Fig. 6.1

Kaplan-Meier Curve comparing patients (with ischemic heart disease or ≥2 comorbidities) choosing dialysis option versus conservative management (Source: Murtagh et al. [15]; Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE. Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007

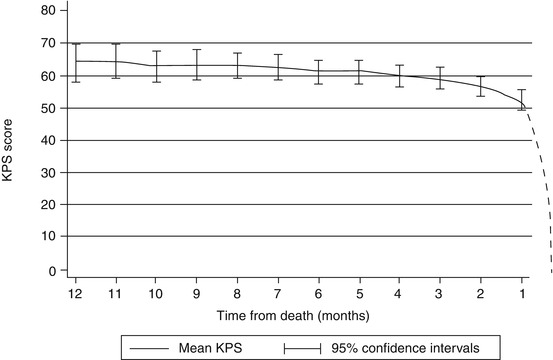

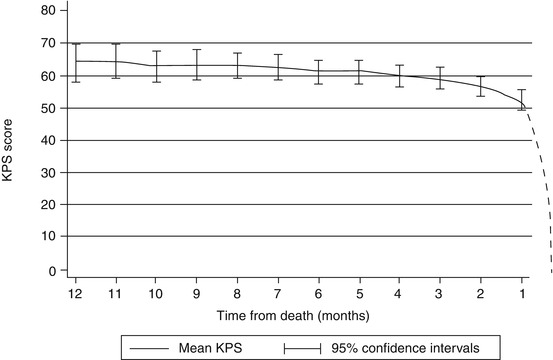

Patients receiving conservative management are often able to maintain their functionality and quality of life for the majority of their remaining duration of life, until experiencing a sharp functional decline within the last month of their life. This was demonstrated in a study using the Karnofsky performance scale, a well-established ten-point scale used to assess functional status with an emphasis on physical performance and dependency, in which functional status was maintained at a moderate level in individuals with ESRD receiving conservative management until late in the course of illness (Fig. 6.2) [33]. In contrast, elderly patients who are initiated on renal replacement therapy often start experiencing a deterioration in functionality soon after going on dialysis that progresses until their eventual demise. As stated earlier, patients with significant comorbid disease who are managed conservatively are also more likely to pass away at home or in hospice and spend fewer days institutionalized than their dialysis-receiving counterparts. Patients on dialysis often spend more time in hospitals due to the many complications associated with dialysis [16]. For instance, the rapid fluid shifts which occur with dialysis often cause derangements in physiology leading to hypotension with subsequent complications of ischemia such as angina and stroke. It is important to determine which of the treatment modalities for ESRD, renal replacement versus conservative, are most consistent with each patient’s medical goals. In cases where patients value quality of life and spending more time at home instead of enduring frequent hospital visits and interventions, conservative management is the appropriate option [30].

Fig. 6.2

The trajectory of decline in conservatively managed stage 5 CKD patients in the last year of life. KPS Karnofsky performance scale (Source: Murtagh et al. [33]; Originally from Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall JM, Higginson IJ. End-stage renal disease: a new trajectory of functional decline in the last year of life. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2011)

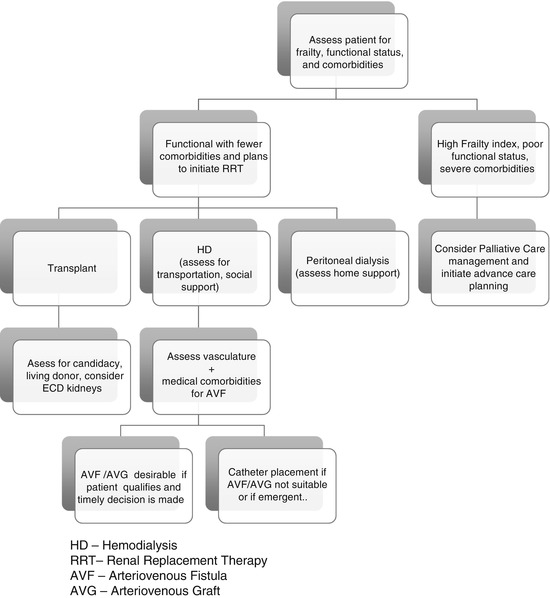

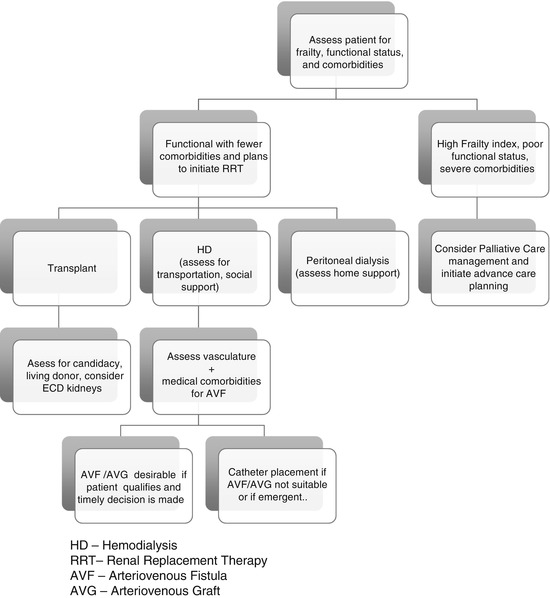

Fig. 6.3

Treatment options for elderly patient diagnosed with end-stage renal disease. HD hemodialysis, RRT renal replacement therapy, AVF arteriovenous fistula, AVG arteriovenous graft

The Importance of Advance Care Planning

It is imperative for the nephrologist and other members of the renal care team to facilitate advance care planning early in the course of renal disease, when patients are most capable of making clear decisions regarding their end-of-life care [11]. Advance care planning is a means to assist the patient in understanding their current medical condition and prognosis, to help the renal care team understand the patient/family’s wishes and goals, and to plan ahead for scenarios that may occur in the future as the disease progresses. Advance care planning is based on the ethical principle of respect for “self-determination”/patient autonomy and is a series of patient-centered discussions that focus on each individual patient’s wishes and treatment preferences as related to their medical situation and prognosis [34]. These discussions should include creating advance directives that can help guide decision-making to best meet the patient’s needs in the future. In addition, discussing the anticipated trajectory of care in advance will also help ensure the patient receives care consistent with his/her goals should an acute situation arise that demands prompt decision-making [30]. Similar to other elders or any patient with a significant illness, the patient should designate a single person to be their surrogate decision-maker (i.e., health-care proxy, medical power of attorney). This individual should be someone who understands the patient’s wishes/goals and can make decisions on behalf of the patient if the patient loses capacity [32]. It is important to recognize that advance care planning is a very dynamic process [30]. As the patient’s illness progresses, these discussions should be revisited again and again to continually clarify goals and establish tenets of care as the patient/family’s views may change over time.

Conclusion

While renal replacement therapy has the ability to extend biological life, it often results in reduced quality of life and, therefore, may not be medically indicated or aligned with a patient’s goals. This highlights the importance for open, honest communication between the patient/family and members of the renal care team regarding management options for ESRD as related to the patient’s medical wishes. The issue of ESRD care ultimately becomes a process of shared decision-making where the physician and renal care team members, along with a well-informed patient/family, are able to understand each other’s positions and mutually establish an appropriate treatment plan. This may or may not involve dialysis, as it depends on the patient’s medical prognosis and personal values. Regardless of the specific treatment chosen, the most important aspect in choosing a management plan is ensuring it is patient centered and grounded on the ethical principles of respect for the patient’s/family’s goals and values while upholding the principles of beneficence, non-maleficence, and professional integrity.

Clinical Pearls

- 1.

Concurrent comorbidities, including frailty, falls, functional status, and cognitive impairment, should be carefully considered when deciding between renal replacement therapy and medical management of ESRD.

- 2.

In elders with multiple comorbidities, conservative management is often an acceptable alternative to renal replacement therapy.

- 3.

Elders in whom CKD is managed conservatively are more likely to die at home or in hospice and spend fewer days institutionalized compared to those receiving renal replacement therapy.

- 4.

Advanced care planning should ideally begin early in the course of renal disease so patients can actively participate in conversations regarding their goals of care and work with their providers to determine how these can best be achieved.

References

1.

United States Renal Data System. 2015 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, 2015. (a) The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government.

2.

Xue QL. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(1):1–15. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.009.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

3.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–57. doi:10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146.CrossRefPubMed

4.

Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(11):2960–7. ASN.2007020221 [pii].CrossRefPubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree