The two most common primary malignant bone tumors, osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma, are principally diseases of childhood and adolescence, with 45% of patients younger than 16 years and 17% younger than 12 years at diagnosis.

In the last 30 years, the 5-year survival rate has increased from 10% to 70%. Even in patients with metastases at diagnosis, the 5-year survival rate has reached 20% to 30% due to chemotherapy and surgery for metastases as well as the primary tumor.11

Bone tumors in children occur predominantly in the metaphyseal region, close to the growth plate, so that sacrifice of a major physis often is necessary when the tumor is excised.

Children who have primary bone sarcoma often require chemotherapy, which may have a subsequent suppressive effect on bone growth.

Limb salvage surgery for bone tumors in the immature skeleton creates unique problems.

Maintenance of limb length after resection of one or more major growth plates

High functional and recreational demands of young patients, which require a durable reconstruction

At the knee, a constrained endoprosthesis is required (most commonly a fixed or rotating hinge implant), making it necessary for the prosthesis stem to breach the physeal plate on the side of the joint opposite to the tumor.

Reconstruction with expandable endoprostheses allows the maintenance of limb length equality, allows early weight bearing, results in predictable function, has a low risk of early complications, and is readily available.

Disadvantages include the expense of the prostheses and the complications that are expected to increase with time in surviving patients.

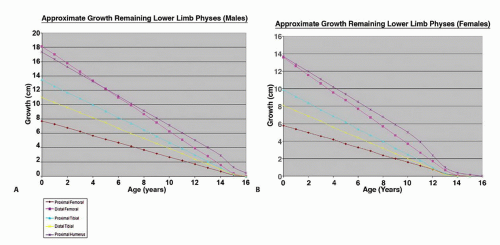

About 60% to 70% of lower limb growth occurs around the knee (distal femur and proximal tibia physes), and about 80% of total growth of the humerus occurs in the proximal physis of the humerus.

Terminal branches of the diaphyseal nutrient artery form tight loops near the physis, and the epiphysis is invaded by juxtaarticular vessels.

During childhood, the physis becomes an avascular structure that lies between two vascular beds, one epiphyseal and the other metaphyseal.

The epiphyseal vessels supply oxygen and nutrients; an intact epiphyseal vasculature is essential, therefore, to sustain the chondrocytes. The metaphyseal vessels interact with the physeal chondrocytes in the hypertrophic zone and must be intact to sustain normal ossification.10 Excessive periosteal stripping must be avoided at surgery to maintain subsequent growth.

When the estimated leg length discrepancy at skeletal maturity is more than 3 cm or when the arm length discrepancy is more than 5 cm

When the estimated arm length discrepancy at skeletal maturity is less than 5 cm, a prosthesis made up to 2 to 3 cm longer can be inserted. The operated upper limb initially is longer, but the opposite limb soon catches up.

The main problem with a slight arm length discrepancy is cosmetic.

Problems with bimanual tasks occur only when the difference is significant.

Patients whose estimated leg length discrepancy is less than 3 cm can be treated with conventional “adult-type” prostheses made longer by up to 1.5 cm, and a “sliding” prosthetic component can be used across the remaining open physis.

Girls older than 11 years or boys older than 13 years rarely require expandable prostheses because the estimated growth discrepancy after these ages is less than 3 cm (FIG 1).

Pediatric patients with suspected malignancy require the usual staging imaging studies (ie, plain radiograph and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] scan of affected bone, chest computed tomography [CT] scan, and isotope bone scan).

In addition, they require the following:

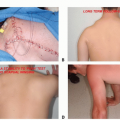

Measured full-length radiograph of the affected and contralateral limb (FIG 2)

Hand radiograph to estimate bone age based on Greulich and Pyle’s atlas6

The estimated limb length discrepancy at skeletal maturity traditionally has been estimated using the charts devised by Anderson et al2 or Pritchett et al14,15 for upper and lower extremities.

In our center, the most common sites for the use of expandable endoprostheses are the distal femur (52%), proximal tibia (24%), proximal humerus (10%), and proximal femur (6%).

Surgical techniques for excision of the sarcoma are similar to those for adult tumors, which are discussed in later chapters

(see Chaps. 9, 10, and 24,25 and 26). This chapter deals primarily with factors that must be considered with the use of expandable prostheses.

We currently use two main methods of lengthening expandable endoprostheses in our center. Their advantages and disadvantages are outlined in the following paragraphs (Table 1):

The minimally invasive expandable prosthesis has been in use since 1993. It is lengthened using a worm drive mechanism (FIG 3A,B). The mechanism is encased within the prosthesis shaft, and the telescopic implant is extended using an Allen key. The operative technique for lengthening is described later in this chapter.

The noninvasive expandable prosthesis has been in use since 2002. Surgery is not required to lengthen the prosthesis. A sealed motor unit inside the prosthesis contains a powerful magnet that can be activated by an external power source (eg, a rotating electromagnetic field). This causes the magnet to turn, and the motor works using a very-low-ratio gearing system (13061:1) to lengthen the prosthesis. The rate of lengthening is directly proportional to the length of time that the power source is applied: Lengthening of 4.6 mm takes 20 minutes (FIG 3C-E).

The physis on the opposite side of the joint can be either preserved using a sliding prosthesis or sacrificed and replaced with a fixed cemented prosthesis.

The sliding component is an uncemented, smooth component placed through a canal made centrally in the remaining preserved physis. In larger children, it is fitted inside a plastic sleeve inside the bone, which acts as a centralizer.

This sleeve allows the component to slide inside the bone as the remaining open physis grows (FIG 3F,G).

Care must be taken to minimize damage to the proximal growth plate by avoiding excessive periosteal stripping and carefully drilling out a cylindrical hole in the bone and, preferably, the center of the physis.

Insertion of the sliding component destroys no more than 13% of the growth plate in the distal femur and proximal tibia. There is no correlation between the surface area destroyed and continued growth of the physes.3,4,7

Animal models of transphyseal pediatric anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction have shown similar results.8

Table 1 Methods of Lengthening Expandable Endoprostheses

Minimally Invasive Prosthesis

JTS Noninvasive Prosthesis

Advantages

Prosthesis relatively inexpensive ($14,100)

Can have subsequent MRI scans

Reliable, with published long-term results for all sites (used since 1993)

Available in uncemented versions

Can revise easily to another expandable prosthesis without disturbing bone implant interface

No surgery required for lengthening

No risk of infection

No anesthesia risk

Reduced scarring

Painless

Outpatient procedure with reduced hospital costs

Disadvantages

Requires percutaneous operation to lengthen

Increased risk of infection

Increased anesthesia risk

Requires day case admission with increased hospital costs

Scarring with slight pain after procedure

Prosthesis is expensive ($26,500).

Cannot have subsequent MRI scans (will damage magnet of both prosthesis and MRI)

Recent advance; therefore, no long-term results available

Not available in uncemented version (forceful impaction damages motor)

Currently unable to exchange lengthening module without removing whole prosthesis (development in progress)

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree