Chapter 12

Fractures and back pain

Fractures

Introduction

Five percent of falls in the older adult will result in a fracture. About 40–50% of older women and 13–22% of older men will experience a hip, vertebral or forearm fracture in their lifetime (1). The high risk of morbidity and mortality after an osteoporotic fracture demands a multidisciplinary approach to prevent fracture complications, assess and address the reasons for the initial injury and rehabilitate to pre-injury function. This process should commence as soon as possible after the older patient arrives in the emergency department.

Definition and background

A fragility fracture results from mechanical forces that would not ordinarily result in a fracture, known as low-energy trauma (2), such as falling from a standing height or less. Fragility fractures occur most commonly in the proximal femur, vertebrae and distal radius, as well as the humerus, ankle, pelvis and ribs. Fractures are more common in the older population due to the increased incidence of falls (Chapter 8) and osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis is the reduction in bone density and disruption in bone architecture that renders the bone more fragile and liable to break. Diagnosis is made clinically, with the presentation of a typical fracture, such as hip, vertebra or distal radius or with bone density (DEXA) scanning. Risk factors for osteoporosis include age, family history, steroid use, alcohol and smoking, immobility, renal failure and endocrine disorders.

Other risk factors for fractures include osteomalacia due to vitamin D deficiency, Paget’s disease and primary and secondary malignancy.

Initial assessment

The initial priorities in the management of a patient with a suspected fracture are highlighted in Box 12.1.

Hip fractures

A fracture of the proximal femur is the commonest fracture in the older adult, with huge implications for the individual patient and health services alike.

Hip fracture is associated with a mortality rate of 10% at 1 month and 30% at 1 year, and up to 30% of those admitted from their homes subsequently require institutional care. This often reflects comorbidities resulting in a fall and post-operative medical and functional complications, and is less often due to the fracture or the operative process itself.

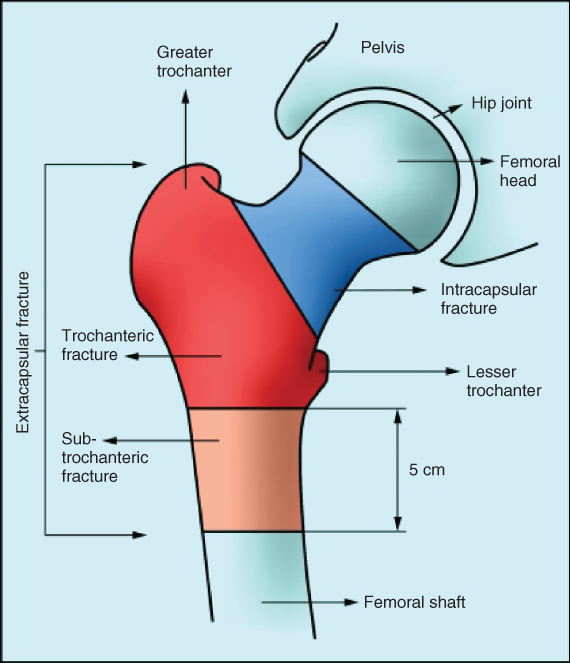

Hip fractures occur between the edge of the femoral head and 5 cm below the lesser trochanter, and can be classified into intracapsular, intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric (Figure 12.1). This distinction influences operative management but basic emergency care is unchanged. Prompt operative fixation is associated with reduced mortality, decreased post-operative pain, early mobilisation, and reduced length of hospital stay and major complications (3). Surgical intervention is the best form of analgesia and is undertaken in the vast majority of patients, even in cases of severe frailty or terminal illness. Surgery should ideally take place on the day of or day after the fracture.

Figure 12.1 Classification of hip fractures.

Source: From Parker M, Johansen A. Hip fracture. BM J. 2006 Jul 1;333(7557):27–30. Reproduced with permission of BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

History and examination

Hip fractures can result from relatively minor trauma and in some cases no history of injury is provided, especially in patients with delirium or dementia. A high index of suspicion should be assumed in any older person with new immobility or who is ‘found on the floor’. Patients may not volunteer experiencing pain in the hip: pain may only be present on movement or may radiate to the knee, groin or lower back.

On examination, the leg may be shortened and externally rotated. There may be tenderness over the greater trochanter or in the groin. Remember that a fall may result in multiple injuries and the initial approach should be similar to that described in Chapter 11.

Investigations

Radiographs

Standard imaging is an anterior–posterior and lateral radiograph. If the proximal femur appears normal, check for pubic rami, acetabular or sacral fractures. Radiographs should be inspected closely for disrupted trabeculae and breaches in cortical continuity, Shenton’s line and the neck-shaft angle. Shenton’s line is formed by the medial edge of the femoral neck and the inferior edge of the superior pubic ramus and lack of contour is suggestive of a fractured neck of femur. The neck-shaft angle should be 120–130°, determined by measuring the angle of the lines drawn through the centres of the femoral shaft and the femoral neck.

If the radiograph appears normal

An undisplaced intracapsular fracture occurs in 15% of cases and may not be visible on plain radiographs. An AP film centred on the hip may confirm a fracture, but if it appears normal and there is still a clinical suspicion of fracture further imaging is required. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is the most sensitive imaging modality for detecting occult hip fractures, and it also identifies alternative pathology such as pelvic fractures, psoas abscess, haematoma, and significant soft tissue injuries (4). If MRI is not available promptly or is contraindicated, CT (computed tomography) is recommended (5).

Chest radiograph

This is usually requested simultaneously to hip radiographs to screen for chest pathology as a cause or consequence of fall and to assist pre-operative anaesthetic assessment.

Blood tests

Full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function and blood typing and coagulation should be requested.

Electrocardiogram

An ECG may identify a trigger for the injury such as ischaemia or complete heart block, and will identify any issues requiring intervention prior to anaesthesia.

Echocardiogram

An echocardiogram may be required if the patient demonstrates signs of valvular heart disease but in many cases will not change management and should not result in a delay to surgery.

See Table 12.1 for further discussion on investigations in hip fracture patients.

Table 12.1 ‘HEADACHES’: factors to consider pre-operatively in fractured neck of femur

| H | Heart | Consider an urgent echocardiogram if there are signs or symptoms of severe aortic stenosis or severe undiagnosed left ventricular failure. Avoid delaying surgery where possible If the patient has a pacemaker, get this checked if there is any evidence that failure might have been the cause of the fall |

| E | ECG | Observe for concerning features requiring intervention or urgent cardiology review:

|

| A | Anaemia | Note haemoglobin and platelet count and arrange transfusion if required |

| D | Drugs | Withhold ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, oral diuretics and oral hypoglycaemics prior to surgery. Intravenous diuretics can be used as required. Consider stopping or reducing antihypertensives. Stop NSAIDs. Maintain any chronic corticosteroids, adding a stress dose peri-operatively. Continue anti-Parkinson’s drugs, antidepressants and beta-blockers (unless the blood pressure is low) |

| A | Anticoagulation | If the patient is taking anticoagulants, consider whether the patient is at high risk (e.g. valve replacement) or lower risk (e.g. recurrent DVT, AF). Reverse INR with vitamin K and consider an IV heparin infusion or SC low molecular weight heparin. Consult with haematology if necessary |

| C | Chest | Examine for signs of chest infection or lung disease, which may complicate anaesthetic management. Look at the chest radiograph for these features |

| H | Hyperglycaemia | A dextrose infusion and insulin sliding scale may be necessary pre-operatively in diabetic patients normally on insulin. Blood glucose should be monitored closely and the patient placed at the start of the theatre list |

| E | Electrolytes and fluid balance | Exclude severe hypokalaemia, acute hyponatraemia or acute kidney injury Patients are usually dehydrated on admission: check volume status and give intravenous fluids. Exclude urinary retention |

| S | Mental status | Assess for pre-existing dementia, delirium and decision-making capacity |

ACE, angiotensin-converting-enzyme; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; AF, atrial fibrillation; INR, international normalized ratio.

Management

Management in the ED should be in accordance with the general management of fractures highlighted in Box 12.1, with a focus on relieving pain and preparing for surgery.

Pain should be assessed immediately on presentation to the ED and within 30 minutes of analgesia being given, and then at hourly intervals or more frequently as indicated (5).

To avoid reliance on opioids with their frequent side effects in the older patient, consider providing regional anaesthesia as the first-line method of pain control in patients presenting with a fractured neck of femur (6, 7). The most common procedure offered is a fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB) described below.

Contraindications to FICB include patient refusal, anticoagulation, previous femoral bypass surgery, inflammation or infection over the injection site, or an allergy to local anaesthetics. If any of these contraindications is present; there is no appropriately skilled clinician available or pain is still poorly controlled; intravenous opioids, e.g. IV morphine, are usually required in small doses, repeated if required. (See Chapter 3 for a discussion about analgesia in the older patient.) Ensure that regular and as required analgesia is prescribed.

Fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB)

FICB is an effective, safe and easy-to-learn procedure, which can be performed at the bedside in the ED without a need for a nerve stimulator. It may be undertaken with or without ultrasound guidance.

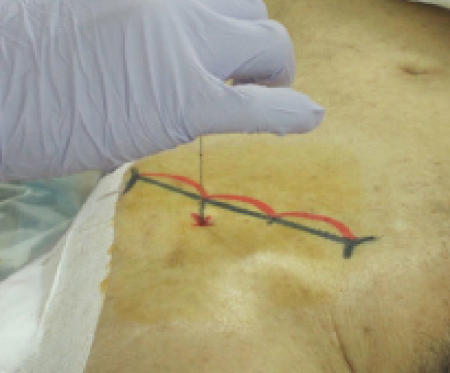

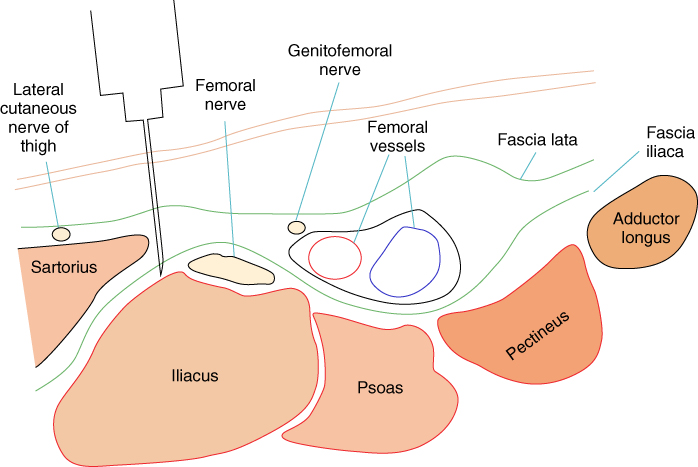

An injection of local anaesthetic into the fascia iliaca compartment aims to block the femoral nerve, lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh and obturator nerve, and provides effective analgesia in proximal femoral fractures (8). See Box 12.2 and Figures 12.2 and 12.3 for further explanation.

Figure 12.2 Surface anatomy of FICB. Source: From Fujihara Y, Fukunishi S, Nishio S, Miura J, Koyanagi S, Yoshiya S. Fascia iliaca compartment block: its efficacy in pain control for patients with proximal femoral fracture. J Orthop Sci. (9) Sep 1;18(5):793–7 (9).

Reproduced with permission of Springer.

Figure 12.3 Anatomy of the fascia iliaca compartment block.

Source: From Shiv Kumar Singh and S. M. Gulyam Kuruba. The Loss of Resistance Nerve Blocks. ISRN Anesthesiol. (10). (10) Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

Facilitating surgery

Hip fracture patients are medically complex. Nearly half of hip fracture patients have dementia, and a majority will develop significant complications such as delirium, acute kidney injury, and lower respiratory tract infection. Evidence suggests that early (ideally pre-operative) involvement of a geriatric medicine team specialising in orthogeriatrics improves outcomes. The NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) provides guidance on management of hip fractures from admission to discharge (5).

Table 12.1 highlights important aspects to consider when preparing a patient with a hip fracture for theatre from the ED.

Ongoing care

Postoperatively, the patient should receive multidisciplinary care, ideally on a designated ortho-geriatric ward. Table 12.2 lists areas of focus in the rehabilitation process. It is important to have awareness of these issues in the ED, as the preparation for discharge should begin from the time of admission.

Table 12.2 Considerations in the ongoing care of a patient with a fragility fracture (2)

| Analgesia | Prescribe regular non-opioid and PRN opioid analgesia. NSAIDs are not recommended. Oxycodone may be preferred over morphine and codeine because of the high rates of acute and chronic kidney injury in these patients |

| Mobilisation | Aim to mobilise as soon as possible postoperatively with physiotherapy input if there are no orthopaedic contraindications |

| Prevent surgical site infections | Give antibiotics immediately preoperatively and for a limited duration postoperatively. Inspect the wound as per protocol |

| Protect pressure areas | See Chapter 8. Ensure regular skin inspections, a pressure-relieving mattress and heel protection |

| Prevent of venous thromboembolism | If there are no contraindications, prescribe pharmacological prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin or a factor Xa inhibitor and mechanical prophylaxis with compressive stockings |

| Rationalise drug treatment | Eliminate unnecessary medications to prevent complications associated with polypharmacy |

| Protect the urinary tract | Avoid catheterisation if at all possible – it increases risk of infection and impairs mobility. Check frequently for urinary retention |

| Prevent constipation | Regular stool softeners and laxatives should be prescribed |

| Prevent delirium | Monitor closely to detect any postoperative complications early. Optimise environmental factors, e.g. surroundings, orientation and lighting, hearing and visual aids. See Chapter 18 |

| Assess cause of original fall | See Chapter 8 |

| Treat osteoporosis | Most patients should be treated with a bone protection agent, calcium and vitamin D to prevent further fractures |

| Provide nutritional support | Assess risk of malnutrition, and use supplements if indicated |

Pelvic insufficiency fractures

Pelvic fractures account for 7% of all fragility fractures (11) and carry a mortality risk similar to that of hip fractures at 1 year post injury (12). They are associated with significant loss of independence, with only 39% returning to their pre-injury level of function at 1 year in one study (13).

Pelvic fractures commonly present with a lateral compression type fracture pattern, resulting from a fall from standing onto the side. In two-thirds of cases this results in stable fractures of the pubic rami (14). However, 50% of pubic rami fractures are associated with an additional fracture of the posterior pelvic ring, such as an iliac wing fracture or sacral insufficiency fracture, which is often missed on plain radiography. Most of these remain stable, and heal well with non-operative treatment but the time for recovery of symptoms may be much longer than expected. A small proportion of these posterior pelvic ring fractures are unstable and may require operative intervention (15). Fractures of the lumbar vertebrae or acetabulum may also be missed.

History, examination and investigations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree