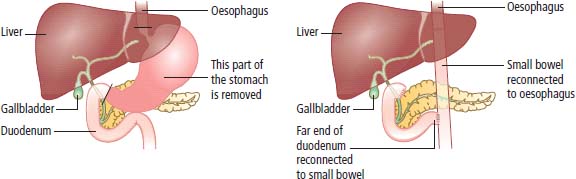

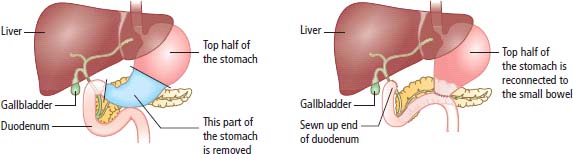

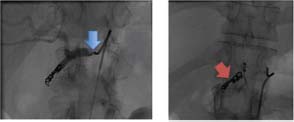

8 Gastric cancer is the 13th most common malignancy in the United Kingdom and constitutes approximately 2% of all cancers. The male-to-female ratio is 1.5:1. In 2010, nearly 7266 people were diagnosed with stomach cancer in the United Kingdom and 4830 died of stomach cancer. The average age at presentation is 65 years. The survival for gastric cancer has tripled over the last 25 years but currently only 18% of patients are alive 5 years after diagnosis (Table 8.1). Surprisingly, gastric cancer is the second most common cause of cancer deaths worldwide with 988,000 new diagnoses in 2008. There are extreme geographical variations, with the incidence being five times higher in Japan than in the United States. The incidence of gastric cancer has fallen in the industrialized world over the last few decades. This is particularly the case for distal tumours of the stomach. It had been thought that one of the reasons for the decrease in the West is better food refrigeration and decline in the use of salt as a food preservative. Whilst smoking increases the risk of stomach cancer, diet also has an important role. Higher consumption of citrus fruit, allium vegetables (the onion family) and bras-sicas (the cabbage family) all reduce the risk; so eat fresh fruit and vegetables. In contrast, a high salt intake (>6 g/day) and Asian pickled vegetables increase the risk of stomach cancer. In 1926, the Nobel Prize for medicine was awarded to a Dane, Dr Johannes Fibiger, who had described a nematode worm that he called Spiroptera carcinoma, which caused stomach cancers in rats that he caught in an infested sugar refinery. It was subsequently shown that the cancers were in fact only metaplasia and that the cause was vitamin A deficiency. Although Fibiger has been branded a fibber, it turns out that chronic infection is the cause of most human gastric cancers. The single most common cause of gastric cancer is infection with Helicobacter pylori: probably the most common chronic bacterial infection in man. This bacterium colonizes over half of the world’s population. Infection is usually acquired in childhood and, in the absence of antibiotic therapy, persists for the life of the host. How H. pylori causes gastric cancer remains unclear. Strains that have cytotoxin-associated gene (CagA) are more oncogenic and the products of these genes regulate protein secretion by epithelial cells. In addition, chronic H. pylori infection leads to the local production of inflammatory cytokines that are also thought to be involved in oncogenesis. Infection by H. pylori explains the aetiology of cancers developing in patients with atrophic gastritis. Helicobacter infection is more common in patients with gastric cancer than in “controls”, particularly in younger patients. Table 8.1 UK registrations for gastric cancer 2010 Patients with gastric cancer generally present to their general practitioner with symptoms of abdominal pain. Classically, the pain is epigastric and worse with meals. The differential diagnosis includes benign peptic ulceration. The routine prescription of protein pump inhibitors, without investigation by endoscopy, may lead to late diagnosis and the presence of advanced disease at diagnosis. Because the symptoms of gastric cancer are very similar to those of peptic ulceration and because peptic ulceration is very common and not necessarily routinely investigated, early diagnosis of gastric cancer in the West presents a difficult problem. Fewer than 2% of patients with first-time dyspepsia will have gastric cancer but the risk is greater in people over 55 years and those with dysphagia, vomiting, weight loss, anorexia or symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding. Walk-in endoscopy clinics, however, are becoming much more widely available in the United Kingdom, and it is hoped that they will impact upon survival figures for gastric cancer. After initial assessment, which should include a full blood count, liver function tests and chest X-ray, more specialized investigations should be undertaken. These should include endoscopy with biopsy, ultrasonography and CT imaging of the abdomen and chest. There have been advances in endoscopic ultrasound that have allowed improvements in local staging of gastric tumours. These improvements are such that mucosal invasion can be distinguished from submucosal invasion. The majority of patients with gastric cancer present with inoperable disease; only 20% of patients have disease that is potentially curable. The TNM staging system is widely used for staging gastric cancer, as with all TNM staging it may be modified by a prefix and a suffix (Table 8.2). Table 8.2 Prefixes used to qualify TNM staging Ninety-five per cent of all gastric tumours are adenocarcinomas. The remainder are squamous cell cancers and lymphomas. Small cell cancers are reported only rarely. In around 5% of the cases, the stomach wall is diffusely involved by cancer resulting in a rigid thick stomach wall called linitis plastica or leather bottle stomach. The only significant chance for a cure rests with surgery. Laparoscopic staging is carried out prior to definitive laparotomy. There is considerable debate concerning the operative procedures of first choice. Older retrospective data suggested that survival was improved with total gastrectomy compared with subtotal gastrectomy. Current practice is total gastrectomy for proximal tumours in the upper third of the stomach and subtotal gastrectomy with resection of adjacent lymph nodes for distal lower two-thirds cancers (Figures 8.1 and 8.2). The operative mortality in the United Kingdom varies from 5% to 14% and is directly related to the number of these operations performed by the surgeon. Figure 8.1 Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. (Roux-en-Y anastomosis is named after a Swiss surgeon, César Roux rather than the restaurateur brothers of the same surname.) Reproduced with permission of CancerHelp UK. Surgical developments have been led by the Japanese, who have to deal with the highest incidence of carcinoma of the stomach in the world. The current recommendation by the Japanese Society for Research in Gastric Cancer is for extensive lymphadenectomy, which involves the removal of the lymphatic chains along the coeliac axis and hepatic and splenic arteries. This sort of dissection also has the advantage of allowing more accurate staging for gastric cancer and has been associated with improved survival. Tumours of the gastro-oesophageal junction are increasing in the West and are treated surgically by subtotal resection of the oesophagus, along with the cardia and gastric fundus. A few patients are diagnosed with early-stage disease where the cancer is confined to the mucosa and submucosa, most commonly in patients who are on an endoscopic surveillance programme in East Asian countries with high incidences of gastric cancer. These early-stage-localized gastric cancers may be treated with curative endoscopic mucosal resection and survival is in excess of 90%. Advances in endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography and endoscopic surgery thus have produced great improvements in limiting the morbidity of interventional therapies. Significant improvements have been seen in Japan as a result of the wide-scale implementation of screening endoscopy. In Japan, up to 40% of patients are found to have early-stage tumours, which contrasts with the situation in the West. A large randomized trial showed that perioperative chemotherapy (before and after surgery) increased rates of surgery, progression-free survival and overall survival in gastric cancer. The most widely used chemotherapy regimens are epirubicin, cisplatin and infusional 5-fluorouracil (5FU) (ECF) or epirubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine (ECX). Figure 8.2 Partial gastrectomy. Reproduced with permission of CancerHelp UK. Patients with inoperable local disease or metastases may be treated with palliative chemotherapy. Over the years, many treatment programmes have been introduced and the majority have contained 5FU. There is uncertainty as to whether or not combination therapy offers benefit. The response rates are higher but the overall survival is similar for combination chemotherapy compared with single-agent 5FU treatment. In the 1970s, there was considerable enthusiasm following the introduction of a combination therapy containing 5FU, adriamycin (doxorubicin) and mitomycin C. This treatment schedule, known as the “FAM regimen”, was initially reported as leading to responses in 40% of patients, with a median duration of response of approximately 9 months. Randomized trials have since shown that the same order of response can be obtained with single-agent 5FU, with the same expectations of survival. In recent times, there has been considerable support for combination chemotherapy using epirubicin and cisplatin with either continuous infusion 5FU (ECF) or its oral prodrug capecitabine (ECX) or a combination of epirubicin, oxaliplatin and capecitabine (EOX). A surprising recent discovery is that about 20% of gastric cancers overexpress the epidermal growth factor receptor HER-2 and are thus potentially amenable to treatment with the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab or the small molecule lapatinib that targets this receptor in breast cancer too. Currently, NICE approves the use of trastuzumab for patients with metastatic gastric cancers that strongly overexpress HER-2. Occasionally, bleeding from inoperable tumours may be alleviated by embolization (Figure 8.3) or radiotherapy. Figure 8.3 Coil embolization, using a detachable platinum coil inserted by interventional radiologist. To reduce haemorrhage from a primary gastric tumour, selective catheterisation of the gastroduodenal artery In the West, more than two-thirds of patients present with advanced tumours. The median survival of patients with advanced local disease or metastatic tumour is approximately 6 months. Case Study: The belly of an emperor.

Gastric cancer

Epidemiology and pathogenesis

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registration

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5-year overall survival

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Gastric cancer

2

3

14th

10th

1 in 120

1 in 64

–28%

–32%

17%

18%

Presentation

Staging and pathology

Prefix

Means staging is based on:

c

Clinical examination

p

Pathological examination of a surgical specimen

y

Assessment after neoadjuvant therapy

r

Assessment of recurrence

a

Assessment at autopsy

Suffix

G (1–4)

Grade of tumour

R (0–2)

Completeness of resection margins (none, microscopic, macroscopic)

L (0–1)

Invasion into lymphatic vessels (none, present)

V (0–2)

Invasion into veins (none, microscopic, macroscopic)

Treatment

Surgery

Adjuvant treatment

Treatment of metastatic or locally inoperable gastric cancer

was followed by coil embolisation

was followed by coil embolisation  .

.

Survival

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree