Direct toxic substances

Bacterial and fungal toxins

Meal leftovers or “fast food”

Coffee

Excess

Glutamate

Chinese food

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

Grilled meat and vegetables

Heavy metals

Big fish, lead-covered pipes, glasses

Pharmacologically active compounds

Histamine

Cheese, white wine, tuna, and salmon

Tyramine

Chocolate, cheese, red wine

Sulfites

Wine

Immune mechanisms

IgE allergy mechanisms

IgE-mediated mast cell reactions

IgG-mediated food hypersensitivity

Excess of similar food active antigens in weekly diet (caseins, gluten, nickel compounds, etc.)

Celiac disease

Acquired antibodies to epithelial cells, negative IgE, villous damage – atrophy

Nonceliac gluten sensitivity

Excess submucosal lymphocytes

Genetics

Lactose nontolerant genotype

Lactase gene progressively switched off after weaning

Fructose nontolerant genotype

Rare mutation of the aldolase B gene

Some major genetic-based phenotypes are largely ignored by healthcare providers. Thirty percent of southern Europeans and a little less of northern Europeans are nonlactose tolerant. This percentage sums up to 80 % in Amerinds and 90 % of the Chinese Hun population. After weaning, like in all other mothers in these human phenotypes, the lactase gene progressively is switched off (Fig. 8.1). As a result of the lack of lactase, lactose cannot be split in its two composing sugars in the small intestine; as a cosequence, lactose acts either as an irritant molecule attracting fluids into the small intestine, determining immediate bowel emptying after consumption (subjects with chronic constipation that assume glasses of milk in the morning to evacuate thus making GI inflammation worse), or proceeds into the colon to feed otherwise marginal bacterial populations, which take advantage of lactose presence and produce hydrogen and finally cause the complex dysbiosis.

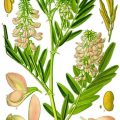

Fig. 8.1

Schematic representation of the typical switching of the lactase gene in mammalians. In some macro-ethnicities a relevant percentage of the population became lactose tolerant thanks to random mutations in the intron that allowed the polymerases to read the exon even in methylated gene. These random mutations are widespread among population that adopted cattle raising in the last 10,000 years. This allowed these lucky individuals to win the selective pressure given the advantage of being able to exploit cattle raising not only for meat but also for the reproducible rich source of protein, fat, and sugars provided by milk and dairy products. Unfortunately, this advantage is not universal among humans, and the introduction of dairy product in lactose-intolerant individual is a source of chronic disease

We also note rare inherited genetic carbohydrate intolerance (e.g., fructose intolerance, glucose or galactose intolerance) or protein intolerance (e.g., tryptophan intolerance or methionine intolerance) [25].

Celiac disease is considered as a separate nosological entity, but its paradigms and continuity with other immune-mediated gluten sensitivity are still under investigation (Fig. 8.2).

Fig. 8.2

Simplified criteria to identify the possible clinical conditions based on gluten interactions with the digestive system. Unfortunately the present selected wheat esaploid species are far more rich in gluten, up to 14 % net weight, than the ancestral tetraploid species

Approximately 2–8 % of children and 1–2 % of adults suffer from food allergies. Typically, nausea and vomiting are predominant symptoms if the site of allergy is in the upper gastrointestinal tract. The food allergens that most frequently trigger nausea and vomiting are those inducing the oral allergy syndrome consisting of swelling and reddening of the lips and the buccal, pharyngeal, and laryngeal mucosa. These allergens are most frequently the pollen-associated food allergens such as pipfruits, drupes, nuts [25], and shellfish.

8.5 Miscellaneous Causes of Nausea and Vomiting

Finally, additional causes of nausea and vomiting include acute pancreatitis, obstetric cholestasis, acute fatty liver of pregnancy and HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets) syndrome, as well as intestinal conditions such as appendicitis, and these apparently rare conditions need to be ruled out in the presence of a strong suspicion [19].

8.6 Gastroesophageal Reflux

The percentage of women who experience symptoms associated with GERD at any time during pregnancy range from 30 to 80 %, being highest in the third trimester [30]. The clinical features of pregnancy-associated GERD do not differ from those seen in the general population, with predominant symptoms being heartburn and regurgitation, that aggravate following meals and when lying in a supine position. For women already diagnosed with GERD prior to pregnancy, symptoms often worsen as pregnancy progresses [17]. There are a number of functional and structural alterations that occur at the gastroesophageal junction during pregnancy that may at least explain the high prevalence of reflux symptoms in this population. Reflux is due to a combination of factors that may be worsened in late pregnancy by the enlarging uterus, including an increase in gastric pressure, reduction in lower esophageal sphincter tone, decrease in gastric peristalsis, delayed gastric emptying, and a reduction in pyloric sphincter competence. Both estrogen and progesterone may relax the lower esophageal sphincter, which is also under the control of a variety of humoral agents including motilin, acetylcholine, noradrenaline, histamine, 5-HT, and prostaglandins [31].

Overall, available evidence indicates that H. pylori status does not have any effect on severity of or recurrence of symptoms in GERD, nor impact treatment efficacy, and that the eradication of H. pylori is not associated with development or exacerbation of GERD [32, 33]. Antacids taken before meals and at bedtime, together with the avoidance of late-night meals; excluding some foods, as chocolate; and sometimes raising the head of the bed, can help in controlling GERD symptoms. However, when a therapy is necessary, symptomatic treatments include alginate-based formulations, which create a foamy raft over the gastric walls, and do not account for adverse effects both for the mother and baby [34], and H2-receptor antagonists, as ranitidine, which are commonly used in pregnancy to control reflux symptoms and seem to have no adverse effects on the fetus [35]. Conversely, there are concerns about proton pump inhibitor use during pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, especially regarding the risk of asthma [36]. Generally speaking, H2-receptor antagonist and proton pump inhibitors use should be discouraged because they may alter the digestive functions of the stomach if assumed for several months in a row. When heartburns and reflux become evident, lifestyle changes should be encouraged as regards composition of meals (check for food hypersensitivity), time from meal to bedtime, and moderate exercise after eating.

8.7 Constipation

The reported prevalence of constipation in pregnant women varies between 11 and 38 % and occurs mostly during the second and third trimester, although symptoms can also be present since the 12th week of gestation [37] and last until 3 months after delivery [38, 39]. The pathophysiology of constipation is multifactorial and not yet well clarified but recognized primarily as a functional basis. Progressively rising progesterone and estrogen levels have been suggested as cause of constipation during pregnancy that inhibits gut smooth muscle function [40]. Other factors involved in pregnancy constipation are decreased colon motility, oral iron supplements, poor fluid intake as a consequence of nausea, and pressure on the rectosigmoid colon by the gravid uterus in the third trimester, as well as functional bowel disorders [41]. Management usually involves reassurance and advice about increasing fluid and fiber intake, while laxatives are rarely required [17].

Moreover, dietary supplements of fibers, as bran or wheat fiber, are likely to help pregnant women experiencing constipation [37]. Fiber intake is usually well below the standard recommendations in the daily health plate and thus is frequently forgotten by healthcare providers. Five to six hundred grams of vegetables and fruit per day is far above the common daily plate in most Western-style nutritional profile. No fiber means inadequate microbiota, possibly a critical immune cross talk with the intestinal immune system and low-grade inflammation, and decreased motility; for sure it means less hydrophilic stools, all summed up to create a chronic constipation, just made worse by pregnancy hormones and abdominal “mass.” Most women consider minor constipation and minor irritable colon a “normal condition” that just turns “unpleasant” in pregnancy, to be treated by drugs as it is common practice nowadays when doctors are confronted with lifestyle problems. Figure 8.3 could represent an interesting standard of counseling for women suffering from obstetrical constipation.

Fig. 8.3

The healthy eating plate as reported by the Harvard School of Nutrition considers that half of the daily plate is made up of veggies and fruits. A special note should include the additional concepts of “whole grains” (most of wheat products are now “refined”) and of “healthy proteins” that limit red meat, as in Mediterranean, Asian, and South American food pyramids, to one portion per week, far below the present nutritional profile in most countries where meat and meat products and derivates are part of each meal for each day

8.8 Probiotics in Pregnancy

Probiotics are defined as live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host [42]. Probiotics probably have at least two modes of action in improving constipation: firstly improving dysbiosis that is assumed to play a role in constipation [43, 44] and secondly lowering the colon pH by producing lactic, acetic, and other short-chain fatty acids and consequently enhancing colonic peristalsis and subsequently decreasing colonic transit time [43, 44]. Pilot studies have shown the beneficial use of probiotic mixtures for the treatment of constipation in pregnancy [39], as Ecologic®Relief (a mixture of Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, Bifidobacterium lactis W52, Bifidobacterium longum W108, Lactobacillus casei W79nn, Lactobacillus plantarum W62, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus W71) [39]. Probiotics might also reduce the risk of developing gestational diabetes [45]. In case of failure in resolving the constipation with both dietary supplements and probiotics, polyethylene glycol-based laxatives represent the ideal treatment for pregnant women [46] due to their very limited absorption.

8.9 Diarrhea

Together with the causes previously described for nausea and vomiting, irritable bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and enteric infection have to be considered in case of diarrhea appearing or worsening during pregnancy.

The incidence of gastrointestinal infections in pregnancy is not increased. Salmonella enteritidis and Campylobacter jejuni infections have been associated with fetal mortality due to the transplacental passage of microorganisms [47, 48]. Infection with Listeria monocytogenes is a well-recognized very rare cause of intrauterine infection and perinatal death. The infection is acquired through eating foods contaminated with the organism, and appropriate dietary advice should be given to all pregnant women about the avoidance of foods such as pâtés and soft and blue-veined cheese [19]. Pregnancy has little effect on symptoms associated with inflammatory bowel disease [17], but, similar to other chronic inflammatory conditions, most guidelines advise optimizing lifestyle during pregnancy, such as dietary changes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree