Historically, practice guidelines and various medical resources have combined follicular thyroid cancer (FTC) with papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) as if they were a single entity of “well-differentiated thyroid cancer.” Although they are derived from the same cell of origin, they are each driven by distinct genetic alterations which result in unique clinical characteristics. There are important differences in the diagnostic workup, cancer management, and prognosis between FTC and PTC. Future guidelines and studies should separate them as distinct clinical entities.

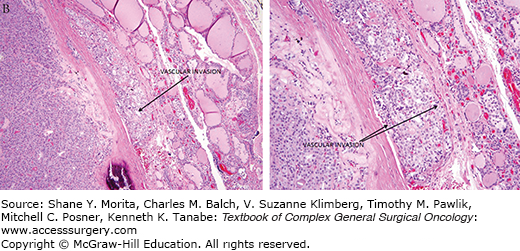

FTC can be stratified into low-risk, minimally invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma (MIFTC) and high-risk, widely invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma (WIFTC).1 MIFTC is characterized histologically by microscopic penetration of the tumor capsule without vascular invasion, and behaves similarly to benign follicular adenomas. Disease recurrence is extremely rare after complete surgical resection of MIFTC. In contrast, WIFTC is associated with a substantial risk of both local recurrence and hematogenous metastases. Controversies in the optimal management of FTC exist due to the lack of randomized controlled studies. Treatment of FTC should be based on individual risk assessment.

The overall incidence of thyroid cancer has increased in recent decades. This is a result of both increased detection and a true increase in disease incidence. FTC is the second most common subtype of thyroid carcinoma following PTC, and comprises approximately 10% of all thyroid cancers. FTC is more common in women than in men, with an approximate 3 to 1 ratio, although this varies depending on region. In Japan, the female to male ratio of FTC is as high as 13 to 1. FTC has a peak age of onset between 40 and 60 years old. In comparison, PTC has a peak age of onset between 30 and 50 years old.

Environmental factors may play a role in FTC development. FTC is more common in regions of iodine deficiency. Childhood exposure to ionizing radiation, whether therapeutic or environmental, is associated with an increased risk of both FTC and PTC. Lastly, both FTC and PTC are linked to genetic mutations.

Although specific genetic alterations have been observed in FTC, the genetic basis of oncogenesis remains poorly understood. RAS mutations are found in 40% to 50% of FTC, however up to a third of follicular adenomas also have RAS mutations. There is some evidence suggesting that follicular adenomas harboring RAS mutations may actually be precursors of FTC.2

In addition to RAS mutations, the PAX8/PPARϒ chromosomal rearrangement can be found in up to 30% of patients with FTC. Similar to RAS, the PAX8/PPARϒ rearrangement is not specific for FTC, as it is also found in a small percentage of follicular adenomas. RAS mutations and the PAX8/PPARϒ rearrangement are non-overlapping in FTC. RAS mutations or the PAX8/PPARϒ rearrangement are found in up to 70% of FTCs.

Several groups have established genetically engineered mouse models of FTC. The thyroid-specific deletion of the Prkar1a gene in mice causes invasive FTC without distant metastases, likely through the upregulation of PKA. Older mice with thyroid-specific Pten loss are also prone to the development of FTC in addition to follicular adenomas. Interestingly, the combined knockout of Prkar1a and Pten causes FTC with hematogenous metastases to the lung. Although Prkar1a and Pten mutations are rarely seen in human FTC, the activated signaling pathways, histologic features, and pattern of metastases in this model closely resemble advanced human FTC.3

Upon gross inspection, FTCs are often gray-tan encapsulated lesions. They can be focally hemorrhagic, fibrotic, or demonstrate areas of calcification. Rarely, FTCs have gross evidence of local invasion.

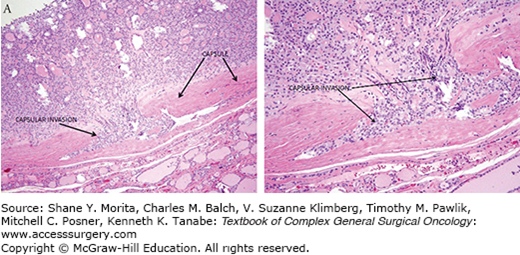

Under microscopic examination, most FTCs are composed of cells with nuclei that are round to oval with uniformly speckled chromatin. FTCs do not demonstrate the nuclear features characteristic of PTC. FTCs can have a follicular or solid architectural pattern. FTCs demonstrate capsular and/or vascular invasion (Fig. 35-1). Lymphatic invasion is rare. The Hűrthle cell variant of FTC is discussed in a separate chapter.4

FTCs are often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on self-palpation, routine physical exam, or imaging studies. FTCs are typically small without compressive symptoms or thyroid dysfunction. Rarely, FTC can present with symptoms from tumor mass effect, local invasion, or distant metastases. Such symptoms can include voice changes from recurrent nerve dysfunction, neck fullness, or dysphagia. Rarely, distant metastases are the initial finding in the diagnosis of FTC.

Accurate staging of FTC is important in determining the prognosis and optimal treatment. The most widely used staging system for FTC is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Classification System for Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma, as referenced in the 2009 Revised American Thyroid Association Thyroid Cancer Guidelines (Table 35-1). The TNM Classification System is described below.5,6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree