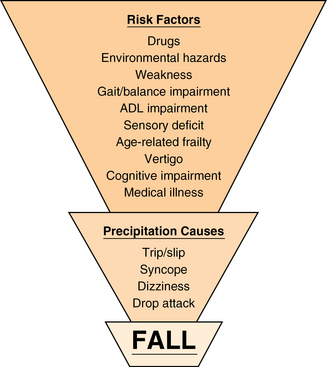

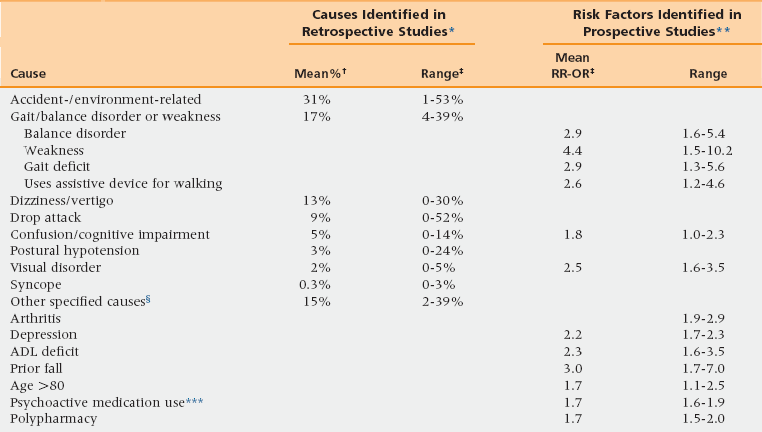

20 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the incidence of falls among older adults. • List the major risk factors for falls. • Assess an older adult who has fallen. • Identify effective evidence-based fall prevention interventions. • Describe the American Geriatrics Society’s clinical practice guideline for fall prevention. • Develop an individualized plan for preventing future falls. Falls rank high among serious clinical problems facing older adults. They cause substantial morbidity and mortality and contribute to immobility and premature nursing home placement. Unintentional injuries are a leading cause of death in older adults, and falls comprise two thirds of these deaths. In the United States, about three fourths of deaths resulting from falls occur in the 13% of the population that is aged 65 years and older, making injurious falls a true geriatric syndrome. At least a third of older persons living at home will fall at least once in a year, and about 1 in 40 will be hospitalized. Of those hospitalized after a fall, nearly half will die within a year. Repeated falls and instability are common precipitators of nursing home admission. Within long-term care institutions, fall rates are even higher, averaging almost two falls per patient year. Moreover, falls in institutions more commonly have serious complications—10% to 25% are associated with a fracture or laceration.1 The way a person falls often determines the type of injury sustained. Wrist fractures usually result from falls onto an outstretched hand; hip fractures typically result from falls to the side; and backward falls onto the buttocks have a much lower fracture rate.2 Wrist fractures are more common than hip fractures in people between ages 65 and 75, whereas hip fractures predominate after age 75, probably because of slowed reflexes and loss of ability to protect the hip by “breaking the fall” with one’s hands after age 75. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in three adults aged 65 and older falls each year. Of these, 20% to 30% suffer moderate to severe injuries that reduce their functional capacity and increase their mortality risk, and 662,000 are hospitalized annually. The costs of falls are immense: in 2001 Medicare costs per fall averaged between $9,113 and $13,507, and by 2020 the annual direct and indirect cost of fall injuries is expected to reach $54.9 billion (in 2007 dollars).3 The U.S. Public Health Service has estimated that two thirds of deaths resulting from falls are potentially preventable, based on a retrospective analysis of causes and circumstances of serious falls. Identifying and eliminating environmental risks in homes or institutions could prevent many falls caused primarily by environmental factors, and adequate medical evaluation and treatment for underlying medical risk factors, such as unstable gait and disabling medical conditions, could prevent many medically related falls. There are many precipitating causes of falls in older persons, as shown in Table 20-1, which summarizes data from 12 of the largest retrospective studies. Drawing conclusions across studies is limited by several factors, including differences in classification methods, patient recall, and the multifactorial nature of most falls. Although accidents or environmental hazards are the most frequently cited causes of falls, this is misleading because most falls attributed to accidents really stem from an interaction between environmental hazards and increased individual susceptibility to hazards from accumulated effects of age and disease. Older people tend to have less coordinated gaits than do younger people. Posture control, body-orienting reflexes, muscle strength and tone, and step height all decline with aging and impair ability to avoid a fall after an unexpected trip or slip. Age-associated changes such as impairment of vision, hearing, and memory also tend to increase the number of trips and stumbles. Because most elderly individuals have multiple identifiable risk factors predisposing to falls, the exact cause can often be difficult to determine. TABLE 20-1 Factors Associated with Falls in Elderly Adults *Summary of 12 studies that carefully evaluated elderly persons after a fall and specified a “most likely” cause. Adapted from Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR. The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med 2002;18:141-58. **Summary of 16 controlled studies. Adapted from Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR. The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med 2002;18:141-58. ***Data from Bloch F, Thibaud M, Tournoux-Facon C, et al. Estimation of the risk factors for falls in the elderly: Can meta-analysis provide a valid answer? Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013;13(2)250-63. §This category includes arthritis, acute illness, drugs, alcohol, pain, epilepsy, and falling from bed. †Mean percent calculated from the 3628 reported falls. ‡Ranges indicate the percentages reported in each of the 12 studies. In addition to looking retrospectively for causes, investigators have sought to identify specific risk factors that place individuals at increased likelihood of falling. In many ways, knowing about risk factors that can be identified before a fall is much more useful than identifying precipitating causes retrospectively, because prefall identification can allow preventive strategies to be devised and instituted. Table 20-1 also lists the major fall risk factors, displaying their relative importance in terms of mean odds ratio or relative risk, pooled from a large number of such studies.1 The most important of these risk factors are muscle weakness, fall history, problems with gait and balance, visual deficits, arthritis, functional impairment, depression, and cognitive impairments. It should be noted that some of these risk factors are directly involved in causing falls (e.g., weakness, gait and balance disorders), whereas others are markers of other underlying causes (e.g., prior falls, assistive device, age >80). More recent analyses have confirmed these risk factors as well as the additional importance of taking psychoactive medications and polypharmacy, which are associated with odds ratios of between 1.5 and 1.8.4 Figure 20-1 provides a visual schematic of the complex relationship among and between selected risk factors, precipitating causes, and falls. Such multifactorial causality is typical of geriatric syndromes generally, which explains why fall prevention necessitates a systematic, multidimensional evaluation. Leg weakness, one of the most important risk factors, is an extremely common finding among the aged population. Weakness often arises from deconditioning resulting from limited physical activity or prolonged bed rest, together with chronic debilitating medical conditions such as heart failure, stroke, or pulmonary disease, plus some age-related loss of muscle units. As a whole, healthy older people score 20% to 40% lower on strength tests than young adults,5 and the reported prevalence of leg weakness was 57% among residents of an assisted living facility,6 and more than 80% in a skilled nursing facility.7 Gait and balance disorders are also extremely common among older adults, affecting between 20% and 50% of people older than age 65 years,8 and are associated with a threefold increase in fall risk.4 A simple screening test of gait and balance function, such as the Timed Up and Go or Tinetti’s gait and balance test, is often useful in identifying risk and documenting need for treatment.6 Possibly even more important than identifying risk factors for falling per se is identifying risk factors for injurious falls, because most falls do not result in injury. Risk factors associated with injurious falls are the same as for falls in general, with the addition of female sex and low body mass, which are both related to osteoporosis.2 Most of the factors listed in Table 20-1 are amenable to improvement, suggesting ways that many falls can be prevented; moreover, the effectiveness of preventive strategies has been documented in a number of studies.

Falls

Prevalence and impact

Precipitating causes and risk factors for falls

Falls