Evaluating the Geriatric Patient: Introduction

Comprehensive evaluation of an older individual’s health status is one of the most challenging aspects of clinical geriatrics. It requires sensitivity to the concerns of people, awareness of the many unique aspects of their medical problems, ability to interact effectively with a variety of health professionals, and often a great deal of patience. Most importantly, it requires a perspective different from that used in the evaluation of younger individuals. Not only are the a priori probabilities of diagnoses different, but one must be attuned to more subtle findings. Progress may be measured on a finer scale. Special tools are needed to ascertain relatively small improvements in chronic conditions and overall function compared with the more dramatic cures of acute illnesses often possible in younger patients. Creativity is essential to incorporate these tools efficiently in a busy clinical practice.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment has been shown to improve both mortality and the chances of remaining in the community (Barer, 2011; Ellis et al., 2011). The challenge is to use it efficiently. Complex patients and those facing major long-term care decisions are strong candidates, but studies have also shown benefit for persons presumably at low risk. As described in Chapter 4, home visits to basically well older persons can prevent nursing home admissions and functional decline.

The purpose of the evaluation and the setting in which it takes place will determine its focus and extent. Considerations important in admitting a geriatric patient with a fractured hip and pneumonia to an acute care hospital during the middle of the night are obviously different from those in the evaluation of an older demented patient exhibiting disruptive behavior in a nursing home. Elements included in screening for treatable conditions in an ambulatory clinic are different from those in assessment of older individuals in their own homes or in long-term care facilities.

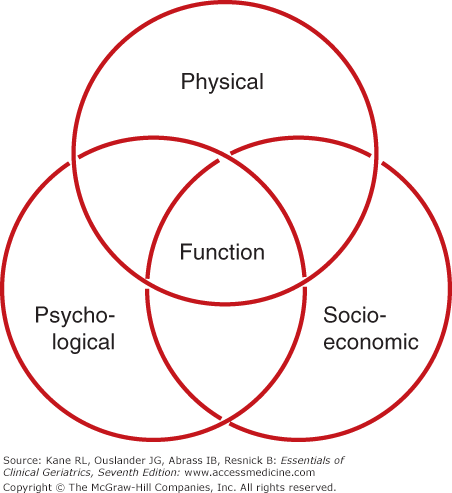

Despite the differences dictated by the purpose and setting of the evaluation, several essential aspects of evaluating older patients are common to all purposes and settings. Figure 3-1 depicts these aspects. Several comments on addressing them are in order:

Physical, psychological, and socioeconomic factors interact in complex ways to influence the health and functional status of the geriatric population.

Comprehensive evaluation of an older individual’s health status requires an assessment of each of these domains. The coordinated efforts of several different health-care professionals functioning as an interdisciplinary team are needed.

Functional abilities should be a central focus of the comprehensive evaluation of geriatric patients. Other more traditional measures of health status (such as diagnoses and physical and laboratory findings) are useful in dealing with underlying etiologies and detecting treatable conditions, but in the geriatric population, measures of function are often essential in determining overall health, well-being, and the need for health and social services.

Just as function is the common language of geriatrics, assessment lies at the heart of its practice. Special techniques that address multiple problems and their functional consequences offer a way to structure the approach to complicated geriatric patients. The core of geriatric practice has been considered the comprehensive geriatric assessment, but its role has been actively debated. Geriatric assessment has been tested in a variety of forms. Table 3–1 summarizes the findings from a number of randomized controlled trials of different approaches to geriatric assessment. Annual in-home comprehensive geriatric assessment as a preventive strategy demonstrated the potential to delay the development of disability and reduce permanent nursing home stays (Stuck et al., 2002). Controlled trials of approaches to hospitalized geriatric patients suggest comprehensive geriatric assessment by a consultation team with limited follow-up does not improve health or survival of selected geriatric patients (Reuben et al., 1995) but suggests that a special acute geriatric unit can improve function and reduce discharges to institutional care (Landefeld et al., 1995). A controlled multisite Veterans Affairs trial of inpatient geriatric evaluation and management demonstrated significant reductions in functional decline without increased costs (Cohen et al., 2002). Results of outpatient geriatric assessment have been mixed and less compelling (Cohen et al., 2002). However, a randomized trial of outpatient geriatric assessment showed that it prevented functional decline (Reuben et al., 1999).

Setting | Examples of assessment strategies | Selected outcomes* |

|---|---|---|

Community/outpatients | Social worker assessment and referral Nursing assessment and referral Annual in-home assessment by nurse practitioner Multidisciplinary clinic assessment | Reduced mortality Reduced hospital use Reduced permanent nursing home use Delayed development of disability |

Hospital inpatient (specialized units) | Interdisciplinary teams with focus on function, geriatric syndromes, rehabilitation | Reduced mortality Improved function Reduced acute hospital and nursing home use |

Hospital inpatient consultation | Geriatric consultation teams | Mixed results Some studies show improved function and lower shortterm mortality Other studies show no effects |

There is considerable variation in approaches to the comprehensive assessment of geriatric patients. Various screening and targeting strategies have been used to identify appropriate patients for more comprehensive assessment. These strategies range from selection based on age to targeting patients with a certain number of impairments or specific conditions. Sites of assessment vary as well and include the clinic, the home, the hospital, and different levels of long-term care. Geriatric assessment also varies in terms of which discipline carries out the different components of the assessment as well as in the specific assessment tools used. Despite the dramatic variation in approach to targeting, personnel used, and measures employed, a clear pattern of effectiveness has emerged. Taken together, these results are both heartening and cautioning. Systematic approaches to patient care are obviously desirable. The issue is more how formalized these assessments should be. Research suggests that the specifics of the assessment process seem to be less important than the very act of systematically approaching older people with the belief that improvement is possible.

A major concern about such assessments is efficiency. Because of the multidimensional nature of geriatric patients’ problems and the frequent presence of multiple interacting medical conditions, comprehensive evaluation of the geriatric patient can be time consuming and thus costly. It is important to reduce duplication of effort. It is possible to have interprofessional collaboration in determining what data should be collected, but the actual data collection is best delegated to one or, at most, a few team members. Additional expertise can be brought to bear if the initial screening uncovers an area that requires it. Another crucial lesson is that assessment without follow-up is unlikely to make any difference. Thus, the term “geriatric assessment” has given way to the concept of geriatric evaluation and management. There must be strong commitment to act on the problems uncovered and to follow up long enough to be sure that they have responded to the treatment prescribed.

The development of a close-knit interdisciplinary team with minimal redundancy in the assessments performed.

Use of carefully designed questionnaires that reliable patients and/or caregivers can complete before an appointment.

Incorporation of screening tools that target the need for further, more in-depth assessment.

Use of assessment forms that can be readily incorporated into a computerized relational database.

Integration of the evaluation process with case management activities that target services based on the results of the assessment.

This chapter focuses on the general aspects of assessing geriatric patients; sections on geriatric consultation, preoperative evaluation, and environmental assessments are included in the chapter.

History

Sir William Osler’s aphorism, “Listen to the patient, he’ll give you the diagnosis,” is as true in older patients as it is in younger patients. In the geriatric population, however, several factors make taking histories more challenging, difficult, and time consuming.

Table 3–2 lists difficulties commonly encountered in taking histories from geriatric patients, the factors involved, and some suggestions for overcoming these difficulties. Impaired hearing and vision (despite corrective devices) are common and can interfere with effective communication.

Difficulty | Factors involved | Suggestions |

|---|---|---|

Communication | Diminished vision | Use well-lit room |

Diminshed hearing | Eliminate extraneous noise Speak slowly in a deep tone Face patient, allowing patient to see your lips Use simple amplification device for severely hearing impaired | |

Slowed psychomotor performance | If necessary, write questions in large print Leave enough time for the patient to answer | |

Underreporting of symptoms | Health beliefs Fear Depression Altered physical and physiological responses to disease process Cognitive impairment | Ask specific questions about potentially important symptoms (see Table 3–3) Use other sources of information (relatives, friends, other caregivers) to complete the history |

Vague or nonspecific symptoms | Altered physical and physiological responses to disease process Altered presentation of specifc diseases Cognitive impairment | Evaluate for treatable diseases, even if the symptoms (or signs) are not typical or specific when there has been a rapid change in function Use other sources of information to complete history |

Multiple complaints | Prevalence of multiple coexisting diseases Somatization of emotions—”masked depression” (see Chap. 7) | Attend to all somatic symptoms, ruling out treatable conditions Get to know the patient’s complaints; pay special attention to new or changing symptoms Interview the patient on several occasions to complete the history |

Techniques such as eliminating extraneous noises, speaking slowly and in deep tones while facing the patient, and providing adequate lighting can be helpful. The use of simple, inexpensive amplification devices with earphones can be especially effective, even among the severely hearing impaired. Patience is truly a virtue in obtaining a history; because thought and verbal processes are often slower in older than in younger individuals, patients should be allowed adequate time to answer in order not to miss potentially important information. At the same time, the cardinal rule of open-ended questions may need to be tempered to get the maximum amount of information in the time allocated.

Many older individuals underreport potentially important symptoms because of their cultural and educational backgrounds as well as their expectations of illness as a normal concomitant of aging. More aggressive probing may be necessary. Fear of illness and disability or depression accompanied by a lack of self-concern may also cause less frequent reporting of symptoms. Altered physical and physiological responses to disease processes (see Chapter 1) can result in the absence of symptoms (such as painless myocardial infarction or ulcer and pneumonia without cough). Symptoms of many diseases can be vague and nonspecific because of these age-related changes. Impairments of memory and other cognitive functions can result in an imprecise or inadequate history and compound these difficulties. Asking specifically about potentially important symptoms (such as those listed in Table 3–3) and using other sources of information (such as relatives, friends, and other caregivers) can be very helpful in collecting more precise and useful information in these situations.

Social history | |

Living arrangements Relationships with family and friends Expectations of family or other caregivers Economic status Abilities to perform activities of daily living (see Table 3–8) Social activities and hobbies Mode of transportation Advance directives (see Chap. 17) | |

Past medical history | |

Previous surgical procedures Major illnesses and hospitalizations Previous transfusions Immunization status Influenza, pneumococcus, tetanus, zoster Preventive health measures Mammography Papanicolaou (Pap) smear Flexible sigmoidoscopy Antimicrobial prophylaxis Estrogen replacement Tuberculosis history and testing Medications (use the “brown bag” technique; see text) Previous allergies Knowledge of current medication regimen Compliance Perceived beneficial or adverse drug effects | |

| Systems review | |

Ask questions about general symptoms that may indicate treatable underlying disease such as fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, insomnia, recent change in functional status Attempt to elicit key symptoms in each organ system, including the following: | |

| System | Key symptoms |

| Respiratory | Increasing dyspnea Persistent cough |

| Cardiovascular | Orthopnea Edema Angina Claudication Palpitations Dizziness Syncope |

Gastrointestinal | Difficulty chewing Dysphagia Abdominal pain Change in bowel habit |

Genitourinary | Frequency Urgency Nocturia Hesitancy, intermittent stream, straining to void Incontinence Hematuria Vaginal bleeding |

Musculoskeletal | Focal or diffuse pain Focal or diffuse weakness |

Neurological | Visual disturbances (transient or progressive) Progressive hearing loss Unsteadiness and/or falls Transient focal symptoms |

Psychological | Depression Anxiety and/or agitation Paranoia Forgetfulness and/or confusion |

At the other end of the spectrum, geriatric patients with multiple complaints can frustrate the health-care professional who is trying to sort them all out. The multiplicity of complaints can relate to the prevalence of coexisting chronic and acute conditions in many geriatric patients. These complaints may, however, be deceiving. Somatic symptoms may be manifestations of underlying emotional distress rather than symptoms of a physical illness, and symptoms of physical conditions may be exaggerated by emotional distress (see Chapter 5). Getting to know patients and their complaints and paying particular attention to new or changing symptoms are helpful in detecting potentially treatable conditions.

Clinicians may become impatient with the slow pace of older patients and their tendency to wander from the subject at hand. In desperation, they shift their focus to the accompanying family members who can provide a more lucid and linear history. But this tendency to bypass the older patient can have several serious effects. Not only does it diminish the self-image of the older patient and reinforce a message of dependency, it may miss important information that the patient knows but the family member does not.

Table 3–3 lists aspects of the history that are especially important in geriatric patients. It is often not feasible to gather all information in one session; shorter interviews in a few separate sessions may prove more effective in gathering these data from some geriatric patients.

Some topics that may be especially important to an older person’s quality of life are often skipped over because they are embarrassing to the clinician or the patient. Issues like fecal and urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction can be important areas to explore. Given its prevalence, vulnerability to treatment, and ability to complicate the care of other conditions, it is important to screen for depression. Chapter 7 reviews the measures available for depression screening in older patients.

Often shortchanged in medical evaluations, the social history is a critical component. Understanding the patient’s socioeconomic environment and ability to function within it is crucial in determining the potential impact of an illness on an individual’s overall health and need for health services. Especially important is the assessment of the family’s feelings and expectations. Many family caregivers of frail geriatric patients have feelings of both anger (at having to care for a dependent family member) and guilt (over not being able or willing to do enough) and have unrealistic expectations. Such unrealistic expectations are often based on a lack of information and can interfere with care if not discussed. Unlike younger patients, older patients often have had multiple prior illnesses. Therefore, the past medical history is important in putting the patient’s current problems in perspective; this can also be diagnostically important. For example, vomiting in an elderly patient who has had previous intra-abdominal surgery should raise the suspicion of intestinal obstruction from adhesions; nonspecific constitutional symptoms (such as fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss) in a patient with a history of depression should prompt consideration of a relapse. Because older individuals are often treated with multiple medications, they are at increased risk of noncompliance and adverse effects (see Chapter 14). A detailed medication history (including both prescribed and over-the-counter drugs) is essential.

The brown bag technique is very helpful in this regard; have the patient or caregiver empty the patient’s medicine cabinet (prescribed and over-the-counter drugs as well as nontraditional remedies) into a brown paper bag and bring it to each visit. More often than not, one or more of these medications can, at least in theory, contribute to geriatric patients’ symptoms. Clinicians should not hesitate to turn to pharmacists for help in determining potential drug interactions.

A complete systems review, focusing on potentially important and prevalent symptoms in the elderly, can help overcome many of the difficulties described earlier. Although not intended to be all-inclusive, Table 3–3 lists several of these symptoms.

General symptoms can be especially difficult to interpret. Fatigue can result from a number of common conditions such as depression, congestive heart failure, anemia, and hypothyroidism. Anorexia and weight loss can be symptoms of an underlying malignancy, depression, or poorly fitting dentures and diminished taste sensation. Age-related changes in sleep patterns, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux, congestive heart failure with orthopnea, or nocturia can underlie complaints of insomnia. Because many frail geriatric patients limit their activity, some important symptoms may be missed. For example, such patients may deny angina and dyspnea but restrict their activity to avoid the symptoms. Questions such as “How far do you walk in a typical day?” and “What is the most common activity you carry out in a typical day?” can be helpful in patients suspected of limiting their activities to avoid certain symptoms.

Physical Examination

The common occurrence of multiple pathologic physical findings superimposed on age-related physical changes complicates interpretation of the physical examination. Table 3–4 lists common physical findings and their potential significance in the geriatric population.

Physical findings | Potential significance |

|---|---|

Vital signs | |

Elevated blood pressure | Increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity; therapy should be considered if repeated measurements are high (see Chap. 11) |

Postural changes in blood pressure | May be asymptomatic and occur in the absence of volume depletion Aging changes, deconditioning, and drugs may play a role Can be exaggerated after meals Can be worsened and become symptomatic with antihypertensive, vasodilator, and tricyclic antidepressant therapy |

Irregular pulse | Arrhythmias are relatively common in otherwise asymptomatic elderly; seldom need specific evaluation or treatment (see Chap. 11) |

Tachypnea | Baseline rate should be accurately recorded to help assess future complaints (such as dyspnea) or conditions (such as pneumonia or heart failure) |

Weight changes | Weight gain should prompt search for edema or ascites Gradual loss of small amounts of weight common; losses in excess of 5% of usual body weight over 12 months or less should prompt search of underlying disease |

General appearance and behavior | |

Poor personal grooming and hygiene (eg, poorly shaven, unkempt hair, soiled clothing) | Can be signs of poor overall function, caregiver’s neglect, and/or depression; often indicates a need for intervention |

Slow thought processes and speech | Usually represents an aging change; Parkinson disease and depression can also cause these signs |

Ulcerations | Lower extremity vascular and neuropathic ulcers common Pressure ulcers common and easily overlooked in immobile patients |

Diminished turgor | Often results from atrophy of subcutaneous tissues rather than volume depletion; when dehydration suspected, skin turgor over chest and abdomen most reliable |

Ears (see Chap. 13) | |

Diminished hearing | High-frequency hearing loss common; patients with difficulty hearing normal conversation or a whispered phrase next to the ear should be evaluated further Portable audioscopes can be helpful in screening for impairment |

Eyes (see Chap. 13) | |

Decreased visual acuity (often despite corrective lenses) | May have multiple causes, all patients should have thorough optometric or ophthalmologic examination Hemianopsia is easily overlooked and can usually be ruled out by simple confrontation testing |

Cataracts and other abnormalities | Fundoscopic examination often difficult and limited; if retinal pathology suspected, thorough ophthalmologic examination necessary |

Mouth | |

Missing teeth | Dentures often present; they should be removed to check for evidence of poor fit and other pathology in oral cavity Area under the tongue is a common site for early malignancies |

Skin | |

Multiple lesions | Actinic keratoses and basal cell carcinomas common; most other lesions benign |

Chest | |

Abnormal lung sounds | Crackles can be heard in the absence of pulmonary disease and heart failure; often indicate atelectasis |

Cardiovascular (see Chap. 11) | |

Irregular rhythms | See Vital Signs at the beginning of the table |

Systolic murmurs | Common and most often benign; clinical history and bedside maneuvers can help to differentiate those needing further evaluation Carotid bruits may need further evaluation |

Vascular bruits | Femoral bruits often present in patients with symptomatic peripheral vascular disease |

Diminished distal pulses | Presence or absence should be recorded as this information may be diagnostically useful at a later time (eg, if symptoms of claudication or an embolism develop) |

Abdomen | |

Prominent aortic pulsation | Suspected abdominal aneurysms should be evaluated by ultrasound |

Genitourinary (see Chap. 8) | |

Atrophy | Testicular atrophy normal; atrophic vaginal tissue may cause symptoms (such as dyspareunia and dysuria) and treatment may be beneficial |

Pelvic prolapse (cystocele, rectocele) Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |