational care that aligns with the patient’s (and care provider’s) preidentified goals of care. Some older adults are frail but not acutely ill and could benefit from community-based care, as opposed to direct transport to the ED, whereas others may be acutely ill and would benefit from the specialized knowledge, diagnostics, and treatments afforded by acute care. Discerning between these groups is a challenge. The subsequent section will describe promising programs at various points of the emergency continuum of care that aim to direct patients to the most appropriate resource or provide care differently. The first point of contact with the emergency system is with ambulance communication or dispatch centers. During primary telephone triage call takers triage calls, prioritizing them for dispatch using computer-based priority dispatch systems.29 Dispatch algorithms have been developed, such as the internationally used Medical Priority Dispatch System (MPDS). This system aims to identify high- and low-acuity patients so that the appropriate resources can respond. Dispatch centers may be staffed by civilian call takers and dispatchers or by paramedics or other health care staff. For this reason, health care knowledge can be variable. High-acuity conditions include cardiac arrest and major trauma. Low-acuity conditions may be more difficult to identify, especially in older adults. Nevertheless, programs are being developed to divert lower acuity calls to other services. In some systems, low-priority calls (omega priority) are transferred for secondary triage with a nurse or other advanced health care practitioner.30 Secondary telephone triage has been suggested as a mechanism to divert lower acuity calls by determining who might benefit from alternatives to ambulance transport. Secondary telephone triage appears safe; however, there are questions regarding its organization and impact on resource use.31 Up to 50% of low-acuity calls may be helped by medical advice alone,32,33 but this may be dependent on system-level factors. In a recent study, successful transfer to nurse triage without an ambulance response occurred in 12.3% of cases.30 There is also no information on how secondary telephone triage might work in the context of geriatrics specifically. In the traditional paramedical service, the focus is on a rapid response, focused assessment, identification of the chief complaint, and transport decision, with the idea to treat life-threatening conditions, provide symptom relief, and mitigate further deterioration in the patient’s condition. The definition, scope, and role of paramedics can vary among countries. For example in Canada, four levels are recognized (http://paramedic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/2011-10-31-Approved-NOCP-English-Master.pdf). The paramedic levels differ in degree of medical knowledge and types of delegated medical acts. At the advanced levels, there is enhanced assessment skills and the ability to implement invasive treatments and medications. Paramedics are differentiated from other health care practitioners by their degree of mobility, accessibility in the community (24 hours/day, 7 days/week), and ability to manage emergencies and provide comprehensive care in the out-of-hospital setting.34 Traditional paramedical services must be able to assess older adults competently, accessing emergency services and making sound decisions regarding care. In caring for older adults, studies have focused on identifying vulnerability via the development of risk screening measures and screening for cognitive impairment, depression, falls, immunization status, and frailty.35–37 Many of these programs have demonstrated that it is feasible for traditional paramedical services to screen for a variety of health care conditions, but few have assessed the validity of these instruments or follow-up interventions to improve health. There is also a lack of valid EMS measures to screen for mobility impairment, functional impairment, and caregiver burden. Paramedics often respond to older adults who have suffered a fall. A falls protocol has been evaluated for use in assisted living facilities to determine which patients might safely remain at home.38 This protocol uses the patient history and examination findings to recommend transport versus nontransport with primary care follow-up. Ground-level falls were broken down by tiers. Those in tier 1 include uncontrollable hemorrhage, lacerations requiring suture repair, acute medical conditions (e.g., ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI]), and others that would necessitate transport. Tier 2 cases include those with borderline abnormal vital signs, acute pain, and injuries requiring splinting. In these cases, a physician would be consulted, and then the decision to transport or provide care in place is made. Tier 3 cases (e.g., simple contusions or skin tears, no complaint, no hip pain and otherwise normal examination, no obvious injury) are recommended for no transport. The falls protocol had a sensitivity of 96%, specificity of 54%, and negative predictive value of 97% for predicting time-sensitive injuries.38 This is one example of a tool that can be used to support decision making in this setting. Safety and appropriate medical follow-up are key components to ensuring programs are successful. One of the biggest research priorities facing emergency services in relation to caring for older adults is whether critical illness can be diagnosed and treated effectively in a prehospital setting.39 Discerning between the frail older adult who is acutely ill and an older adult with a health care need but no acute illness is a challenge. Often, presenting complaints appear benign and are described as nonspecific40 (e.g., weakness, sudden onset immobility, falls) but, in the context of frailty, are indications of serious life-limiting, illness. Recently, a prehospital FI was found to have similar predictive properties as an in-hospital assessment (FI and comprehensive geriatric assessment [CGA]; FI-CGA).17 Determining frailty in the EMS setting, where there are often competing priorities and time constraints, is a challenge. The care partner FI-CGA (CP-FI-CGA) may be an efficient approach that captures the knowledge of care partners for frailty assessment. In this study, care partners were asked questions about the patients’ comorbidities, mobility, function, sensory impairment, and social supports.17 Responses were used to calculate an FI. This FI predicted 1-year mortality and demonstrated similar properties to other FIs. Whether the CP-FI-CGA can help guide care requires further evaluation. It may be possible to use this tool to discern among those who may benefit from community services versus those who would benefit in the ED. Once issues are identified, it may be possible to transport to the most appropriate non-ED provider, treat in place, or transport to the ED. In the context of other single acute conditions, systems of care have developed whereby paramedics use the assessment to determine the most appropriate health care facility for care. For major trauma, STEMI, and stroke, transport is usually to a tertiary care facility that specializes in providing care to these populations. A similar system of care may be beneficial for frail and acutely ill older adults. An emerging role within the paramedic profession is the community paramedic, and this may be valuable in geriatric emergency care. There are a number of terms used to describe the expanded-scope paramedic model; however, the one endorsed by clinical and operational leaders is the term community paramedic.34 A community paramedic is “a model of care whereby paramedics apply their training and skills in non-traditional community-based environments”1 (outside of the usual emergency response/transport model). Community paramedicine programs have been developed to take advantage of the idea that many presenting complaints can be cared for in the patient’s home or can be referred to other non–ED-based services, with potentially better outcomes, improved resource use, and patient satisfaction.34 Community paramedics should have the skill set to assess older adults within the community while operating within new models of care. These include more referral or transport options beyond the closest ED, additional resources, and improved linkages with other services, including primary care. The goal of such programs is to intervene prior to the emergency department visit by treating in place, referring to other services, or possibly facilitating transport to the emergency department. In the United Kingdom, conveyance rates have decreased from 58% to 90% over the past decade, and this has been associated with the development of community paramedic programs.41 Community paramedic programs appear safe, with better patient outcomes for certain populations.42,43 We will review examples of such programs, focusing on care provision for older adults. One community paramedic program that specifically addresses the needs of long-term care (LTC) residents is the extended-care paramedic (ECP) program in Halifax, Nova Scotia.44 LTC residents represent a unique group of ED attendees who often have worse health outcomes. The ECP program was initiated in February 2011. Seven experienced, advanced-care paramedics were provided additional training on extended-care roles, including geriatric assessment, end-of-life care, primary wound closure techniques, and point-of-care (bedside) testing.44 ECPs work alone in nontransport-capable vehicles that respond to predesignated LTC facilities within the region. The goal of the program is to provide care on site with medical direction (emergency and LTC physician advisors). Disposition for ECP patients includes treat and release, facilitated transport (e.g., transport for x-ray, with return to residence), or immediate emergent transport. This type of program spans the entire spectrum of care, including the before, during, and after stages. The ECP-LTC program provides care in nursing homes, but also aims to facilitate transfer to the ED for diagnostics and treatment when necessary. In some cases, it can help with discharge in that follow-up care will be provided that is typically not available in the LTC setting or can take time to implement. There have been a number of important attributes to the program that may improve emergency care provision in this setting. ECP responses involve more collaboration among LTC facility staff (physicians, nurses), patients, and families,45 thus promoting better communication among these groups during a health crisis. Another important aspect of this program was the identification of the role that ECPs could play in end-of-life care,45 during which patients could be provided with comfort care in their own residence, negating the need for transport if that was the ultimate goal of the patient. In the ECP cohort, 70% of patients enrolled in the study were treated in the residence, with 24% being facilitated transport and 6% urgent transport to the ED, compared to an 80% transport rate for traditional EMS during the time frame.44 Whether such a program is adaptable to other settings requires further investigation. EMS referral programs are being established as an alternative to ED transport or what is known as treat and release. Referral programs aim to identify safe alternatives to ED transport for those with less urgent conditions. However, there is controversy over whether paramedics can determine medical necessity.46 Referral programs have been successful for specific conditions. For example, referrals to falls teams have demonstrated positive results for high-risk patients.47 In this program, the referral was generated following the response by administrative staff. Community referrals by EMS (CREMS), based in Toronto, Canada, was launched in 2006 (Solutions East Toronto Health Collaborative) with the goal to make efficient use of resources and generate referrals to community-based care. These services require more rigorous evaluation. Paramedics were traditionally not points of referral, but this is changing. Other models aim to evaluate decision support systems for referrals.48,49 Vicente and colleagues have investigated a decision support system to determine whether frail older adults with certain complaints can be safely referred to geriatric services.49 Another example is the paramedic pathfinder.48 This is an algorithmic approach to decision making based on symptom discriminators from the local triage system. Two pathways have been created for use by ground ambulance paramedics; these include the trauma and medical pathways.48 These systems use symptom-related findings rather than diagnostics to discern disposition, with acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity observed.48 In the United Kingdom, paramedics have expanded their assessment, triage, and treatment skills to manage the growing demand for paramedic services. The emergency care practitioner (ECP) model involves having a paramedic or nurse respond in nontransport-capable vehicles to provide care to patients in their own home. Services were initially established to provide care to older adults with seemingly minor complaints.50 If necessary, paramedics can facilitate transport to the ED for diagnostics. Education typically entails an brief period of intensive specialized training (3 weeks) focused on obtaining histories, physical assessments, and ordering diagnostics. A portion of the training is also spent in supervised practice. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the paramedic practitioner model, those treated by paramedic practitioners were less likely to have attended an ED during the initial episode or in the next 28 days. Patients were also less likely to require a hospital admission and were more likely to report that they were very satisfied with their care.29,42 The authors concluded that the service reduced resource use (ED conveyance) and appeared safe.51 The emergency care practitioner’s role can have varying effects that are dependent on the setting in which they are deployed.52 The role should be used to supplement existing roles rather than replacing existing services. The goal of community paramedic programs is to reduce emergency department visits while also providing safe and effective care that is in accord with the patient’s wishes. These models might ensure that frail older adults get the care that they need by the right provider in the right place; however, more research is required to understand the role of these services.

Geriatric Emergency and Prehospital Care

Emergency Medicine in Context

Paramedical Services

Epidemiology of Emergency Department and Paramedical Services Use

Frailty in Acute Care

New Approaches to Geriatrics in Paramedical Services and the Emergency Department

Paramedical Service Care before the Emergency Department

Accessing Emergency Services: Communications and Dispatch

Secondary Telephone Triage

Traditional Paramedical Services

Community Paramedicine: Nontraditional Paramedical Services

Extended-Care Paramedic Program

Collaboration with Primary Care (Referral Services)

Emergency Care Practitioner Model

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Geriatric Emergency and Prehospital Care

117