In a series of 400 patients older than 70 with cancer, Luciani et al. [37] studied the SOF (Study of Osteoporotic Fractures) index versus geriatric assessment including 7 questionnaires. Geriatric assessment included CIRS-G, number of medications, ADL, IADL, MMSE, social status assessment and MNA thus omitting evaluation of mood. Risk of falls was not included in geriatric assessment (as endpoint) but SOF has been demonstrated to predict risk of falls and fractures. Abnormal gold standard was defined as one or more abnormal domains. The SOF index includes three components (5 % or more weight loss during the preceding year, inability to rise from a chair five times without using the arms, negative answer to the question “Do you feel full of energy?”). The index is considered positive if two or more of the three components are present. Overall, 68.2 % of patients were classified as unfit according to geriatric assessment and 67.8 % according to SOF. Sensitivity and specificity of SOF were respectively 89 % (95 % confidence interval (CI): 84.7–92.5) and 81.1 % (95 % CI: 73.2–87.5).

In a large series of 259 patients older than 70 with mainly breast and digestive tract cancer, Biganzoli et al. [38] tested two tools, VES13 and CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study). CHS includes the study of five parameters: unintentional weight loss in the past year, self-reported exhaustion, weakness (grip strength), slow walking speed and low physical activity. Patients are considered frail if they have three or more abnormalities, pre-frail if they have one or two and fit if all CHS parameters are normal. CGA included CIRS-G, ADL, IADL, MMSE, GDS and MNA. Risk of falls was not studied. The CGA was considered impaired in the presence of abnormal results in ≥1 domain. Finally, 47, 75 and 66 % were considered impaired according to VES13, CHS and CGA respectively. Sensitivity and specificity of CHS were respectively 87 and 49 % versus 62 and 81 % for VES13. Great variability in specificity of CHS was observed within subgroups.

The G8 questionnaire (Table 15.2) has been developed for the purpose of screening for cancer treatment in a prospective series of 364 consecutive patients with various types of cancer including lymphoma (110 patients) [39]. A cut-off value of 14 provided a good sensitivity estimate (85 %) without deteriorating specificity (65 %). To validate this questionnaire, we launched the Oncodage study in 23 geriatric oncology centers in France [36] (see above). Overall, 1,688 patients have been accrued and 1,435 were eligible and evaluable. Sensitivity was 76.5 % and specificity 64.4 %. The reliability of the questionnaire was good with a kappa coefficient of 0.64 (95%CI: 0.61–0.70). The time required to complete the questionnaire was, on average, 4.4 min (± 2.8) and 98.7 % completed it in less than 10 min. Multivariate analysis showed that, together with sex, stage and performance status, G8 was predictive of one-year survival. Another study including 937 prospective patients with various types of cancer including hematological malignancies, confirmed the strong prognostic value of the G8 questionnaire [40]. Geriatric assessment included living alone, ADL, IADL, MMSE, GDS-15, MNA score and presence of at least one comorbidity on the Charlson comorbidity index (risk of falls omitted) and abnormality defined as two or more abnormal questionnaires. G8 was evaluated as a screening tool and showed 86.5 % sensitivity and 59.3 % specificity. fTRST (Flemish version of the Triage Risk Screening Tool) was also proposed for screening. Sensitivity was 91.3 % and specificity was 41.9 % with a threshold for abnormality defined as ≥1.

Items | Possible answers (score) | |

|---|---|---|

A. | Has food intake declined over the past 3 months due to loss of appetite, digestive problems, chewing or swallowing difficulties? | 0: Severe decrease in food intake |

1: Moderate decrease in food intake | ||

2: No decrease in food intake | ||

B. | Weight loss during the last 3 months | 0: Weight loss >3 kg |

1: Does not know | ||

2: Weight loss between 1 and 3 kg | ||

3: No weight loss | ||

C. | Mobility | 0: Bed or chair bound |

1: Able to get out of bed/chair but does not go out | ||

2: Goes out | ||

E. | Neuropsychological problems | 0: Severe dementia or depression |

1: Mild dementia or depression | ||

2: No psychological problems | ||

F. | Body Mass Index (BMI (weight in kg)/(height in month [2]) | 0: BMI < 19 |

1: BMI = 19 to BMI <21 | ||

2: BMI = 21 to BMI < 23 | ||

3: BMI = 23 and >23 | ||

H | Takes more than 3 medications per day | 0: Yes |

1: No | ||

P | In comparison with other people of the same age, how does the patient consider his/her health status? | 0: Not as good |

0.5: Does not know | ||

1: As good | ||

2: Better | ||

Age | 0: >85 | |

1: 80–85 | ||

2: <80 | ||

Total score | 0–17 |

Overall, definition of abnormal CGA was based on various combinations of questionnaires and evaluations leading to a proportion of frail patients of 30 [35] to 94 % [39]. Furthermore, all series focused on a number of abnormal questionnaires as a target although outcome measures would be much preferable. Considering the screening test, the proportion of frail patients varied from 47 [38] to 82 % [39]. It appears that these proportions highly depend on the characteristics of the population screened which highly varies from one study to the other.

Additional tools are available, such as the Barber Questionnaire that was developed as a screening procedure for older adults in general practice [41], but results reported for older adults with breast cancer are disappointing [42]. Further geriatric tools have been proposed for screening purposes such as the short CGA [43], the abbreviated (a)CGA [44], and the Groningen Frailty Index (GFI) [45]. However, overall, most of these instruments have only been presented in feasibility or pilot studies [46], and initial results suggest that they miss too many cases of vulnerable patients [47].

A recent systematic review [48] compared all available screening methods to CGA and reported a median sensitivity for the VES-13 of 68 % (range 39–88 %), and median specificity of 78 % (range 62–100 %) while corresponding results for G8 were 87 and 61 %. A task force has been recently launched by the SIOG (International Society of Geriatric Oncology) to systematically review currently available results on screening tools.

Once screened as frail, patients deserve further attention from their hematologist. CGA is the most obvious solution to propose. However, it may not be possible in all cancer centers depending on the availability of geriatricians. Consequently, other solutions should be considered. This includes increased medical attention from the hematologist such as thorough evaluation of comorbidities, precise evaluation of major functions such as renal and hepatic systems, consideration of nutritional, socio-economic, mood and cognitive conditions of the patients through the involvement of the health professionals of the supportive care team. Another proposal can be a two-step process including screening tool performed in the oncology setting, then a second step performed by geriatric teams, which can be the whole CGA or a specific geriatric tool that remains to be developed. This may be also the evaluation of the patient by a geriatrician which may lead to further intervention to correct identified impairments. Yet, the impact of geriatric intervention in cancer patients is not yet demonstrated. One randomized trial showed significant improvement of survival with home care intervention performed by advanced practice nurses [49] but only in an unplanned sub-analysis on patients with advanced stages of cancer. Further trials showed some benefits of interventions (more appropriate management [50], quality of life [51, 52], physical functioning [51, 53–55]) but there was no reported impact on survival. Furthermore, some of these studies were not exclusively focused on older patients [53, 55]. Finally, the validity of geriatric intervention is not demonstrated up to now and our community should perform randomized controlled trials in the near future to solve this question.

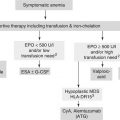

Selection Process in Hematological Malignancies

Overall, it is now possible to foresee what should be the selection procedure to identify frail patients before treatment of hematological malignancies. However, the whole procedure has to be adapted to the hematology setting. Indeed, when the disease can be cured, even with attenuated treatment, it is not possible to decide whether treatment will be palliative or curative based on a screening test, whatever its performances. The question is particularly tricky in the unfit elderly. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is such a disease. Some series have already proposed to select patients with geriatric assessment. Tucci et al. selected patients with four parameters: age, ADL, CIRS-G and occurrence of geriatric syndromes in a prospective series of 84 evaluable patients [8]. This procedure was blinded to the physicians who classified patients as fit or unfit on usual criteria. Indeed, geriatric criteria appeared more efficient to predict prognosis than physician evaluation.

A few prospective trials have been proposed in a search for optimal treatment for frail patients. In the EORTC 20992 phase II trial [56], we proposed to vulnerable/frail patients a cautious strategy including the well-known COP regimen with its low toxicity profile, specific chemotherapy dose adaptations and geriatric assessment. Among 32 registered patients, 27 were evaluable for efficacy and toxicity. Main characteristics of the patients are outlined in Table 15.3. As expected, results were poor with quite a low response rate, short median survival, but also, despite all precautions, four severe toxicities (three toxic deaths and one febrile neutropenia) (Table 15.3) leading to early termination of the trial. Yet specific precautions were proposed to reduce toxicity including upfront dose reductions based on baseline blood counts, creatinine clearance and performance status. Furthermore, chemotherapy doses were reduced during treatment (and maintained thereafter as already performed in another elderly-specific trial [57]) according to specific toxicities including, among others, febrile neutropenia, but also significant weight loss and degradation of autonomy. These precautions were efficient since only seven patients experienced grade 3 or 4 neutropenia (22 %). However, as observed in the retrospective series of Thieblemont et al. [58], three of them experienced febrile neutropenia and two died thus highlighting again the real frailty of these patients. Finally, geriatric evaluation data showed the specificity of the selected population with 53 % ADL-dependent, 81 % IADL-dependent, 94 % high GDS15 (≥6), 37.5 % MMS < 24.

Table 15.3

Comparison of unfit patients as selected by two different approaches

Italian trial [59] | EORTC trial [56] | |

|---|---|---|

Number of patients | 30 | 32 |

Median age (range) | 83 (70–96) | 78.5 (70–92) |

>80 years old | 73 % | 34.5 % |

PS 2–4 | 60 % | 69 % |

Geriatric assessment | ||

Older than 80 | 73 % | 34.3 % |

Dependent in one ADL or more | 56 % | 53 % |

Severe comorbidities | 43 % | 18.7 % |

Lymphoma characteristics | ||

Stage III or IV | 56.5 % | 50 % |

Elevated LDH | 46.5 % | 66 % |

aaIPI 2–3 | 56.5 % | 72 % |

International Prognostic Index (IPI) | ||

Age–adjusted IPI | 56.7 % | 72 % |

Performance status 2–4 | 60 % | 69 % |

Stage III or IV | 56.6 % | 50 % |

Elevated LDH | 46.7 % | 66 % |

Treatment results | ||

Neutropenia grade 3/4 | 13.3 % | 22 % |

Toxic deaths | 3 | 3 |

Overall response rate | 40 % | 44.5 % |

Complete response rate | 10 % | 18.5 % |

Median survival | 10 months | 10.1 months |

In a prospective trial of 30 patients, Monfardini proposed a cautious treatment with vinorelbine and prednisone at reduced doses [59]. In a population of patients with adverse features (Table 15.2), again, outcome was poor with 10 % complete response rate and 10 months median overall survival. Although toxicity profile appeared quite favorable with only 13.3 % grade 3 and 4 neutropenia, 3 toxic deaths occurred because of cardiac failure (Table 15.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree