Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB) is a rare malignancy, representing only 3% to 6% of all sinonasal malignancies. A wide array of treatment options for ENB have been described in the literature, but prospective clinical trials are absent given the tumor’s rarity and natural history. Delay in diagnosis leading to an initial advanced stage of presentation is common secondary to the clinically hidden primary site at the anterior skull base. This article presents data from the current body of literature and reviews the advocated roles for surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Key Points

- •

For selected presentations, endoscopy-assisted craniofacial resections and “endoscopic-only” resections have demonstrated success with long-term results comparable to those of conventional open craniofacial resection techniques.

- •

Most series advocate combined modality therapy (surgery and radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy) in the management of esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB).

- •

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been advocated for locally invasive and advanced staged ENBs and has demonstrated the capacity to significantly decrease gross tumor volume before definitive surgery and/or radiation.

- •

Elective management of the neck in patients with ENB remains a controversial topic. Early surgical salvage of patients with regional recurrence is possible in a portion of patients.

- •

ENB requires long-term follow-up (>10 years) given the extended time to local and regional recurrence.

Introduction

Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB), also known as olfactory neuroblastoma, is an uncommon malignancy of the head and neck, representing only 3% to 6% of nasal cavity and sinonasal neoplasms. First described by Berger, Luc, and Richard in 1924, ENB is a tumor of neural crest origin that is considered to arise from the olfactory neuroepithelium of the olfactory cleft in the superior nasal cavity at the anterior skull base. Local spread of tumor can extend throughout the paranasal sinuses and skull base with invasion of the orbit, cavernous sinus, and brain.

Several treatment approaches for ENB have been described in the literature, but rigorous, prospective treatment studies are absent given the tumor’s rarity and pattern of recurrence that requires an extended posttreatment observation period. The behavior of the tumor varies from an indolent slow-growing neoplasm to that of a highly aggressive and locally invasive malignancy with a capacity for regional and distant metastases. Unfortunately, ENB is typically diagnosed after extensive local spread. However, the advances in surgical and radiation techniques and the use of novel chemotherapeutic approaches have lead to the development of an evolving array of encouraging treatment options reported on this diagnosis.

Traditionally, surgery using a craniofacial resection (with a transfacial approach and craniotomy) and adjuvant radiation therapy have been the mainstay of treatment of patients with resectable disease. Endoscopic resection has gained popularity for selected lesions and can spare some patients the morbidity of facial incisions and even craniotomy while remaining an oncologically sound operation. Neoadjuvant, concurrent, and adjuvant chemotherapy (single agent and combination) has been used in combination with surgery and radiation therapy to exploit ENBs’ biologically similarity to other tumors of neural crest cell origin that are also chemosensitive.

This article will review the typical presentation, diagnostic assessment, and various treatment options that have been advocated for ENB, while illustrating the limitations of staging and the impact of long-term recurrence on advocated treatment strategies.

Introduction

Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB), also known as olfactory neuroblastoma, is an uncommon malignancy of the head and neck, representing only 3% to 6% of nasal cavity and sinonasal neoplasms. First described by Berger, Luc, and Richard in 1924, ENB is a tumor of neural crest origin that is considered to arise from the olfactory neuroepithelium of the olfactory cleft in the superior nasal cavity at the anterior skull base. Local spread of tumor can extend throughout the paranasal sinuses and skull base with invasion of the orbit, cavernous sinus, and brain.

Several treatment approaches for ENB have been described in the literature, but rigorous, prospective treatment studies are absent given the tumor’s rarity and pattern of recurrence that requires an extended posttreatment observation period. The behavior of the tumor varies from an indolent slow-growing neoplasm to that of a highly aggressive and locally invasive malignancy with a capacity for regional and distant metastases. Unfortunately, ENB is typically diagnosed after extensive local spread. However, the advances in surgical and radiation techniques and the use of novel chemotherapeutic approaches have lead to the development of an evolving array of encouraging treatment options reported on this diagnosis.

Traditionally, surgery using a craniofacial resection (with a transfacial approach and craniotomy) and adjuvant radiation therapy have been the mainstay of treatment of patients with resectable disease. Endoscopic resection has gained popularity for selected lesions and can spare some patients the morbidity of facial incisions and even craniotomy while remaining an oncologically sound operation. Neoadjuvant, concurrent, and adjuvant chemotherapy (single agent and combination) has been used in combination with surgery and radiation therapy to exploit ENBs’ biologically similarity to other tumors of neural crest cell origin that are also chemosensitive.

This article will review the typical presentation, diagnostic assessment, and various treatment options that have been advocated for ENB, while illustrating the limitations of staging and the impact of long-term recurrence on advocated treatment strategies.

Epidemiology

ENBs represent only 0.3% of all upper aerodigestive tract malignancies and 3% to 6% of all sinonasal malignancies. A bimodal age distribution has classically been described for ENB, but recent Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data and meta-analyses support a unimodal age distribution with a reported mean age of presentation ranging from 45 to 56 years of age.

Of note, approximately 7% to 20% of patients present at between 10 and 24 years of age. The impact of age on prognosis is unclear, with one study showing no impact, whereas univariate analyses in other studies suggest an impact on survival in patients diagnosed older than 65. One study suggests that pediatric patients with ENB present with more aggressive local disease that typically requires combined modality care. There is no defined cause and no sex or race predilection. There is no specific laterality that is more common in presentation.

Patient evaluation

Clinical Presentation

Patients with ENB present with symptoms related to the local extension of their tumor. Initial symptoms are typically unilateral nasal obstruction (53%–100%), epistaxis (10%–52%), headache (10%–20%), and hyposomia/anosmia (6%–35%). With extension of disease outside the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, symptoms of orbital and cranial involvement can manifest. Up to 20% of patients will present with orbital symptoms, including visual loss, diplopia, epiphora with nasolacrimal obstruction, and proptosis. Headaches, nausea, and vomiting can be indicative of dural or intracranial involvement. Rarely, patients will present with frontal lobe symptoms, seizures, or symptoms of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

Advanced stage presentation is common because of the subtlety of the initial presenting symptoms, which may be initially mistaken as inflammatory or infectious sinonasal disease. The average reported delay between the appearance of first symptoms and diagnosis is 6 months ; however, the median time to diagnosis by radiographic imaging after onset of first symptoms was as long as 23.1 months in one study.

A listing of differential diagnoses (clinical and histopathologic) for ENB is given in Box 1 .

Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC)

Sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma

Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC)

Merkel cell carcinoma

Ewing’s sarcoma

Metastatic pulmonary small cell NEC

Small cell lymphoma

Atypical extracranial meningioma

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Pituitary adenoma

Melanoma

Diagnosis

Clinical examination

Rigid nasal endoscopy often reveals a reddish gray pedunculated mass with a smooth surface that readily bleeds with manipulation ( Fig. 1 ). Given the enhanced vascularity of ENBs, biopsy is typically performed in the operating room to control potential hemorrhage. Additionally, the tumor’s close proximity to the orbit and anterior cranial fossa warrant obtaining imaging before endoscopic biopsy.

Most series report that less than 15% of individuals present with regional nodal metastasis at the time of initial evaluation. Zafereo and colleagues noted that 22% their patients were stage N+ at diagnosis. Office-based fine needle aspiration may assist in appropriate staging and establishing the need for treatment of the neck in these patients.

Imaging

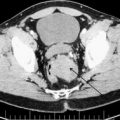

Initially, imaging is obtained to distinguish between inflammatory and neoplastic causes given a patient’s symptoms and clinical examination findings. This is usually accomplished with a fine-cut computed tomography (CT) scan of the paranasal sinuses. If a neoplastic process is suspected, CT can be used to identify bony erosion of the cribriform plate and lamina papyracea, but magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is also needed for a thorough evaluation. On CT, ENB can display isodensity or slight hyperdensity with scattered necroses and marginal cysts.

MR imaging is superior to CT scanning at delineating the extent of the tumor and distinguishing it from inspissated sinonasal secretions, which can have a significant impact on the surgical approach or treatment planning for radiation. Fine-cut cross-sectional imaging for coronal and sagittal reconstructions aid in identifying intracranial, orbital, and pterygopalatine fossa involvement. MR imaging is also superior at showing dural enhancement, perineural spread, and submucosal extension. ENB is best evaluated with fat-suppressed, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images and will be hypointense on T1-weighted images and have a heterogeneous hyperintensity on T2-weighted images with variable enhancement.

Figs. 2–5 feature various levels of Kadish staging of ENB imaged with CT and MR imaging.

Intracalverial invasion is generally considered poor prognostic finding. Using pretreatment CT and MR imaging, Yu and colleagues classified direct intracranial extension in Kadish stage C ENB into 3 different categories based on extent of invasion. These patterns of invasion were cranio-orbital-nasal-communicating ENB, cranio-nasal-communicating ENB (most common), and orbital-nasal-communicating ENB. Response to therapy was not correlated to pattern of invasion in this series.

Clinical staging should be completed with a metastatic assessment for cases with advanced local disease or regional metastasis on presentation. In one meta-analysis, 1.5% of patients presented with distant metastases at initial diagnosis. Wu and colleagues showed ENB was positron-emission tomography (PET) positive in 7 of 9 patients (77.7%) with a maximal standard uptake value (SUV max ) of 6.37 ± 4.22 in primary tumors. Tracer uptake did not correlate with tumor size. PET/CT detected regional metastases in 2 (cervical and parapharyngeal) patients and distant metastases in 4 (lung, liver, and bone). PET/CT altered the clinical staging in 3 of the 9 patients. The use of pretreatment PET/CT has also been advocated by other authors.

Pathologic Conditions

Olfactory epithelium contains 3 types of cells: basal, olfactory neurosensory, and sustentacular. ENB is thought to arise from the mitotically active basal cells that give rise to neuronal and sustentacular cells. Molecular studies have suggested ENB may be a member of the Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor group of tumors.

ENB is categorized as a “small, round, blue cell tumor” on light microscopy. The cells can have indistinct cytoplasmic borders, hyperchromatic nuclei, infrequent mitoses, and rare nucleoli. Additionally, ENB demonstrates a highly vascularized stroma that is infiltrated with nests of cells. Two types of rosettes are seen. Homer-Wright (HW) rosettes, also known as pseudorosettes, are present in approximately 30%–50% of cases. They are characterized by neurofibrillary and edematous stroma in the center of a cuffing arrangement of cells. Flexner-Wintersteiner rosettes, also known as true rosettes, are seen in up to 5% of cases and distinguished by a tight annular arrangement with glandlike spaces.

The extent of differentiation is classified by the Hyams grading system based on histologic features including architecture, mitotic activity, nuclear pleomorphism, rosettes and necrosis ( Box 2 , Figs. 6 and 7 ).

Grade 1 – Well differentiated with lobular preservation, prominent fibrillary matrix, no nuclear pleomorphism, Homer-Wright (HW) rosettes

Grade 2 – Low mitotic index, moderate nuclear polymorphism, fibrillary matrix present, HW rosettes

Grade 3 – Moderate mitotic index, prominent nuclear polymorphism, low fibrillary matrix, HW rosettes, rare necrosis

Grade 4 – High mitotic index, anaplasia, marked nuclear pleomorphism, absence of fibrillary matrix and HW rosettes, frequent necrosis

The literature typically refers to ENB as low grade, consistent with Hyams grade 1 or 2, or high grade (grades 3 or 4). The diagnosis of a high-grade ENB has been shown to have a significant impact on survival. In a retrospective review by Dias and colleagues, the 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) for patients with low-grade tumors was 64%, whereas for patients with high-grade tumors it was 43%.

The importance of a patient’s tumor histopathologic findings, as they relate to prognosis, vary among reports. Levine and colleagues found no valuable pathologic or molecular indicators to predict aggressive clinical behavior in their series of patients. Morita and colleagues examined the pathologic findings of 49 patients with ENB and noted the pathologic grade correlated with prognosis. Patients with low-grade lesions were able to undergo surgery alone if negative margins were obtained with resection. The authors advocated that patients with high-grade lesions be treated with surgery and postoperative radiation with a consideration for the inclusion of chemotherapy.

Care must be taken when interpreting older studies in which the histopathologic differentiation of similar yet distinctly unique sinonasal tumors, such as SNUC or neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), may have been combined under the diagnosis of ENB. Some authors have even suggested the seemingly dichotomous behavior of the tumor may be an indication of this problem. ENBs are typically considered low-grade tumors that respond well to treatment. However, when an ENB is considered a high-grade or anaplastic variant and actively progresses despite standard combined modality therapy, the potential for initial misdiagnosis should be considered.

Cohen and colleagues, at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), reviewed the pathologic findings of 12 previously diagnosed cases of ENB and were able to confirm diagnosis in only 2. Misdiagnoses included 2 cases of melanoma, 3 cases of NEC, 3 cases of pituitary adenoma, and 2 cases of SNUC. The change in diagnosis would have lead to a significant alteration in the patient’s original treatment plan in 8 of the 10 patients.

Immunohistochemistry demonstrates that greater than 90% of ENB cells are neuron-specific enolase positive. Approximately 80% of cases are positive for S-100, staining cell nests, and synaptophysin. Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and epithelial membrane antigen are typically negative with ENB. SNUC demonstrates greater pleomorphism than ENB, may contain enlarged nucleoli, and is EMA positive and S-100 negative.

Kim and colleagues examined 17 ENB specimens for staining with bcl-2, p53, MIC-2, and N-myc. Of note, 70% of specimens were positive for bcl-2. All specimens were negative for N-myc. MIC-2 and p53 staining was noted in only one specimen. The results suggested a potential survival advantage and improved response to chemotherapy with bcl-2 positivity in patients with ENB, yet this finding was not statistically significant.

In patients with regional lymphadenopathy, fine needle aspiration can be considered a diagnostic aid. Mahooti and Wakely reviewed 6 fine needle aspiration samples for cytopathologic features of ENB and noted specimens were typically nonspecific. However, if fibrillar neuropil was identified in the context of a patient with an established diagnosis of ENB, the confirmation of metastatic spread could be confirmed with cytometry. The histologic findings noted on aspirates can be mistaken for rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, lymphoma, extracranial meningioma, poorly differentiated NEC, or pituitary adenoma.

Clinical Staging

There are 2 major clinical staging systems for ENB. The Kadish staging system, originally reported in 1976 with the pretreatment assessment of 17 patients with ENB, has traditionally been the one most commonly reported. Proposed by Morita, and later used by Jethanamest and colleagues, a modification to the initial 3-tier Kadish staging system was created that included an additional stage for patients who had distant metastases at the time of diagnosis (stage D). Tumors are staged based on their anatomic involvement ( Box 3 ).

Stage A: Limited to the nasal cavity

Stage B: Involves the paranasal sinuses

Stage C: Extends outside the sinonasal cavity, including involvement of the base of skull, orbit and intracranial cavity

Stage D: Distant metastases at diagnosis

The Kadish system has been shown to correlate with survival. A criticism of the Kadish system is that it fails to completely stratify patients. Very few patients actually present at stage A and a wide spectrum of presentations can be grouped within stage C. Reports that were published before the addition of stage D with the modified system allowed patients with intracranial extension and distant metastases to be initially staged identically. An additional weakness cited in the Kadish system was that it did not allow for stratification of patients with pathologic adenopathy.

It should be noted that radiologic staging and tumor grading are not directly related. In one report, only 14% of Kadish A tumors were low grade based on Hyams’ grading.

Dulguerov proposed a TNM style of staging system for ENB that allowed for the inclusion of nodal status ( Box 4 ). Some authors have commented that the Dulguerov classification more closely correlates with survival and recurrence.

T1: limited to the sinonasal cavity excluding the sphenoid sinus

T2: involves the cribriform plate or sphenoid sinus

T3: involves the orbit or anterior cranial fossa without dural involvement

T4: tumors with intracranial involvement

N1: any lymph node metastasis

M1: any distant metastasis

Treatment

The rarity of presentation and lack of controlled trials have resulted in a wide variation in the management of ENB. As a general rule, sinonasal malignancies are best managed with a multidisciplinary approach. There is a sufficient body of evidence to suggest that for advanced-stage ENB, such as Kadish C lesions, a combined modality approach improves disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with surgery or radiation alone.

For Kadish A lesions, the consensus for treatment approach diverges significantly and monomodality care has been explored. Surgical management has evolved beyond open approaches to now include endoscopic management options. Radiation has expanded to include approaches that now use proton therapy. Controversy continues to exist relative to the role of chemotherapy, the most appropriate agents to use, and the timing of administration. The following section provides a review of the published literature as it applies to these various issues.

Surgical Management

Most of the literature examining the treatment of ENB consists of retrospective institutional reviews. Surgery, primarily using a craniofacial resection (CFR) approach, has been the traditional treatment modality in the initial care of these patients. Exposure is obtained through a coronal scalp incision and bifrontal craniotomy ( Fig. 8 ) from above and through a lateral rhinotomy facial incision with potential extension under the ipsilateral eyelid (Weber-Ferguson approach) from below. This approach can allow for excellent exposure and en bloc resection of the tumor ( Fig. 9 ). Reconstruction typically involves placement of a pericranial flap to create a vascularized flap separation of the nasal cavity from the intracranial contents ( Fig. 10 ). Criticisms of this approach include cosmesis-related concerns from the mid-facial incision and frontal lobe trauma from intraoperative retraction.