Fig. 28.1

Upper endoscopy of a stomach GIST (Courtesy of David Schwartz, MD, Vanderbilt University Medical Center)

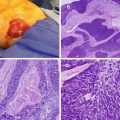

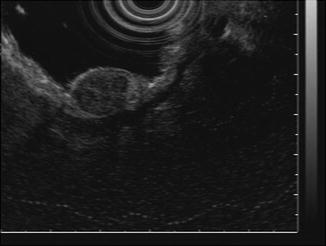

Fig. 28.2

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) of a stomach GIST (Courtesy of David Schwartz, MD, Vanderbilt University Medical Center)

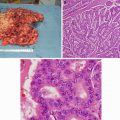

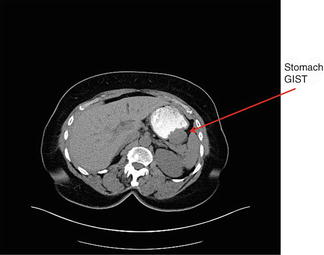

Fig. 28.3

CT of a stomach GIST (Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

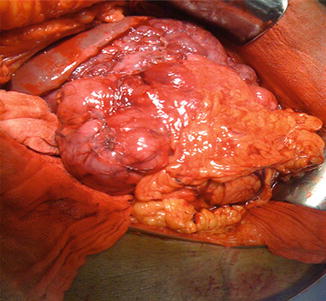

Fig. 28.4

Patient with a large stomach GIST (Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

CD-117 antigen by almost all (80–95 %) GISTs represented a major breakthrough in the classification, approach, and treatment of these tumors over the last 30 years [4]. Other spindle cell neoplasms arising in the GI tract such as lipomas, true leiomyomas, and leiomyosarcomas are typically CD-117 negative. The CD-117 molecule is part of the KIT receptor tyrosine kinase that is a product of the KIT proto-oncogene. This gene encodes a transmembrane receptor for a growth factor named stem cell factor (SCF). Binding of SCF to KIT induces KIT dimerization and activation. Constitutive activation of KIT signaling leads to uncontrolled cell proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis. The KIT product is expressed on the interstitial cells of Cajal, mast cells, and melanocytes, but a mesenchymal spindle cell tumor in the GI tract that stains diffusely positive for CD117 is characteristic of a GIST.

KIT mutations generally occur in one of four of the 21 exons of the gene. The most common mutation is of exon 11 which encodes for the intracellular component of the transmembrane portion, but mutations of exon 9 (the extracellular component of the transmembrane portion) are also common (7 %). Mutations of exon 13 and exon 17 are rare. Mutations make KIT function independent of activation, leading to a high rate of mitosis and genomic instability [5].

A small percentage of GISTs (5–7 %) have a mutation in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha (PDGFRA) instead of the more common KIT mutation [6]. PDGFRA is a receptor tyrosine kinase which shares extensive similarities with KIT, but the mutations are distinct in that they do not respond to the same growth factors. Almost all GISTs will harbor either the KIT or PDGFRA mutation, but not both since each is an alternative path to uncontrolled proliferation. As many as 60 % of PDGFRA mutations occur in exon 18 (specific mutation noted as D842V). Emerging data suggest that mutation type has important implications for prognosis, recurrence, response to therapy, and the development of tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance.

Diagnosis and Staging

GISTs originate from the interstitial cell of Cajal or its precursor, within the submucosa or muscularis propria, but may extend toward the serosa (extraluminal or exophytic type) or lumen (endoluminal type). Clinical symptoms typically vary depending on the tumor size, growth type, and location. Most patients presenting with symptoms have tumors that exceed 5 cm in maximum dimension, and some tumors are as large as 30–40 cm at presentation. The most frequent symptoms include early satiety, gastrointestinal or intraperitoneal hemorrhage, and abdominal mass or pain. Intestinal obstruction and intestinal perforation can also occur. Associated symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss. Other patients with GISTs are asymptomatic and are incidentally diagnosed by abdominal imaging or endoscopy. No laboratory test can confirm or exclude the diagnosis of a GIST [7].

Radiologic exams are often essential in determining the size, location, extent of local invasion, and operative strategy for the treatment of GISTs. Imaging is also critical in restaging, monitoring the response to therapy, and performing follow-up surveillance for recurrence. Contrast-enhanced computed topography (CT) is preferred for initial screening and staging because of its superior ability to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the abdomen (Fig. 28.3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be preferred for the evaluation of GISTs in certain anatomic sites such as the rectum or liver. Tumors that are greater than 5 cm, lobulated, enhance heterogeneously, and have mesenteric fat infiltration, ulceration, or an exophytic growth pattern are more likely to demonstrate metastatic or recurrent behavior. Conversely, smaller GISTs, those with an endoluminal growth pattern, and those with a homogeneous pattern of enhancement tend to demonstrate less aggressive behavior.

While positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of GISTs is rarely required for the evaluation of localized disease, PET is capable of detecting sub-centimeter lesions and may therefore be useful for detecting an unknown primary site or monitoring the response to systemic therapy. PET can also help differentiate active tumor from necrotic or inactive scar tissue, malignant from benign tissue, and recurrence from nondescript postsurgical changes.

On upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, a smooth, mucosa-lined protrusion of the bowel wall may be present, with or without signs of ulceration (Fig. 28.1). Standard endoscopic biopsies usually do not obtain sufficient tissue for a definite diagnosis. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or forceps biopsies have a higher yield and may also be useful for excluding the diagnosis of other submucosal lesions (Fig. 28.2). Definitive tissue diagnosis is not required for a resectable lesion in which there is a high suspicion for a GIST, but biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis when metastatic disease is present or suspected. A biopsy is also required for patients with a locally advanced GIST who are being considered for neoadjuvant therapy. EUS-FNA of the primary site is preferred over percutaneous biopsy due to the risk of tumor hemorrhage and dissemination.

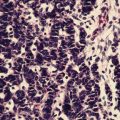

The gross pattern of GISTs is diverse but most are well-circumscribed nodular masses. However, they can also be multinodular and exhibit foci of cystic degeneration, hemorrhage, and necrosis. Microscopically, most GISTs can be divided into histologic subgroups including both spindle cell type, epithelioid type, and mixed variants. Intestinal variants are histologically more homogenous group of tumors. Differentiation between GISTs and other spindle cell tumors is typically based upon morphology, immunohistochemistry staining, and molecular analysis. Approximately 85–90 % of GISTs has gain-of-function mutations of KIT and PDGFRA genes and characteristically stain positive for either KIT (CD117), CD34, or DOG1. The level of expression can vary from diffuse and strong to focal and weakly positive. CD34, however, is not a sensitive or specific marker, staining only 50–80 % of gastric and small intestinal GIST. The morphologic identification of KIT negative remains a diagnostic challenge, but a newly discovered antigen known as DOG1 (discovered on GIST-1) can help to identify certain KIT-negative GISTs. DOG1 is a calcium-dependent, receptor-activated chloride channel protein, and it is expressed in GISTs independent of mutation type. In view of the cross-reactivity and expression of these antibodies in a variety of other spindle cell mesenchymal tumors considered in the differential diagnosis of GIST, a panel of antibodies is recommended and include CD117, DOG1, CD34, S10, desmin, smooth muscle actin, and keratin as indicated.

Several factors have been identified as contributing to clinical outcomes in patients with GISTs. The most reliable prognostic factors for GISTs are tumor size, location of the primary tumor, and the mitotic index [8]. Gastric tumors have a more favorable prognosis than the intestinal ones with similar characteristics [9]. Risk of metastatic disease or recurrence is higher for tumors greater than 5 cm and those demonstrating high cellularity, prominent nuclear pleomorphism, necrosis, greater than 5 mitoses per 50 high-power field (HPF), and invasion into adjacent structures. Historically, some GISTs were classified as “benign” based on a size less than 2 cm and favorable histologic features, but with long-term follow-up, it is becoming increasingly clear that virtually all GISTs have the potential for malignant behavior and recurrence.

The American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) and International Union Against Cancer (UICC) first included a TNM (tumor/node/metastasis) classification and staging system for GISTs in the 2010 7th edition of the cancer staging manual (Table 28.1) [10]. The T-categories are based on tumor size and then combined with mitotic rate and tumor site to define a clinical stage. Given the rarity of nodal metastasis with GISTs, any patient without examined regional nodes is considered to be N0. The presence of either nodal or distant disease is classified as stage IV. There remains some controversy as to whether or not the TNM system applies well to GISTs since factors known to predict outcomes such as mutation type and tumor rupture are not included.

Table 28.1

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (7th edition)

Primary tumor (T) | |

|---|---|

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

T1 | Tumor ≤2 cm |

T2 | Tumor >2 cm but <5 cm |

T3 | Tumor >5 cm but <10 cm |

T4 | Tumor >10 cm in greatest diameter |

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

|---|---|

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis* |

N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

*Note: If regional node status is unknown, use N0, not NX | |

Distant metastasis (M) | |

|---|---|

M0 | No distant metastasis |

M1 | Distant metastasis |

Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Group | T | N | M | Mitotic rate |

Gastric GIST* | ||||

Stage IA | T1 or T2 | N0 | M0 | Low |

Stage IB | T3 | N0 | M0 | Low |

Stage II | T1, T2 | N0 | M0 | High |

T4 | N0 | M0 | Low | |

Stage IIIA | T3 | N0 | M0 | High |

Stage IIIB | T4 | N0 | M0 | High |

Stage IV | Any T | N1 | M0 | Any rate |

Any T | Any N | M1 | Any rate | |

Small intestinal GIST** | ||||

Stage I | T1 or T2 | N0 | M0 | Low |

Stage II | T3 | N0 | M0 | Low |

Stage IIIA | T1 | N0 | M0 | High |

T4 | N0 | M0 | Low | |

Stage IIIB | T2–T4 | N0 | M0 | High |

Stage IV | Any T | N1 | M0 | Any rate |

Any T | Any N | M1 | Any rate | |

*Note: Also to be used for omentum | ||||

**Note: Also to be used for esophagus, colorectal, mesentery, and peritoneum | ||||

Any patient with N or M disease is classified as stage IV, irrespective of T stage | ||||

Histopathologic grade |

|---|

Low mitotic rate: ≤5 per 50 HPF |

High mitotic rate: >5 per 50 HPF |

Operative Therapy for Localized GISTs

Operative resection remains the treatment of choice for a localized GIST (Table 28.2). Complete surgical resection of the gross tumor and pseudocapsule including en bloc resection of any involved adjacent organs is recommended if possible. GISTs are fragile and should be handled with care to avoid tumor rupture. Both nonradical resection with a positive margin (R1) and tumor rupture are associated with adverse outcomes. Because lymph node involvement is exceedingly rare, extensive lymphadenectomy does not provide a survival advantage and is not recommended. Repeat resection is generally not indicated for microscopically positive margins on final pathology, although every effort should be made to obtain negative microscopic margins at the initial operation.

Table 28.2

Treatment summary for localized, recurrent, and metastatic GIST

Clinical scenario | Management |

|---|---|

Local disease | Complete en bloc resection with tumor-free margins |

Consider neoadjuvant therapy for patients with marginally resectable disease or those who would require total gastrectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, or an abdominoperineal resection or if the tumor is particularly large | |

Consider adjuvant therapy with imatinib for higher-risk tumors (>5 cm, >5 mitoses/50 HPF) | |

No role for conventional radiation or chemotherapy | |

Recurrent or metastatic disease | Treat with imatinib until treatment failure |

Consider dose escalation or other tyrosine kinase inhibitors for imatinib-refractory or resistance GISTs | |

Surgical resection of residual tumors of responding patients or symptomatic tumors may be considered |

Most gastric GISTs can be resected using a wedge resection with a 1–2 cm margin. For tumors along the greater curvature of the stomach, the omentum is removed from the stomach near the tumor. For lesser curvature lesions, a pyloromyotomy should be performed if the vagal nerves supplying the pylorus are disrupted. Many GISTs may be resected using a laparoscopic approach. Extraluminal tumors (serosal based) are easily localized laparoscopically, while endoluminal tumors may require concurrent upper endoscopy. In laparoscopic resections, the specimen should be removed from the abdomen in an endoscopic retrieval bag to avoid spillage or seeding of port sites. Sphincter-sparing surgery should be considered for rectal GISTs. In selected cases, neoadjuvant imatinib therapy may enable sphincter-sparing surgery and improve outcomes in patients with low rectal GISTs. Even when complete resection is achieved, many tumors can recur, often involving the liver and peritoneum.

Systemic Therapy

Systemic chemotherapy and radiation have minimal activity against GISTs and are not routinely recommended. Since tyrosine kinase activation occurs in the majority of cases, tyrosine kinase inhibition (TKI) has emerged as the primary therapeutic modality for metastatic or recurrent GISTs (Table 28.3).

Table 28.3

Summary of selected clinical trials on GISTs

Study [Ref] | Findings |

|---|---|

US-CDN (phase 3) [14] | No difference in PFS or OS between 400 mg qd and 800 mg qd dosing schedule |

EU-AUS (phase 3) [15] | Initial report: PFS advantage with 800 mg qd over 400 mg qd |

Follow-up report: No advantage with 800 mg qd dose | |

MetaGIST [18] | Combined data from UC-CDN and EU-AUS |

No OS with 800 mg qd schedule | |

Improved PFS for patients with KIT exon 9 mutation | |

ACOSOG Z9001 (phase 3) [25] | Adjuvant imatinib prolonged RFS but not OS |

3-year adjuvant imatinib prolonged both RFS and OS over 1 year | |

RTOG 0132/ACRIN 6665 (phase 2) [30] | Demonstrates role of neoadjuvant imatinib |

Demetri [31] | Sunitinib improved PFS and OS for patients with advanced GIST who were resistant to or intolerant of imatinib

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|