Forequarter Amputation

Jacob Bickels

Yehuda Kollender

Martin M. Malawer

BACKGROUND

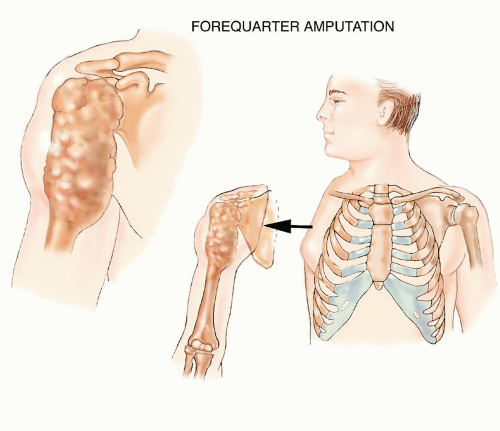

Forequarter amputation (interscapulothoracic amputation) entails en bloc removal of the upper extremity together with the scapula and the lateral aspect of the clavicle (FIG 1). This mutilating amputation of the upper extremity was traditionally done for high-grade sarcomas around the proximal humerus and scapula.1,3,6,7,8,9

Tumor response to chemotherapy and radiation therapy and the option of endoprosthetic reconstruction have made these procedures rare, and limb-sparing resections are safe alternatives in 90% to 95% of these cases.2

ANATOMY

The upper extremity and scapula are attached to the upper torso and chest wall by soft tissue elements (rhomboid, levator scapulae, trapezius, pectoralis major and minor, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and serratus anterior muscles) and a single bone (clavicle). They all must be transected to allow the performance of a forequarter amputation.

The axillary vessels and infraclavicular portion of the brachial plexus pass just inferiorly to the coracoid process, which is easily palpable, and lie below the deltopectoral fascia. These structures should be evaluated prior to surgery in order to determine the segment that can be safely transected and ligated, especially because large tumors may come close to the thoracic outlet.

Large tumors of the periscapular area may easily extend into the posterior triangle of the neck, the adjacent paraspinal muscles, and the underlying chest wall. Tumor extension into these anatomic sites must be carefully evaluated prior to surgery because en bloc resection of a chest wall segment or a concomitant neck dissection may be required.

INDICATIONS

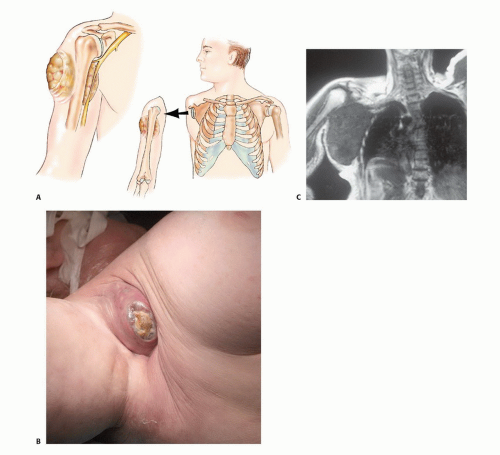

Large soft tissue tumor around the proximal arm/axilla with neurovascular encasement and compromise and extension across the joint (FIG 2)

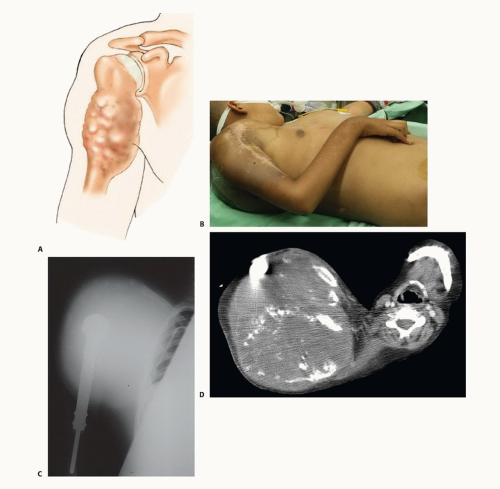

Large bone tumor (primary bone sarcoma or metastatic lesion) of the proximal humerus and scapula with extensive soft tissue component and invasion into the shoulder joint and surrounding muscles (FIG 3)

Extensive locoregional tumor recurrence around the shoulder girdle (FIG 4)

Palliation of intractable pain or tumor fungation, associated with a rapidly enlarging lesion that has not responded to chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy

Forequarter amputation is usually contraindicated when the tumor extends to the chest wall or to the posterior triangle of the neck and paraspinal muscles.

IMAGING AND OTHER STAGING STUDIES

The combined use of computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows determination of the extent of bone and soft tissue tumor involvement and

thus estimation of the potential size of the soft tissue margins, that is, at the neck, paraspinal muscles, and chest wall.

Angiography is extremely helpful in locating the anatomic position of the axillary and/or brachial vessels and in evaluating whether these structures are involved by tumor. Physical anomalies (eg, a duplicate axillary artery) can occasionally be identified as well. Angiography also makes it possible to accurately determine the best level of ligation of the axillary vessels.

No imaging studies can precisely distinguish whether the brachial plexus is infiltrated by tumor or whether the vessels and plexus are simply displaced, and they provide only indirect evidence of tumor extension to the nerves. On the other hand, we have found venography of the axillary veins to be a simple and accurate method of determining brachial plexus involvement.

A brachial venogram will show complete obstruction of the main axillary veins when tumor is infiltrating the brachial plexus, whereas it will show venous patency and displacement when a tumor is adjacent to, but not infiltrating, the plexus.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Position

The patient is placed in a full lateral position and is secured to the operating table at the hips with tape.

Alternatively, a VAC pack can be used to secure the torso.

An axillary roll is placed under the axilla to allow full excursion of the chest, and a sponge-rubber pad is placed under the hip to prevent ischemic damage to the skin in this area.

The skin is prepared in the usual manner, and the tumorbearing extremity is draped free (FIG 5).

FIG 3 • A. Illustration showing high-grade sarcoma of the proximal humerus with tumor extension across the joint and around the scapula. B. Intraoperative photograph of a 15-year-old patient who was diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma of the proximal humerus and treated with preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The tumor grew considerably despite treatment, causing extensive destruction of bone and extension into the surrounding soft tissues as evidenced by the (C) plain radiograph and (D) CT.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|