2.1 Failure to Thrive

2.1.1 Name of Disorder

Failure to thrive (FTT).

2.1.2 Clinical Definition

Inadequate growth, weight gain, or weight for height.

2.1.3 How It Is Diagnosed

Weight for age <3rd percentile or crossing over 2 percentile lines on the growth chart or < 80% of ideal body weight for age.

2.1.4 Nutritional Implications

Poor weight gain in childhood is often secondary to poor caloric intake. Long term, this can lead to cognitive defects and stunting.

2.1.5 Pearls

- It is important to distinguish between FTT caused by disease states such as celiac or renal tubular acidosis and FTT caused by poor caloric intake.

- Workup should be guided by physical examination findings as well as medical history.

- Most outpatient FTT in an asymptomatic child is secondary to poor caloric intake as a result of food refusal or excessive juice/water intake.

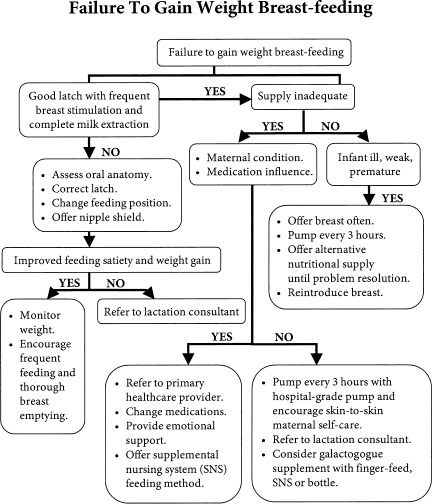

Nutritional Algorithm for Failure to Gain Weight Breast-Feeding

2.2 Failure to Gain Weight Breast-Feeding

2.2.1 Name of Disorder

Failure to gain weight Breast-Feeding.

2.2.2 How It Is Diagnosed

Weight loss, lethargy, fussiness, low urine and stool output, and lack of satiety after feeding.

2.2.3 Nutritional Implications

Factors that interfere with successful breast-feeding include maternal health, maternal medications, health of infant, frequency of breast stimulation, poor sucking, and incomplete extraction of milk from breasts.

2.2.4 Pearls

- Supplementing with a bottle (and thus infrequent breast stimulation) is the most common cause of loss of milk supply.

- Infant oral motor disorders and maternal condition are rare causes of failure to gain weight but must be considered as part of evaluation.

- Proper latch, frequent suckling, and complete breast emptying are keys to successful breast-feeding.

- Bottle supplementation of healthy mothers and newborns is most often due to lack of confidence in mothering skills, lack of knowledge, and lack of support.

In 2005 the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published its revised policy statement on breast-feeding. In it, the AAP supports exclusive breast-feeding for healthy infants and provides recommendations for physicians and other health care professionals. To support new parents, we must first understand the lactating breast and the important role the infant plays in this mother–infant dance.

2.2.5 Overview of Lactation

Lactogenesis is the process by which the mammary gland develops the capacity to secrete milk. The process begins midpregnancy and continues after delivery with the onset of milk secretion (lactation). After delivery of the placenta, progesterone levels fall quickly, allowing for a rapid onset of milk secretion within 30 to 40 hours of delivery (engorgement). This phase is independent of milk removal. However, ongoing successful milk production is highly dependent on continual and effective milk removal as defined by frequency, duration, and efficiency of infant suckling and/or maternal expression/pumping. Suckling stimulates the anterior pituitary gland to secrete prolactin, which triggers breast alveoli to secrete milk and the posterior pituitary gland to secrete oxytocin. In turn, this stimulates the breast alveoli to eject milk (“let-down”) into the ducts. The breast begins to return to its prepregnant state (involution) when there is mechanical pressure from the distended gland, together with cessation of stimulation of the gland. Milk stasis, together with the whey protein called feedback inhibitor of lactation (FIL), is believed to set up a cascade of actions that down-regulate milk synthesis.

2.2.6 Supply

Adequacy of milk supply is highly dependent on frequency, duration, and effective suckling/expression. Although breast size may vary widely in the lactating woman, milk supply at various points over time is fairly consistent. Small-breasted woman are capable of producing just as adequate volumes of milk for their infant as a large – breasted woman; however, they may have a smaller storage capacity and may need to feed more frequently. The following is a guideline for volumes produced.

| Type of Milk | Time Range Expected | Quantity |

| Colostrum | In the first 24–48 hours | 10–100 mL/day Average: 30 mL/day |

| Mature milk | By 36 hours By 72 hours By 3–4 weeks | ∼50 mL/day 500–600 mL/day 700–800 mL/day |

Breast-feeding is not fully established until 3–4 weeks after delivery. Introducing alternative feeding methods such as a bottle for convenience only undermines supply. The number of times an infant feeds in 24 hours depends on a number of factors, but in the early days to weeks of life, feeding 10 to 12×/day is not uncommon. True inadequate supply in a healthy newborn is not as common as a perceived inadequate supply. This happens when the parents misinterpret the infant’s cues of short sleep times, fussiness, and frequent feedings as a sign that the mother is not producing enough milk, and thus parents supplement with cow’s milk. Discussing feeding frequency of a breast-versus-formula-fed infant, satiety after feeds, stool and urine output, nutritive versus nonnutritive sucking needs, and weight gain can give parents the tools to assess their infant adequately and boost their confidence as new parents.

- Galactagogues are drugs/supplements that may have some effect on increasing milk supply. The most common of these are metoclopramide and domperidone. Their antidopaminergic effect is thought to elevate the release of prolactin and increase milk synthesis. Domperidone has been linked to arrhythmias and is not easily available in the United States for this off-label use. The off-label use of metoclopramide must be used with caution due to the potential side effects of depression and the extrapyramidal symptoms.

- Women take many herbal supplements to increase milk synthesis, the most common of which is fenugreek. Although it is frequently used and many women report an increase in milk synthesis, very little evidence or science supports its use. Reported side effects with its use are hypoglycemia (contraindicated in women with diabetes, asthma, or peanut allergies), and it may make the woman’s and baby’s urine smell like maple syrup.

- Methods to supplement breast-feeding usually involve a bottle. If a bottle must be used and the goal is eventual breast-feeding, then a bottle with a slow-flow nipple should be chosen. This provides infants with a similar experience at the breast in that they must suck to extract or transfer the milk. Many nipples simply allow the milk to drip out into the infants’ mouths, and all that infants then need to do is to swallow what is in their mouths.

- A supplemental nursing system (SNS) is a commercially available unit that is another option to mothers with low milk supply. It promotes suckling (thus increasing milk synthesis) while providing the infant with milk from the breast and supplementation at the same time. A bottle of milk with two small tubes is placed on the mother. The tubes are taped to her breasts. The infant is latched to both the tube and the breast, receiving what is in the mother’s breasts and the supplement in the bottle. It also provides breast stimulation to increase milk synthesis.

- Finger feeding is a method to administer milk orally to an infant without the use of a bottle. Finger feeding involves taping a small 5 or 6F feeding tube to a parent’s finger. Connected to the feeding tube is a syringe full of milk (10 cc is best). As the parent allows the infant to suck on their finger, milk is slowly administered from the syringe as the infant sucks.

- Another method used in some nurseries is cup feeding, in which infants are presented with a small medicine cup of milk and allowed to “lap” it up into their mouths. This method can often waste milk and makes quantifying intake difficult.

2.2.7 Latch and Suck

The goal of latching onto the breast is adequate milk removal or “milk transfer.” Simply having the mouth to the nipple is inadequate for milk transfer. Frequent suckling is good to increase volume, but suckling without milk transfer will not increase supply. Therefore, it is imperative to success that adequate latching, sucking, and milk transfer be evaluated.

Milk transfer can often be assessed by observing the change in the baby’s sucking rhythm. Initially, after latching, the baby “flutter-sucks.” These are short sucks without swallowing that stimulate the mother’s let-down reflex. Once let-down has occurred, the infant’s sucking pattern should switch to long, rhythmic draws as milk is transferred and swallowing occurs. Flutter-sucking throughout a feeding indicates there is no milk being transferred, and although infants appear to be suckling, they will usually cry if removed from the breast and act as if they are still hungry (which they are).

Clinical Symptoms of a Poor/Incorrect Latch

Symptoms include pain throughout the feed (not transient discomfort), chomping or biting sensation, smacking or clicking sounds heard, observation of only rapid or flutter sucking, baby falls asleep right away or cries and never seems satiated.

Solutions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree