Chapter 3 EVIDENCE-BASED CARE IN THE COMMUNITY

INTRODUCTION

The community mental health worker caring for older people will develop over time a certain pattern to their clinical work. It is likely that this pattern will have been influenced by their general professional education and training (e.g. as a nurse or social worker), by their previous experience in the workplace (e.g. in an adult mental health service) and by their exposure to the older persons’ mental health services (OPMHS) team in which they currently work. They are likely to have had professional supervision as well as direction from line managers. In addition, their OPMHS team may have clinical pathways or protocols that guide the clinical approach to older people with particular problems. Some mental health workers might even have encountered pharmaceutical company representatives seeking to promote their products. Finally, the worker is likely also to bring their patterns of behaviour to their work. These patterns have been informed by their personal experiences with the healthcare system, and those of their family and friends. So the knowledge, skills and attitudes brought by the worker to the clinical situation are likely to have been moulded over time by a variety of influences. As only some of these influences are likely to be reliable and valid sources of evidence, it is worth examining more formally the types of evidence that might inform clinical behaviour.

QUANTITATIVE VERSUS QUALITATIVE METHODS

Before considering the scientific method and the types of empirical evidence that underpin evidence-based clinical practice, it is worth outlining the differences between quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative methods involve the collection of observations using numbers. For example, change in the average score on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale is commonly used to establish the extent of improvement in older people with major depressive disorder in clinical trials of new psychological or pharmacological treatments. By contrast, qualitative methods involve the collection of observations without using numbers. For example, a focus group might be used to find out which aspects of a respite care service are most helpful to the carers of people with dementia. In clinical research, qualitative data are sometimes used to complement quantitative data.

TYPES OF EVIDENCE

Scientific approaches to clinical evidence include peer-reviewed case studies, case series, case-control studies, cohort studies, randomised controlled trials, secondary analyses, systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Each of these will now be briefly outlined.

Cohort study

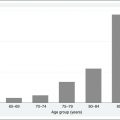

Cohort studies are observational studies that employ a longitudinal perspective. They lend themselves to causal thinking. In the typical cohort study, a population sample (the cohort) is followed over time (often years) to see what happens to them. For instance, a cohort study might be used to investigate predictors of depression as people grow older. Information on potential predictors is obtained at baseline, and so is not confounded by knowledge of which participants will ultimately develop depression. The main limitations of cohort studies are the length of time they take to run and the associated expense of mounting them, the difficulty of keeping the cohort intact during a lengthy period of follow-up (people move house, get fed up with the study, or die), and the problem of trying to predict at the beginning of the study which potential predictor variables are likely to be relevant.

Randomised controlled trials

Because of the critical importance of RCTs, most medical journals now require the authors of papers describing the results of RCTs to have registered their RCT on a public access website prior to any people being recruited to the study. The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) clinical trials website (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry website (www.anzctr.org.au) record information about all clinical trials regardless of whether they involve pharmaceutical agents or non-pharmacological interventions such as CBT. Scientific journals that publish the findings from clinical trials usually now require researchers to describe their research according to the CONSORT guidelines (Altman et al 2001).

Measures of statistical and clinical significance

Another metric that is useful in human clinical trials is the ‘number needed to treat’ (NNT). The NNT can be defined as the number of people who need to be treated with an intervention for one person to respond who would not have responded to a placebo. Treatments with better efficacy have smaller NNTs. A related concept is the number needed to harm (NNH).

Measures of statistical significance often provide little information about the likely clinical significance of research findings. For this, we need to use a different approach. In determining clinical significance it is useful to have data also from normal people—so-called normative data. If a research finding is statistically significant and the intervention brings people with a particular clinical condition (e.g. a major depressive episode) back into the normal range on a clinical scale (e.g. the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale), then the findings are likely also to be clinically significant. Thus, moving a person from a pathological score to a normal score on a scale might suggest clinical significance. Paradoxically, statistical approaches have also been taken to estimate the clinical significance of change scores using a metric called the Reliable Change Index (RCI) (Jacobson & Truax 1991). Alternatively, if a person satisfies diagnostic criteria (e.g. DSM–IV or ICD–10) for a major depressive episode before the intervention and does not meet these criteria after the intervention, it could be argued that they have achieved clinically significant change in their diagnostic status.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree