Falls: Introduction

Falls are a major cause of morbidity in the geriatric population. Close to one-third of those age 65 years and older living at home suffer a fall each year. Among nursing homes residents, as many as half suffer a fall each year; 10% to 25% cause serious injuries. Accidents are the fifth leading cause of death in persons older than age 65, and falls account for two-thirds of these accidental deaths. Of deaths from falls in the United States, more than 70% occur in the population older than age 65. Fear of falling can adversely affect older persons’ functional status and overall quality of life. Repeated falls and consequent injuries can be important factors in the decision to institutionalize an older person.

Table 9–1 lists potential complications of falls. Fractures of the hip, femur, humerus, wrist, and ribs and painful soft tissue injuries are the most frequent physical complications. Many of these injuries will result in hospitalization, with the attendant risks of immobilization and iatrogenic illnesses (see Chapter 10). Fractures of the hip and lower extremities often lead to prolonged disability because of impaired mobility. A less common, but important, injury is subdural hematoma. Neurological symptoms and signs that develop days to weeks after a fall should prompt consideration of this treatable problem.

Injuries Painful soft tissue injuries Fractures Hip Femur Humerus Wrist Ribs Subdural hematoma Hospitalization Complications of immobilization (see Chap. 10) Risk of iatrogenic illnesses (see Chap. 5) Disability Impaired mobility because of physical injury Impaired mobility from fear, loss of self-confidence, and restriction of ambulation Increased risk of institutionalization Increased risk of death |

Even when the fall does not result in serious injury, substantial disability may result from fear of falling, loss of self-confidence, and restricted ambulation (either self-imposed or imposed by caregivers).

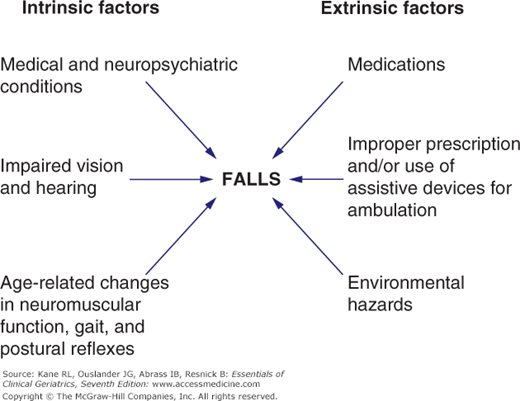

Many studies suggest that some falls can be prevented. The potential for prevention together with the use of falling as an indicator of underlying risk for disability make an understanding of the causes of falls and a practical approach to the evaluation and management of gait instability and fall risk important components of geriatric care. Similar to many other conditions in the geriatric population, factors that can contribute to or cause falls are multiple, and very often more than one of these factors play an important role in an individual fall (Fig. 9-1).

Aging and Instability

Several age-related factors contribute to instability and falls (Table 9–2). Most “accidental” falls are caused by one or a combination of these factors interacting with environmental hazards.

Changes in postural control and blood pressure Decreased proprioception Slower righting reflexes Decreased muscle tone Increased postural sway Orthostatic hypotension Postprandial hypotension Changes in gait Feet not picked up as high Men develop flexed posture and wide-based, short-stepped gait Women develop narrow-based, waddling gait Increased prevalence of pathologic conditions predisposing to instability Degenerative joint disease Fractures of hip and femur Stroke with residual deficits Muscle weakness from disuse and deconditioning Peripheral neuropathy Diseases or deformities of the feet Impaired vision Impaired hearing Impaired cognition and judgment Other specific disease processes (eg, cardiovascular disease, parkinsonism—see Table 9–3) Increased prevalence of conditions causing nocturia (eg, congestive heart failure, venous insufficiency) Increased prevalence of dementia |

Aging changes in postural control and gait probably play a major role in many falls among older persons. Increasing age is associated with diminished proprioceptive input, slower righting reflexes, diminished strength of muscles important in maintaining posture, and increased postural sway. All these changes can contribute to falling—especially the ability to avoid a fall after encountering an environmental hazard or an unexpected trip. Changes in gait also occur with increasing age. Although these changes may not be sufficient to be labeled truly pathologic, they can increase susceptibility to falls. In general, elderly people do not pick their feet up as high, thus increasing the tendency to trip. Elderly men tend to develop wide-based, short-stepped gaits; elderly women often walk with a narrow-based, waddling gait. These gait changes have been associated with white matter changes in the brain on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and with subsequent development of cognitive impairment.

Orthostatic hypotension (defined as a drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg or more when moving from a lying to a standing position) occurs in approximately 20% of older persons. Although not all older individuals with orthostatic hypotension are symptomatic, this impaired physiological response could play a role in causing instability and precipitating falls in a substantial proportion of patients. Older people can experience a postprandial fall in blood pressure as well. People with orthostatic and/or postprandial hypotension are at particular risk for near syncope and falls when treated with diuretics and antihypertensive drugs.

Several pathologic conditions that increase in prevalence with increasing age can contribute to instability and falling. Degenerative joint disease (especially of the neck, the lumbosacral spine, and the lower extremities) can cause pain, unstable joints, muscle weakness, and neurological disturbances. Healed fractures of the hip and femur can cause an abnormal and less steady gait. Residual muscle weakness or sensory deficits from a recent or remote stroke can also cause instability.

Muscle weakness as a result of disuse and deconditioning (caused by pain and/or lack of exercise) can contribute to an unsteady gait and impair the ability to right oneself after a loss of balance. Diminished sensory input, such as in diabetes and other peripheral neuropathies, visual disturbances, and impaired hearing diminish cues from the environment that normally contribute to stability and thus predispose to falls. Impaired cognitive function may result in the creation of, or wandering into, unsafe environments and may lead to falls. Podiatric problems (bunions, calluses, nail disease, joint deformities, etc.) that cause pain, deformities, and alterations in gait are common, correctable causes of instability. Other specific disease processes common in older people (such as Parkinson disease and cardiovascular disorders) can cause instability and falls and are discussed later in the chapter.

Causes of Falls in Older Persons

Table 9–3 outlines the multiple and often interacting causes of falls among older persons. More than half of all falls are related to medically diagnosed conditions, emphasizing the importance of a careful medical assessment for patients who fall (see below). Several studies have found a variety of risk factors for falls, including cognitive impairment, impaired lower extremity strength or function, gait and balance abnormalities, visual impairment, nocturia, and the number and nature of medications being taken. Frequently overlooked, environmental factors can increase susceptibility to falls and other accidents. Homes of elderly people are often full of environmental hazards (Table 9–4). Unstable furniture, rickety stairs with inadequate railings, throw rugs and frayed carpets, and poor lighting should be identified on home visits. Several factors are associated with falls among older nursing home residents (Table 9–5). Awareness of these factors can help prevent morbidity and mortality in these settings. Several factors can hinder precise identification of the specific causes for falls. These factors include lack of witnesses, inability of the older person to recall the circumstances surrounding the event, the transient nature of several causes (eg, arrhythmia, transient ischemic attack [TIA], postural hypotension), and the fact that the majority of elderly people who fall do not seek medical attention. Somewhat more detailed information is available on the circumstances surrounding falls in nursing homes (see Table 9–5).

Accidents True accidents (trips, slips, etc.) Interactions between environmental hazards and factors increasing susceptibility (see Table 9–2) Syncope (sudden loss of consciousness) Drop attacks (sudden leg weaknesses without loss of consciousness) Dizziness and/or vertigo Vestibular disease Central nervous system disease Orthostatic hypotension Hypovolemia or low cardiac output Autonomic dysfunction Impaired venous return Prolonged bed rest Drug-induced hypotension Postprandial hypotension Drug-related causes Antihypertensives Antidepressants Antiparkinsonian Diuretics Sedatives Antipsychotics Hypoglycemics Alcohol Specific disease processes Acute illness of any kind (“premonitory fall”) Cardiovascular Arrhythmias Valvular heart disease (aortic stenosis) Carotid sinus hypersensitivity Neurological causes TIA Stroke (acute) Seizure disorder Parkinson disease Cervical or lumbar spondylosis (with spinal cord or nerve root compression) Cerebellar disease Normal-pressure hydrocephalus (gait disorder) Central nervous system lesions (eg, tumor, subdural hematoma) Urinary Overactive bladder Urge incontinence Nocturia |

Old, unstable, and low-lying furniture Beds and toilets of inappropriate height Unavailability of grab bars Uneven or poorly demarcated stairs and inadequate railing Throw rugs, frayed carpets, cords, wires Slippery floors and bathtubs Inadequate lighting, glare Cracked and uneven sidewalks Pets that get under foot |

Recent admission Dementia Hip flexor muscle weakness Certain activities (toileting, getting out of bed) Psychotropic drugs causing daytime sedation Cardiovascular medications (vasodilators, antihypertensives, diuretics) Polypharmacy Low staff-patient ratio Unsupervised activities Unsafe furniture Slippery floors |

Close to half of all falls can be classified as accidental. Usually an accidental trip or a slip can be precipitated by an environmental hazard, often in conjunction with factors listed in Table 9–2. Addressing the environmental hazards begins with a careful assessment of the environment. Some older persons have developed a strong attachment to their cluttered surroundings and may need active encouragement to make the necessary changes, but many may simply take such environmental risks for granted until they are specifically identified.

Syncope, “drop attacks,” and “dizziness” are commonly cited causes of falls in older persons. If there is a clear history of loss of consciousness, a cause for true syncope should be sought. Although the complete differential diagnosis of syncope is beyond the scope of this chapter, some of the more common causes of syncope in older people include vasovagal responses, carotid sinus hypersensitivity, cardiovascular disorders (eg, bradycardia, tachyarrhythmias, aortic stenosis), acute neurological events (eg, TIA, stroke, seizure), pulmonary embolus, and metabolic disturbances (eg, hypoxia, hypoglycemia). A precise cause for syncope may remain unidentified in 40% to 60% of older patients.

Drop attacks, described as sudden leg weakness causing a fall without loss of consciousness, are often attributed to vertebrobasilar insufficiency and often precipitated by a change in head position. Only a small proportion of older people who fall have truly had a drop attack; the underlying pathophysiology is poorly understood, and care should be taken to rule out other causes.

Dizziness and unsteadiness are common complaints among elderly people who fall (as well as those who do not). A feeling of light-headedness can be associated with several different disorders but is a nonspecific symptom and should be interpreted with caution. Patients complaining of light-headedness should be carefully evaluated for postural hypotension and intravascular volume depletion.

Vertigo (a sensation of rotational movement), on the other hand, is a more specific symptom and is probably an uncommon precipitant of falls in the elderly. It is most commonly associated with disorders of the inner ear, such as acute labyrinthitis, Ménière disease, and benign positional vertigo. Vertebrobasilar ischemia and infarction and cerebellar infarction can also cause vertigo. Patients with vertigo caused by organic disorders often have nystagmus, which can be observed by having the patient quickly lie down and turning the patient’s head to the side in one motion. Many older patients with symptoms of dizziness and unsteadiness are anxious, depressed, and chronically afraid of falling, and the evaluation of their symptoms is quite difficult. Some patients, especially those with symptoms suggestive of vertigo, will benefit from a thorough otological examination including auditory testing, which may help clarify the symptoms and differentiate inner ear from central nervous system (CNS) involvement.