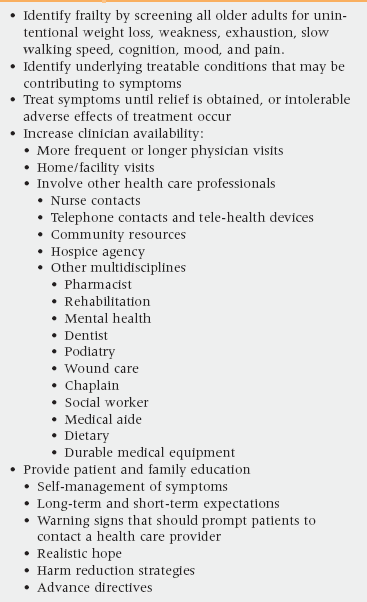

29 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the components of the two dominant theoretical concepts of geriatric frailty, and compare their approaches to defining or identifying frailty. • Discuss the strengths and limitations of each of these two theoretical concepts for clinicians in identifying frail aged patients in their practices. • Contrast the concepts of frailty and disability. • Discuss whether and how the concept of frailty has usefulness in geriatric clinical care beyond a focus on specific diseases and disabilities. • Describe examples of specific potentially treatable diseases that often silently amplify or even masquerade as generalized geriatric frailty. • Discuss how patient-centered clinical decision making may be appropriately redirected when the patient, family, and physician agree that the patient is irreversibly quite frail. • Give specific examples of recommendations to a patient and family when advanced and irreversible frailty is identified. Frailty is a general term that has been applied to certain elderly folks for quite some time. The term brings to mind the image of a thin, stooped, slow-functioning 80- or 90-year-old. Although a precise and standardized definition of medical frailty is still a challenge, the simplest understanding is that frailty is a state of increased vulnerability to adverse outcomes.1 The most widely used definition in clinical practice was suggested by Fried et al. in 2001. This definition identifies frailty as the presence of three or more of the following five criteria: weight loss, exhaustion, weak grip strength, slow walking speed, and low physical activity.2 Some researchers and clinicians have suggested adding cognition, depressed mood, and pain to this list.3–5 A basic tenet of geriatrics has been that age itself is not a good predictor of outcomes. Frailty is not synonymous with either age or disease. However, the prevalence of frailty seems to increase with chronologic age, and there comes a functional point at which frailty becomes likely for all individuals, making them vulnerable to adverse outcomes.6 Even marathon runners who are in top physical shape tend to demonstrate an inevitable point at which physical reserves begin to deteriorate more rapidly. It is estimated that in people older than 85 years of age, approximately 70% show signs of frailty; of that age group studied, 49% were living in the community, and 21% were living in nursing homes.7,8 These frail, older patients often pose a challenge to their health care provider, who may feel overwhelmed by the complex presentation of the patients’ health status.3 One of the major hurdles is that frailty does not fit the traditional medical model of single diagnosis or single organ system disease. There is almost never a chief complaint, and the manifestations of system failure within frailty occur in combination. Frailty refers to notable clinical losses in reserve in many systems that are interdependent for good health.9–11 Consensus does not yet exist regarding the medical components of frailty.3,6,12 However, the term is increasingly recognized as progressively decreasing reserves in our aging population. The reserves of one system are no longer able to compensate for the decline in another system, as they do in the robust individual. Although the recognition of frailty in a patient should not lead to decreasing care, it does generate a cascade of care needs, such as increased physician visits, hospital admissions, emergency room visits, prescription medications, and ancillary services.1,8 Primary care clinicians are well poised to identify frail patients in their practices. By identifying the frail patient, focused interventions (or avoidance of interventions), goal setting, and recommendations about medical management (Tables 29-1 and 29-2) can be made with discernment. There is good evidence that identifying frail patients will improve clinical outcomes and there is also increasing evidence that it is cost effective—in short, it is good medical care.3,13,14 TABLE 29-1 Clinical Assessment and Management of Common Frailty Symptoms It has been proposed that aging is an accumulation of random damage to a complex system with overlapping parts. As defects accumulate with time, the organism loses its redundancy across multiple molecular, cellular, and physiologic systems.15 Resilience is lost—systems no longer have the ability to compensate for one another. The individual then becomes frail as the decline in a majority of systems results in a negative energy balance, sarcopenia, and diminished strength and tolerance for exertion.16 All systems are at or near the threshold of failure and homeostasis becomes difficult. Recently, frailty has been viewed as a manifestation of an impaired energy pathway.17 In other words, as persons become frail, more energy is needed to maintain homeostasis. Any pathology rapidly decreases the energy available in the system for healing, making the patient more vulnerable. In short, homeostasis becomes harder to maintain and the body becomes much less forgiving. Within disciplines focusing on care and service to the aged individual, there has been a lively discussion for at least the past two decades about whether or not the term can be used to identify a subset of older people who deserve closer clinical monitoring and support.18 Various models of frailty have been proposed to predict the risk of poor clinical outcomes. The most well-known and widely used model, as discussed in the previous section, was proposed by Fried et al. in 2001 and describes frailty as a phenotype—a clinical syndrome or set of signs and symptoms that tend to occur together, thus characterizing a specific medical condition.2 Components of the phenotype include the following five conditions: unintentional weight loss, exhaustion, weak grip strength, slow walking speed, and low physical activity. The presence of three or more of these factors equals frailty. In addition to assessing physical function, many clinicians believe that the definition of frailty should also include cognition, depressed mood, pain, and perhaps even advanced age. Another popular model of frailty was proposed by Rockwood et al. in 2007.9,19 In this model a frailty index (FI) is obtained—basically by adding all the multisystem biomarkers of decline together (disabilities and comorbidities) and coming up with a number. This concept views frailty as an accumulation of deficits—a quantitative approach using the number of health problems rather than the nature of health difficulties. Each of these models, as well as other descriptions, has its own strengths and weaknesses. Although useful in research and policy planning, neither approach, to this point in time, has significantly benefited the primary care clinician. A simple, clinical, useful tool for frailty that will improve care and value patient-centered outcomes is still to be developed.5,6 Frailty has clinical consequences. It is widely accepted that recognizing frailty is important clinically, but recognizing physical frailty in clinical practice may not be as straightforward as first thought.1,20 Many patients and families, as well as clinicians, may simply attribute declines in function to “old age” and not recognize frailty as an entity. Because of the often slow gradual decline, medical attention may not be sought. Other conditions, such as chronic disease, comorbidities, and disability, may overshadow the recognition of frailty. Also, there is often a general feeling that there is no treatment or intervention that is going to help with frailty anyway.21 Timely recognition of frailty by the clinician may enable early identification of potentially treatable underlying conditions or open the possibilities of prevention and treatment. Primary care services for the oldest old are often reactive, and may not prove to have a significant impact on mortality or quality of life.1 Identifying the frail patient may result in more proactive, preventive, or anticipatory clinical therapy decisions. Clinicians can potentially identify frail older adults by asking their older patients about declines in strength, endurance, nutrition, physical activity, fatigue or decreased energy, or slowed performance. Physical findings may include weight loss, slowed gait speed, and weakness.

Frailty

Symptom

Assessment

Treatment

Unintentional weight loss

Measure weight loss in the previous 6 months/year as a percentage of previous body weight (significant loss is >5%)

Ask: “Have you lost more than 10 lbs in the past year—not on purpose?”

Inquire about food availability, preparation, and social aspects of eating

Assess for dental problems

Liberalized diet (encourage foods of choice)

Recommend small frequent feedings

Consider nutritional supplements

Exhaustion

Ask: “How often in the past week did you feel exhausted?”

“How often would you say you just could not get going?”

Medication review to eliminate fatigue-causing medications

Reordering tasks to conserve energy (e.g., eating first, resting, then bathing)

Treat remediable conditions (COPD, CHF, anemia, insomnia)

Modify daily procedures (e.g., sitting while showering rather than standing)

Weakness/low physical activity

Ask: “How often last week did you feel everything was an effort?”

Measure grip strength (Jamar handheld dynamometer)

Increase physical activity (e.g., walking 20-30 min, 3-5 times per week)

Strength training

Modify environment to decrease energy expenditure (e.g., placement of phone, bedside commode)

Adjust room temperature to patient’s comfort

Slow walking speed

Timed walking at usual pace

15 feet: slow is >6 seconds for person of normal height (7 seconds for females under 62 inches and males under 68 inches)

Recommend referral for rehabilitation evaluation or physical therapy for strength training

Recommend tai chi if available

Cognition

Mini-Cog screening

MMSE, SLUM, or similar testing

Exclude reversible causes (medication toxicity, metabolic changes, depression, thyroid disease, subdural hematoma, etc.)

Promote brain health by exercise, diet, stress reduction, etc.

Nonpharmacologic interventions (behavior modifications, scheduled toileting, music, bathing in AM)

Maximize and maintain functioning

Mood

Screen for depression (Geriatric Depression Scale, PHQ-9, etc.)

Assess for helplessness, hopelessness, lack of pleasure, guilt, loss of self-esteem, social withdrawal, persistent dysphoria, and suicidal ideation

Prescribe SSRI alone or in combination with cognitive-behavioral therapy

Schedule frequent encounters

Listen to concerns

Generally avoid TCAs in older adults

Consider ECT if severe

Pain

Assess pain severity on scale of 1 to 10

Ask: “Describe how pain has interfered with your activities during the past 24 hours.”

Educate on nonpharmacologic approaches to pain management (clean safe environment, decreased stimuli, back rub, therapeutic touch, etc.)

If needed, prescribe oral analgesics for chronic and breakthrough pain in appropriate dosages—short-acting q3-4 hours; long-acting q8-12 hours (Initiate a stimulant laxative in all patients receiving opioids)

Etiology of frailty

Models of frailty

Is recognition of frailty helpful to the clinician?

Frailty