- 12.1 Introduction

- Conjunctival sac

- The globe

- Conjunctival sac

- 12.2 Conjunctivitis

- 12.2.1 Conjunctival infection

- 12.2.2 Allergic conjunctivitis

- 12.2.3 Autoimmune conjunctivitis

- 12.2.4 Stevens–Johnson syndrome

- 12.2.5 Other causes of conjunctivitis

- 12.2.1 Conjunctival infection

- 12.3 Keratitis

- 12.4 Scleritis

- 12.5 Uveitis

- 12.5.1 Anterior uveitis

- 12.5.2 Posterior uveitis

- 12.5.3 Uveitis following trauma

- 12.5.1 Anterior uveitis

Visit the companion website at www.immunologyclinic.com to download cases on these topics.

Visit the companion website at www.immunologyclinic.com to download cases on these topics.

12.1 Introduction

The eye is a fragile and complex organ, whose physiological function is intolerant of any distortion in structure. Immunological defence mechanisms within the eye need to strike a delicate balance between exclusion or rapid elimination of invading pathogens and the need to minimize excessive inflammation within the eye, which might disrupt transmission of light, impair retinal processing or cause damage to ocular tissue. For this reason, the eye relies heavily upon mechanical or physical barriers to infection.

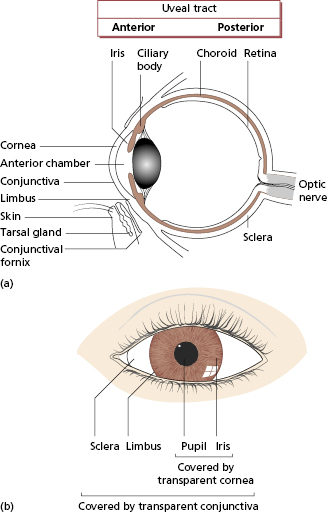

Immunologically, the eye can be divided into two major compartments: the conjunctival sac and the globe (Fig. 12.1).

Fig. 12.1 Anatomy of the eye. (a) In lateral section (only the lower eyelid is shown). (b) Frontal view (left side).

Conjunctival sac

The conjunctival sac has similar defence mechanisms to the skin and upper respiratory tract mucosa and is affected by similar diseases (Table 12.1). The conjunctival sac is the main site for entry of antigen into the eye. The major physical barriers to antigen entry are blinking and the free flow and drainage of tears. These physical factors are supplemented by antimicrobial factors within tears such as immunoglobulin (Ig)A and lysozyme. The conjunctiva can respond briskly to local irritation or injury, being highly vascular and containing mast cells. As in other sites, persistence of inflammation within the eye leads to the accumulation of chronic inflammatory cells, i.e. activated T and B cells and macrophages.

Table 12.1 Conjunctivitis and types of hypersensitivity

| Disease | Mechanism of hypersensitivity | Aetiology |

|---|---|---|

| Seasonal conjunctivitis | IgE-mediated (type I)* | Grass pollens + other antigens |

| Vernal conjunctivitis | IgE-mediated plus Th2 cells | Air-borne allergens |

| Atopic keratoconjunctivitis | Atopic (probably Th2 cells) | Ocular equivalent of atopic dermatitis |

| Cicatrizing conjunctivitis (pemphigoid) | Antibody on conjunctival basement membrane (type II) | Autoimmune |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome | Immune complex (type III) | Drug-reaction or unknown |

| Sarcoidosis | Granuloma (type IV) | Unknown |

| Contact dermatoconjunctivitis | Cellular immune reactions (type IV) | Drugs, cosmetics, contact lens solutions |

*Types I–IV refer to the Gell and Coombs’ classification; see Chapter 1.

The globe

The anatomy of the globe is summarized in Fig. 12.1. Two principal types of tissue are present: avascular tissues (cornea, lens, vitreous and sclera) and highly vascular tissues (the uveal tract, the posterior part of which is closely associated with the retina). Historically, the globe was regarded as invisible from the immune system (immunologically privileged, Chapter 5) because of a lack of lymphatic drainage, the presence of an endothelial blood–eye barrier, and the avascular nature of much of the globe’s contents. This physical separation of the eye and the immune system is important in preventing autoimmune disease within the eye, but it is now known that active suppression of immune responses is also of major importance in limiting inflammation within the globe.

Antigens can potentially enter the globe via the sclera, cornea, optic nerve or via the uveal tract. The tough physical barrier of the avascular tissues can normally exclude most antigens, provided conjunctival function is normal. The uveal tract, however, is highly vascular and has the capacity for trapping blood-borne antigens or microorganisms, a property that is shared with other highly vascular structures such as the glomerulus. As in the kidney, this is limited by the presence of tight junctions between uveal endothelial cells, which usually limit extravasation of cells or plasma. This blood–eye barrier may, however, break down in response to injury of many kinds.

If antigen does gain access to the globe, immune responses to that antigen are likely to be reduced or inhibited. Multiple mechanisms underlie this downregulation: immunosuppressive cytokines such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β are present within the eye, but cells throughout the cornea express high levels of a protein called Fas ligand (FasL), which will bind to any cells expressing its receptor, Fas, and trigger apoptosis in the Fas-bearing cells. Since Fas is richly expressed upon most cells which migrate into sites of inflammation, such as activated T cells, macrophages and neutrophils, this mechanism limits inflammation within the eye. FasL/Fas interactions also help to maintain tolerance within the eye, since autoreactive T cells entering the eye are deleted. Disruption of this process may contribute to autoimmune and hypersensitivity disease within the eye.

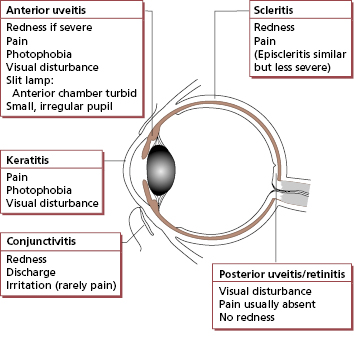

Immunological diseases of the eye fall into two groups: the eye may either be the sole target of local immunological mechanisms or it may be one of many tissues involved in a systemic process (Table 12.2). The symptoms and signs of inflammation involving different parts of the eye are summarized in Fig. 12.2 and these diseases are discussed later in the chapter.

Table 12.2 Systemic immunological diseases and the eye

| Conjunctiva | Post-infectious syndrome or arthritis urethritica (previously known as Reiter’s syndrome) |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Pemphigus/pemphigoid | |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | |

| Cornea | Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Systemic vasculitis | |

| Uveal tract and retina | Sarcoidosis |

| Spondyloarthropathies | |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | |

| Post-infectious syndrome or arthritis urethritica (previously known as Reiter’s syndrome) | |

| Psoriatic arthritis | |

| Enteropathic arthritis | |

| Systemic lupus | |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | |

| Behçet’s disease | |

| Sclera | Systemic vasculitis |

| Rheumatoid | |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) (previously known as Wegener’s syndrome) |

12.2 Conjunctivitis

Conjunctival inflammation is very common. The major causes are infection and hypersensitivity reactions (see Table 12.1).

12.2.1 Conjunctival infection

Case 12.1 emphasizes the importance of mechanical barriers in protecting the eye from infection. Failure of blinking and loss of the tear film will inevitably lead to severe infection even in the absence of any immunological defect. Bacterial infection

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree