German pathologist Siegfried Oberndorfer recognized carcinoid tumors as a unique entity in 1907. Prior to his published case reports, these tumors were thought to be benign carcinomas, but Oberndorfer presented six patients with multifocal, pea-sized tumors of the ileum that appeared malignant on histologic examination.1 He named the disease “karzinoide” (carcinoma-like) to more accurately classify their clinical behavior. Today, the term “carcinoid tumor” provokes controversy among those who prefer more specific oncologic terminology for the disease, but it persists as an etymologic honorarium to the man who pioneered the field.2

The epidemiology of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (GI NETs) has evolved since data was first catalogued in the Surveillance Epidemiology End Results (SEER) database in 1973. At that time, the prevalence of GI NETs was 1.09 per 100,000 people per year. Forty years later, the prevalence is estimated at 3 per 100,000 people per year and GI NETs represent 0.5% of all newly diagnosed cancers. The cause of this increase is unknown. Common behavioral risk factors such as smoking and excessive alcohol use do not appear to play a role.3 The increased prevalence is therefore attributed to improved diagnostic capabilities and increased awareness of the disease.4

The term “GI NET” refers to a neuroendocrine tumor originating anywhere in the digestive tract from the stomach to the rectum (excluding the pancreas). Foregut tumors are those that develop between the mouth and the second portion of the duodenum, midgut from D3 to approximately the last third of the transverse colon, and hindgut from this part of the colon to the anus. In the United States, GI NETs are most commonly found in the small bowel (36%), followed by the rectum (34%), colon (15%), stomach (10%), and appendix (5%). These tumors are more common in whites (72.6%), followed by blacks (17.2%), and Asians (7.8%). The median age of onset is 60 and men and women are affected at near-equal rates.4,5 These trends hold true in Europe,6 but in Asia, rectal carcinoids are far more common (88.1% of GI NETs, 61.8% of all NETs).7 In general, gastric, rectal, and appendiceal tumors tend to be diagnosed while still localized. Small bowel and colonic NETs are less predictable, as approximately 30% have distant metastases at diagnosis, 30% have locoregional spread, and 30% have localized disease.5

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors arise from endocrine cells that derive from endoderm. These cells comprise only 1% of cells in the intestinal lumen, but are in aggregate the largest group of hormone-producing cells in the body.8–10 There are 17 known neuroendocrine cell types.9 The secretory function of these cells is mediated by G-protein-coupled receptors, ion-gated receptors, and receptors with tyrosine kinase activity. The bioactive peptides and hormones produced by these cells are the cause of the symptoms of carcinoid syndrome, and are also used to diagnose and monitor the disease.

There is a paucity of genetic studies on this group of tumors, given their relative rarity, but some important oncogenic molecular alterations have been described. In gastric and duodenal NETs, the best-described genetic alteration is loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the MEN1 locus on chromosome 11q13. The MEN1 gene is associated with the development of multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN1), which is caused by either an inherited or sporadic mutation.11,12 Few midgut or hindgut NETs are associated with mutations in MEN1. Recent studies suggest that alterations in CDKN1B, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, may lead to tumorigenesis in small bowel NETs.13–15 Additionally, total loss of chromosome 18 or loss of 18q markers are common in well-differentiated midgut NETs and are important in their initiation.11,16 Colorectal NETs are also associated with LOH at chromosome 18. In all locations throughout the GI tract, and similar to adenocarcinoma, major chromosomal instability and alterations of important tumor suppressor genes like p53 are most commonly seen in poorly differentiated GI NETs.11

The nomenclature of neuroendocrine tumors is a subject of much debate. In 2010, the World Health Organization suggested that low and intermediate grade neuroendocrine tumors be referred to as “neuroendocrine neoplasms” to better communicate their ability to metastasize, rather than use the generic term “tumor.” High grade tumors were designated “neuroendocrine carcinomas,” to better convey their adenocarcinoma-like behavior.17 This more precise nomenclature has not been widely accepted and thus the term “neuroendocrine tumor” persists.18

The malignant behavior of a GI NET can be inferred from its assigned level of differentiation and grade. Differentiation describes the extent to which tumor cells resemble their non-neoplastic counterparts, whereas grade attempts to describe the inherent aggressiveness of the tumor. Well differentiated NETs have characteristic arrangements of cells that resemble their tissue of origin. These cells are uniform in size and shape and often demonstrate strong immunohistochemical (IHC) staining by chromogranin A (CgA) or synaptophysin. Approximately 98% of GI NETs are well or moderately differentiated.19 Poorly differentiated NETs have disorganized architecture, irregular nuclei, and few neurosecretory granules (and thus stain poorly by IHC).18

Gastrointestinal NETs are divided into three grades (G1 to G3) depending on their proliferative rate. Most GI NETs are categorized as either G1 or G2, which correspond to the well and moderately differentiated categories.20,21 The universal reporting standard, the mitotic index, is determined by counting the mitotic figures on 40 to 50 high power fields of an H&E slide.18,20 A newer method, the Ki-67 index, labels neoplastic cells with an antibody to the Ki-67 antigen, and then reports the percentage of cells that stain positively.22 Table 45-1 shows how each system stratifies NETs into their respective grades. Grade can be communicated in a pathology report by either index. The divisions in each system correlate with disease prognosis.18,20–22

Neuroendocrine tumors are staged with the 2010 American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumor Node Metastasis system (TNM).23 The T stage is assigned based on the size of the tumor and depth of invasion. The N and M stages indicate whether nodal spread or distant metastases are present, respectively.24 Each portion of the GI tract has its own TNM staging system (Table 45-2), but all are similar in that stages I to IIIa indicate localized disease, stage IIIb locoregional disease, and stage IV metastatic disease. Each of these categories correlates with prognosis, which is heavily influenced by the resectability of the tumor (Table 45-3).25 Resectable stage IIIb disease is associated with a 95% 5-year overall survival (OS), but stage IIIb disease that is unresectable correlates with a 78% 5-year OS.26

TNM Staging System for Gastrointestinal NETs

| Gastric | All Small Bowel | Appendiceal | Colon and Rectum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TX | Primary cannot be assessed | |||

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |||

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ or dysplasia (size <0.5 mm). Confined to mucosa. | |||

| T1 | Tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa. Size ≤1 cm. | Tumor invades mucosa or submucosa. Size ≤1 cm. | Size ≤2 cm | Tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa. Size ≤2 cm. |

| T1a | Size ≤1 cm | Size <1 cm | ||

| T1b | Size >1 cm, but not >2 cm | Size 1–2 cm | ||

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria. Size >1 cm. | Tumor invades muscularis propria. Size >1 cm. | Size >2 cm but ≤4 cm, or with extension into cecum | Tumor invades muscularis propria or size >2 cm with invasion into lamina propria or submucosa |

| T3 | Tumor invades subserosa | Tumor invades subserosa without penetrating serosa (jejunal/ileal tumors), or invades pancreas or retroperitoneum (duodenal tumors), or invades into non-peritonealized tissues (any small bowel) | Size >4 cm or with extension into ileum | Tumor invades into subserosa or pericolic/perirectal fat |

| T4 | Tumor invades peritoneum or other organs | |||

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |||

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |||

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis | |||

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed | |||

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |||

| M1 | Distant metastasis | |||

Prognostic Stage Corresponding to TNM Designationa

| Stage | T | N | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| IIa | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| IIb | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIa | T4 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIb | Any T | N1 | M0 |

| IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

The prognosis of GI NETs is generally better stage-for-stage compared to similar site adenocarcinomas. Poor prognostic indicators for GI NETs are advanced age,27 carcinoid heart disease,28,29 elevated 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA),27,30,31 elevated chromogranin A (CgA),27,32 plasma neurokinin A (NKA) levels greater than 50 pg/mL,33 incomplete surgical resection,30,34 tumor spread,25,26 and high grade or poorly differentiated histology.35 The median survival of patients with localized, well-differentiated GI NETs varies widely. For appendiceal and rectal NETs, median survival is greater than 20 years, whereas for foregut, small bowel, and cecal NETs, median survival is approximately 10 years. Patients with nodal metastases have worse median survival (range 3 to 8.9 years), with the exception of appendiceal NETs, which maintain a median survival of more than 20 years. The median survival of those with metastatic, well differentiated GI NETs ranges from 4.8 years (duodenum, small bowel) to 5 months (colon). Patients with any type of localized poorly differentiated NET at diagnosis have a median survival of 2.8 years, a survival of 1.2 years with nodal involvement, and 5-month survival with distant spread.36

Three of the GI NET biomarkers have been shown to correlate with prognosis. Initial serum CgA levels greater than 200 U/L portend poor prognosis, and these patients have a median survival of 2.1 years, versus 7 years for those with levels less than 200 U/L.37 Elevated pancreastatin levels are also independent predictors of poor prognosis. In patients treated with somatostatin analogues, pretreatment pancreastatin levels greater than 500 pmol/L suggest poor survival.38 In surgically treated patients, elevated preoperative and/or postoperative pancreastatin levels, and the failure of the pancreastatin level to normalize after surgery, correlate with poor progression free survival (PFS) and OS.39 Patients with NKA levels greater than 50 pg/mL (drawn at any time) have a 2-year survival of 49%, whereas those with levels less than 50 pg/mL have a 2-year survival of 93%.33

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors are on average diagnosed 9.2 years after manifestation of the first symptoms.40 This is likely due to the rarity of these tumors, their indolent nature, and nonspecific presenting symptoms like abdominal pain and diarrhea.41 Correct and early diagnosis requires a thorough history and physical laboratory studies, imaging, and tissue confirmation.

There are three subtypes of gastric NETs. Types I and II are associated with hypergastrinemia, whereas type III are sporadic.42 Type I is the most common and is found in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis/pernicious anemia. They are generally benign (95%), multicentric (>60%), small (5 mm), and located in the gastric body or fundus. Type II gastric NETs are associated with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (ZES) in the context of MEN1 more than 70% of the time. The remaining 30% of these tumors are associated with sporadic ZES. These NETs have a 10% to 30% rate of metastasis,43 making them more aggressive than type I gastric NETs, though most metastases are confined to regional lymph nodes.44 Type II tumors occur in the gastric body, fundus, or antrum.43 Type III gastric NETs are rare and sporadic, but also the most aggressive type as 50% to 100% will metastasize, regardless of size. Type III gastric NETs usually occur in the antrum.43,45

Sporadic duodenal NETs occur as small (<2 cm) single lesions in the first and second parts of the duodenum. Forty to sixty percent of these tumors are associated with regional lymph node metastases, but fewer than 10% will metastasize to the liver, affording this tumor a good prognosis. The most common duodenal NETs are gastrinomas, somatostatinomas, and nonfunctional NETs.46 Gastrinomas are the most likely to cause hormonal symptoms and can do so sporadically or in the context of ZES and MEN1. Symptoms associated with elevated gastrin are secondary to the subsequent increase in hydrochloric acid, which causes reflux, peptic ulcers, GI bleeding and, rarely, perforation. The other types of duodenal NETs infrequently cause hormonal symptoms.43

Gastric and duodenal carcinoids are likely to be found incidentally during endoscopy. A large tumor burden may cause symptoms of abdominal pain, GI bleeding, or weight loss.47 Though gastric and duodenal NETs tend not to produce as much serotonin as their midgut counterparts, flushing can be seen in these patients. Patients flush intensely purple and with prolonged and repeated episodes, and a “leonine” appearance can develop.40

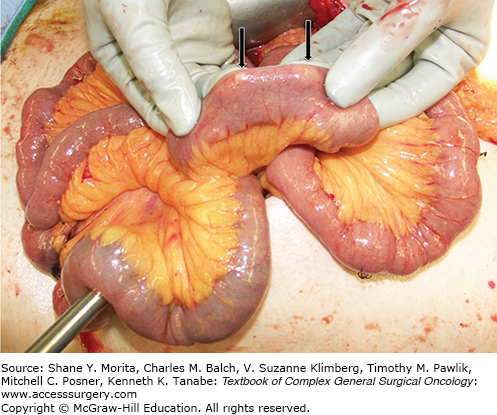

Small bowel NETs are small, can be multifocal, and often located within 60 cm of the ileocecal valve (Fig. 45-1). The disease has usually spread at the time of diagnosis—41% will have nodal involvement, and 30% will have distant metastases5,19,36 Symptoms are caused either by hormonal secretion or by the tumor itself (GI bleeding, bowel obstruction).

Carcinoid syndrome is caused by the production and release of substances such as serotonin, histamine, dopamine, and tachykinins by hepatic metastases. These products are released into the systemic circulation, thereby avoiding first pass metabolism.19,40,48 This syndrome is most commonly associated with small bowel NETs because of their propensity to metastasize to the liver, but actually manifests in only 10% to 20% of patients. The classic triad of symptoms is flushing, diarrhea, and bronchospasm, but arthropathy, scleroderma, cardiomyopathy, and symptoms of right-sided heart failure such as edema are also reported.48,49

The flushing of carcinoid syndrome is red-pink, involves the face and upper torso, and frequently transitions from the occasional, provoked episode to a frequent problem that causes permanent skin discoloration. Exercise, alcohol, and tyramine-containing foods (red wine, sausage, blue cheese, chocolate) are common provoking factors. Carcinoid syndrome produces secretory diarrhea by overwhelming the absorptive capacity of the colonic mucosa with fluid and ions secreted by the small bowel.40 These patients frequently have abnormal small bowel and colonic motility as well.50 Bronchospasm causes wheezing and these patients often demonstrate prolonged 1-second forced expiratory volume on pulmonary function tests.40

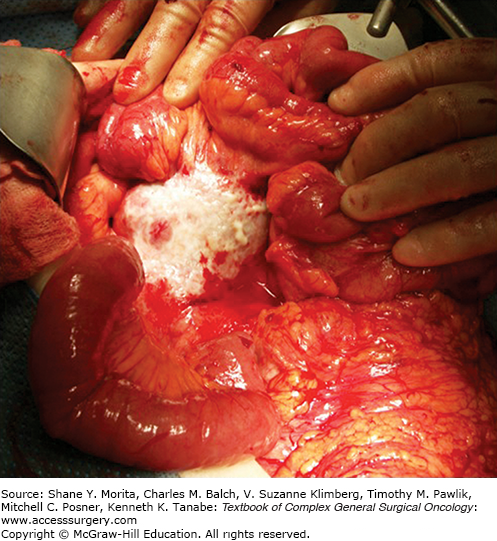

Midgut NETs tend to be small in size and are unlikely to cause symptoms of intraabdominal mass effect. Rather, the crampy, paroxysmal abdominal pain experienced by many patients is due to a desmoplastic reaction that causes mesenteric fibrosis (Fig. 45-2). The thickened mesentery may cause buckling of the jejunum or ileum, resulting in small bowel obstruction or disruption of the natural path of the bowel vasculature, ultimately leading to bowel ischemia.16,19

FIGURE 45-2

Intraoperative photo of a large mesenteric mass. The mesenteric lymph nodes become matted as a result of the desmoplastic reaction commonly seen with small bowel neuroendocrine tumors. Not all mesenteric nodal masses will be covered with a layer of fibrotic tissue, as seen in this photo.

Carcinoid heart disease will develop in 40% to 70% of patients with overt carcinoid syndrome, though only 10% to 20% of patients with carcinoid syndrome present with it.19,51–53 Patients may complain of exercise intolerance or fatigue, but may also be asymptomatic. The disease is caused by sustained release of serotonin, tachykinins, histamine, and prostaglandins from hepatic metastases into the systemic circulation, which exposes the right-sided chambers to high concentrations of these substances, resulting in valvular thickening and formation of fibrous plaques on the tricuspid and pulmonic valves.54 Tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonic stenosis are the most common problems, and may be detected on physical exam or by transthoracic echocardiogram prior to the patient becoming symptomatic. Right ventricular dysfunction or failure is a late manifestation of the disease. Progression of cardiac dysfunction correlates with high hepatic tumor burden and extremely high levels of urinary 5-HIAA, rather than absolute duration of the symptoms of carcinoid syndrome.51

Appendiceal carcinoids are often an incidental finding, either during appendectomy or surgery for an unrelated indication.55 Approximately 54% of patients will present with symptoms of acute appendicitis, though these symptoms are unlikely caused by the tumor as only one-third arise at the base of the appendix.16,56 Most appendiceal NETs are small (<1 cm), and metastatic spread is rare. Distant metastases are most likely in patients with tumors greater than 3 cm, but even then in only 44% of cases.55

Colonic NETs are problematic as they are concomitantly asymptomatic but aggressive. Nearly 66% have metastasized at the time of diagnosis. The large luminal diameter of the colon prevents development of symptoms of mass effect, and their rare hormone production means that fewer than 5% of patients develop carcinoid syndrome.57 These tumors are usually found in the right colon.

Rectal NETs are usually discovered during a routine exam or during evaluation for symptoms of pain, bleeding, or constipation thought to be caused by a benign condition.16,58 These tumors are usually found 4 to 8 cm from the anorectal junction.59 Fortunately, rectal NETs are less aggressive than their colonic counterparts. Approximately 82% of patients have localized disease at the time of diagnosis.57 Carcinoid syndrome is rarely associated with these tumors.

Historically, the diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor relied on an elevated urinary level of 5-HIAA. This marker is elevated in approximately 88% of all carcinoids, with the highest levels seen in bronchial and midgut NETs.60 Its specificity as a tumor marker is limited, however, as levels are altered by consuming serotonin-containing foods.61 This test has mostly been supplanted by drawing the serum markers serotonin, CgA, and pancreastatin. Other markers, such as plasma 5-HIAA, serum NKA, or serum neuron-specific enolase have shown some utility in the diagnosis and follow-up of GI NET, but are not as widely used.

Serum serotonin is often the first biomarker drawn when carcinoid syndrome is suspected. Elevated levels are found in 96% of midgut and 43% of foregut NETs, but its moderate sensitivity and specificity limit its use diagnostically. Serotonin indicates tumor functionality, but does not correlate with tumor burden.62 Further, caution must be used when interpreting results from different centers, as a variety of serotonin assays are available.

5-HIAA is the primary metabolite of serotonin and also indicates tumor functionality, rather than tumor burden. Its specificity for NETs is excellent (100%), but its sensitivity is only 35.1%.63 This marker can be obtained from a 24-hour urine collection, or from a fasting plasma level, which is more sensitive and more convenient for the patient (but expensive).64–66

Chromogranin A is a protein found in the secretory granules of both normal and neoplastic neuroendocrine cells throughout the body. Elevated serum levels are found in the majority of patients with GI NETs,67 though elevated levels can also be found in postmenopausal women, patients with impaired renal function, hepatic failure, chronic atrophic gastritis, or those taking proton pump inhibitors.68–70 Somatostatin analogue therapy also causes elevation of CgA. The sensitivity and specificity of this marker depends on the assay used to measure it, but ranges from 67% to 93% and 85% to 96%, respectively.71 The highest CgA levels are seen in midgut NETs68 and studies have demonstrated a direct correlation between serum levels and metastatic hepatic tumor burden.37 CgA levels do not correlate with symptom severity.72

Pancreastatin is a post-translational fragment of CgA and is elevated in approximately 80% of GI NET patients.73 It is used for diagnosis, prognosis, as an estimate of hepatic tumor burden, and as a marker of disease progression.74,75 Pancreastatin assays do not cross react with CgA, and levels are not affected by the use of proton-pump inhibitors, nor by treatment with somatostatin analogues.70 This marker demonstrates consistently better sensitivity and specificity for GI NETs than CgA, and is often the only pathologically elevated marker in NET patients.73,76

Neurokinin A is not a diagnostic marker and the current level, rather than the trend, is used to estimate prognosis. However, comparison of a current NKA level to a pretreatment level may be helpful assessing treatment efficacy.33

Imaging is used in the diagnostic workup of GI NETs for primary tumor detection, staging and identification of metastases, surgical planning, and evaluation of somatostatin receptor expression. The most common diagnostic modalities are computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), endoscopy, ultrasound (US), somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS), and positron emission tomography (PET).77–79 Effective workup usually requires use of multiple modalities.

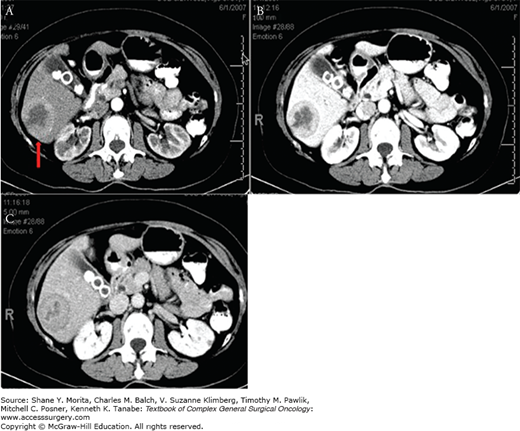

Computed tomography (CT) scans are most useful for disease staging and surgical planning. These scans have an average sensitivity of 73% for detecting the primary tumor site,78 though a wide range has been reported (43% to 90%).80,81 CT scans are better at detecting metastatic tumors, as they have an 80% sensitivity for hepatic metastases,78,80 and a 75% sensitivity for extrahepatic metastases.78 Hepatic metastases are optimally detected with a triple phase CT scan obtained with intravenous (IV) contrast (Fig. 45-3). Hypervascular tumors are best identified in the late arterial phase, whereas hypovascular tumors are best seen in the portal venous phase when the normal liver parenchyma enhances.77,79

Computed tomography enterography is useful for detection of primary GI NETs. A baseline CT scan is obtained followed by oral ingestion of approximately one and a half liters of a neutral liquid (like water) to distend the bowel. CT scans are then obtained with and without IV contrast.79 One series reported a sensitivity of 92.7% for this modality, and that it significantly outperformed capsule endoscopy for primary tumor detection.82

Magnetic resonance imaging is used for enhanced delineation of local tumor invasion, detection of metastases, and disease staging in patients with renal failure or intolerance to iodinated contrast agents. It is not routinely used for primary tumor detection.77–79,83 The sensitivity of a contrast-enhanced MRI is superior to that of a triple-phase CT in detecting liver metastases (95.2% vs. 78.5%, respectively),84 but its use is limited by its availability, expense, and the length of time required to complete the exam.

Endoscopy, be it esophagogastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy, can be used to detect primary GI NETs and provide tissue for diagnosis. It can also be combined with ultrasound (endoscopic ultrasound, EUS) for local staging. In the case of small, isolated tumors endoscopy can provide the means to excise the tumor for cure.79,85 Despite its many advantages, it is rarely used as an isolated diagnostic modality. A suspected duodenal NET is localized by EUS only 45% to 60% of the time.86 Double balloon enteroscopy can be employed to search for unknown primary small bowel NETs, but only confers a 33% detection rate.87 Video capsule endoscopy has also been employed to search for unknown primary NETs, but has a diagnostic yield of only 45%.88

Conventional US plays virtually no role in the detection of primary GI NETs, but can be used to assess metastatic hepatic tumor burden. The sensitivity of standard B-mode US to detect hepatic metastases is inferior to CT and MRI, given its lack of contrast. However, the addition of microbubble contrast agents greatly increases this method’s detection rate, making it a viable alternative for assessment of hepatic tumor burden in patients unable to tolerate any contrast agents.89

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy is used both as a diagnostic modality, and to assess whether patients will benefit from peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT).90 Somatostatin is an endogenous peptide that inhibits the proliferative and secretory functions of a variety of target cells throughout the body.91 Naturally occurring somatostatin has a half-life of only a few minutes, necessitating that man-made analogues be used for SRS. The five types of somatostatin receptors, SSTR1–SSTR5, are upregulated in more than 80% of well differentiated GI NETs.92,93 SSTR2 is the most frequently expressed receptor on NETs and is the basis for somatostatin analogue imaging and treatment.93,94

The gold standard of SRS is the OctreoScan, which utilizes 111In-DPTA-octreotide as its radiotracer.95 On its own, the study produces a planar image with dark spots indicating locations where the radiotracer has bound to SSTR2 (and to a lesser extent, SSTR5 and SSTR3).96 The whole body image is captured at 4, 24, and 48 hours after radiotracer administration to differentiate between pathologic and physiologic uptake, which is especially important when the suspected primary tumor is located in the small bowel (Fig. 45-4).77 It has moderate sensitivity (80%) and good specificity (>95%) for detecting primary GI NETs, but misses 17.5% of hepatic metastases that are otherwise detected on MRI or CT.84 From a surgical perspective, the OctreoScan is best used as an adjunct to CT and MRI in cases where the primary tumor remains undetected or when the extent of metastatic disease is unclear.97 In cases where CT or MRI fails to detect the location of the primary tumor, OctreoScan can locate the primary in an additional 39% of patients.98 Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) can be combined with the OctreoScan, providing a cross-sectional 3D image that improves the diagnostic accuracy of SRS.90 Greater improvement of the OctreoScan’s structural and functional imaging capabilities is achieved by combining SPECT with CT.90,99

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree