CUP subset

Diagnosticsa

Pathology

Treatment options

Solitary metastatic disease

Positron emission tomography (PET)

Variable

Surgery followed by

radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy

adjuvant chemotherapy

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy + surgery

Definitive radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy

Osteoblastic metastases in men with elevated serum PSA (prostate-specific antigen)

Serum PSA

Immunostains: PSA, p63, P501S, prostate-specific acid phosphatase (PSAP), prostein, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), Androgen receptor (AR)

Per guidelines for advanced/metastatic prostate cancer

Androgen deprivation therapy or

chemotherapy

Adenocarcinoma with isolated axillary lymphadenopathy in women

Mammography

Breast ultrasound

Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Immunostains: mammaglobin, GCDFP-15, GATA-3, ER, PR, HER2/neu

Per guidelines for TX or T0/N + (node-positive) breast cancer

Ipsilateral mastectomy/breast-conserving surgery with axillary lymph node dissection

Radiotherapy

Adjuvant/neoadjuvant chemotherapy ± hormonal therapy

Papillary carcinoma of the peritoneal cavity in women

Serum CA 125

Immunostains: CK7, P53, WT-1, ER, PAX-8, Ber-EP4, MOC-31

Per guidelines for stage III/IV epithelial ovarian cancer

Chemotherapy (platinum/taxane) only for distant metastases excluding peritoneal disease

Cytoreductive surgery + chemotherapy (platinum/taxane)

Poorly differentiated carcinoma with midline distribution

Testicular ultrasound

Serum AFP and βHCG

Immunostains: AFP, βHCG, OCT-4

Per guidelines for poor-risk germ cell tumors

Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy

Squamous cell carcinoma with cervical lymphadenopathy

CT head/neck + PET/CT

Laryngoscopy with directed biopsies

Bilateral tonsillectomy

No specific immunohistochemistry

Per guidelines for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

Lymph node dissection

Radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy

Adenocarcinoma with immunophenotype consistent with gastrointestinal primary

Colonoscopy (if clinically indicated)

Immunoprofile: CDX2 positive, CK20 positive, CK7 variable

Chemotherapy

FOLFOX or FOLFIRI

Targeted agents (bevacizumab, cetuximab/panitumumab in RAS wild-type tumors)

Neuroendocrine cancer of unknown primary

Well differentiated:

Octreoscan

Urinary 5-HIAA

Poorly differentiated:

PET

Brain MRI

Immunostains: Synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD56, Ki-67

Per guidelines for neuroendocrine tumors

Well differentiated:

Local therapy (surgery, embolization)

Systemic therapy (somatostatin analog, cytotoxic, sunitinib, everolimus)

Poorly differentiated:

Chemotherapy (cisplatin/carboplatin + etoposide or irinotecan)

10.2 Solitary Metastatic Disease

Case Study

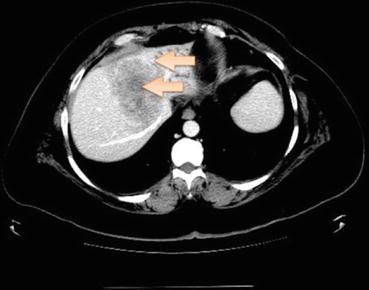

A 72-year-old lady presented with pneumonia. Chest X-ray (Fig. 10.1a) showed a right lung mass. CT-guided biopsy showed moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. Immunohistochemistry was strongly and diffusely positive for CDX2, cytokeratin (CK) 20, villin, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and negative for CK7 and TTF-1. CT chest showed a right upper lobe mass (Fig. 10.1b). PET showed an intensely FDG-avid lung mass but no evidence of distant metastases (Fig. 10.1c, d). Colonoscopy and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy were performed and were normal. The patient received four cycles of mFOLFOX6 chemotherapy in neoadjuvant setting and had a partial response (Fig. 10.1e). The patient then underwent en bloc right upper lobe lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection. Pathology showed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with 11 lymph nodes without any evidence of malignancy. The patient was then followed closely with surveillance scans, and PET-CT 4-year status postsurgery showed no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease (Fig. 10.1f).

Fig. 10.1

Chest X-Ray (a), CT Chest (b) and PET Scan (c and d) showing a solitary intensely FDGavid right lung mass. CT Chest after 4 cycles of chemotherapy (e) showing partial response. Surveillance PET Scan (f) 4 years after surgery showed no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease

In several studies involving CUP patients, the number of metastatic sites has been identified as a significant prognostic factor [11, 12]. A small proportion of CUP patients present with isolated or oligometastatic disease. Aggressive management with a combination of systemic chemotherapy and radical local therapy using surgical resection and/or radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy is a reasonable option in such patients, and long-term survival in these patients has been reported [13].

Patients should be carefully selected to undergo aggressive and definite management. Exhaustive imaging should be performed to rule out any other sites of distant metastases, and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging can be useful in this regard. In a retrospective analysis of 42 CUP patients with localized disease examined by PET with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose, disseminated disease was detected only by PET in 16 (38 %) patients [14].

Multidisciplinary management of these patients can be facilitated by early engagement of surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists. Since the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in such patients is unclear, neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy can be attempted to help with chemical cytoreduction. Furthermore, a short period of neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy can also aid in selecting patients for a more radical local approach, since in most patients, other metastatic sites may become evident within this time. With localized disease not amenable to surgery, definitive radiation or chemoradiation can offer palliative benefit and a prolonged disease-free interval.

With isolated cutaneous adenocarcinoma, the possibility of an unusual primary site such as an apocrine neoplasm should be considered. These rare indolent tumors can be managed with a wide local excision and are associated with a median survival of over 4 years [15]. These tumors cannot always be distinguished from metastatic breast carcinoma using immunohistochemistry, and this distinction is made on the basis of clinical presentation and careful pathological review [16, 17].

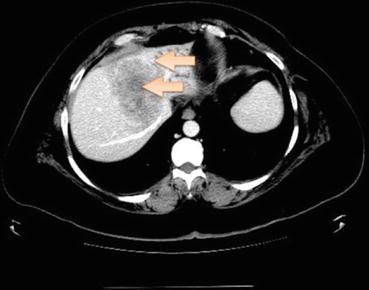

With isolated liver lesions, cholangiocarcinoma must always be considered in the differential diagnosis. Cholangiocarcinomas present as peripherally enhanced hypodense lesions and can be associated with biliary ductal dilatation (Fig. 10.2; Ref. [18]). The pathology is nonspecific though a majority of these are adenocarcinomas and express CK7. The management depends largely on the resectability of the tumor and presence of distant metastases.

Fig. 10.2

Multiphasic contrast-enhanced CT showing hypodense mass lesion (arrows) in the liver with peripheral (rim) enhancement (arrows) suggestive of cholangiocarcinoma

Within this subset presenting with solitary metastatic disease, it should be recognized that patients with soft tissue and nodal sites fare better than visceral solitary metastatic presentations, especially those with brain and liver metastases.

Summary

Select patients with CUP who present with a solitary site of disease represent a unique favorable subset that benefit substantially from aggressive therapy involving systemic chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery and can attain prolonged disease-free intervals with multidisciplinary care. Comprehensive pathological evaluation can help with neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy planning, and given the unknown biology of CUP, a detailed discussion with the patients regarding the rationale for this approach is necessary.

10.3 Osteoblastic Metastases with Elevated Prostate-Specific Antigen in Men

Osteoblastic lesions are predominantly seen in metastases from prostate, breast, and lung cancer. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a glycoprotein which is expressed in both normal and neoplastic prostate tissues and is a highly sensitive marker of prostate cancer. All patients with known prostate cancer and bone metastases have elevation of serum PSA [19, 20]. Conversely, serum PSA also has a high negative predictive value of 99.7 % for bony metastatic disease [19]. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) recommends routine use of immunohistochemistry with PSA, and positive staining is considered diagnostic for prostate cancer [21].

Men presenting with blastic bone metastases should have serum PSA evaluation and immunophenotyping performed on the pathology specimen with prostate markers such as PSA and prostein [22]. In fact, the utility of all common serum tumor markers such as CEA, CA 19-9, and CA-125 with the exception of PSA is limited in the diagnostic workup of CUP [3]. CT pelvis should be reviewed with special attention toward prostate enlargement. Multiple core biopsies using transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guidance can be performed although a negative biopsy does not rule out the prostate cancer subset of CUP.

Men with osteoblastic lesions, elevated serum PSA, and pathology suggestive of prostate cancer should be treated as metastatic prostate cancer with androgen deprivation therapy and subsequently systemic chemotherapy for castration-resistant disease [9, 23, 24].

Summary

Men presenting with adenocarcinoma of unknown primary with predominant osteoblastic metastases, elevated serum PSA, and immunophenotypic expression of prostate-specific tumor markers should be considered a favorable subset of CUP given the ease of management with initial hormonal therapy and expected benefit with treatment. Treatment guidelines for advanced prostate cancer are followed for the course of the disease.

10.4 Adenocarcinoma with Isolated Axillary Lymph Node Involvement in Women

Although the incidence of occult breast cancer is less than 0.5 %, breast cancer is the most common cause of malignant axillary lymphadenopathy in women [25–27]. Therefore, the probability of occult breast cancer should be considered high in the differential diagnosis in women presenting with CUP and isolated axillary lymph node(s) involvement. Patients with such a presentation should be managed on the lines of breast cancer and undergo a complete physical examination, mammography, ultrasound, and if these are negative, MRI of the breasts to look for any indication of a breast primary.

The immunophenotype of this subset is typically CK7 positive and CK20 negative. Breast cancer-specific markers include mammaglobin, GCDFP15, and GATA3 [28]. The sensitivity of these markers in breast cancer is 26 %, 14 %, and 86 %, respectively [29]. However, the expression frequency of any of these markers is variable and depends on morphology and grade of breast cancer, making interpretation of negative markers difficult [30]. Although staining for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2/neu supports a diagnosis of occult breast cancer and can be used to tailor therapy, they have low sensitivity and specificity to be used for diagnostic purposes. Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed in addition to mammography and breast ultrasound due to its enhanced sensitivity. In patients with clinically occult breast cancer, breast MRI detects mammographically occult cancer in 50 % of cases with axillary metastases, regardless of breast density [31]. Any suspicious findings should be biopsied. MRI has a very low false-negative rate. Of approximately 40 women reported in the literature with isolated axillary adenocarcinoma and negative breast MRI findings, only 4 were found to have breast cancer at surgery or during follow-up [32].

With multimodality management involving breast surgery (mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery) with axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), chemotherapy, and radiation, such patients are potentially curable [33]. These patients have a 10-year survival of approximately 65 %, making this one of the most favorable subsets in CUP [24]. Although a negative MRI can identify patients for whom ALND with radiation may be sufficient, in the absence of a primary breast cancer, the management of the ipsilateral breast is unclear [9, 32]. In a population-based analysis, surgery or radiation of the ipsilateral breast showed improved survival compared with ALND alone [27]. Also, in retrospective studies, the actuarial freedom from appearance of a primary in the untreated breast was significantly lowered with radiation [34]. ALND followed by breast radiotherapy appears to be equivalent to mastectomy with respect to locoregional recurrence-free survival, recurrence/metastasis-free survival, and breast cancer-specific survival [35]. These studies should be evaluated with caution given their retrospective nature, and only a limited number of patients included in the series underwent breast MRI prior to therapy decision. An appropriately powered prospective study in this setting is unlikely; albeit knowing the limitations, breast radiation is often offered to CUP patients with a negative breast MRI. Likewise, although there are no prospective trials for use of adjuvant systemic therapy in this setting, retrospective data indicate that it is reasonable to treat these patients similarly to patients with corresponding nodal stage breast cancer [9, 36].

This management paradigm is changing as molecular profiling complements pathology as a diagnostic tool in this subset of patients. Not all women with axillary adenopathy do have occult breast cancer. Profiling for tissue of origin can help with treatment decisions especially if the immunohistochemistry does not correlate with breast cancer and ER, PR, and Her-2 status is negative.

Summary

Women presenting with CUP and isolated axillary lymphadenopathy are a unique favorable subset of CUP, in whom management should be designed in accordance with treatment of locally advanced breast cancer. When breast markers are not positive on immunohistochemistry, especially in patients with poorly differentiated carcinoma, it can present a challenge for management and most would treat it as breast cancer in the absence of an identifiable putative primary with additional studies. With aggressive local management (breast surgery and ALND with or without radiation) and chemotherapy, these patients are expected to have prolonged survival.

10.5 Papillary Carcinoma of the Peritoneal Cavity in Women

Case Study

A 54-year-old lady presented with progressively worsening abdominal pain for the past 3 weeks. She had no significant medical history, and total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed 12 years ago for uterine fibroids. CT abdomen and pelvis showed a 3.8 × 6 cm mass in the omentum, left of midline in the lower abdomen with some nonspecific lymphadenopathy (Fig. 10.3a, b). Mammography, upper GI endoscopy, and colonoscopy were performed and were normal. An ultrasound-guided biopsy of this omental mass showed a poorly differentiated carcinoma. The immunohistochemical profile was not specific and showed malignant cells positive for CK7 and ER (about 90 %) and negative for synaptophysin, CK20, TTF-1, CD56, PR, GCDFP15, P63, P40, mammaglobin, and CK5/CK6. Due to the presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis, additional staining was performed and showed tumor cells to be positive for WT-1 and PAX-8 and negative for inhibin. The histopathology and immunophenotype was most consistent with a high-grade serous carcinoma of Mullerian origin (peritoneal/ovary). CA 125 was found to be 220.5 U/ml (reference range: 0.0–35.0) (Fig. 10.3d). Preoperative PET scan showed FDG-avid disease in the peritoneum without any evidence of distant metastases (Fig. 10.3c). The patient underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, exploratory laparotomy, omentectomy, and resection of the anterior abdominal wall mass with optimal tumor reductive surgery. No additional metastatic disease was noted in the peritoneum. Pathology showed high-grade serous carcinoma. Postoperatively, CA 125 decreased to 89.1 U/ml (Fig. 10.3d). She was then treated with systemic chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel, but chemotherapy was held after two cycles due to poor tolerance. The patient has since been on surveillance for the past 1.5 years without any signs of local or distant recurrence.

Fig. 10.3

CT abdomen and pelvis (a and b) showing omental mass. PET Scan (c) showing solitary FDG-avid disease in the peritoneum. CA-125 trends (d) over the course of treatment

Peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma has been recognized as a phenotypic variant of familial ovarian cancer and is seen in patients with increased risk of ovarian cancer such as those with germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations [37]. These tumors have also been seen to occur after prophylactic oophorectomy [38]. Therefore, in women presenting with serous papillary peritoneal carcinoma, primary peritoneal carcinoma should be suspected [39, 40]. The clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of patients with primary peritoneal serous papillary carcinomas are similar to those of stage III–IV papillary serous ovarian carcinoma [41].

Pathological review may show a heterogeneous appearance with complex papillary or glandular architecture. Psammoma bodies may be present. The key feature is prominent mitotic activity, and many tumors can present as poorly differentiated carcinomas. The immunophenotype of this subset is typically positive for CK7, P53, WT-1, ER, and PAX-8 in most cases and negative for calretinin [42–45]. These tumors need to be distinguished from peritoneal mesotheliomas which are negative for Ber-EP4 and MOC-31 and positive for calretinin and D2-40 [46].

Combining optimal debulking with a platinum-based chemotherapy similar to that used for ovarian cancer is the most effective treatment. The median disease-free interval in these patients is about 15 months, and the median survival is about 21–23 months with a 5-year survival of 18 %, making the prognosis more favorable compared to the unfavorable CUP subset [40, 41]. The extent of cytoreduction is the most important prognostic indicator of survival in these patients, with median survival time of 20 months with residual tumor equal to or greater than 2 cm compared to 24 months with residual tumor less than 2 cm [41, 47]. Patients with this primary peritoneal adenocarcinoma presentation and widespread disease can also be given induction chemotherapy with paclitaxel-cisplatin/carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy [47]. Overall, the management for this subgroup should follow the guidelines for stage III–IV ovarian cancer with surgical cytoreduction and chemotherapy (platinum based and taxane based; Refs. [9, 48]).

Unfortunately, the majority of women with peritoneal carcinomatosis and CUP have disease without serous and Mullerian features and rather show mucin-producing or non-mucinous adenocarcinoma, some with signet ring cells. The primary site in these instances is most likely the GI tract (i.e., stomach, small bowel, appendix, colon, or pancreaticobiliary).

Summary

Poorly differentiated carcinoma/adenocarcinoma of unknown primary presenting with peritoneal involvement in women and having clinicopathological features suggestive of serous ovarian neoplasms represent a favorable subset of CUP similar to primary peritoneal carcinoma with long-term remission seen in about 15 % of cases. This subset should be treated as stage III–IV ovarian cancer using cytoreductive surgery and platinum-taxane-based chemotherapy.

10.6 Poorly Differentiated Carcinoma with Midline Distribution

Midline nodal CUP is thought to represent a subset of CUP with relatively favorable prognosis [49]. However, the definition of this entity varies considerably from one series to another, making this a group of heterogeneous disorders comprising multiple tumors types, especially germ cell tumors and lymphoma [50]. With progress in immunohistochemical techniques, the relevance of this subset is uncertain. Immunohistochemical stainings such as OCT4 are highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of germ cell tumors [51]. Similarly, antibodies to leukocyte common antigen (LCA) very reliably differentiate lymphomas from non-hematological malignancies [52]. Furthermore, the presence of 12p chromosomal gain (isochromosome 12p) is a diagnostic feature of extragonadal germ cell tumors [53].

Young patients presenting with poorly differentiated carcinoma in midline distribution should always be investigated for the possibility of extragonadal germ cell tumors and if they have features suggestive of germ cell tumors should be treated as having poor-risk germ cell tumor with platinum-based combination chemotherapy [9, 49]. In all these patients, the presence of a primary testicular tumor must be excluded using testicular ultrasound [54]. Serum tumor markers such as human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) can be helpful in suggesting the diagnosis of extragonadal germ cell tumor in these patients.

Due to traditionally high responses to platinum-based chemotherapy in germ cell tumors, these patients are expected to have favorable prognosis. The median survival in midline nodal CUP ranges from 8 to 23 months in literature, highlighting the heterogeneity of this subset [49]. In a series of 64 patients with poorly differentiated carcinoma or adenocarcinoma with predominantly midline nodal involvement, response rates of 48 % were seen with platinum-based chemotherapy [49]. Median survival of 12 months was reported for all patients [49]. However, in a subgroup of 15 male patients selected with more stringent clinical definition with the following criteria: age less than 50 years, tumor involving primarily midline nodal areas, rapid tumor growth, and histopathological diagnosis of undifferentiated or poorly differentiated carcinoma, median survival was reported to be 18 months [49].

Summary

Young patients with poorly differentiated carcinoma predominantly involving mediastinal, retroperitoneal lymph nodes should be evaluated for the possibility of extragonadal germ cell cancer syndrome with tumor markers, immunohistochemistry, and if needed chromosomal analysis and can be treated as per guidelines for poor-risk germ cell tumors with platinum-based combination chemotherapy.

10.7 Squamous Cell Carcinoma Involving Cervical Lymph Nodes

Squamous cell carcinomas constitute 5 % of all diagnosed CUP [2]. The clinical presentation can vary, but patients with cervical lymphadenopathy appear to have a favorable prognosis. Patients with cervical lymphadenopathy are managed as squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck, while those with inguinal lymphadenopathy need an approach similar to those for anogenital primaries. In patients with squamous cell carcinoma involving cervical lymph nodes with an initial occult primary, a primary will emerge in about 20 % of cases after definitive treatment [55, 56]. Although most patients with this subset are smokers, a small subset of these patients is HPV positive [57].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree