Chapter 28

Faltering Weight

Zofia Smith

Introduction

The term ‘failure to thrive’ was once used to describe infants and young children who failed to reach their expected growth. Over the last 15 years, more has been understood about poor weight gain and the term has been criticised for being pejorative [1]. The term ‘faltering weight’ has now been accepted as the term for infants who show a fall in weight or poor weight gain. However, some of the literature still refers to the term ‘failure to thrive’ (FTT).

Earlier definitions also focused on whether the cause of faltering weight was ‘organic’, with a medical diagnosis, or ‘non-organic’, related to unknown psychosocial factors. It is now clear from research that only 5% of cases of faltering weight have an underlying medical problem. The two categories are not mutually exclusive and undernutrition is recognised as the primary cause of poor weight gain in infancy [2].

Identification and prevalence of faltering weight

Faltering weight is identified in the main from interpretation of growth charts which show accurate weight and height measurements; this is still the most reasonable marker for diagnosis [3]. Guidelines on the 2009 UK-WHO growth charts suggest that a sustained drop of weight through two or more centile spaces is unusual (fewer than 2% of infants) and should be carefully assessed by the primary care team [4]. Several other patterns of faltering weight have been identified which suggest undernutrition (Table 28.1).

Table 28.1 Patterns of faltering weight

|

As well as weight and height, head circumference is a most useful indicator in the first 2 years. Height centile should be compared with the parental height as weight gain has been shown to correlate with parental height, suggesting that smaller parents have infants with poorer weight gain [5]. Mid upper arm circumference (MUAC), which indirectly assesses nutritional status by estimating body fat and muscle bulk, is also a useful measurement for children under 5 years (Table 28.2).

Table 28.2 Mid upper arm circumference of 1–5 year olds [6]

| <14.0 cm | Very likely to be a significantly malnourished child |

| 14.0–15.0 cm | May be malnourished (likelihood greater if age nearer to 5 years than 1 year) |

| >15.0 cm | Nutrition likely to be reasonable |

Although growth charts are the most likely way of identifying faltering weight, the following features may also be linked with poor weight gain:

- muscle wasting, poor skinfold thickness

- thin, wispy hair

- visible or prominent bones (e.g. pointed chin in a baby)

- pale complexion (could suggest iron deficiency)

- poor sleep pattern

- developmental delay (particularly in communication skills)

- emotional and behavioural issues (ranging from withdrawn/passive to active/chaotic with poor concentration)

Research has shown that health professionals do not always recognise faltering weight. Batchelor and Kerslake found that one in three children whose weight had fallen substantially were not identified [7]. There were various reasons for non-recognition: lack of awareness of the problem; well cared for children with no signs of physical neglect; no reported feeding difficulties; acceptance of children as small; under use of growth charts.

The incidence of faltering weight in the population depends very much on how faltering weight is defined. It is suggested that it affects 5% of infants in deprived inner city areas but also occurs across a wide social range [8].

Contributing factors

In the early years of life, energy and nutrient requirements are high to allow for rapid growth. Infants and young children are vulnerable at this time when there can be problems around feeding or, in a minority of cases, food is unavailable. For some children, medical conditions are clearly the principal reason for their undernutrition (Table 28.3) [1].

Table 28.3 Organic factors contributing to faltering weight

|

|

|

|

|

Despite an often seemingly adequate intake, gastrointestinal disorders may lead to faltering weight because of malabsorption, e.g. coeliac disease. Children with congenital cardiac or respiratory defects may show poor growth due to the breathing problems, anorexia or increased energy requirements caused by their disease.

Children with neurological dysfunction may have problems with oromotor development which can affect the ability to suck and swallow. They may also suffer from oral hypersensitivity and therefore refuse to feed. Children with metabolic disorders can present with faltering weight as a result of poor feeding or inability to utilise energy correctly. Faltering weight is common in infants born prematurely; their special nutritional needs and oromotor problems are reviewed separately (p. 101).

For the children with poor weight gain and no apparent medical problem, an inadequate intake of energy is still the underlying cause. There is increasing recognition of various possible factors contributing to an inadequate intake (Table 28.4).

Table 28.4 Factors contributing to inadequate intake

|

Early feeding problems

It is suggested that faltering weight is a result of chronic feeding difficulties [9] and feeding problems are the most commonly cited reason for faltering weight. For many infants, weight begins to falter around the time of weaning when a young infant’s oromotor skills develop, allowing the acceptance of new tastes and textures. If this opportunity is missed, the progression through weaning and the acceptance of more solid textures can be difficult, leading to over-dependence on milk. Intake is then restricted and is inappropriate for age with insufficient energy for normal growth. Excessive consumption of fluids, whether milk or juice, can exacerbate the problem [10, 11].

A young infant, particularly as weaning progresses, will show increasing independence and want to self-feed. They must be given the opportunity to develop these self-feeding skills. Where parents are unable to read these cues and continue to feed the child, poor intake or food refusal may occur.

In a population based study, children with faltering weight had significantly more feeding problems. These infants were introduced to solids and finger foods later than the control group and were identified as variable eaters with low appetite and poor feeding skills. These factors could lead to the onset and persistence of faltering weight [12]. One study reported the experiences of parents with children with faltering weight who had severe feeding difficulties. Parents described stressful mealtimes, children crying, clamping their lips, turning away, pushing food away, spitting out food and being sick [13].

Behavioural feeding problems, including food refusal, can happen at an early age and there are many contributing factors [14]. One of the earliest forms of infant communication occurs during feeding with carer and infant responding and reacting to each other. Parental feeding interaction, which might well be affected by worry, anxiety or concern about a child’s intake, will influence how a child reacts to food. In turn, clear cues from the child might not be noticed by the carer. For young infants with gastro-oesophageal reflux, food might well be associated with vomiting and pain. Feeding can then be an unpleasant experience, leading to food refusal. There are many reasons for food refusal including dental caries, extreme temperatures of food, inappropriately sized pieces, insensitive feeding or reluctance of parents to allow the child to feed itself and make the inevitable ‘mess’. Feeding problems often frustrate parents who will differ in their ways of dealing with it. This often causes great distress and disruption to family life. All this contributes to the persistence of faltering weight.

Family and maternal influences

Some studies have focused on psychosocial characteristics of the family and the environment of the child who has faltering weight. Parents’ inability to provide emotional nurturing may well contribute to the problem. Family conflict before the age of 7 has also been shown to have a strong and significant association with slow growth [15].

Maternal attitudes towards food and feeding have been shown to have an influence on the eating habits of children. McCann et al. reported that mothers of children whose weight faltered showed greater dietary restraint both concerning what they ate themselves and what they were prepared to offer their children [16]. In another study, infants of mothers who were both depressed and deprived showed poorer weight gain [17].

Poverty

Poverty is not a factor in isolation and there is little evidence to suggest an increased risk of faltering weight in the poorest [17], but there is a strong suggestion that larger families constitute a risk [5].

Neglect and abuse

Two population studies found that between 5% and 10% of children who had faltering weight had been registered for abuse or neglect [12, 18]. It is suggested that children in abusive or neglecting families are at an increased risk of faltering weight, but these families only represent a small proportion of all cases.

Outcomes for children with poor weight gain

Nutrition in the early years of life is a major determinant of growth and development and it influences future adult health [19]. Evidence suggests that poor weight gain from birth to 6–8 weeks of life is a stronger predictor of developmental delay than poor weight gain over the remainder of the first year [20]. A meta-analysis found that infants with early onset faltering weight were likely to be shorter and thinner than age matched peers, but there was little evidence of damaging consequences for growth and intellectual development. However, it was acknowledged that poor growth can be an important marker for the need for intervention for children where there is neglect, a medical condition, developmental problems or feeding issues [21]. Early home intervention has been reported as mitigating the effects of faltering weight [22].

Assessment of faltering weight

Health visitors, with appropriate training, are ideally placed to identify children with faltering weight when they are undertaking routine child health surveillance. A holistic assessment, preferably undertaken at home, should look at a child’s intake, feeding behaviour and family circumstances. The community paediatric dietitian will help to clarify any dietary concerns and assess nutritional adequacy. There might also be an oromotor skills assessment by a speech and language therapist.

When poor weight gain continues, a multidisciplinary team approach has been advocated where the medical and psychosocial aspects are combined into a clear focus on food and feeding [23, 24]. This will allow for a full paediatric assessment to be undertaken: medical assessment, taking a feeding history, assessment of current dietary intake, psychosocial and developmental aspects. Potential members of a multidisciplinary feeding team are

- community paediatrician

- community paediatric dietitian

- specialist health visitor

- clinical psychologist

- nurse/nursery nurse

- speech and language therapist (for some children)

Joint working enables discussion of individual cases and close cooperation between families and professionals. Clinical investigations only need to be undertaken if there are any suggestions of symptoms, in order to exclude organic disease and to reassure anxious parents.

Dietary assessment

It is important to construct a complete picture of all aspects of and influences on the child’s feeding. Early feeding history, together with the start and progression of solids, will help to identify if there were problems in the first year of life. Dietary recall with further information on the variety and the frequency of foods offered and eaten, mealtime routines and drinks taken through the day will all help to assess the child’s current intake. Information on the purchasing of food and its preparation within the home may also be revealing. Discussion with the parent will identify how long mealtimes last and whether they are stressful. Gathering background information will help to identify any difficulties experienced by the family.

There is little research on the dietary intake of children with faltering weight. One study raised the difficulties in collecting dietary information and suggested that only a minority of children with faltering weight will have dietary histories that are obviously inadequate, but that wider ranging nutritional assessment will be more revealing [25].

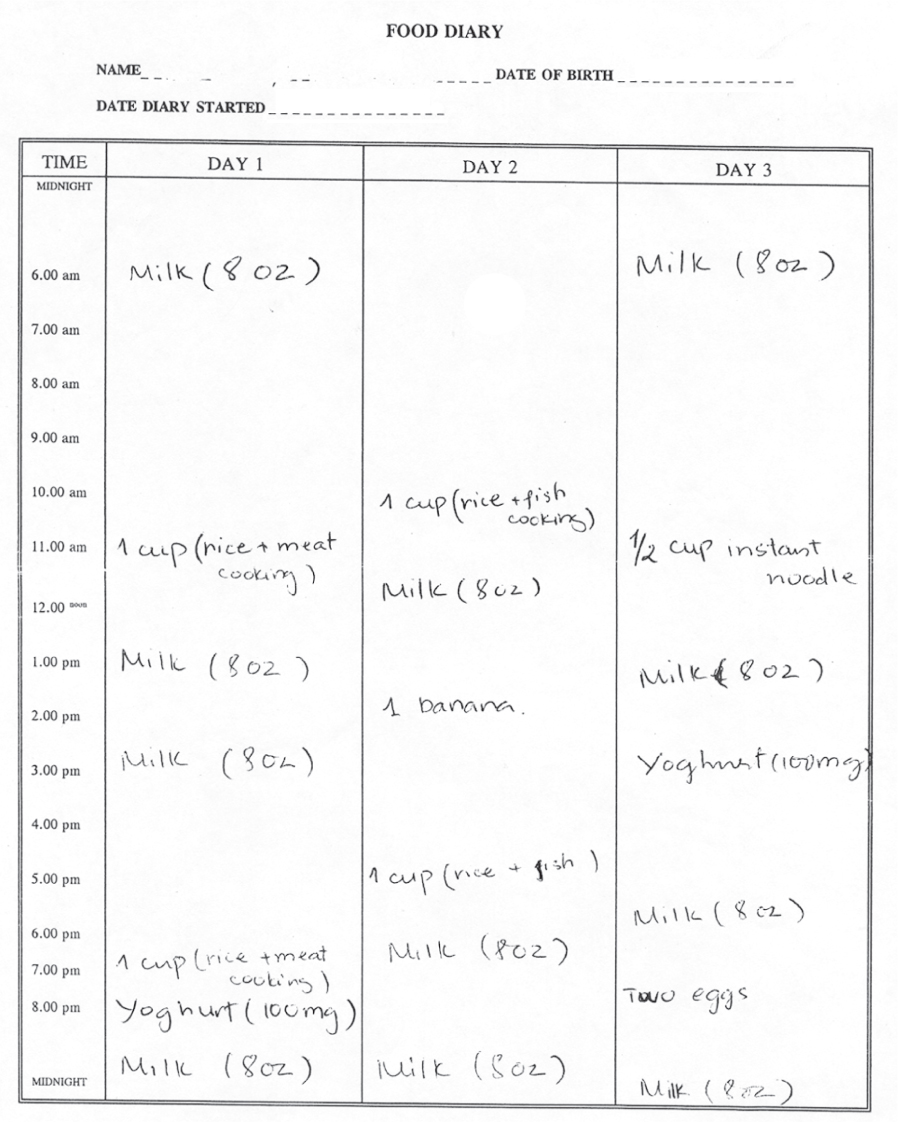

A food diary is a useful tool in nutritional assessments, revealing invaluable qualitative information as well as helping to establish the nature of dietary inadequacies [26]. Table 28.5 shows a food record of a 2-year-old child completed by the parent. This reveals the routine, frequency and limited range of foods as well as types and amounts of fluids. Immediate advice would be to ensure the child had an adequate intake of minerals and vitamins whilst urgent further assessment of feeding would need to be undertaken by a community dietitian and health visitor.

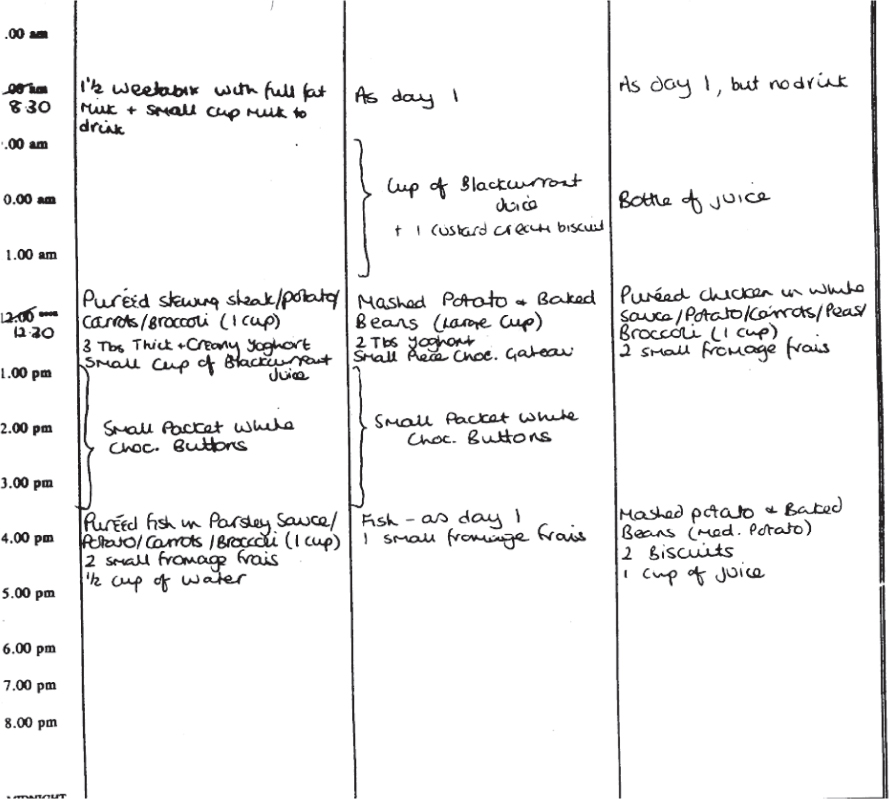

Table 28.6 shows a food record of an underweight 18-month-old child completed by a parent. This shows that the child is predominantly offered meals, food is puréed or mashed to give mainly softer textures, and bottles of juice are offered as drinks. Although the quantities taken cannot be seen from this information, the parent can be helped to think about the amounts of drinks offered and the age appropriateness of the food. Further discussion with the parent will need to clarify if these are typical days.

Observing a child eating is crucial to obtain more information about

- the seating of the child and parent positioning

- the child’s interest in its own food or food of other family members

- the quantity, texture and type of food offered and what is eaten

- the child’s desire or ability to feed or drink by themselves

- the child’s oromotor and self-feeding skills

- the interaction between the child and parent, including parental response to child’s cues

- communication between the child and parent, e.g. verbal encouragement

- the atmosphere and emotions at mealtime

- the interaction between the child and parent, including parental response to child’s cues

Some specialist teams, with parental agreement, will video a mealtime. The mealtime observation, when shared with the family, can allow the parents to see the feeding from a different perspective. A comment from one parent having viewed a feeding session was: ‘Well I’m not surprised she’s not eating. I didn’t realise I was so forceful. If someone tried to feed me like that, I wouldn’t eat either.’ When parents are able to suggest changes and contribute to the management plan, there is a greater chance of success.

Observation can also highlight ineffective ways of feeding an infant or young child (Table 28.7) and the issues can be sensitively raised with the parents.

Table 28.7 Poor feeding techniques

|

It is important to listen to parental concerns and their view should be taken into account. It is also useful to know who else is involved in the care and feeding of the child. For some children, and again with parental agreement, it is useful to observe the child’s behaviour around food in a setting other than home, e.g. nursery, children’s centre or school. This can help in identifying differences in eating and feeding, adding further valuable information.

Assessment of oromotor function

For a small number of children who may have neurodevelopmental problems or continue to exhibit food refusal and faltering weight, it is important for a speech and language therapist (SLT) to assess oromotor function. Such assessments, often in conjunction with video-fluoroscopy, will identify infants who are unable to coordinate the suck/swallow reflex. These children are likely to aspirate feeds and may require nasogastric or gastrostomy feeding. The SLT will also detect oral hypersensitivity and be able to help with desensitisation programmes.

Nutritional management

Nutritional requirements

A dietary intake which provides energy and protein requirements for age [27] will usually allow for maintenance of growth along a particular centile. Additional protein and energy will be required to allow for weight to improve. Guidelines suggest that the percentage of energy supplied from protein should be between 8.9% and 11.5% to provide optimal improvement of lean and fat mass [28]. Supplementing the diet with glucose polymers to increase energy density, hence providing a lower percentage of energy from protein, has been associated with higher rates of fat deposition.

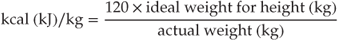

A formula for predicting energy requirements to improve weight gain in infants and young children has been suggested [29]:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree