Key Points

- 1.

Fallopian tube cancer (FTC) was historically thought to be a rare cancer. Now, most high-grade serous carcinomas are thought to arise from the fallopian tube as opposed to the ovary.

- 2.

The triad of pain, metrorrhagia, and leukorrhea is considered pathognomonic for FTC.

- 3.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers are at increased risk for FTC and should undergo extensive sectioning of the fallopian tubes during risk-reducing surgery.

- 4.

Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is a precursor lesion to high-grade serous carcinoma.

- 5.

Early salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy is currently being studied and may become an option in high-risk women to decrease mortality and maintain quality of life.

Introduction

Primary fallopian tube cancer (FTC) was traditionally considered an exceedingly rare gynecologic malignancy. Few pelvic serous tumors met rather strict diagnostic criteria for FTC, and the disease site was overshadowed by the clinicopathologically similar and far more common high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC). Over the past decade, mounting evidence implicates carcinogenic processes beginning in the fallopian tube as the true origin of the majority of extrauterine high-grade serous carcinomas (HGSCs) inclusive of both HGSOC and primary peritoneal carcinoma (PPC). Indeed, the most recent International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) staging has recognized the commonality of these tumors in a unified staging system, and a broad international collaboration recommended fairly dramatic changes for assigning the site of origin for HGSC aligning with a paradigm of fallopian tube origin. This chapter describes FTC from what could be considered a historical perspective followed by a discussion of the precursor lesions and additional evidence leading to current models of carcinogenesis of FTC and by extension most extrauterine HGSCs.

Traditional Characteristics

Epidemiology, Classification, and Etiology

Based on primary site classifications set forth by Hu and later modified by Sedlis, adenocarcinoma of the fallopian tube accounted for fewer than 0.2% of cancer diagnoses among women annually with an incidence of 0.41 per 100,000. The most complete systematic review to date comparing FTC versus HGSOC found few significant differences in FTC and HGSOC relative to risk factors, clinicopathology, and molecular biology. Notably, the reviewed studies defined FTC in traditional terms as set forth by Hu and later Sedlis.

In 1950, Hu and colleagues suggested diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of tubal cancer: (1) the main tumor grossly should be in the fallopian tube; (2) histologically, the tubal mucosa should be involved with a papillary pattern; and (3) if the tubal wall is involved to a large extent, transition from benign to malignant tubal epithelium should be identified. Sedlis and colleagues modified these criteria in 1978: (1) the main tumor arises from the endosalpinx, (2) the histologic pattern reproduces the epithelium of tubal mucosa, (3) transition from the benign to malignant tubal epithelium is demonstrable, and (4) the ovaries or endometrium are either normal or contain a tumor that is smaller than the tumor in the tube.

Using the above definitions, a few characteristics relative to both risk factors and presentation are uniquely associated with primary FTC. A number of investigators implicate chronic tubal inflammation in tubal carcinogenesis. The initial association was with tuberculosis, and sporadic reports of fallopian tube carcinoma with coexisting tubercular salpingitis continue. Although histologic features of old pelvic inflammatory disease or endometriosis are frequently noted on examination of the tube and changes consistent with chronic healed salpingitis have been found in the contralateral tube of patients with unilateral FTC, evidence supporting such inflammatory changes as precursors to the development of carcinoma is inconsistent.

Symptoms and Signs

Classic symptoms of FTC include vaginal bleeding or discharge or lower abdominal pain. In many cases, these symptoms are vague and nonspecific. Vaginal bleeding is the most commonly reported symptom of FTC and is present in approximately 50% of the patients. Vaginal bleeding is caused by blood that accumulates from the lesion in the fallopian tube, which subsequently passes into the uterine cavity and finally exits into the vagina. Because FTC occurs most frequently after menopause, postmenopausal bleeding is common. Although carcinoma of the endometrium is the first consideration, FTC should be considered if the results of dilation and curettage are negative and symptoms persist.

Pain, often colicky, is frequently a symptom in tubal carcinoma and often accompanies vaginal bleeding. The pain is caused by distension of the tubal wall and stimulation of peristaltic activity. This pain, in many cases, is relieved with the passage of blood or watery discharge. Vaginal discharge, which is usually clear, occurs in approximately 25% of patients with tubal carcinoma. The triad of pain, metrorrhagia, and leukorrhea is considered pathognomonic for tubal carcinoma, but it occurs infrequently. Pain combined with a profuse, watery vaginal discharge, referred to as hydrops tubae profluens, is reported to be present in fewer than 5% of cases. If a patient is examined during the time that hydrops tubae profluens is present, a palpable pelvic mass may be found. The mass can decrease during the examination while the watery discharge continues. With the cessation of watery discharge and decrease in pelvic mass, the pain also decreases. Hydrops tubae profluens is caused by the effusion produced by the tumor that accumulates within the tube and causes the distension, which in turn produces the colicky pain.

Delay of diagnosis appears to be common due to nonspecific findings and overlap with ovarian cancer features. In a study by Eddy and associates, symptoms had been present for as long as 48 months. Half of the patients had symptoms for 2 months or longer. Semrad and colleagues noted a delay from the onset of symptoms to the diagnosis of an average of 4 months in about half of their patients. Peters and colleagues reported that 14% of patients were asymptomatic in their series of 115 patients.

Malignant cells are found in 11% to 23% of cervical cytologic preparations in patients with tubal cancer. In patients with hydrops tubae profluens, the chance of obtaining malignant cells should be relatively high. The identification of psammoma bodies in cervical cytology of postmenopausal women is often a sign of uterine or clear cell carcinoma, with serous fallopian tube or ovarian cancer occasionally being identified as the source.

Emerging Paradigms

As noted previously, until relatively recently, the prevailing view of extrauterine HGSC was that FTC was relatively rare and the majority of these cancers formed in the ovary, perhaps in cortical inclusion cysts. The major challenge to this theory was the lack of an identifiable precursor lesion despite decades of interrogation of the ovarian surface epithelium.

Fallopian Tube Cancer and BRCA Mutations

In the late 1990s, a number of reports emerged of FTCs associated with germline mutations in BRCA . Piek and colleagues, responding to these reports of FTC associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and their own molecular evidence that FTC was part of the cancer spectrum in BRCA mutation carriers, began screening serial sections of fallopian tubes removed during risk-reducing surgeries of women determined to be at high genetic risk of ovarian cancer. In 2001, they published their findings of the presence of dysplasia in the fallopian tubes of six of 12 cases and hyperplastic changes in an additional five with no corresponding abnormalities in 13 control cases. The provocative findings provided evidence for hyperplastic or dysplastic changes occurring in the carcinogenesis sequence of FTC and recommendations that risk-reducing surgery include both the ovaries and fallopian tubes and furthermore that both should be examined in all such cases to “attain more insight into BRCA1 -related oncogenesis.”

Occult or Intraepithelial Fallopian Tube Cancer Found During Risk-Reducing Surgery

Accumulating evidence and Piek et al.’s initial report prompted increased pathologic scrutiny of the fallopian tubes at the time of risk-reducing surgeries. Investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana Farber Cancer Institute developed the Sectioning and Extensively Examining the FIMbria (SEE-FIM) protocol in which the fallopian tubes are sectioned at 2- to 3-mm intervals and examined histologically with lengthwise sectioning of the fimbriated portion to maximize exposure of tubal plicae. When reviewing their series of 122 BRCA -positive patients undergoing risk-reducing surgery, these investigators found seven (5.7%) patients with occult malignancy, all of which originated in the distal fallopian tube. Additionally, six of the cancers were accompanied by a noninvasive component.

A number of other reports during this same decade corroborated the experience, although reported rates of occult malignancy varied because of differences in study populations, pathology processing, and diagnosis. The majority of occult lesions identified were invasive and noninvasive cancers in the fallopian tubes. The best estimate to date of invasive or intraepithelial ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal neoplasms in the genetically high-risk population is from the surgical intervention arm of Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Protocol 0199 (GOG 0199), also known as the National Ovarian Cancer Prevention and Early Detection Study. This prospective trial found a 4.6% risk in BRCA1 and 3.5% risk in BRCA2 mutation carriers. The primary sites were assigned based on distribution and extent of tumor unless an intraepithelial lesion of the fallopian tube was identified, in which case it was designated as tubal cancer. Of the 25 (of 966) lesions identified, 10 were designated ovarian, 10 were designated tubal, and five were designated primary peritoneal. The authors acknowledge that the use of more sensitive sectioning protocols, combined with growing diagnostic acumen, may prove their estimates of tubal neoplasia low.

Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinoma

The dysplastic tubal cells initially identified are now more commonly referred to as tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (TIC) or serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC). TICs are distinguished from normal mucosa by variably stratified epithelium with nuclear enlargement and atypia, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli, variable loss of cell polarity, and mitotic activity. Hyperchromasia, irregular nuclear membranes and chromatin distribution, and absence of cilia also characterize TICs.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) may be useful adjuncts in diagnosis. An elevated Ki-67 labeling index (>10%) and either intense or absent p53 staining (both correlate closely with mutation) support the diagnosis of TIC. Somatic mutations of p53 are the most common mutations in HGSC and are detected in more than 90% of TICs. Whereas the majority are missense mutations that correlate with intense and diffuse p53 immunoreactivity, frameshift, nonsense, and splicing junction mutations are associated with complete loss of p53 staining.

Strongly p53-positive, benign-appearing epithelium, described by Lee and colleagues as “p53 signatures” may be an even earlier event in serous carcinogenesis than TICs. These investigators demonstrated that these signatures were equally common in nonneoplastic tubes from women with and without BRCA mutations but more frequently present and multifocal in fallopian tubes with STIC. These signatures were much more common in the secretory cells of the fimbriae similar to TICs and often represented reproducible p53 mutations. In laser-capture microdissected (LCM) specimens, they also demonstrated that TICs and their associated ovarian cancers shared identical mutations and in one case demonstrated an identical mutation between the p53 signature and a contiguous TIC.

Despite the characteristics of STICs noted, the recognition of these lesions remains challenging, and the spectrum of changes within the fallopian tube can be difficult to interpret. In an effort to establish a reproducible classification for STIC, Visvanathan led a group of six gynecologic pathologists from four academic institutions through serial independent reviews to establish a reproducible algorithm. Intraobserver reliability was only fair for STIC versus not STIC when classification was based on morphologic criteria alone. An algorithm incorporating morphology and IHC for p53 and Ki-67 resulted in substantial agreement and provided the basis for a standardized, and later validated, classification of STIC for clinical diagnosis and future investigations.

Fallopian Tube Cancer and Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinoma Beyond BRCA

Building on the findings from high-risk populations, in 2007, Kindelberger and colleagues published the first study extensively examining the fallopian tubes (SEE-FIM protocol) in a consecutive series of pelvic serous carcinoma from patient not necessarily known to be at high risk. Of 55 evaluable cases, 75% had endosalpingeal involvement, and of these, 71% (29 of 41) had a coexisting STIC. Tumors classified as HGSOC by conventional criteria based on disease distribution often involved the endosalpinx and contained TICs (71% and 48%, respectively, of 42 cases). Five of five cases of ovarian cancer with concurrent TICs contained identical p53 mutations, supporting their clonality.

Przybycin and colleagues similarly examined a series of 52 pelvic (nonuterine) gynecologic cancers in which fallopian tube tissue was available for extensive examination. TIC was identified in 28 (60%) of 47 HGSCs, and because TIC was associated exclusively with this histology, they suggested the more specific term serous TIC or STIC . STICs in the absence of invasive carcinoma in the same tube was identified in seven (30%) of cases. By including STIC as supplemental criteria for extrauterine HGSC, the rate of FTC increased from 13% by conventional criteria to 64%. More extensive LCM examinations of STICs by this same group confirmed the clonal relationships of p53 mutations in STICS and concurrent HGSOCs. Additionally, they demonstrated telomere shortening, an early change in carcinogenesis, in STICs compared with their concurrent ovarian cancers, further supporting the primary role of the fallopian tube in high-grade serous carcinogenesis.

In 2014, Singh and colleagues proposed new guidelines for assigning the primary site of HGSC intended as an evolutionary change based on current understanding of the state of the science. Their intent was to build on the 2014 FIGO staging revision, which unified staging but did not unify nomenclature under an umbrella term (eg, pelvic serous carcinoma ) or provide specific guidance for primary site assignment. Indeed, there were numerous examples in which, depending on philosophy, different pathologists might assign the same clinical case as tubal, ovarian, primary peritoneal, tubo-ovarian, or undesignated in the new system. To avoid giving different diagnostic labels to the same disease in different centers, Singh et al. made a number of recommendations, offering a standard and systematic approach based on current knowledge. Among the most important recommendations was that the fallopian tubes should be sampled by a SEE-FIM–like protocol in all cases of HGSC and that any cases with STIC should be classified as tubal carcinoma.

The following year, this same group published an assessment of their system for primary site assignment in HGSC of the fallopian tube, ovary, and peritoneum. They retrospectively assessed 151 HGSC (both chemonaive and postneoadjuvant chemotherapy) of which 68% of cases were previously considered ovarian primaries. Using the new guidelines, they rendered a revised diagnosis of fallopian tube primary in 74% of cases. In a prospective cohort of 111 HGSC cases, a majority of which were advanced stage, they classified 79% as fallopian tube primaries and only 14% as ovarian primaries. There were fewer cases of primary FTCs diagnosed after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and more diagnosed as primary peritoneal or undetermined potentially resulting from regression of small lesions in the fallopian tube. In chemonaive cases, ovarian involvement was bilateral in 62% of cases, but fallopian tube involvement was bilateral in only 16%, lending further evidence that ovarian disease is metastatic instead of primary. The proposed system combined with the revised FIGO staging system provided uniform and reproducible site assignment while classifying most HGSC as fallopian tube primaries.

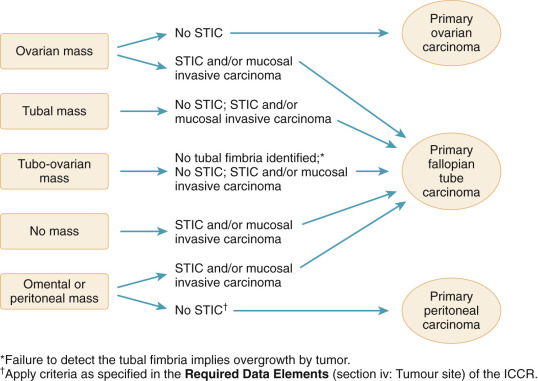

Building on the above work, in 2015, the International Collaboration on Cancer Report (ICCR) published recommendations on the classification of peritoneal, ovarian, and fallopian tube carcinomas ( Fig. 13.1 ). In this algorithm, any case with STIC and associated cancer involving the ovary, fallopian tube, or peritoneum should be classified as fallopian tube primary with classification using conventional criteria only if they lack STIC. The recommendations also conveyed that failure to identify fallopian tube fimbriae implied overgrowth by a fallopian tube carcinoma, and therefore careful attention to identify a fallopian tube in cases of an adnexal mass is important for accurate classification. Aberrant staining of p53 and Mindbomb E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase 1 (MIB1) is often found in association with STIC and therefore may prove helpful in confirming the diagnostic presence of the preinvasive lesion in questionable cases.