Chapter 14

Food Hypersensitivity

Rosan Meyer and Carina Venter

Introduction

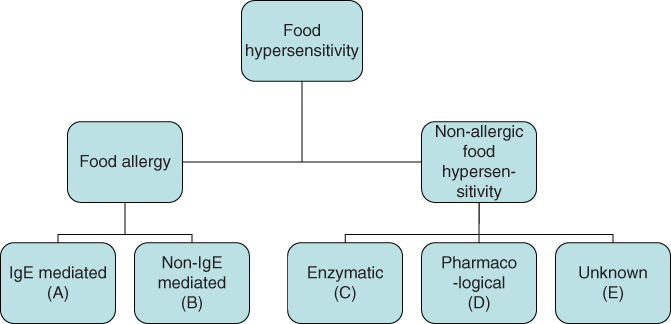

Many symptoms are correctly or incorrectly attributed to food hypersensitivity and as a result can lead to confusion when it comes to diagnosis and management. In an effort to improve diagnosis, treatment and general understanding of allergic reactions the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization issued a report proposing revised nomenclature [1]. This report states that any reaction to food that causes objectively reproducible symptoms or signs, even when the food is eaten unknowingly (blind), should be described as food hypersensitivity. If immunological mechanisms can be demonstrated then the reaction can be described as a food allergy. If immunoglobulin E (IgE) is involved in the reaction then the term IgE mediated food allergy should be used and the term non-IgE mediated food allergic reactions used for immune mediated reactions that are not mediated by IgE. All other reactions should be described as non-allergic food hypersensitivity, as there is no immunological mechanism involved (Fig. 14.1).

Figure 14.1 Classification of food hypersensitivity (adapted from Johansson et al. [1]).

Important factors concerning food hypersensitivity reactions

- A food hypersensitivity reaction is known as a food allergy where the immune system is involved. These reactions may involve immunoglobulin IgE or may involve other immune mechanisms (non-IgE mediated food allergy) (Fig. 14.1, A and B).

- Some food hypersensitivity occurs as a result of enzyme deficiency such as lactase deficiency or disorders of amino acid or intermediary metabolism, e.g. phenylketonuria. These reactions are non-allergic hypersensitivities, are well documented and are discussed elsewhere in this book (Fig. 14.1, C).

- Some foods may cause unpleasant symptoms, e.g. caffeine in coffee and cola; vasoactive amines in cheese and wine; phenylethylamine in chocolate. These effects are pharmacological and are non-allergic (Fig. 14.1, D).

- Some food induced reactions are non-immune mediated and of unknown origin. These may include a variety of gastrointestinal symptoms related to different foods, e.g. abdominal cramping with garlic or wheat fibre (Fig. 14.1, E).

Over recent years a significant amount of research has been undertaken in this area. This chapter can only provide an introduction to food hypersensitivity and further reading is recommended (see References and Further reading). Dietetic principles have been concentrated on, but it is essential to understand some of the immunological mechanisms involved to ensure dietetic management is optimal.

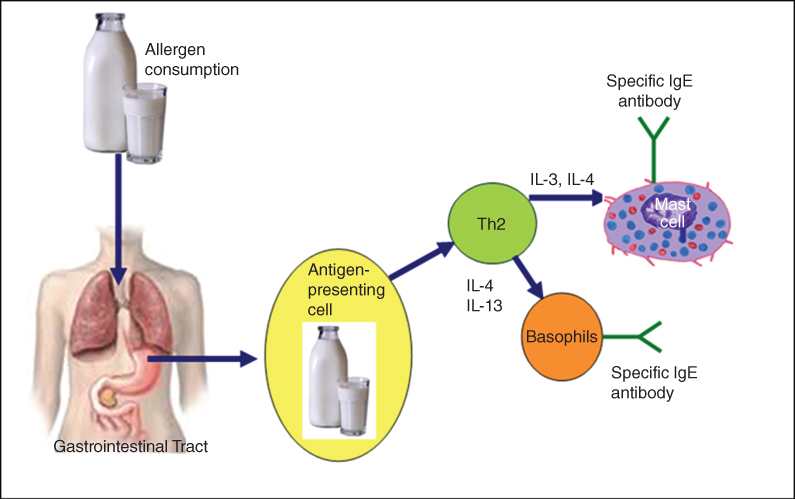

IgE mediated allergy

IgE is an immunoglobulin normally present at very low levels in the plasma of non-allergic individuals, but levels are raised in patients suffering from allergic conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and anaphylaxis. When atopic individuals are exposed to a food protein (antigen) via the skin, gastrointestinal tract or lung mucosa, the antigen is taken up and transported to local lymph nodes by specialist processing cells called antigen presenting cells. These cells break down and present the antigen to T and B cells within specific areas of the lymph node. The type of T cell involved in this encounter is important in determining whether IgE [as opposed to other antibody isotypes (IgA or IgG)] is produced. T-helper 2 cells play an important role in determining IgE production by B cells. These surround the antigen and present the antigen to T-helper 2 cells. This stimulates B cells to produce IgE specific antibodies, which then bind to mast cells or basophils via high affinity receptors. This cascade of immune reactions then leads to the symptoms associated with an immediate food allergy (Fig. 14.2). A variety of cytokines are released which may induce the IgE mediated late response. Neutrophils and eosinophils invade the site of response and infiltrated cells are activated. These then release a variety of mediators including platelet activating factor, peroxidase, eosinophil major basic protein and eosinophil cationic protein leading to a second phase allergic response that is often more severe than the initial response. In the subsequent 24–48 hours, lymphocytes and monocytes infiltrate the area and establish a more chronic inflammatory picture [2].

Figure 14.2 Immunological basis for food allergy.

Clinical manifestation of IgE mediated food allergy

Symptoms generally appear within 0–2 hours after a small amount of food has been consumed. Immediate symptoms may affect the gut, the skin and/or the lungs and common symptoms are summarised in Table 14.1 [3].

Table 14.1 Symptoms of food allergy modified from Sackeyfio et al. [24] with permission from NICE [10]

| IgE mediated Immediate onset | Non-IgE mediated Delayed onset | |

| Gastrointestinal | Angioedema of the lips, tongue and palate | Reflux |

| Oral pruritis | Abdominal pain, bloating | |

| Nausea | Vomiting | |

| Colicky abdominal pain | Gastro-oesophageal reflux | |

| Vomiting | Loose frequent stools | |

| Diarrhoea | Blood and/or mucus stool | |

| Infantile colitis | ||

| Food refusal/aversion | ||

| Constipation | ||

| Perianal redness | ||

| Pallor and tiredness | ||

| Faltering growth and one or more of the gastrointestinal symptoms above (with or without serious atopic eczema) | ||

| Cutaneous | Acute urticaria | Pruritis |

| Acute angioedema | Atopic eczema | |

| Erythema | Erythema | |

| Pruritis | ||

| Respiratory | Upper respiratory tract symptoms (nasal itching, sneezing, rhinorrhoea) | Asthma |

| Lower respiratory tract symptoms | ||

| (cough, chest tightness, wheezing or shortness of breath) | ||

| Systemic | Anaphylaxis |

Symptoms of upper airway obstruction (laryngeal oedema), lower airway obstruction (broncho-constriction), hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias and even heart failure constitute the most severe and sometimes life-threatening reactions. This is known as anaphylactic shock and first symptoms may include sneezing and a tingling sensation on the lips, tongue and throat followed by pallor and feeling unwell, fearful, warm and light-headed. The presentation of anaphylaxis is varied but the major causes of death are obstruction to the upper airway or shock, hypotension and cardiac arrhythmia [4–6]. The results of double blind placebo controlled food challenges (DBPCFC) from several studies in the USA and UK have shown that the most common foods to provoke immediate reactions are peanuts, tree nuts, milk, egg, soy and wheat, fish and shellfish. Seeds (e.g. sesame) may also cause this type of reaction.

Non-IgE mediated food allergy

These reactions are immune mediated delayed hypersensitivity reactions with symptoms appearing more than 2–48 hours after antigen exposure. Although the mechanism of this reaction is not yet fully understood, it is thought that it involves sensitised T cells reacting with the antigen to produce cytokines, which mobilise non-sensitised cells to fight the antigen. This causes inflammation, tissue damage and the formation of epitheloid and giant cells [7].

Clinical manifestation of non-IgE mediated food allergy

These reactions to foods may develop slowly after hours or days and the exposure dose evoking a reaction varies from small to larger amounts [8, 9]. As with immediate symptoms, adverse reactions can affect the skin, gastrointestinal tract or lungs. Symptoms include chronic diarrhoea, vomiting which in severe persistent cases may lead to hypovolaemic shock, diarrhoea abdominal pain, faltering growth, infantile colic, constipation, eczema and asthma [10]. Gastrointestinal symptoms are further discussed in Chapter 7.

Mixed IgE and non-IgE food allergy

It is now recognised that patients can present with a mixed picture including both the immediate type IgE mediated and the delayed type non-IgE mediated reactions. An example of this overlap is atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic oesophagitis [11, 12]. The same child may show signs of both IgE mediated allergy, e.g. to egg, and non-IgE mediated allergy, e.g. to milk [13].

Symptoms often associated with both IgE and non-IgE mediated food allergy

It is important to recognise additional features that are often present in children with food allergies and these may have implications in the nutritional management. These include faltering growth; vitamin D, calcium and iron deficiency; aversive feeding; pallor and tiredness [14, 15].

Non-allergic food hypersensitivity

The most well known non-allergic food hypersensitivity is lactose intolerance (p. 124). Symptoms arise due to the osmotic effects of lactose and fermentation thereof by intestinal bacteria. This may cause excessive flatus, explosive diarrhoea, perianal excoriation, abdominal distension and pain [16]. The overlap in symptoms with non-IgE mediated gastrointestinal food allergies often causes confusion with the diagnosis, but is distinctly different due to the absence of an immunological mechanism.

More controversial problems which may be related to non-allergic food hypersensitivity are migraine, rheumatoid arthritis, migraine with epilepsy, enuresis, autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Dietary manipulation (elimination and challenge) is the mainstay for diagnosis and treatment of these conditions [2]. It is important to consider nutritional adequacy when such a diet is implemented (p. 320).

Diagnosis of food hypersensitivity

IgE mediated allergy

Skin prick tests

The skin prick test (SPT) indicates the presence of allergen specific IgE. It can be performed in a medical setting equipped to deal with anaphylaxis and yields an immediate result, which is very useful for clinicians and parents. Drops of food extract, positive (histamine) control and negative (saline) control are applied using lancets. In general, food allergens eliciting a wheal size at least 3 mm larger than those induced by the negative control are considered positive. Venter et al. provide more specific information on ‘cut-off points’ for SPT results [17]. It is important to note that the positive predictive accuracy of SPTs is less than 50% compared with results from DBPCFC. Negative predictive accuracy is 95% [18, 19]. This means that negative SPT responses are a worthwhile means of excluding IgE mediated allergies, but positive SPT responses only indicate an atopic individual with a tendency to react to this food. Exclusion diets should not be based on these results alone.

Specific IgE test

Specific IgE is an in vitro assay for identifying food specific IgE antibodies from serum. It is more expensive than SPT and the results are not available to the clinician immediately, possibly delaying diagnosis. This test may be preferred when patients have dermatographism, severe skin disease or a limited surface area for testing (e.g. in severe atopic dermatitis); when patients have difficulty discontinuing antihistamines; or when patients have exquisite sensitivity to certain foods [18]. Interpretation of results is as difficult as with SPTs. For more information on the interpretation of specific IgE see Venter et al. [17]. However, SPTs and specific IgE tests provide useful contributory information towards a diagnosis when added to the clinical history and are interpreted by clinicians with appropriate competencies [18, 19].

Intradermal test

A report of the British Society for Allergy and Environmental Medicine with the British Society for Nutritional Medicine [20] and the recent USA guidelines [21] do not recommend the use of intradermal tests. Unacceptably high false positive rates as well as safety concerns, such as systemic reactions (including fatal anaphylactic responses), are associated with this allergy skin test [22].

Other diagnostic tests

To date there are no additional diagnostic procedures to those described above which can be recommended as useful tests in the diagnosis of IgE and non-IgE mediated food allergy. IgG testing has received a significant amount of attention in the lay press for assisting in the ‘diagnosis’ of non-IgE mediated reactions. The European Association for Allergy and Clinical Immunology [23], the American Academy for Allergy Asthma and Immunology and the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [24] advise against the use of this ‘test’ for diagnosing any type of food allergy due to lack of research and the concern that misinterpretation may lead to nutritionally incomplete diets. Other tests that have also been shown to be of no benefit in the diagnosis of food hypersensitivity include vega testing, hair analysis, cytotoxic test, kinesiology, iridology, electrodermal testing and sublingual provocative food testing [25].

Non-IgE mediated allergy

There are currently no validated in vitro or in vivo tests which can identify foods responsible for non-IgE mediated food allergies [26]. It has been suggested that atopy patch testing could be used to aid the diagnosis of non-IgE mediated food allergy; however, this has not been confirmed by studies. It may be that combining SPT with patch testing can improve the diagnosis, but there is insufficient data for the routine use of this test in non-IgE mediated allergy [21, 24, 27, 28]. Currently, the symptomatic improvement on an allergen exclusion diet, followed by a return of symptoms on allergen reintroduction or a food challenge remains the gold standard for diagnosing this food allergic condition [21, 29].

Non-allergic food hypersensitivity

As for food allergy, there is no proven test for the diagnosis of non-allergic food hypersensitivity. Advertised diagnostic methods such as applied kinesiology, hair tests or electrodermal tests were evaluated in a Consumer Association report [30, 31]. The verdict was that known allergies in individuals were not picked up, the services exaggerated the number of allergies and this could result in unnecessarily restricted and inadequate diets. The report suggests that people should not waste their money on these tests. Vega testing has also been assessed in a double blind study and was shown to be unable to accurately diagnose food hypersensitivity of any mechanism [32].

Elimination diets for diagnosis of IgE and non-IgE mediated food allergies

Sometimes clinical history and diagnostic tests give a strong indication as to the food(s) causing symptoms. In this case, advice on dietary exclusion is given to manage the symptoms and reintroduction of these foods into the diet will not occur until there is an indication that the allergy may have been outgrown. However, in some cases (particularly for non-IgE mediated food allergy and non-allergic food hypersensitivity) it may not be clear if particular foods are involved. It may therefore be necessary to first devise a ‘diagnostic’ elimination diet. Before this is embarked upon it is essential to consider whether the child/parent is sufficiently motivated and able to adhere to the diet. The length of time required on an elimination diet to confirm/refute a food allergy is poorly researched and may vary from 2 to 6 weeks. In the absence of any clear, well researched guidance, a decision on the period of elimination should be made for the individual and the following factors should be taken into account:

- type of suspected food allergy (IgE mediated symptoms tend to resolve faster than non-IgE mediated symptoms)

- frequency of symptoms

- degree of restriction of diet (i.e. one food versus many foods)

- nutritional status of the child

Any improvement of symptoms has to be followed by reintroduction or a challenge with the offending foods, resulting in reproducible deterioration and then recovery on re-elimination in order to confirm the presence of a food allergy. The NICE guidelines recommend that challenges for IgE mediated allergy should be performed in a clinical setting, and food challenges (food reintroduction) for delayed symptoms can be performed at home [10].

Phase 1: diagnostic elimination diet

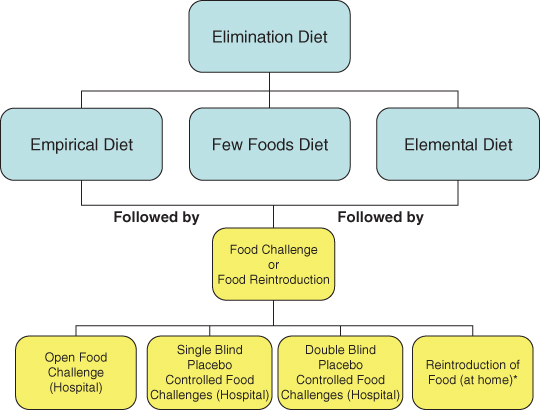

Taking a full diet history is mandatory before embarking on an elimination diet; this may indicate provoking foods. The accuracy of the diet history needs to be taken into account, as it is not uncommon for parents to be mistaken as to which foods affect their child and problems with staple foods eaten several times a day, such as milk and wheat, often go unnoticed [2]. Keeping a food symptom diary before starting a diet may provide a baseline but seldom adds any useful information about suspect foods which has not been revealed by diet history. The initial diet may exclude one food (e.g. cow’s milk) or a number of foods (e.g. cow’s milk, soya and eggs). The choice of diet is a matter of clinical judgement taking into account age, severity and type of symptoms and whether other elimination diets have already been tried [2]. There are three levels of dietary restriction: an empirical diet, a few foods diet or an elemental diet (Fig. 14.3).

Figure 14.3 Using elimination diets and food challenges/reintroduction to aid diagnosis.

* Only if there is no risk of an immediate severe reaction.

Empirical diet

An empirical diet is used where food hypersensitivity is suspected and causative agents are not known. One or several of the most commonly provoking foods are avoided. Cow’s milk, hen’s egg, wheat, soy, peanut, tree nut, sesame and kiwi are responsible for the majority of IgE mediated food induced allergic reactions in young children [2]. Fin fish, shellfish, tree nuts and peanut are more common food allergens in older children [2]. In children with atopic dermatitis (mixed IgE and non-IgE mediated) the offending foods are similar to those in IgE mediated allergies; however, studies of common allergens in delayed reactions yield anecdotal results. The most common foods in a paediatric population with non-IgE mediated gastrointestinal food allergies, according to Meyer et al., were milk, soy, egg and wheat [33]. It is not unusual for paediatric gastroenterologists to suggest a diet free from milk and soy (most cases) and egg and wheat in the more severe cases (Tables 7.8, 7.9, 7.10).

Many parents report allergic type symptoms related to fruit and occasionally to vegetables. It is important to elicit the type of reaction and also the time of year these occur. Pollen allergy syndrome (otherwise known as oral allergy syndrome) in older children may need to be ruled out [2]. In infants and young children citrus and tomato are often blamed for exacerbation of atopic dermatitis. Flare up of eczema may occur around the mouth/face due to the pH of the fruit and its histamine content, but specific research supporting this is absent. Fruit and vegetables contribute important micronutrients to the diet; it is therefore important not to eliminate these foods from a diagnostic exclusion diet without ensuring dietary adequacy. Practical advice is to cover the area around the mouth with petroleum jelly (e.g. Vaseline) prior to eating these fruits and vegetables.

Problems can occur with empirical diets when excluded foods are inadvertently replaced by others which can cause adverse reactions, e.g. a child on a milk free diet may drink soy milk or orange juice instead and it is possible to be equally reactive to these foods. Failure to respond to an empirical diet does not always therefore rule out the possibility of food hypersensitivity.

Few foods diet

A few foods diet is a diet consisting of a small number of hypoallergenic foods. This diet may be useful if there is a perception that most foods cause an allergic type reaction. Although it is often suggested as a dietetic option for establishing food induced hypersensitivity reactions, its use has only been extensively studied in patients with atopic eczema [34–36].

Diets using one meat, one carbohydrate source, one fruit and one type of vegetable have been used [37]. Examples of such diets are given in Table 14.2. If no improvement occurs with the first diet, a second diet containing a different set of foods can be used. Nutritional adequacy should be monitored carefully [2, 38, 39]. In extreme circumstances more rarely eaten foods such as rabbit, venison and sweet potatoes could be included [38]. As these diets are nutritionally demanding, it is suggested that they should not be followed for more than 4 weeks.

Table 14.2 Two examples of few foods diets

| A | B |

| Turkey | Lamb |

| Cabbage, sprouts, broccoli, cauliflower | Carrots, parsnips |

| Potato, potato flour | Rice, rice flour |

| Banana | Pear |

| Soya oil | Sunflower oil |

| Calcium and vitamins (Table 14.3) | Calcium and vitamins (Table 14.3) |

| Tap water | Tap water |

| Hypoallergenic formula (<2 years) | Hypoallergenic formula (<2 years) |

Possible additions: milk free margarine, sugar for baking.

Possible variations: bottled water; rabbit instead of above meats; peaches and apricots, melon, pineapple instead of above fruits.

Since the above diets are extremely rigorous, less restricted diets have been used to improve adherence (Table 14.3) [38]. It is much more difficult to find a completely different set of foods for a second attempt if the first is not helpful. However, it is possible to monitor progress closely and adjust or further restrict the diet during the third or fourth week in an attempt to achieve eventual success.

Table 14.3 Less restricted few foods diet

| This diet should be used for no more than 4 weeks. Children under 2 years require a nutritionally adequate substitute for milk | |

| Choose two foods from each food group | |

| Meat | Lamb, rabbit, turkey, pork |

| Starchy food | Rice, potato, sweet potato |

| Vegetables | Broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, sprouts (brassicas) |

| Carrots, parsnips, celery | |

| Cucumber, marrow, courgettes, melon | |

| Leeks, onions, asparagus | |

| Fruit | Pears, bananas, peaches and apricots, pineapple |

| Also included | Sunflower oil, whey free margarine |

| Plain potato crisps | |

| Small amount of sugar for baking | |

| Tap or bottled water | |

| Juice and jam from allowed fruits | |

| Salt, pepper and herbs in cooking | |

| A calcium (350–500 mg/day) and vitamin supplement is advisable for children who are not consuming a hypoallergenic formula: calcium gluconate effervescent 1 g × 3 daily; or calcium lactate 300 mg × 6 daily; or Sandocal 400 g × 1 tablet daily; or Calcium Sandoz liquid 15 mL daily; Dalivit/Abidec 0.6 mL daily | |

The acceptability of the few foods diet depends greatly on the dietitian’s advice regarding planning menus, giving ideas for meals and providing recipes for cooking with the allowed foods. Ideas for packed lunches should be given as school canteens cannot be expected to cope with such a restricted diet. For vegetarians a larger range of vegetables, including pulses, would be allowed. The dietitian should keep in regular contact with the family to ensure adherence and nutritional adequacy of the diet. The cost of the diet may be a problem and should be discussed with the family.

The few foods diet is most difficult to carry out in the toddler age group. Such children may still be very reliant on milk or formula for their nutrition. Ideally they should take a suitable hypoallergenic formula, but it may be refused due to its taste. The diet can be altered to suit the individual child and, in some circumstances, can be made less restricted by including a larger range of meats, fruits and vegetables.

Few foods diets are usually carried out in the home environment. It is important that the child’s lifestyle is not altered; otherwise changes in symptoms could be attributed to factors other than change in diet. Regular medication should not be changed before or during the diet trial for the same reason. Children on regular medication such as anticonvulsants should remain on these but be switched to a colour/preservative free version if possible. Attention should be paid to non-food items which may be consumed by small children such as toothpaste (a white toothpaste should be used), chalks and play dough [38].

Elemental diet

Hypoallergenic or elemental diets based on amino acids (e.g. Elemental 028 Extra, Neocate Advance for children or Neocate LCP, Nutramigen AA for infants) can occasionally be justified where there has been no response to a restricted diet, but this treatment should be very much a last resort as suitable products are very unpalatable and tube feeding may be necessary to achieve adequate nutrition. This will involve a hospital admission. Suitable products are listed in Tables 7.7 and 7.11. These feeds have been used mainly for children with severe atopic dermatitis and for severe gastrointestinal food allergies [29, 36, 38].

Phase 2: food challenges and reintroduction foods

Following improvement on the diagnostic diet, the dietitian will need to perform either a food challenge in hospital, in particular for IgE mediated symptoms, or a reintroduction plan/prolonged food challenge at home for the delayed type reactions.

Food challenges

History taking

Prior to considering any food challenge it is important to gather all the history relevant to performing the challenge safely. Taking a history will provide important information on

- the age of the patient to determine how difficult it may be to perform the food challenge and to help in identifying the possible food causing the symptoms

- the type of food or foods causing reported symptoms, e.g. raw egg versus cooked egg

- the age of onset of symptoms as well as the frequency and reproducibility of the reaction

- the time of onset of symptoms in relation to food consumption; the clinical manifestation and duration of the symptoms

- the quantity of food causing symptoms in order to prevent false negative food challenges

- a thorough description of the most recent reaction is also very important in designing challenges; the details of the most recent reaction may be more helpful than those of more distant reactions

- sometimes more than one food or factor is needed to elicit a positive challenge outcome (e.g. a combination of foods eaten together, exercise induced anaphylaxis or with concomitant drug intake)

- a list of foods that are well tolerated and that could be used as a placebo or vehicle to mask the challenge food [40]

- the quantity of food causing symptoms in order to prevent false negative food challenges

Challenges can be performed as either open food challenges (OFC), single blind placebo controlled food challenges (SBPCFC) or DBPCFC (Fig. 14.3) [40].

Open food challenges

During OFC both the clinician and patient (or parent) is informed of the food being administered and these challenges should be sufficient to either confirm or refute most reported food hypersensitivity. However, many children are very reluctant to eat a food which they do not remember having eaten before or which they have previously been told to avoid. Indeed it is not uncommon for children who have had previous severe reactions to foods to exhibit some degree of food avoidance. It is therefore often advisable to provide the challenge in a ‘single blind’ form (culprit food mixed with another food acceptable to the child) simply to ensure that the child consumes it [41, 42].

OFC are mainly used in the clinical setting and are useful for the diagnosis of objective symptoms [42]. Although factors such as starting dose, dose increment and final dose may not be that critical, it is essential that the patient has consumed an adequate amount of food during the challenge to make a diagnosis accurate [43, 44].

Single blind placebo controlled food challenges

During the SBPCFC, both active and placebo challenges are given. The health professionals involved know which food is active and which is placebo, but the patient does not. Sufficient masking of the challenge food is very important. SBPCFC are particularly useful when performing food challenges in children who do not want to ingest a specific food.

Double blind placebo controlled food challenge

The gold standard for confirming or refuting food allergy is the DBPCFC [40, 45], although in practice open challenges are more common. One of the strengths of the DBPCFC is that neither the patient nor the investigator knows when the active or the placebo challenge is performed. It therefore rules out reporting bias from the clinician and any psychological effect from the patient.

The DBPCFC is mainly used for research purposes and can be time consuming and difficult to manage. It needs to be used only in clinical practice where there is a possibility that any observed reaction could be caused by anxiety or in diagnosing subjective symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea [40, 42, 44].

Considerations when performing food challenges

Elimination period

Prior to a food challenge, the identified food should be excluded from the diet as discussed above.

Challenge dose

Guidance on performing food challenges (OFC and DBPCFC) such as the dosages given and foods used is discussed in the PRACTALL consensus guidance [45]. The PRACTALL recommendations suggest the following doses for food challenges [45]: 4.334 g of protein divided into 3 mg, 10 mg, 30 mg, 100 mg, 300 mg, 1000 mg and 3000 mg doses. In terms of amount of food given this equates to

- Milk: 12.428 g of skimmed milk powder (8.3 mg; 27.8 mg; 83.3 mg; 277.8 mg; 833.3 mg; 2777.8 mg; 8333.3 mg)

- Soya: 134.6 mL of soya milk (0.1 mL; 0.3 mL; 0.9 mL; 3.0 mL; 9.1 mL; 30.3 mL; 90.9 mL)

- Egg: 9.45 g of egg powder (6.4 mg; 21.3 mg; 63.8 mg; 212.8 mg; 638.3 mg; 2127.7 mg; 6383.0 mg); 34.711 g of egg (23.4 mg; 78.1 mg; 234.4 mg; 781.3 mg; 2343.8 mg; 7812.5 mg; 23 437.5 mg)

- Wheat: 5.5538 g of gluten powder (3.8 mg; 12.5 mg; 37.5 mg; 125 mg; 375 mg; 1250 mg; 3750 mg)

- Peanut: 8.886 g of peanut flour (6 mg; 20 mg; 60 mg; 200 mg; 600 mg; 2000 mg; 6 000 mg); 18.5126 g of peanut butter (12.5 mg; 41.7 mg; 125 mg; 416.7 mg; 1250 mg; 4166.7 mg; 12 500 mg)

This amount of food, however, should still be followed up with an age appropriate portion of the food at the end of a negative challenge [45]. The interval between doses can be anything between 15 and 60 minutes but the timing between each dose should be dependent on the patient’s history and sufficient to allow symptoms to develop.

There are currently no specific recommendations regarding the dose or design to be used when performing food challenges to diagnose delayed symptoms, e.g. atopic dermatitis or constipation, apart from that the amount normally known to cause a reaction should be used, or a normal portion of the food [44]. This raises practical issues where the patient is a very vague historian. Another difficult issue is that some reactions only occur when the causative food is eaten in sufficient doses on consecutive days and this must be planned for when designing the food challenge. The advantage of these challenges is that the reactions are not life threatening so the whole challenge can be completed at home.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree