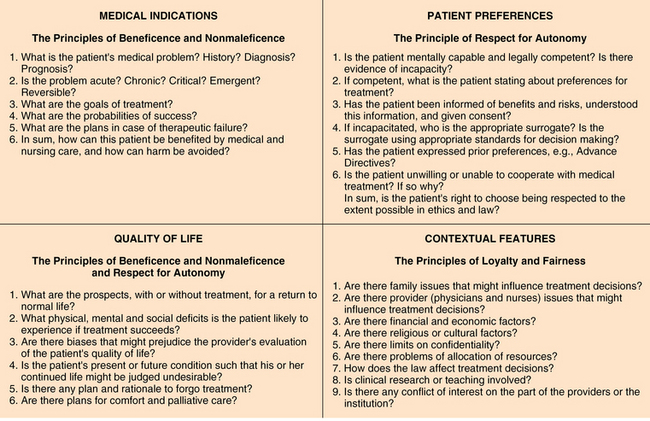

7 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Discuss the most commonly cited principles of ethical decision making in medical care. • Understand how to systematically elucidate and resolve ethical dilemmas. • Discuss the requirements of informed consent and the criteria for decisional capacity. • Discuss the role and use of different types of advance directives, including do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders. • Understand the use of the term futility as it applies to medical decision making. • Discuss ethical concerns regarding assisted suicide and what’s known as the double effect. • Discuss the unique issues involving provision of food and fluid. Ethics is the field that systematically studies morality, which is defined as the rightness and wrongness of human acts. Medical ethics is the discipline that studies morality in health care, generally using a process that attempts to recognize and seek solutions to moral questions or dilemmas that arise in the care and treatment of patients. As a branch of moral philosophy, medical ethics is responsive to shifts in philosophical opinion and fashion. It is also a field that is a fusion of theory and practice.1 Moral dilemmas arise when the rights and wishes of patients conflict with the obligations of clinicians or when there are competing obligations among clinicians. These rights and obligations may be informed by philosophic, cultural, religious, or personal principles, beliefs, and values. In geriatric medicine, rights and obligations are often influenced and complicated by factors such as limited life expectancy, cognitive impairment, impaired decision-making capacity, insufficient social and economic resources, and the complexity of multiple concomitant medical problems and functional disorders.2 Traditional principles of medical ethics derived largely from the works of Greek philosophers such as Hippocrates3 and Pythagorus.4 During the second half of the twentieth century, increasing pressure on the medical establishment from technological change, cultural upheaval, and the increasing complexity of medical care and the issues it raised resulted in the need to more explicitly frame the principles of medical ethics. Although there are a number of alternative theories of medical ethics—such as the virtue-based theories favored by the Greek philosophers, the ethics of caring,5 and casuistry6—there remain four prima facie principles that are most often cited as the bedrock of clinical ethics. These are autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice.7 The principle of autonomy refers to the duty to respect a patient’s right to self-determination. This has been legally enshrined in the judicial ruling of Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital (NY 1914), in which Justice Cardozo found that, “Every human being of adult years and of sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his body.”8 Integral to the principle of autonomy is the right to receive sufficient factual information to allow self-determination. This is the basis of informed consent, established in the Nuremberg code, which states, “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.”9 In Nathanson v. Kline (KS 1960), a case that centered on the failure to inform a patient of potential surgical risks, the ruling found that, “It follows that each man is considered to be master of his own body, and he may, if he be of sound mind, prohibit the performance of life-saving surgery or other medical treatment.”10 In addition to establishing the right of an autonomous patient to refuse treatment, these rulings also introduce the “of sound mind” concept, which is indicative of a patient’s capacity to understand what has been explained, appreciate the situation and its consequences, rationally manipulate information, and communicate choices.11 Decision-making capacity is a critical requirement for providing informed consent and, therefore, for exercising autonomy. Truth-telling is an essential component of the exercise of autonomy. The recognition that there is an obligation to provide truthful information to patients about potentially life-threatening conditions is a relatively recent phenomenon. A 1961 survey of physicians in the United States reported that 90% would not reveal a diagnosis of cancer to their patients.12 A 1979 survey reported that 97% of physicians would reveal a diagnosis of cancer to their patients.13 A recent survey of hospitalized patients reported that a large majority would prefer to be told of a diagnosis of cancer or Alzheimer’s disease. Among those who were unsure or who did not want to be told, a majority would want to be told if it was essential to treatment. Preferences did not differ by age.14 Age is not, by itself, an obstacle to the full exercise of autonomy. In one study, even very old hospitalized patients were able to express their health values, underscoring the need to elicit such choices directly from the patient, unless that patient lacks decision-making capacity.15 Justice refers to the duty to treat patients fairly. Justice can be viewed along two dimensions: access and allocation.16 Access refers to whether those who are entitled to health care resources can obtain them. Allocation refers to the determination of how resources are distributed. The distribution of rights and responsibilities among the members of a society in a manner governed by consistent moral norms is often referred to as distributive justice. The principle of justice can apply to either the macroenvironment, such as the decisions made to ration health care within Oregon’s Medicaid program,17 or the microenvironment, such as decisions made to allocate money and other resources within a hospital, nursing home, or office practice. In a hospital or nursing home, conflicts involving the principle of justice may revolve around the use of scarce, expensive, or labor-intensive medical interventions in frail, elderly patients with limited life expectancies. On a national scale, justice may be the central principle in determining whether Medicare should cover a particular procedure or in determining who should have control over allocation decisions in managed care organizations.18 In addition to the principles outlined in the previous sections, there are other ethical principles that are common in geriatrics, particularly in communal settings such as assisted-living facilities or nursing homes, in which elderly residents not only obtain medical care but consider the facility their home. The principle of community, which refers to the duty to balance individual need with communal need, takes on great importance in such settings. Not only is personal autonomy important, but also individual dignity, a closely related but distinct value, is greatly valued. Also closely related to autonomy, the principle of authenticity refers to the ability to choose a lifestyle consistent with one’s own values, beliefs, and habits.19 These ethical principles largely underlie the advocacy of culture change in the nursing home industry. The culture change movement has as its goals to provide residents more homelike environments and choice over their lives, and to provide staff members the authority and empowerment to facilitate those choices.20,21 There are several models for systematically evaluating and analyzing dilemmas in medical ethics. One of the most commonly used models is the “four topics” model devised by Jonsen et al.22 This is a case-based approach that allows an organized review of the facts and issues in a given case, according to four topics: medical indications, patient preferences, quality of life, and contextual features (Figure 7-1). Figure 7-1 Four topics for ethical analysis. (From Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical ethics: A practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002.) Once the facts of the case are organized, it is important to identify the ethical dilemma(s), if any. Only when the ethical questions are framed is it possible to formulate potential solutions. Frequently, ethical dilemmas have more than one morally permissible alternative. If the ethics consultant or ethics committee has been asked to participate, it may be their role to outline these alternatives. Nonetheless, it generally falls to the health care team and patient to determine which alternative will be followed. What appears at first to be an ethical dilemma may ultimately emerge as an interpersonal dispute among family members or between staff and family members.23 In geriatrics, patients may have several family members, usually children, who may disagree with each other or with the health care team over decisions, large and small, sometimes making medical management time-consuming and difficult. In these cases, typical ethical deliberation may not always be useful or sufficient. Alternate techniques such as mediation,24 negotiation,25 or a combination of these and other methods of conflict resolution may be necessary. Informed consent is the foundation for the exercise of autonomy. It has become increasingly central to both the ethical and legal regulation of American medicine and the clinician–patient relationship since the concept was first used in 1957.26 Informed consent is more than simply the required signing of permission forms before surgery or other medical procedures. In representing the means by which the principles of autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence are balanced and incorporated into medical decision making,27 informed consent requires disclosure and comprehension of information as well as voluntary and competent decision making28 (Box 7-1). The requirement for disclosure is not an obligation for the clinician to impart everything about a proposed intervention to the patient. Some states measure the adequacy of disclosure according to the standard determined by what a reasonable clinician would disclose, whereas others measure adequacy by what information a reasonable patient would need to make the decision.29 Although this may appear at first glance to be vague, “reasonable” generally means that disclosure should provide information about the goals of the procedure, the probability of success, and the most probable adverse effects. In addition, disclosure should include information about alternative options, including foregoing of any procedure. When patients are sick, they are often vulnerable as well. There may be conflicting values, not only among the patient’s own values but also among the patient’s, family’s, and other caregivers’ values. It is important, therefore, that the clinician ascertain that the decision is not coerced, that it truly represents the free will of the patient. The clinician may also exert undue pressure on the patient, interfering with the patient’s perceived ability to express his or her free will. A patient may be afraid of disappointing the clinician or, worse, of being abandoned by the clinician if he or she does not consent. In some instances, perception by the patient of abandonment may not mean the complete exit of the clinician from the clinician–patient relationship but the fear that the clinician may not be fully committed to all the patient’s needs should the patient choose to pursue a course contrary to the clinician’s recommendation.30 Therefore, part of the disclosure process should include information regarding the management of the patient and an assurance of support should he or she refuse the proposed intervention. In geriatric medicine, the prevalence of cognitive impairment owing to dementia or delirium raises difficult questions about the patient’s capacity to participate in the process of informed consent. It is important to distinguish between cognitive impairment and impaired decision-making capacity. The presence of cognitive impairment does not necessarily rule out the ability to render all medical decisions, nor is an abnormal Folstein mini-mental state score,31 by itself, an indication of incapacity.32 The determination of capacity should ideally be made on a case-by-case basis as part of the process of obtaining informed consent. A patient, who, because of dementia, is unable to participate in rendering a decision about a lower extremity vascular procedure, may nevertheless be able to clearly express a decision about resuscitation. Thus the inability to provide informed consent for one intervention should not necessarily imply a presumption of incapacity for other interventions. Likewise, the presence of mental illness, such as depression, should not lead to the conclusion that the patient cannot participate in decision making,33 although there is evidence that the judgment of acutely ill adults may be sufficiently impaired in many cases to interfere with decision making.34 This underscores the importance of using a systematic assessment of decision making specific to the decision at hand. The set of standards that has evolved for assessing decision-making capacity includes the following components: (1) understanding of information that is disclosed in the informed consent process, (2) appreciation of the information for one’s own circumstances, (3) reasoning with the information, and (4) expressing a choice35,36 (Box 7-2).

Ethics

Principles of medical ethics

Autonomy

Justice

Other principles

Structure for deliberating ethical dilemmas

Informed consent

Disclosure

Voluntariness

Capacity

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ethics