7. Food hypersensitivity—allergy and intolerance

Isabel Skypala

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter the reader will be able to:

• Classify food hypersensitivity (FHS);

• Explain the immunological basis of food allergy (FA);

• List the main foods which can cause FHS reactions in adults;

• Describe and critically appraise the main diagnostic tests used in FHS;

• Explain when diagnostic diets and oral food challenges would be appropriate; and

• Describe the factors to be considered when advising on the management of FA.

Introduction

Definition

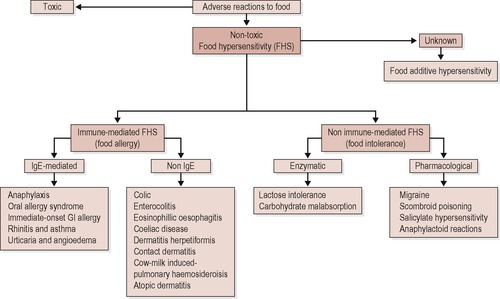

Adverse food reactions can be classified into toxic and non-toxic; 1 toxic reactions occur in any individual exposed to a sufficient dose of a substance, but non-toxic ones only occur in an individual susceptible to certain foods. Non-toxic reactions are classified as food hypersensitivity (FHS) reactions, with reactions to foods involving immunologic mechanisms defined as food allergy (FA), and divided into IgE and non-IgE mediated reactions (see Figure 7.1). 2,3

|

| Figure 7.1 • |

FHS reactions not known to involve the immune system are classified as non-allergic FHS, but may also be referred to as non-toxic, non-immunologic reactions. 3,4 These reactions include enzymatic reactions such as lactose intolerance and carbohydrate malabsorption, and pharmacological reactions related to the ingestion of foods containing vasoactive amines or salicylates. Conditions such as food-dependant, exercise-induced anaphylaxis (FDEIA) and reactions to food additives may involve the immune system, but the aetiology and pathogenic mechanisms are uncertain. 4

Epidemiology and prevalence

About 20% of the population alter their diet because they believe they react to a food or food component; however, perceived prevalence is usually much greater than actual prevalence. 5.6. and 7. The prevalence of allergic disorders is associated with age and commonly referred to as the ‘allergic march’ with food allergy and atopic dermatitis predominating in early years and asthma and allergic rhinitis peaking in teenage and adult years. 8 Most IgE-mediated FA is acquired in the first 1–2 years of life, but it is still unknown whether most FA in adults represents a persistence of childhood symptoms or is a response primarily initiated in adulthood. 9 Up to 4% of adults may have an IgE-mediated FA, with prevalence often linked to aero-allergen sensitisation. 10.11.12. and 13. The most prevalent non-IgE mediated FA is coeliac disease, common in Europe, southern Asia, the Middle East, Africa and South America and thought to affect 1% of the UK population. 14,15

The prevalence of non-immune mediated FHS is variable. Lactose intolerance affects on average 6–12% of Caucasians, but the range is very wide with 2% of Scandinavians and 70% of Sicilians being intolerant, and as many as 80–100% of Africans and Asians. 16 About 70% of people with irritable bowel disorder feel they have a problem with food and often link the consumption of milk and wheat to their symptoms. In one study, 42% of subjects perceived milk to cause their symptoms, and about 15% felt wheat in the form of bread or flour caused intolerance. 17

Physiology and pathophysiology

Mechanisms of response

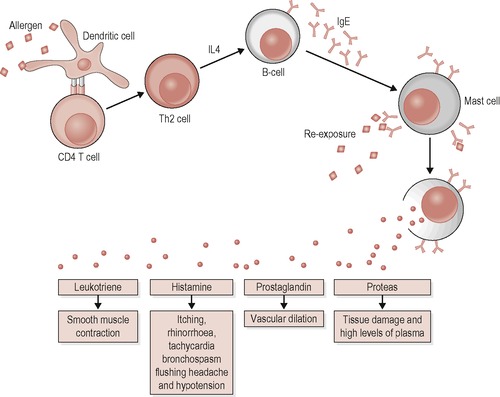

Food allergic reactions are mediated by the immune system. There are two types of immunity, innate and adaptive. The main cells involved in adaptive immunity, the T and B lymphocytes, can recognise substances produced by microbes and non-infectious molecules known as antigens. 18 Sometimes antigens from pollens, animal dander or food proteins elicit immune responses known as hypersensitivity reactions; when this happens the antigens are known as allergens. 19 B lymphocytes (B cells) produce the antibodies immunoglobulin M (IgM), IgG, IgA and IgE; IgE is the main antibody involved in food allergy. 20 T lymphocytes (T cells) can be either cytotoxic T cells or T helper (Th) cells, and it is the latter that are involved in FHS reactions. When activated by the antigen, Th cells develop into either Th1 cells or Th2 cells, depending on the type of mediator proteins (cytokines) the antigen-presenting cell (APC) is secreting. 18 When a Th2 cell is activated, it produces cytokines which make B cells produce IgE antibodies specific to the antigen presented to the T cell. 21 This antigen-specific IgE does not circulate freely but attaches itself to surfaces of mast cells and blood basophils. 22 Re-exposure enables the antigen to bind onto the specific antibody and when several IgE antibodies on the mast cell bind to the antigen, the mast cell degranulates and releases preformed mediators which cause the symptoms of food allergy (see Figure 7.2).

|

| Figure 7.2 • [Adapted from Abbas and Lichtmann 2001]. 18 |

This response is immediate hypersensitivity or type I hypersensitivity and is the response that predominates in FHS. There are three other types of hypersensitivity reactions; types II and III are not thought to be involved in food allergy, but non-IgE-mediated food allergy may involve a type IV hypersensitivity which is cell-mediated and generally involves Th1 cells. Whereas type I hypersensitivity is immediate, type IV reactions are delayed; examples of type IV hypersensitivity include contact dermatitis and food-protein-induced entercolitis. In coeliac disease, a response to allergens found in cereals promotes an inflammatory reaction which involves both innate and adaptive immunity.

For non-immune-mediated FHS, the pathogenic mechanisms underlying the reactions are diverse and often unknown. There is evidence that in IBS patients, the anti-inflammatory response in respect to cytokine production may be suboptimal and also that there are increased levels of food-specific IgG antibodies. 23 Lactose intolerance is caused by lactase activity decreasing after weaning, and this occurs in 70% of adults worldwide, mainly from non-Caucasian races. 16

Food allergens

Food allergen nomenclature is composed of the first three letters of the genus, the first letter of the species name followed by an Arabic number (http://www.allergen.org). 24 For example, the botanical name for peanut is Arachis (genus) hypogaea (species) so the allergens are labeled Ara h 1, Ara h 2, etc. Food allergens are graded as either class 1 or class 2 allergens, and one food may have both class 1 and class 2 allergens. 25 Class 1 allergens are large water-soluble glycoproteins, stable to heat, acids and proteases, which allows them to sensitise during ingestion, breaching the normal immune tolerance to foods. 5,26 Class 2 allergens are usually heat labile, difficult to isolate and susceptible to enzymatic degradation, and so cannot sensitise upon ingestion. 25

An allergen will have one or more sequences of amino acids known as epitopes, which are recognised by the antibody, thus enabling the allergen to bind with the antibody. There are two types of epitopes; sequential (linear) epitopes are composed of single segments of sequential amino acids along the polypeptide chain. Conformational epitopes are composed of amino acids from different parts of the protein sequence, brought together by folding. Conformational epitopes can be destroyed when the protein is altered due to heating or proteolysis, whereas sequential epitopes are not affected. Epitopes on different allergens can have a degree of amino acid sequence similarity, known as homology, which enables an antibody specific to one allergen to bind with another structurally similar allergen epitope. Homologous epitopes are common in food allergy, and account for the cross-reactivity between different foods and also between foods and pollens.

A wide range of foods and food additives are implicated in the spectrum of FHS; however, cow milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, soy, wheat, peanuts, tree nuts and seeds account for 90% of IgE-mediated food reactions. 27 Adults are most likely to have IgE-mediated allergy to fruits, fish, shellfish, peanuts and tree nuts. 5

Diagnosis

Clinical history

One of the most important steps in the diagnostic process is establishing a good clinical history. 4 The history should uncover facts about the likely foods causing the reaction, quantity associated with a reaction, speed of onset of symptoms, duration of symptoms and other factors such as whether the reaction is concurrent with exercise, medications or alcohol. 5 The history can help determine whether the FHS is likely to be immune-mediated and therefore likely to involve specific IgE antibodies. IgE-mediated reactions are usually immediate, and involve allergic symptoms such as pruritis (itching), which may be accompanied by flushing, angiooedema (swelling) and hives or urticaria. These symptoms may be localised or systemic and accompanied by a fall in blood pressure, tachycardia and bronchospasm. A reaction characterised by severe systemic symptoms is known as anaphylaxis and can be fatal. Other symptoms accompanying the reaction or appearing later on are nasal symptoms such as rhinorrhoea, sneeze, blockage or sinus involvement, and respiratory symptoms such as wheeze, cough and reduced lung capacity.

The symptoms of non-IgE-mediated FA may include atopic dermatitis (eczema) or non-specific GI symptoms which may appear some hours after the food has been eaten. Non-immune-mediated FHS reactions also can be delayed, although for some triggers such as histamine- or sulphite-containing foods, the symptoms can occur within 30 minutes of ingestion. The difference between FA and non-immune-mediated FHS is that the latter is often not obviously connected to just one food.

Poor dietary recall or concern about nutritional adequacy can be remedied by asking the patient to complete a diet diary. However, the clinical history can be inaccurate due to cross-reactions, or because the food has been contaminated or infested with parasites due to which the allergy is occurring. In most cases, the history should therefore be confirmed or refuted through the undertaking of different tests.

Diagnostic tests

Skin prick testing

Providing the subject has been avoiding antihistamines for 48 hours, skin prick testing (SPT) is a fast and relatively accurate way to confirm clinical history if an IgE-mediated FA is suspected. 5,28,29 A drop of allergen solution is placed on the forearm and pricked through with a sterile lancet using a separate one for each drop. 30 Positive (histamine) and negative (diluent) controls are used to evaluate the reactivity of SPT, with a positive test usually being one where the wheal diameter is ≥ 3 mm the negative control (see Figure 7.3). 4,30.31. and 32.

|

| Figure 7.3 • |

A positive test is not conclusive evidence of a food allergy; many people can be sensitised to an allergen without experiencing clinical symptoms. The positive predictive value (PPV) of SPT is only 50–60%, compared to a negative predictive value (NPV) of 95%. 25,33,34 This poor PPV underlines the importance of only testing those foods to which symptoms are reported rather than using a standard panel for screening. 4,9 However, even a 95% NPV still requires interpretation within the context of the clinical history. A negative test may be due to the destruction of heat-labile allergens during manufacture or variability of allergen extracts, so some advocate the use of fresh foods for testing. 35.36. and 37. When using fresh foods, the prick-by-prick method (PPT) is normally used; solid food is pricked and then the same lancet is used to prick the forearm, or a drop of liquid food is placed on the skin and the skin pricked through this. This form of testing is superior when investigating allergy to fruits and vegetables due to the many class 2 allergens present. 34

The size of the SPT wheal does not correlate with severity of reported symptoms, but can help to predict the likelihood of reaction if challenged with that food. Several studies have provided predictive values for SPT wheal diameters, but none of these are for adults and the variability of the results makes it difficult to extrapolate the findings to other geographical population groups (see Table 7.1). 34,38.39.40. and 41.

| Food | PPV% | SPT (mm) | Reference: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | 5 | Eigenmann and Sampson 199834 | |

| 100 | ≥ 8 | Hill et al 200438 | |

| ≥ 8 | Sporik et al 200039 | ||

| 95 | 12.5 | Verstege et al 200540 | |

| 99 | 17.3 | Verstege et al 200540 | |

| Egg | 4 | Eigenmann and Sampson 199834 | |

| 100 | ≥ 7 | Hill et al 200438 | |

| ≥ 7 | Sporik et al 200039 | ||

| 95 | 13.0 | Verstege et al 200540 | |

| 99 | 17.8 | Verstege et al 200540 | |

| Peanut | 6 | Eigenmann and Sampson 199834 | |

| 100 | ≥ 8 | Hill et al 200438 | |

| ≥ 8 | Sporik et al 200039 | ||

| 100 | ≥ 16 | Rancé et al. 200241 |

Serum-specific IgE (sIgE) antibody estimation

The measurement of sIgE antibodies is a useful alternative to SPT, when SPT are not available, or when patient has taken antihistamines, has dermographism (sensitive skin which responds by producing a wheal to a pen mark on the skin) or a severe skin condition such as eczema, or is at risk of a severe response. Guidelines suggest that SPT and sIgE estimation are interchangeable; either can be used to good effect with clinical history, but both may be required if there is a discord between the clinical history and the test result. 31 A variety of different manufacturers provide sIgE tests using different substrates and reporting results differently; some use a system of classes from 0 to 6 and others report in kilo units of allergen/litre (kU A/L) or as ‘graded’ levels (grade 1–6) where

Grade 0 = < 0.35 kU A/L

Grade 1 = 0.37–0.7 kU A/L

Grade 2 = 0.7–3.5 kU A/L

Grade 3 = 3.5–17.5 kU A/L

Grade 4 = 17.5–50 kU A/L

Grade 5 = 50–100 kU A/L

Grade 6 = > 100 kU A/L

Generally, level 2 and above is considered as positive in clinical practice, although this is not evidence-based and those patients who have very low levels of positivity to foods should have a SPT to confirm the result. Specific IgE has a similar negative predictive value to SPT but undetectable serum food-specific IgE levels might occur in 10–25% of clinical reactions depending on the food involved. 28 Research has also been carried out to try to quantify the amount of sIgE predictive of a positive challenge for different foods. Published predictive values are summarised in Table 7.2, but again this work has only been carried out in children. 41.42.43.44.45. and 46.

| Food | PPV% | Specific IgE (kU/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | 95 | 32 | Sampson 199742 |

| 95 | 15 | Sampson 200143 | |

| 95 | 5 | Garcia-Ara et al. 200144 | |

| Egg | 95 | 6 | Sampson 199742 |

| 95 | 7 | Sampson 200143 | |

| 95 | 13 | Celik-Bilgili 200545 | |

| Fish | 100 | 20 | Sampson 200143 |

| Peanut | 95 | 15 | Sampson 199742 |

| 95 | 14 | Sampson 200143 | |

| 100 | 57 | Rancé et al. 2002 41 | |

| Tree nut | 95 | 15 | Clark 200346 |

| Soy | 73 | 30 | Sampson 200143 |

| Wheat | 74 | 26 | Sampson 200143 |

Atopy patch test (APT)

This test is principally recommended for use in the diagnosis of delayed non-IgE-mediated FA such as atopic dermatitis, identifying cell-mediated reactions to foods. 31 APT needs an experienced evaluator and does not substantially affect the number of oral food challenges required for diagnosis. 29,47

Serum food-specific IgG

IgG antibodies to foods are found commonly in healthy adults, independently of the presence or absence of food-related symptoms, and reflect the level of food exposure. 29,48 A high total IgE can also stimulate production of IgG antibodies. 4,49 It has been proposed that there is evidence of low grade inflammation in people with IBS that may impair the ability to mount an adequate immune response and two studies have suggested that the measurement of food IgG antibodies might be a useful way of identifying foods which could improve the symptoms of IBS if eliminated from the diet. 23,50,51 However, the role of IgG or its subclasses has not yet been substantiated in the diagnosis of clinical allergy. 4,52

Coeliac disease

A first-line test for coeliac disease will usually be the use of serological antibody tests, which evaluate levels of the IgA class of anti-tissue transglutaminase (TTG) and/or endomysial antibody (EMA). 53 They have a sensitivity and specificity of > 90%, although test accuracy depends on there being no damage to the small intestine and normal levels of IgA antibody in the blood. 54,55 Patients with low or negative total IgA will need to have the IgG class of TTG/EMA evaluated instead. 56 It is recommended that a positive test be confirmed with a small bowel biopsy, the gold standard of diagnosis, which requires the consumption of a gluten-containing diet for at least 6 weeks prior to the test. 57.58. and 59.

Lactose intolerance

The lactose tolerance test requires a fasting blood sample, followed by an oral dose of lactose and further sequential blood samples to determine the level of lactose. 16 Another test is the breath hydrogen test; a fairly reliable method for the diagnosis of lactose malabsorption where the amount of hydrogen in the exhaled breath correlates with the amount of malabsorbed lactose. 60 Undigested lactose is fermented in the lower bowel and creates lactic acid, so lactose intolerance can also be diagnosed by checking the stool pH, or looking for faecal-reducing substances. 16

Non-validated tests

There are a variety of other tests including the leukocyte cytotoxic test, hair analysis, bio resonance diagnostics, auto homologous immune therapy, kinesiology, iridology, sublingual provocative food testing, homeopathic remedies and electrodermal testing including electroacupuncture and Vega testing. However, few have been scientifically investigated and none validated for the accurate diagnosis of FHS. 61

Diagnostic diets

An important clue to the role of a food causing problems can be derived from the resolution of symptoms upon removal of that food. 62 Diagnostic diets involve the supervised exclusion of a suspected food, followed by its reintroduction in the form of an oral food challenge. All patients should keep a symptom diary, to record symptoms related to the exclusion and subsequent reintroduction of foods, and also to check that foods are actually being reintroduced in a systematic way. Where there is strongly positive specific IgE to a known food trigger which elicits immediate symptoms, there is no requirement for a diagnostic diet; the patient should be advised to avoid that food. 63 Where there is discordance between the specific IgE tests and the clinical history, a 4- to 6-week avoidance of a food or food group may be helpful; if symptoms improve, then an oral food challenge should be carried out. 64 Patients waiting for a diagnosis are often already avoiding suspect food(s); however, their dietary intake should be checked as they may be ingesting small amounts of the suspect food allergen without realising.

Where there is no obvious food trigger, or non-IgE-mediated FA or non-immune-mediated FHS is suspected, then a multiple exclusion diet or oligoantigenic might be useful. 64 Such diets normally exclude foods most frequently implicated in allergic responses such as milk, grains, eggs and often citrus fruits, nuts, coffee and chocolate. 27 This diet is followed for 2–3 weeks and then foods are reintroduced singly and gradually at intervals of a few days. However, for those who report severe symptoms, or where psychological factors including food aversion may be involved, the reintroduction of food should be viewed as a food challenge and carried out under controlled conditions. A total exclusion diet is used when other avenues fail, or when extreme self-imposed restrictions need to be assessed. The diet usually consists of one meat (e.g. turkey, rabbit or lamb), two to three vegetables such as carrots, broccoli or cauliflower, two fruits (excluding citrus fruits), and two starchy foods such as rice, sago, tapioca or buckwheat. 65 The diet should be followed for a maximum of three weeks, and key foods reintroduced singly, two or three per week.

Food challenge

The aim of the oral food challenge (OFC) is to confirm or refute the involvement of a food, food additive or food component in triggering the individual’s clinical symptoms. 66 Only 30-50% reported reactions to food are confirmed by an OFC, and since food allergy has a significant impact on the quality of life for the sufferer, challenges are essential in order to avoid unnecessary food restriction or misdiagnosis. 27,67,68 European Guidelines suggest that OFC should be used for everyone with a history of adverse foods reactions in order to establish or exclude a diagnosis of FHS. 69 The two main types of OFC are the open challenge (OC), where the food is not disguised, and the double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), where the food is disguised so that neither the subject nor the person administering the challenge is blinded as to the challenge dose. 27

An OC is most suitable for immediate-onset IgE-mediated food allergy with objective symptoms that can be seen and recorded independently, or when a negative outcome is expected. For standard clinical practice, the OC is the most practical option and guidance suggests it can precede DBPCFC; a negative result negating the need for DBPCFC. 69 Some protocols commence with a labial challenge; the suspect food is rubbed on the outer lip and then exposed to the oral mucosa without being swallowed. For some types of allergy to fruits and vegetables, good contact with the oral mucosa is vital and a portion of the food may be sucked/chewed and disgorged as a starting dose prior to ingestion. 37,70 The starting dose of the suspect food should be half that reported to cause a reaction, with subsequent doses increased incrementally (usually double the preceding dose) (see Figure 7.4) given every 15 minutes, depending on the reported speed of onset of symptoms. 64 The total amount of the suspect food given during the whole challenge should equal 8–10 g of dry food or 100 ml liquid or 200 g solid ‘wet’ food. 64 European guidelines recommend that the final dose should equate to a standard portion of that food. 69

|

| Figure 7.4 • |

For DBPCFC, the suspected food is hidden inside a carrier such as a biscuit, custard, fruit puree or even a hamburger. Coffee powder, cocoa powder or peppermint syrup can be used to disguise the taste of foods, and blackcurrants can disguise both taste and colour. Peel and pips may need to be removed from fruits although this does remove some of the allergen, making blinded challenges with fruits and vegetables difficult. It is recommended that fresh rather than dried food should be used, unless the dried food has been specially formulated for use in DBPCFC and its allergenicity tested prior to use. 71,72 DBPCFC are best performed using two placebo and one active challenges, randomised and given sequentially, with each challenge being given as a titrated dose as with the open challenges. Best practice recommends these challenges be given on 3 separate days but if not possible then the patient needs to be symptom free before the next challenge may commence. 73,74 Challenges for delayed reactions will need also to be given over several days, but it may be possible to complete these at home, depending on the severity of symptoms. Augmentation factors also need to be considered, such as exercise, 75 aspirin, infection, hormonal and multiple food combinations as these may all affect the final outcome of challenge. 4,66

The difficulties experienced when undertaking challenges lead some to suggest they may not be necessary for most patients. 66,76 Predictive values for SPT and sIgE, together with better allergen reagents, may reduce the number of challenges needed, but some IgE-mediated hypersensitivity responses are so localised that they are undetected by IgE testing and can only be confirmed by food challenge. 77

Management

Allergen avoidance

The main management of any FHS will be to avoid known food triggers; this is greatly facilitated by EU labelling regulations, 78 which require specified allergens to be declared on prepackaged foods if they have been added deliberately, however small the amount. The foods covered include cereals containing gluten, crustaceans, eggs, fish, peanuts, soybeans, milk, nuts, celery, mustard, sesame seed and sulphur dioxide and sulphites at more than 10 mg/L/kg. The directive was updated in 2007 to include lupin and molluscs. 79

Thus dietary exclusion can be straightforward although it is important to review the patient’s current diet to assess inadvertent consumption of allergens. It is also important to give advice which will minimise accidental allergen exposure, such as occurring through inhalation of aerosolised allergens, transfer of allergens during cooking, touch and absorption through the skin, traces in foods and even kissing. 4 The Food Standards Agency has issued guidance for industry on risk assessment, although there is as yet no legislation for unwrapped foods or foods consumed in restaurants, 80 which is unfortunate since many reactions occur when eating out of the home. 81

Food avoidance can affect quality of life, 68 and social life is improved after the reintroduction of foods following a negative challenge. 82 Children, teenagers and adults with FA experience problems associated with their FA irrespective of age. 83 Adolescents and young adults with food allergy may indulge in risk-taking behaviour, knowingly and purposefully ingesting potentially unsafe foods. 84 It is important to discuss any concerns and anxieties the patients have to help them live with a high degree of confidence and a feeling of being in control of their life. 85

Specific foods

Milk and egg allergy

Milk and eggs are the most common causes of allergy of FA in children worldwide but this often resolves in childhood. Teenagers and adults on milk- or egg-free diets since childhood should be assessed for resolution of the allergy. Even where egg allergy has not resolved, it may be possible to allow the diet to be more relaxed since over 70% of those with a persistent egg allergy may tolerate cooked egg. 86 Both cow’s milk and hen’s egg are highly cross-reactive to milk and eggs from other animals, and all such relevant associated foods should also be avoided. Milk or egg allergies are rarely diagnosed in adulthood although egg allergy can occur in adults with allergy to bird feathers, through a cross-reacting allergen in the egg yolk.

Lactose intolerance is probably the most well-characterised non-immune-mediated hypersensitivity reaction to milk. Not all milk products contain lactose; hard cheeses such as cheddar and stilton have negligible lactose content, although soft cheeses such as cream cheese will need to be avoided. Some people with lactose intolerance can tolerate yoghurt. There are commercial enzyme preparations, which can be added to foods to enable them to be digested; also, milk treated with such enzymes can often be purchased in supermarkets, especially in areas with a large non-Caucasian population.

Over 40% of food-related symptoms in IBS are thought by sufferers to be caused by milk. Milk consumption has also been linked with respiratory conditions, and an increased mucous or phlegm production. Milk avoidance is therefore common in those with IBS and asthma and this can have a deleterious effect on nutritional status. For women, especially if they are taking regular corticosteroids, an optimal calcium intake is important to safeguard bone density. A milk substitute should be recommended and if one is already being taken, it needs to be checked in order to ascertain whether it is fortified. A dietary assessment is essential to ascertain whether supplements are required. For those with an egg allergy, nutritional issues are less common but it is important to review awareness of loosely cooked egg dishes such as meringue, omelettes and egg custards which can be tolerated by some egg allergic individuals but not all.

Seafood

Fish and shellfish are common causes of FA; one study suggests shellfish is the most common cause of anaphylaxis in Americans over the age of 6 years. 87 Fish and shellfish do not usually cause non-IgE-mediated FA, but a reaction due to increased levels of histamine in certain fish may occur. This is known as scombroid poisoning and may be confused with fish allergy due to the typical symptoms of flushing, sweating, urticaria, GI symptoms, palpitations and occasional bronchospasm. 88 Allergy to seafood does not usually resolve, although there have been case reports suggesting this may occur occasionally. 89

There is strong cross-reactivity between fresh and saltwater fish, although a fish-allergic individual may not always have clinical symptoms to other cross-reacting fish. 90 The cod is the most allergenic fish, together with salmon and herring; there is strong cross-reactivity between cod, mackerel, herring and plaice; 90 also between salmon, trout and tuna; and mackerel and anchovy. 91 Crustaceans share a common allergenic protein called invertebrate tropomyosin. The main shrimp allergen Pen a 1 is similar to other allergens both in other crustaceans, such as crab, lobster and crayfish, and in molluscs, house dust mite and cockroaches. 92 There is no cross-reactivity reported between crustaceans and finned fish. 4,92

Seafood-specific IgE tests are very reliable and so a positive test, together with a convincing history, is usually sufficient to make a diagnosis. However, due to the often very severe reported symptoms, and the possibility of a differential diagnosis, a negative specific IgE screen needs confirmation by OFC. Unless other species are tried through oral challenge, it is probably safer to advise avoidance of all fish due to cross-reactivity. Fish allergens are heat labile and so there are people who will be able to consume canned salmon or tuna but not raw, smoked or lightly cooked fish. 93 For crustacean allergy, all crustaceans and molluscs should be avoided due to unknown cross-reactivity. Also shrimp allergens are very robust and may be found in oil used to cook prawns and so contamination can be a major problem, especially when eating out. 94

Avoidance of seafood does not normally cause any major nutritional problems, although those who are taking omega 3 fatty acid supplements in the form of fish oil will need to find an alternative source such as linseed (flax seed) or algae oil (Food Standards Agency website).

Plant foods (peanuts, tree nuts, seeds, fruits and vegetables)

Allergy to nuts, fruits and vegetables are very significant in the adult population. Many plant foods from unrelated botanical families have homologous allergens leading to extensive cross-reactivity between plant foods from different botanical families, and between plant foods and pollens. The plant food allergens are classified by their different allergen types, rather than botanical families and one food may have allergens in several different families. 95,96

Peanuts

Peanut allergy usually presents in early childhood, 97 but unlike milk and egg allergy, only 20% of cases will resolve, with 8% of these cases likely to have a reoccurrence. 98.99. and 100. Most peanut allergy in adults will be unresolved childhood allergy; for those with newly diagnosed with peanut allergy, it unknown whether this is a primary sensitisation to peanuts or cross-reactivity reaction to other foods or aero allergens.

Many of the peanut allergens are resistant to heat and proteolysis and hard to eradicate. For example, it is known that one of the peanut allergens, Ara h 1, can remain in the saliva for up to an hour after eating, 101 requires detergent or soap to be removed from surfaces, 102 and increases in allergenicity if roasted rather than being boiled or fried. 103 Most people are sensitised to Ara h 2, 104 but only those with severe symptoms are co-sensitised to Ara h 1. 105 Not all peanut allergens are so robust; Ara h 5 and Ara h 8 may be fully or partially destroyed on heating. 106,107

A good clinical history and matching positive SPT or specific IgE is sufficient to make a diagnosis of peanut allergy. However, if SPT or blood tests are negative, it is very important to confirm or refute the diagnosis by undertaking OFC as a diagnosis of peanut allergy can severely restrict the diet, mainly due to the level of nut trace warnings on foods. Most people with a peanut allergy will be advised to avoid all tree nuts in addition to peanuts, partly because they are at increased risk of having reactions to tree nuts, but also because of the issue of contamination. There are no major nutritional risks for those on peanut-free diets, unless they are also avoiding other major food groups or are vegetarian or vegan.

Other legumes

People with a peanut allergy are often co-sensitised to other legumes but this rarely manifests itself as a clinical issue. 108 Soy, chickpea and lentil allergy are mostly seen in children, and although legume allergy can occur in adults the incidence is unknown. 109 However, severe reactions to lupin, a legume added to bread and flour in Europe in the form of lupin flour, have been reported. French pastry, apple flan, battered onion rings and gluten-free pasta have all been involved in reported reactions. Lupin allergy can occur independently of peanut allergy and can be very severe, 110 hence its inclusion in the EU food allergen labelling scheme in 2007.

Tree nut allergy

There is cross-reactivity between tree nuts and peanuts; up to half of those allergic to peanuts could also be allergic to tree nuts. 111.112. and 113. About 0.5–1% of people are likely to develop a tree nut allergy, with resolution in about 9% of cases. 114 In the UK, the commonest tree nuts involved are Brazil nut, hazelnut, walnut and almond, although cashew nut allergy is increasingly prevalent, often causing severe reactions on first exposure. 115,116 Most tree nut allergy is thought to develop in childhood; in adults it may be a primary allergy but more often is associated with cross-reactivity to tree pollen. Although tree nut allergy is usually diagnosed through the combination of a good clinical history and specific IgE evaluation, some test reagents do not give good results for nuts, and so a convincing history and negative tests should be followed up with PPT using fresh nuts, followed by OFC.

Seeds

Sesame and mustard seed are the two seeds most commonly involved in FA. The major allergens in sesame are oleosins, found in the oil fraction of the seed, 117 so whole seeds may not cause reactions whereas a sesame oil might. Mustard seed has been reported to cause severe reactions and is a common allergen in France. 118 SPT and specific IgE estimations are not always reliable, so a careful history is essential. Allergy to sesame and/or mustard should be excluded in people presenting with reported reactions to a variety of seemingly unconnected foods.

Fruit and vegetables

Allergy to fruits and vegetables is probably the most common form of FA in adults, affecting an estimated 5% of the population. 5 Although symptoms can be mild, severe reactions are not uncommon; fruit was cited as causing 12% of all anaphylaxis reactions in North America. 87

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree