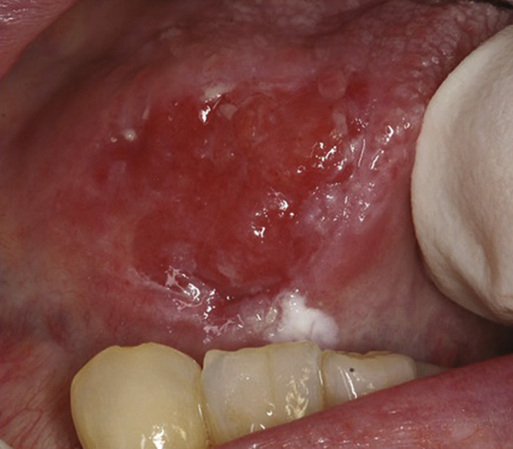

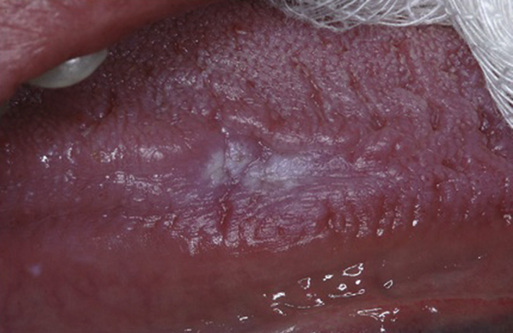

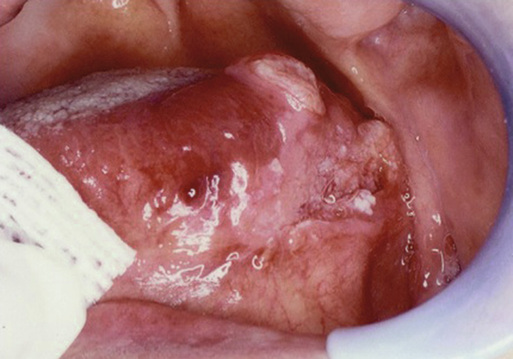

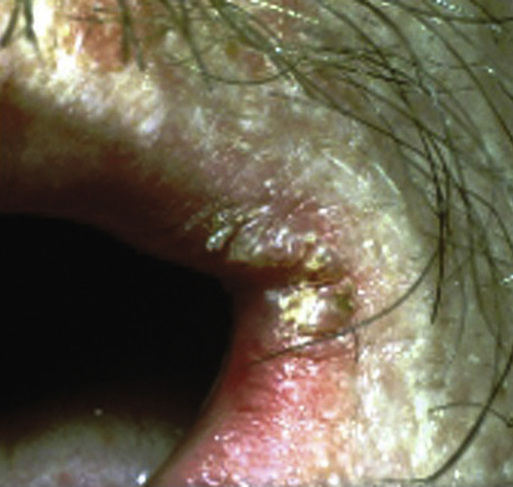

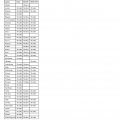

Andrea Schreiber, Lena Alsabban, Terry Fulmer, Robert Glickman Whereas dental textbooks address the management of medically compromised older patients—generally including a review of the basic pathophysiology of a disease, clinical signs and symptoms of the condition, common therapeutic interventions, and how the disease itself or the medications for it might affect planned dental care—in general, medical textbooks, even those on geriatric medicine, do not address the impact of oral health on the overall systemic health of a patient. Physicians are uniquely situated to screen older patients for common oral diseases. Older adults tend to have low use rates of dental services, due perhaps to a lack of insurance coverage for these services or limited access to care secondary to infirmity. Although more than 90% of adults older than 75 years seek medical care on a regular basis, only approximately one third of them seek dental care.1 In a pilot study2 investigating the physician’s role in the diagnosis and management of oral disease in a geriatric population, four primary care physicians and four geriatricians were asked to identify oral conditions on 30 color slides. The rate of correct diagnosis was 55%, and appropriate treatment decisions were made 70% of the time. In another study3 performed to assess hospital physician knowledge and views concerning oral health in older patients, 70 respondents completed a survey and were asked to diagnose 12 different oral conditions demonstrated on clinical slides. Although 84% of respondents thought that it was important to examine the oral cavity, only 19% reported that they did so. Of the responding physicians, 56% did not feel confident in examining the oral cavity and 77% thought that that they had insufficient training to do so. Of the 70 physicians, only 2 (3%) were able to identify all 12 oral conditions depicted in the slides correctly. The focus of this chapter will be on the maintenance of oral health for the geriatric patient and how physicians and dentists can ensure that this goal is attained. Topics to be discussed include the definition of oral health, how oral health is measured, changing dental needs of the geriatric population due to advances in medicine and dentistry, impact of oral health on systemic health, recognition and management of common oral conditions in older adults, and access to care issues for community-dwelling older adults and residents of long-term care facilities. Prevention and management of oral disease will improve systemic and oral health.4 Any discussion concerning the maintenance of oral health as a goal must start with a definition of the term.5 Mouradian6 defined it as “…encompassing all of the immunologic, sensory, neuromuscular and structural functions of the mouth and craniofacial complex. Oral health influences and is related to nutrition and growth, pulmonary health, speech production, communication, self-image and societal functioning.” Although Mouradian was addressing the oral health needs of the pediatric population, this definition of oral health seems to apply to the population in general and to the geriatric population in particular. Conditions that adversely affect the oral and maxillofacial complex are common and pervasive in older adults and can affect an individual’s general health and quality of life. Common measures of oral health include the number of teeth present in the mouth, presence of caries (Figure 110-1) and restorations, and presence or absence of periodontal disease (infection of the gingiva and tooth-supporting structures; Figure 110-2) and oral mucosal lesions (Figures 110-3 through 110-6). Many attempts have been made to quantify the effect of these parameters on oral function and relationship of adequate oral function to an individual’s quality of life. In a literature review7 focused on determining the relationship between dentition and oral function, four specific areas were investigated—overall masticatory function, aesthetics and psychosocial ability, posterior dental occlusal stability and support, and other functions, including taste and phonetics. In this study, 83 articles met inclusion criteria for review. Satisfactory masticatory function was linked to the total number of teeth present—specifically, 20 teeth with 9 or 10 dental contacts (upper and lower teeth in occlusion). Patients with fewer teeth and/or fewer contacts demonstrated limited masticatory function. Dental aesthetics and psychosocial satisfaction were linked to the loss of anterior teeth with variations in satisfaction noted among age groups, cultures, and socioeconomic status. Occlusal stability was noted with three to four posterior units in individuals with a symmetric pattern of tooth loss and five to six posterior units in those with a nonsymmetric pattern of bone loss. Patients did not attribute a high value to phonetics or taste. The conclusion of the authors was that the World Health Organization’s goal of maintaining 20 natural teeth throughout life as a means of ensuring an acceptable level of oral function is supported by current literature. Measures of oral health-related quality of life (OH-QoL) assume functional and psychosocial impacts on the quality of life but exactly what is being measured by a variety of instruments designed for this purpose still remains to be clearly elucidated.8 Many efforts have been underway to verify the validity of the QoL assessment tools used to measure the impact of oral health on QoL or to add subscales to current tools to aid in quantifying a qualitative question.9,10 In a survey investigating the association among tooth loss, chewing ability, and association with oral and general health-related QoL issues, two survey instruments were used, the Oral Health Impact Profile and EuroQoL Visual Analogue Scale. In addition to the patient survey, functional tooth units were assessed by calibrated dentists on more than 700 Australians older than 50 years. The number of functional tooth units was positively related to chewing ability and general health, thereby reflecting the importance of oral health to general well-being.11 The aim of the Ontario Study of Oral Health of Older Adults (OSOHOA) was to document the natural history of oral diseases and disorders in older adults and to document the impact on physical, functional, and psychological well-being.12 This was an observational cohort study of a random sample of adults who were older than 50 years when recruited. The study consisted of a baseline phase and 3- and 7-year follow-ups. The ability to chew was assessed using an index of six different foods. Descriptive statistics were used to measure changes in chewing ability over time. The proportion of individuals experiencing increased chewing problems rose from 24% at baseline to 33.8% over the 7-year period. An increased prevalence and severity of chewing dysfunction was most notable for edentulous patients. Other studies have noted that approximately one third of older adults have trouble biting some foods and that this percentage increases with advancing age and number of teeth missing.13 Chewing ability or lack thereof can influence food choices and result in malnutrition in community dwelling and long-term care residents (Figure 110-7). Weight loss and poor nutrition in long-term care facilities have been linked to chewing problems.14,15 Advances in dental research have resulted in a lower incidence of tooth loss and caries in the general population as a result of the widespread use of fluoride, patient education, and dental hygiene programs.16 Simply put, people are living longer with more teeth. The fully edentulous octogenarian is and will continue to be less frequently encountered in the twenty-first century. However, edentulous patients, despite the absence of teeth, may have a host of problems that can adversely affect oral and systemic health, including denture or non–denture-related soft tissue lesions, oral candidiasis, malnutrition from ill-fitting dentures (Figure 110-8) or lack of thereof, resorption under existing dentures (Figure 110-9), gastrointestinal problems, masticatory insufficiency, swallowing disorders, and aspiration pneumonia. They are still susceptible to mucosal diseases (see Figures 110-3 and 110-4) and oral cancers (see Figures 110-5 and 110-6), despite the absence of teeth. The Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health in America in 2000 cited 30,000 new diagnoses of oral cancer each year, mainly in individuals with a median age in the sixth decade of life.17 The types of problems encountered by a dentate or partially edentulous geriatric patient may include dental caries, chronic facial pain and/or temporomandibular dysfunction, and benign or malignant lesions of the oral mucosa or jaws. Periodontal disease, an inflammatory disorder that results in alveolar bone loss and chronic tissue inflammation (Figure 110-10), is a primary cause of tooth loss in older adults, which has been shown to have a strong association with the pathophysiology of certain systemic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), and diabetes mellitus.18 Patients with periodontal disease are up to twice as likely to develop cardiovascular disease.19 Medications taken for comorbid conditions may result in decreased salivary flow, which in turn affects the ability to chew, swallow, and cleanse the oral cavity. Additionally, xerostomia may be accompanied by painful or burning sensations. Finally, maxillofacial trauma as a result of gait disturbance, neuromuscular disease or, in some cases, elder abuse, is another factor affecting the oral health of the geriatric population.5 As advances in medical research result in increasing patient life span, older adults have become the fastest growing portion of the population. In the United States, population projections indicate that by the year 2030 more than 20% of the population will be 65 years of age or older.20 Because concurrent advances in dental research have resulted in less tooth loss in older adults, these patients will require an increased need for dental care in the future, most especially with the advent of dental implants leading to less reliance on conventional dentures as a primary form of treatment. Although the trend is toward less tooth loss in older adults, there are still regional demographic variations, with higher levels of edentulism in areas of lower socioeconomic status. With increased tooth retention comes the continued risk of recurrent and cervical caries. The pattern of caries differs in the geriatric versus the general population in that coronal (chewing surface) caries are less frequent than root caries. Root or cervical caries (Figure 110-11) are characterized by rapid progression and increased difficulty in restoration, often necessitating extraction (see Figure 110-1).20,21 Dentists are now challenged with treating an increasing number of community-dwelling older adults with chronic but stable systemic diseases, along with caring for the dental needs of more debilitated and frail older adults, with physiologic and cognitive impairments. According to the Surgeon General’s report in 2000, more than 20% of home-bound or institutionalized older adults require emergency dental care annually. As this population increases, so too will the need for care.17 The well-established links between oral and systemic diseases have served as a wake-up call to improve oral hygiene and access to dental care for older patients in long-term care facilities.22,23 One such risk is aspiration pneumonia, which has long been recognized as a common cause of death in infirm homebound and long-term care facility residents. Bacterial pneumonia is directly linked to aspiration as a result of dysphagia and/or poor oral hygiene and the elevated numbers of respiratory pathogens in oropharyngeal secretions. Attention to improved oral hygiene is a method or strategy to decrease the incidence of bacterial pneumonia in susceptible populations.24 The main causes of community-acquired pneumonia are Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. The organisms usually associated with hospital-acquired pneumonia are Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Hospital-acquired pneumonia commonly occurs in frail older adults with a compromised immune system. Aspiration is most likely to occur in patients with functional dependence on oral care and feeding.25,26 Studies have demonstrated increased levels of bacteria in the oral secretions of institutionalized versus home-dwelling older adults.27 Aspiration usually occurs with feeding or during sleep. The risk of developing an infection subsequent to aspiration depends on the state of the individual’s host defenses—cough reflex, mucociliary adequacy, and cellular immunity—and on the type and volume of aspirate. The higher the bacterial load of the aspirate and the lower the host defenses, the greater the risk.28 Oral care for functionally dependent older patients in long-term care facilities has been documented as being sorely lacking in numerous studies.29,30 Poor oral hygiene leads to the proliferation of dental plaque, which is a biofilm responsible for dental and periodontal disease (see Figure 110-2). As the biofilm matures, organism shedding is facilitated. Reduced salivary flow in older adults as a consequence of medications, aging, or disease may also enhance microbial growth in the oral cavity. Similarly, long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotics may contribute to the overgrowth of certain organisms in the oral cavity. A study by Adachi and colleagues31 investigated the incidence of fever higher than 37.8° C and aspiration pneumonia in the residents of two nursing homes for 2 years. Patients who received professional oral health care were compared with patients who did not. The prevalence of fevers and rate of aspiration pneumonia were significantly lower in the patient group that received professional oral health care than in the group that did not. It has been demonstrated that improved oral hygiene efforts in long-term care facilities result in a decreased incidence of fevers and pneumonia deaths. Effects of improved oral health care on other systemic diseases, such as cerebrovascular accident, diabetes mellitus, and myocardial infarction, have yet to be fully investigated. Desvarieux and associates32 have investigated the relationship between periodontal disease and tooth loss with subclinical atherosclerosis. Subjects received comprehensive periodontal examination, a carotid scan, and evaluation of cardiovascular disease risk factors. A significant association was noted between observed prevalence of carotid plaque formation and the number of teeth missing. Approximately 60% of individuals missing more than 10 teeth demonstrated carotid artery plaque, and this association was greatest among patients older than 65 years. The mechanisms underlying the relationship between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease are not well understood but are likely due to chronic bacteremia and elevated inflammatory markers. Interestingly, in a follow-up study, gender variations were noted in the relationship between periodontal disease, tooth loss, and subclinical atherosclerosis, with men being affected more frequently than women.33 The relationship between cardiovascular disease and stroke and periodontal disease has been the object of numerous studies in the last decade, with most focusing on the role of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin, and tumor necrosis factor. Periodontal disease results in elevations of CRP and interleukin levels, but a clear link between periodontal disease and the pathogenesis has yet to be elucidated. Studies have been conducted to explore the possible link between periodontal health and cardiovascular disease. Bartova and coworkers have concluded that circulating microorganisms or their products may promote pathogenesis and enhance local inflammatory changes in vessel walls leading to clotting and clot formation, a potential risk factor for atherosclerosis development.34 Kalburgi and colleagues noted that periodontitis may cause systemic changes in plasma levels of CRP and numbers of circulating leukocytes and neutrophils. CRP, leukocyte, and neutrophil levels have been positively correlated with the severity of periodontitis. Thus, periodontitis, a common chronic condition, may predispose affected patients to CVD by increasing the levels of systemic markers of inflammation, which may contribute to the development of atherosclerosis.35 The therapeutic implications for such an association are significant, given the prevalence of periodontal disease in the general population and the relative ease with which oral hygiene improvement can be accomplished. Other risk factors for the development of CVD, such as gender, hypertension, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, are less readily addressed and modified. Animal studies have indicated that chronic infections lead to increased systemic inflammation and the accelerated development of atherosclerotic plaque.36 The results of the meta-analysis of five prospective cohort studies involving more than 85,000 patients have indicated that patients with periodontal disease had a 1.14 times higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease than patients without periodontal disease. The highest risk (1.24) was assigned to individuals with fewer than 10 remaining teeth. A meta-analysis of five case-control studies involving more than 1400 individuals demonstrated an even higher risk of individuals with periodontal disease developing CVD.37 Several studies have been conducted to determine whether there is a relationship among periodontal disease, treatment, and diabetic control. Although some results were optimistic, Engebretson and associates found that nonsurgical periodontal therapy did not improve glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate to advanced chronic periodontitis. Thus, nonsurgical periodontal treatment in patients with diabetes for the purpose of lowering levels of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) cannot be supported at this time.38

Geriatric Dentistry

Maintaining Oral Health in the Geriatric Population

Introduction

Definition of Oral Health

Measures of Oral Health and Function

Changing Need for Dental Care in Geriatric Patients

Oral Health Impact on Systemic Health

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Geriatric Dentistry

110