Fig. 9.1

Number of new gastrointestinal cancers in SSA and the world in 2012 and projected increase by 2030 (IARC 2016)

Sub-Saharan cancer statistic estimates are limited by the lack of accurate mortality statistics as cancer surveillance units and accurate epidemiological data are largely lacking. However, estimates can be made using the population based cancer-registries that have been developed in recent decades such as the (Ferlay et al. 2013) database of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (Ferlay et al. 2015; Parkin et al. 2014).

The most common cancers in Sub-Saharan Africa are cervical, breast and prostate cancers. These are followed by the GI tract cancers. Liver cancer is the 4th most common cancer followed closely by colorectal and oesophageal cancer. Gastric cancer is the 9th most common cancer. The incidence rates of gastrointestinal cancers are increasing and this chapter will give a brief overview of following conditions:

Oesophageal

Liver

Gastric and

Colorectal cancers

9.2 Oesophageal Cancer

9.2.1 Epidemiology

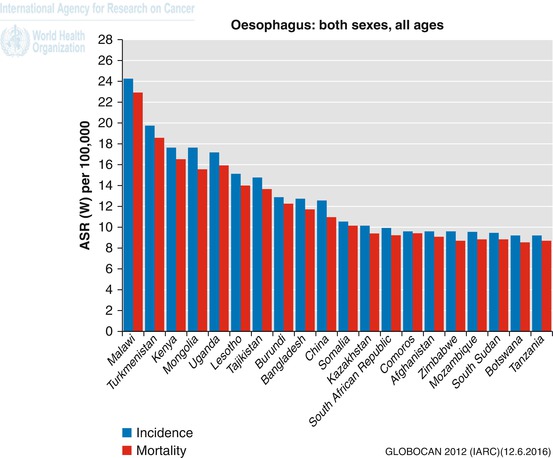

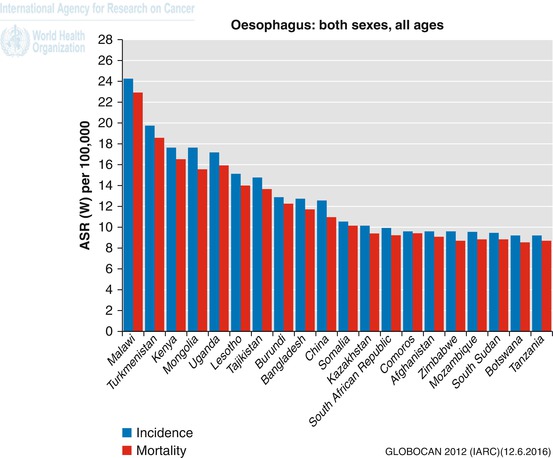

This accounts for nearly 4% of all cancer cases in SSA and is the 8th most common cancer with 24,400 cases reported in 2012 (1.4:1 Male:Female ratio) (Parkin et al. 2014). The highest incidence is in East Africa and although the cause of this remains unproven, some association with micronutrient deficiencies has been reported (Schaafsma et al. 2015). In 2012, Malawi had the highest incidence of oesophageal cancer in the world and there were 11 SSA countries in total in the top 20 countries worldwide (IARC 2016; Fig. 9.2).

Fig. 9.2

Age standardised incidence and mortality rates for the top 20 countries worldwide (IARC 2016)

Between 1977 and 2014, 16,523 adults ages 16 and above had gastroscopy in a teaching hospital in Lusaka, Zambia (Kayamba et al. 2015). 437 (2.7%) patients were diagnosed with oesophageal cancer during this period. Twenty-five percent were under 45 years of age and 70% under 60 years. Over this period, the incidence of oesophageal cancer increased in each decade and most of these increases were in patients under 45 years (Kayamba et al. 2015).

The peak age range was 45–64 years, and the predominant histopathological type is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). In a series of 328 patients with confirmed oesophageal cancer reported from Tanzania, 96% were found to be squamous cell carcinomas (McHembe et al. 2013). The patients usually present late thus curative surgery is often not possible. The overall prognosis is poor and even palliative treatment is limited (Kachala 2010). Known risk factors for oesophageal SCC include smoking, excessive alcohol, poor diet, ingestion of extremely hot beverages, and consumption of foods contaminated with a fungus called Fusarium Verticulloides and Fusarium Moniliforme (Kachala 2010). Increase in recognition stems from improvements in diagnostic abilities of more SSA countries with respect to increase in tertiary centers where barium swallow, upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy, more trained specialists are available (Kachala 2010).

9.2.2 Diagnosis

Current gold standard diagnostic workup in high-income countries would begin with upper GI endoscopy and biopsy of a suspicious lesion. Thorough staging normally consists of CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis to look for distant metastases. Provided there is no evidence for distant metastases, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is then used for accurate locoregional staging. Integrated PET/CT imaging is employed to look for distant metastases in patients believed to be suitable for surgery or other forms of curative therapy. Imaging will be repeated after any neoadjuvant treatment with chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy.

Low and middle income countries in SSA are less likely to have good access to some or all of the above investigations. Diagnosis may be possible through contrast studies such as a barium swallow. Pathological diagnosis can suffer from long delays (Adesina et al. 2013). CT scanning may be available in big cities, but EUS and PET are not yet affordable options. Staging may therefore employ X-ray examination of the chest and ultrasound for the identification of chest and liver metastases.

9.2.3 Treatment

In high-income countries, a multimodal approach that includes surgery is the gold standard treatment for patients with locally advanced disease (Pennathur et al. 2013). However in SSA, surgery is rarely an option since the majority of patients present at a late stage of disease. In a series of 328 patients with confirmed oesophageal cancer reported from Tanzania, 81.7% presented late with advanced stage of cancer (McHembe et al. 2013). Over 90% of 1868 patients with oesophageal cancer in South Africa over a 30 year period presented with dysphagia to solids and only 103 (5.5%) were eligible for curative surgery (Dandara et al. 2016).

Oesophagectomy is uncommon because of late presentations. In the report by Dandera et al. (2016), 103 patients had surgery but operative outcomes were not presented. The median survival of those operated on was 19.9 months. The results of open Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy from one hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia showed a high perioperative mortality of 28% (Ahmed 2000). However, this is unsurprising given that the surgery was mainly employed with palliative intent and the setting lacked the resources of a high quality critical care unit.

Alternative palliative options are not well reported and in resource poor environments, palliative stenting with self-expanding metal stents can give patients symptomatic relief and improve their quality of life (Thumbs and Borgstein 2010). A large series of oesophageal stenting from South Africa, showed successful stenting without radiological guidance (Govender et al. 2015). In the series, there were only 6 (1.3%) complications of 480 inserted stents and no mortality. However the complications were iatrogenic tracheo-oesophageal fistula (2), false tracts (3) and one perforation (Govender et al. 2015).

In the large series from South Africa, the commonest palliative treatment offered was external beam radiation to 570 of 1685 (34%) patients (Dandara et al. 2016). This was followed by the insertion of Proctor Livingstone tube in 27% and radical chemoradiation in 14%. Median survival for patients with tube insertion was 85 days, it 96 days for patients who had chemotherapy alone, and median survival for those who had radiotherapy was 96 days (Dandara et al. 2016).

In the developed world, oesophagectomy is now centralised in large hospitals who offer a variety of factors to improve mortality, including enhanced recovery programmes, high volume surgeons, other specialists to manage complications, for example interventional radiologists and cardiologists etc. In SSA where surgery is used, the limited access to chemotherapy and radiotherapy makes it unlikely that neoadjuvant treatment is given prior to surgery. In 2012, only three centres in Malawi were able to offer oesophagectomy as a treatment and no radiotherapy or chemotherapy was available (Thumbs et al. 2012). However, these were available in South Africa (Dandera et al. 2016). Overall, while North America and Western Europe had 14.89 and 6.12 teletherapy machines per million people, the average is less than one machine per million people in the whole of Africa (Abdel-Wahab et al. 2013). Radiation therapy plays a pivotal role in the management of oesophageal cancer, particularly of the squamous cell histopathological subtype (van Hagen et al. 2012) and increasing radiotherapy service in SSA is essential to cope with the projected incidence of oesophageal cancer. The mortality-incidence ratio (MIR) for oesophageal carcinoma in SSA in 2012 was 0.93 compared to 0.87 in Europe, 0.88 in Asia and 0.95 in North America (IARC 2016). MIR is a proxy indicator for survival that allows for regional and racial comparisons (Hebert et al. 2009; Vostakolaei et al. 2010).

9.3 Liver Cancer: Hepatocellular Cancer, Metastatic Cancer

9.3.1 Epidemiology

Liver cancer accounts for over 6% of all cancer cases in SSA and is the 4th most common cancer with 39,000 cases (1.8:1 Male: Female ratio) (Parkin et al. 2014). The highest incidence is in Western African men. Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 90–95% of primary malignant tumours of the liver in SSA (Kew 2012). In a series of 713 patients from Nigeria, hepatocellular cancer (HCC) accounted for up to 75% of all malignant liver tumours while metastatic liver cancer made up approximately 17% (Abdulkareem et al. 2009). HCC is not uniformly distributed worldwide with a large proportion associated with poorer regions (Kew 2013). The true incidence in SSA is probably underestimated due to the lack of a definitive diagnosis in many patients and or record in cancer registries (Kew 2013). Chronic HBV is the major cause in SSA natives; additional causes include Aflatoxin B1 and iron overload (Kew 2013; Ladep et al. 2014). These risk factors and the prevalence of HIV have meant that West Africa has a particularly high prevalence of HCC (Tognarelli et al. 2015). In 2012, 11 West African countries were in the top 20 of African countries with the highest incidence of liver cancer (IARC 2016; Fig. 9.3).

Fig. 9.3

Age standardised rates of incidence and mortality of liver cancer in Africa in 2012

9.3.2 Diagnosis

Early HCC is asymptomatic, therefore late presentation is common. This includes a painful right upper abdominal mass, abdominal swelling, weight loss and easy satiety. A triad of abdominal pain, abdominal swelling and jaundice has also been described (Ladep et al. 2014). A history of recent significant weight loss and upper abdominal pain especially in native African males of 20–50 years should raise some suspicion. An abdominal USS should help confirm the presence of a liver tumour in the absence of specialized radiological equipment like CT or MRI scans. Elevated levels of AFP helps in conjunction with other findings. Percutaneous transabdominal core-needle liver biopsies under USS guidance will give histopathological diagnosis.

9.3.3 Treatment

In high income countries, the optimum curative option for HCC is surgical resection with partial hepatectomy. However, there must be adequate liver function in the remaining liver for this approach to be successful and if not then the only other curative option is liver transplantation. An array of other non-surgical treatment options are available for patients that are not suitable for transplantation:

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA)

Percutaneous Ethanol Injection (PEI)

Transarterial Chemoembolization (TACE)

Radiotherapy

Chemotherapy

In SSA late presentation makes curative treatment including surgery a rare exception. In a series reported form Nigeria, over 96% of patients were offered symptomatic treatment only (Ndububa et al. 2001). In a review of 465 patients with liver cancer in Ghana, only 8% of patients were judged curative using the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) algorithm (Gyedu et al. 2015). However, none of these patients had surgery, ablation or embolization.

The prognosis of liver cancers in SSA is extremely poor with patients rarely reaching surgery and over 90% dying within the first 12 months of symptom onset (Kew 2013). The main strategy for treatment has targeted prevention in the form of Hepatitis B vaccinations. Infant vaccination with HBV vaccine has been largely adopted by most national immunisation programs but coverage has been shown to be under 80% in many countries where HBV is most prevalent (Jemal et al. 2012). Surveillance of high-risk group of high risk groups could be considered.

9.4 Gastric Cancer

9.4.1 Epidemiology

Gastric cancer accounts for under 3% of all cancer cases and is the 9th most common cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa with 18,100 cases in 2012 (1.2:1 Male: Female ratio) (Parkin et al. 2014). Peak age incidence in native African patients is at 3rd to 4th decade with late presentations common (Asombang et al. 2014). Gastric cancer is associated with H pylori and Epstein Barr Virus. However while H pylori prevalence rates as high as 92% have been reported in SSA, the majority of these patients will not develop gastric cancer and gastric cancer risk is intermediate at 4.3 per 100,000 (Asombang and Kelly 2012).

There is a possible difference in patterns of genomic instability in gastric cancers between Europeans and Africans (Buffart et al. 2011). The study showed microsatellite instability (MSI) in 24% of Black South Africans and 22% of Caucasian South Africans compared to only 3% of British Caucasian gastric cancers. There were differences in copy number variations between the three groups as well suggesting a possible difference in molecular mechanisms (Buffart et al. 2011).

9.4.2 Diagnosis

The high prevalence of peptic ulcer disease can contribute to delays in diagnosis. In a series from Nigeria, the most common presenting symptom of gastric cancer was upper abdominal pain in 82.6%, but most of these patients had commenced empirical treatment for peptic ulcer disease without endoscopy or contrast studies to confirm the diagnosis (Osime et al. 2010). Patients may often present with signs and symptoms of advanced disease including gastric outlet obstruction, haematemesis and perforation. In a series of 232 patients from Tanzania, 92.1% presented with late advanced gastric cancer (Mabula et al. 2012). Diagnosis is usually confirmed with UGI endoscopy and biopsy. In the absence of flexible endoscopy services, barium meal may help with diagnosis by showing mucosal irregularities, shelving or shouldering lesions or rigidity on fluoroscopy in cases of linitis plastica.

9.4.3 Treatment

Multimodal therapy with perioperative chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy plus surgery is the gold standard in high-income countries. In SSA surgery, whether curative or for palliation, is the mainstay of treatment. Curative gastric resection is only usually attempted for early presenters. Palliative surgery is relatively common especially gastrojejunostomy for pyloric obstruction. In a series from Tanzania, 96.1% of patients underwent a surgical procedure with 53.8% receiving a gastro-jejunostomy and gastric resection in 23.4% (partial or total) (Mabula et al. 2012). Only five of the 53 gastric resections were deemed R0 or curative with macroscopic clearance of disease and histological margins free of tumour. Chemotherapy was used in 24.1% of patients and radiotherapy in 5.1%. In high-income countries there is an established role for endoscopic stents to palliate gastric outlet obstruction (Khashab et al. 2013). However, owing to a lack of facilities gastrojejunostomy is still likely to be the most common method used to treat this condition in SSA (Jaka et al. 2013).

9.5 Colorectal Cancer

9.5.1 Epidemiology

Colorectal cancer accounts for 4.5% of all cancer cases and is the 6th most common cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa with 28,200 cases (1:1 Male: Female ratio) (Parkin et al. 2014). There are differences in the epidemiology of colorectal cancer between sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and the western world that suggests possible alternate aetiological pathway (Saluja et al. 2014; Irabor and Adedeji 2009). In SSA, the age of onset is younger; tumours are more aggressive; colonic distribution is different (Taha et al. 2015; Rotimi and Abdulkareem 2014; Cronjé et al. 2009) with the most common site being the rectum (Irabor et al. 2010) and the association with polyps is unclear (Williams et al. 1975), (van’t Hof et al. 1995). Studies from SSA have shown a lower mutation of K-ras gene (21–32%) and BRAF (0–4%) in CRC compared to the developed world (Abdulkareem et al. 2012; Raskin et al. 2013). Recent studies have shown differential CpG methylations across 2194 genes between Nigerian and British patients with colorectal cancer of which, 1986 (90.5%) genes were more methylated in Nigerians (Abdukareem et al. 2016).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree