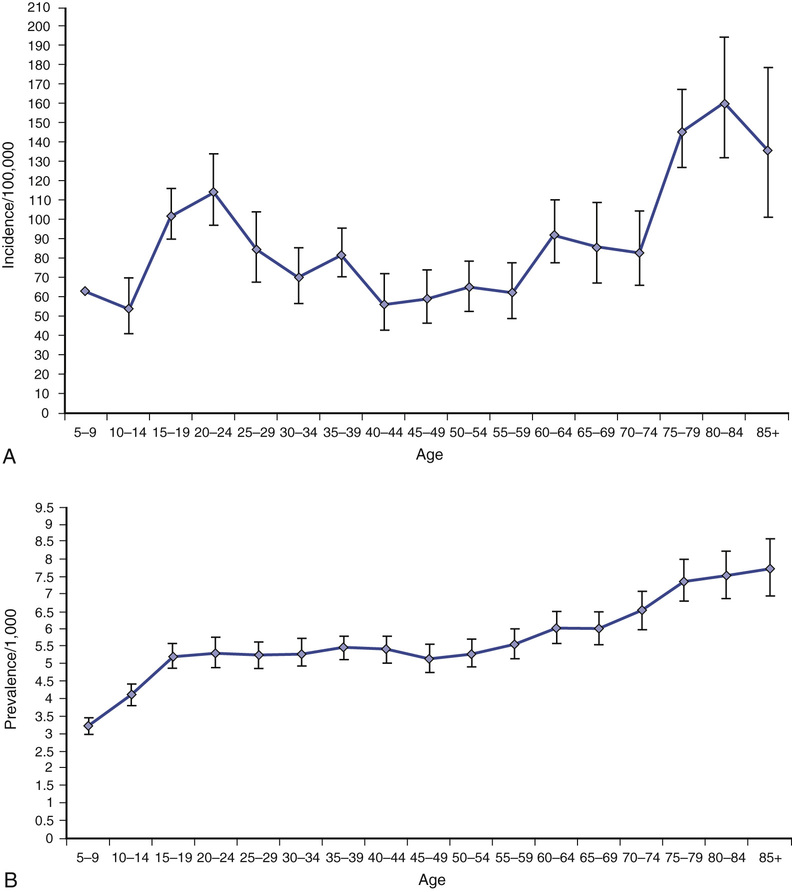

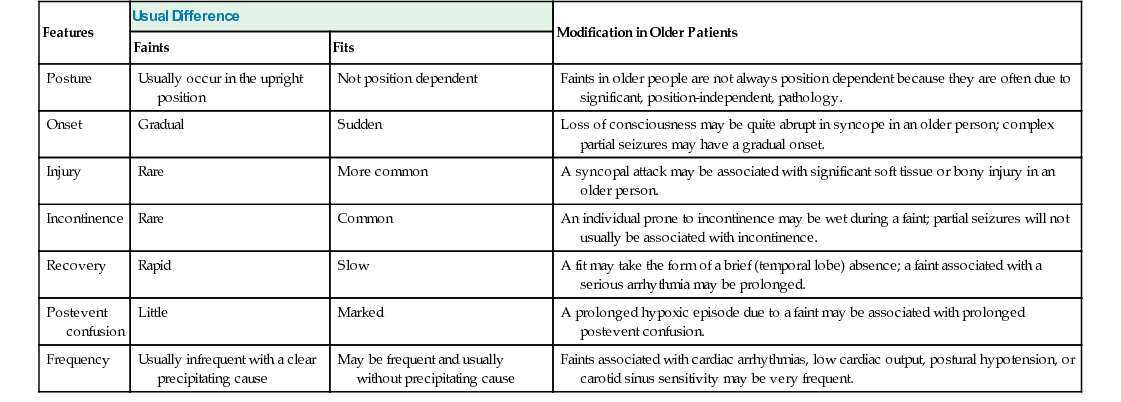

Khalid Hamandi Epileptic seizures are typically short lived and transitory but nonetheless have the potential for considerable disability because of the unpredictable nature of attacks, the risk of injury they bring, and neurologic impairment from repeated seizures and adverse effects of treatment.1 Driving is restricted, and there is social embarrassment, stigma, and impact on employment.2–4 Fundamental questions regarding the neurobiology of epilepsy, reasons for its development, factors that make seizures start and stop, and the variable response to treatments remain unanswered. Epilepsy in older adults needs special consideration.5 An older adult with presenting symptoms that suggest a diagnosis of epilepsy can be a considerable clinical challenge.5,6 Diagnosis rests on the history of events obtained from the patient and a reliable witness. There are no clinical signs that can be elicited in a clinic, beyond directly observing a seizure, to support the diagnosis, and tests can have normal results or show nonspecific abnormalities that catch the unwary. The differential diagnosis of collapse or altered consciousness in older adults is wide. A previous diagnosis of epilepsy made earlier in life might not explain new or ongoing attacks and the term known epileptic (seen in some medical records) should be avoided. Older people with a diagnosis of epilepsy can be considered as falling into four groups: An epileptic seizure is the clinical manifestation of an abnormal synchronous neuronal discharge. Epilepsy is defined as a tendency toward recurrent epileptic seizures. A diagnosis of epilepsy is not appropriate after a single event.7 In older adults the likelihood of further seizures can be more likely when the seizure has occurred as a result of a structural brain lesion.8–10 Traditionally the ability to predict who will develop epilepsy after a first seizure was deemed insufficient to warrant the label or treatment. In 2014 the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) published new proposals for the operational definition of epilepsy, which included “one unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures (at least 60%), occurring over the next 10 years.” A seizure occurring at least 1 month after a stroke was provided as an example in this new operational definition.11 The proposals have undergone much discussion and scrutiny within the epilepsy community. For example, what is the evidence base, and how does one calculate recurrence risk after one seizure even in the presence of intracranial pathology? The level of adoption of these new proposals remains to be seen. Epilepsy is the third most common neurologic condition in old age after dementia and stroke.11 The incidence is two to three times higher than that seen in childhood.6 A community study, the United Kingdom General Practice Survey of Epilepsy and Epileptic Seizures, found that 24% of newly diagnosed cases of definite epilepsy occurred in people aged older than 60 years.9,12 A significant rise in incidence with increasing age has been confirmed in several studies, from an overall incidence of 50 per 100,000, to 70 to 80 per 100,000 in adults older than 60 years and 160 per 100,000 in adults older than 80 years13–16 (Figure 58-1). The prevalence of epilepsy is generally taken as between 5 and 10 cases per 1000 persons, with a lifetime prevalence of 2% to 5%.17 Rates are dependent on case ascertainment and agreement on definitions used, for example, active epilepsy (ongoing seizures) versus controlled epilepsy.18 In light of these data, there would appear to be relative underprovision in specialist care for older people with epilepsy. The reasons for this are unclear, but possible explanations include a lesser perceived impact on lifestyle in older people with epilepsy compared to their younger counterparts, or less focus on the condition in older patients in light of more pressing clinical issues such as associated or unrelated comorbidities.19 Epilepsy classification might be considered by generalists as overly complex. This need not be the case if the principles behind the classification schemes are better understood. The current classification of epilepsy was developed by the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology. There are two parallel schemes: one for epileptic seizures20 and another for epilepsy syndromes.21 In 2010 the ILAE proposed a further revision, mostly around terminology to reflect new concepts (discussed in detail in the following sections).22 Accurate syndromic classification helps direct treatment decisions and provide information on prognosis. Classification is also important for epidemiologic studies and service needs assessments. Furthermore, rigorous attempts at classification benefit the whole diagnostic process and reduce, or identify, previous epilepsy misdiagnoses. A good understanding of epilepsy syndromes that occur in childhood or early adult life remain useful when dealing with older patients because seizure risk can persist throughout life, patients may carry a diagnostic label that may not be correct, and questions regarding the continuation of long-standing medication may be raised. Several areas of confusion seem to arise in epilepsy classification in the nonspecialist setting. Typically confusion arises from the use of outdated terminology or from the failure to distinguish between terms intended to describe seizure types and those intended to designate epilepsy syndromes or some causal substrate. Epilepsy is not a specific disease but a heterogeneous group of disorders manifesting the neuroanatomic and pathophysiologic substrate causing the seizures. A useful schema from the ILAE considers five parts, or axes, organized in a hierarchic fashion allowing the integration of available and new information.23 The five axes are as follows: Axis 1: Ictal phenomenology—describing in detail the seizure event Axis 3: Syndrome—with the understanding that a syndromic diagnosis may not always be possible Axis 4: Cause—includes a specific disease, genetic defects or pathologic substrates causing seizures This five-axis scheme has not been adopted widely in a formal sense. However, it remains a useful framework for clinicians who have patients with epilepsy, and it is used in some form by most epileptologists and epilepsy clinics. It can be applied in any setting, essentially considering in each case (1) the seizure type, (2) brain area or areas involved, and (3) the cause or syndrome.24 The precise terminology, and how it is applied, remains under debate and is likely to continue until the precise mechanisms and causes of epileptic seizures are defined to replace what are, in many cases, concepts and descriptions. The long-running debate of how best to classify epilepsy continues.23 Changing lists of descriptive entities inevitably cause confusion. A simplified system based on causation rather than descriptive terminology would be preferred, particularly with advances in imaging and genetics.25 However, knowledge is insufficiently complete for a reliable causative classification to allow this at this stage. Perhaps the main limitation of the ILAE classification scheme is its poor dissemination among nonepilepsy specialist health care professionals. Revisions in the classification scheme and the rationale behind the revisions tend to be published in specialist journals and as such remain relatively inaccessible to nonepilepsy specialists. Given that epilepsy is so commonly encountered, this is one area that should be addressed. The terms grand mal and petit mal are still commonly heard from patients and some practitioners; they are, however, outdated terms and should be avoided. Although they may provide a reference to a seizure type, they give little indication of the true seizure semiology, the possible pathophysiology, or even a secure diagnosis. Patients may use the term grand mal to refer to any big episode, either a complex partial seizure or a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. Similarly, petit mal can be used to refer to any brief alteration of consciousness and needs additional history to define the event further. Despite any shortcomings in epilepsy classification, those involved in the care of patients with epilepsy, or episodes that might be attributed to epilepsy, should familiarize themselves with the current scheme and in particular the principles behind it. The International Classification of Epileptic Seizures (ICES) was developed by a panel of international experts examining video recordings of clinical and electroencephalographic seizures20 and linked to Axis 2 of the ILAE publication described earlier.23 It is based on a consensus of opinions. Box 58-1 shows the current recommended classification of epileptic seizures. By design the categories are descriptive. The first level of this system distinguishes between generalized seizures, a seizure whose initial semiology indicates, or is consistent with, “originating at some point within, and rapidly engaging, bilaterally distributed networks. Such bilateral networks can include cortical and subcortical structures, but do not necessarily include the entire cortex”22; and focal seizures, a seizure whose initial semiology indicates, or is consistent with, involvement of more localized or lateralized brain area. These are categorized into absence, myoclonic, tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic events. Absence seizures can be subcategorized into typical absence and atypical absences. Typical absences are seen in idiopathic generalized epilepsy (see later section). They occur in childhood-onset syndromes but can persist into old age. (Typical absence seizures of childhood were previously referred to as petit mal, but this term is now considered obsolete.) They consist of an alteration of consciousness. Occasionally there is associated eye flickering, but other motor manifestations are rare. Attacks are brief; they last usually less than 30 seconds. Characteristic electroencephalogram (EEG) findings are of generalized spike wave discharges of 3 to 5 Hz. Myoclonic jerks are brief muscular jerks affecting the limbs and, less commonly, the trunk. The term myoclonic jerk comes under the heading of generalized seizures. However, myoclonic jerks do occur in focal epilepsy, affecting one limb or side; if strictly following the ILAE scheme, these would be classified as focal motor seizures. These are separated into motor, somatosensory or special sensory, autonomic, and psychic. The term localization-related, previously proposed for focal seizures, is cumbersome and not widely adopted. The terms focal and partial remain in more common use. For the past few decades, focal seizures have been separated into simple partial seizures (consciousness is preserved, awareness is maintained) or complex partial seizures (consciousness is lost). The preservation or loss of consciousness is very relevant in the clinical setting, as it indicates a level of impairment caused by seizures. A seizure aura, often taken to be the warning before a seizure, is a simple partial seizure that may immediately precede a complex partial seizure or secondary generalization. Auras can occur in isolation (i.e., a simple partial seizure). Auras are typically short lived, lasting from seconds to a few minutes but rarely longer. These are perhaps the most familiar of all focal seizure types. Seizures either arise from mesial temporal structures, part of the limbic system (e.g., the hippocampus), or from the temporal neocortex. Symptoms at onset include epigastric discomfort, “butterflies” or a rising sensation, abnormal taste, experiential phenomena such as déjà vu, and psychic features, fear, or euphoria. These symptoms are usually short lived, lasting from seconds to a few minutes, and can occur in isolation without progression to the loss of awareness of secondary generalization. Patients will often recall these initial symptoms as seizure auras. A complex partial seizure of temporal origin will typically manifest with orofacial automatism (e.g., lip smacking or repeated swallowing). This is an extremely useful piece of history from a witness, and specific inquiry is helpful. In addition, there may be limb automatisms and typically there is dystonic posturing. Patients typically feel tired with the need to sleep after an attack. Frontal lobe seizures vary greatly because of the size of the frontal lobe and the many functions it subserves. The semiology of frontal lobe seizures depend on the origin and spread of the epileptogenic focus.26 The frontal lobe contains the primary motor cortex, supplementary motor cortex, prefrontal cortex, and the limbic and paralimbic cortices. In general, frontal lobe seizures manifest with prominent motor features. There may be forced head version or forced eye deviation. Limb involvement can include tonic, clonic, or postural movements or bilateral vigorous motor automatisms, for example, bicycling. Sometimes bizarre motor movements are seen; occasionally patients can retain consciousness even with jerking in all four limbs. These features can lead to an incorrect diagnosis of nonepileptic seizures. A “Jacksonian march” refers to a march or spread of the focal motor seizure in a predictable and sequential manner from a distal limb to proximal areas or from leg to arm. The term Todd paresis refers to a transient hemiparesis that can last a day or more occurring after a secondary generalized focal motor seizure. Occipital onset seizures manifest, as would be expected, with visual phenomena. Typically these are vivid or formed hallucinations. They are distinct from migraine aura in that colors are vivid and evolve over seconds rather than the several minutes of a migraine aura. They may involve flashing balls of light or revolving bright colors. Other manifestations include well-formed hallucinations, which are of a short duration of seconds to minutes and may evolve to secondary generalized seizures. Parietal lobe seizures are rare.27 The parietal lobes are involved in the processing and integration of sensory and visual information. Stereotyped episodes that involve pain, numbness and tingling, heat, or pressure sensations suggest parietal lobe seizures. The International Classification of Epilepsies and Epilepsy Syndromes (ICEES)21 supplements the ICES. Some epilepsy categories represent pure disease entities, whereas others represent a spectrum of clinical forms (e.g., idiopathic generalized epilepsy). The concepts of generalized and focal are no longer recommended in the classification of syndromes. Classification is based on causative concepts: idiopathic, epilepsy occurring alone (Greek idios) without apparent underlying pathology; symptomatic, with a known underlying cause; and cryptogenic, with an unknown but suspected underlying cause. The most recent ILAE revision proposes the following change in terminology: idiopathic is to be referred to as genetic, symptomatic as structural/metabolic, and cryptogenic as unknown.22 Again, the extent of adoption of all aspects of this new terminology remains to be seen. Idiopathic (or genetic) generalized epilepsy (IGE) is characterized by one or more of the following seizure types: typical absences, myoclonic jerks, and generalized tonic-clonic seizures; interictal and ictal generalized spike or polyspike and wave on EEG. The term genetic generalized epilepsy has been proposed by the ILAE22 and is now seen in many publications and is used clinically, but wide-scale adoption of the term in favor of IGE is probably best left until the true genetic architecture of the epilepsies is understood.26 Further syndromic subclassification of IGE is made on the prevalence of the different seizure types and EEG features. The inclusion of age of onset and diurnal seizure patterns are proposed by some. The main subgroups seen in adults with epilepsy are the following: It still remains debated whether different clinical manifestations represent different ends of a biologic continuum or a group of distinct syndromes.28 The typical onset age of IGE is childhood or early adult life. However, a later onset form is recognized,29,30 and there are case reports of classical IGE presenting for the first time in older adults.31,32 The term idiopathic refers to a disorder unto itself, sui generis (i.e., without other neurologic abnormality) and not etiology unknown. The risk of seizures in individuals with IGE usually continues into old age. A late presentation of absence status in four patients older than 60 years with a prior diagnosis of IGE and absence seizures that resolved in their second decade has been reported.33 Response to appropriate antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment is good in most, but not all. One study of epilepsy patients with IGE older than age 60 found a small subgroup who experienced an exacerbation of seizures in old age.34 Symptomatic epilepsy is the predominant cause of new-onset seizures in older adults.19,35 Symptomatic epilepsy means a cause is known or can be reasonably postulated. In the absence of an imaging abnormality, a history of a prior brain injury (e.g., from intracranial infection [meningitis or encephalitis] or trauma) can be sufficient to attribute a cause to new-onset seizures. The term remote symptomatic is used for patients who develop seizures some years after a significant brain injury, in contrast to acute symptomatic in which epilepsy is a presentation of new brain dysfunction. In older adults, the likelihood of finding abnormalities, particularly leukoaraiosis, on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is high.36 The relationship of such abnormalities to epilepsy, and why some develop seizures and other not, remains unclear.37 Epilepsy can present with disparate symptoms. Similarly, several other conditions can present with features that may be mistaken for epileptic seizures. The key feature in epilepsy is that episodes are typically stereotyped, unchanged over a long period of time, and usually short lived. The following episodic manifestations occurring in isolation, or in combination, can be caused by epilepsy: • Loss of awareness or consciousness • Generalized convulsive movements • Sensory episodes—tingling, pain, burning • Vocalization—formed speech, incomprehensible words, screams, or laughter • Episodic phenomena from sleep The importance of gathering a careful history before making a diagnosis of epilepsy cannot be overstated. The history should include a description of events from the patient and, crucially, a firsthand description from a witness. Overreliance on a secondhand statement such as “It looked like a fit” is likely to lead to a misdiagnosis. There is no single test to make a diagnosis of epilepsy, and time taken by an experienced clinician in taking a careful history cannot be circumvented. In each case, an account of the circumstances, time of day, situation, prodrome or warning, detailed account of the attack, the semiology and duration of the attack, rate and nature of recovery, and associated symptoms or signs (e.g., headache or confusion) are needed. Direct questions about the attack itself and other previous attacks are helpful, but care should be taken not to lead the history; these questions are best left until the patient and witness have given a free account of the event or events in question. Useful features that are worth inquiring about directly, if not first offered, include head or eye deviation, the nature of limb movements, posturing, jerks or automatisms, and whether movements are rhythmic or synchronous and how they evolved over time. Asking a witness about repeated swallowing or lip smacking can be revealing. Any change of color, breathing pattern, and sweating need to be ascertained along with an account of the recovery period, its duration, and any subsequent symptoms such as headache, confusion, or altered behavior. It is always useful to ask about possible prior attacks that the patient may not associate with their current event; for example, a patient presenting after his or her first generalized tonic-clonic seizure may not make the link between previous experiences of focal seizures, common examples being epigastric sensations, déjà vu, or abnormal tastes or smells. Classically tongue biting and incontinence were thought to strongly indicate an epileptic seizure. This is not always the case. Urinary incontinence can occur during syncope, and injury to the tip of the tongue can occur in syncope although if the sides of the tongue or inner cheek are severely bitten, this usually indicates that a generalized tonic-clonic seizure has taken place.38 The past medical history should include inquiries about previous history of head injury, intracranial infection, stroke, dementia, and cardiac history. Family history, medication history, and social history are important as in any other presentation. Specific inquiry should go into living arrangements, driving, occupation, and hobbies or pastimes. The two main differential diagnoses of epileptic seizures to consider are syncope and psychogenic or nonepileptic attacks. Manifestations of both epileptic seizures and syncope may differ in older adults compared to the young, making diagnosis difficult or increasing misdiagnosis. Other rarer conditions leading to blackouts or altered consciousness to consider are hypoglycemia (common in older people with diabetes), other metabolic disorders, structural abnormalities at the skull base affecting the brain stem, and lesions affecting cerebrospinal fluid circulation. Transient cerebral ischemia or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are usually easily separated from epileptic events by their frequency and time course. They rarely present with loss of consciousness and TIAs are typically less frequent and do not remain stereotyped over long periods of time. One exception is focal seizures affecting the hand seen in critical cortical ischemia. This is described in more detail later in this chapter. Syncope is the most common cause of episodes of loss of awareness. Syncope is covered in greater detail in Chapter 45. Aspects of an attack should not be taken in isolation and given undue emphasis as elements of epileptic seizures can occur in syncope. Key features of syncopal episodes versus epileptic seizures are the precipitating factors, warning symptoms, a brief loss of consciousness, and rapid recovery, although there can be greater variation in older people (Table 58-1). Features that may mimic seizures include head turning, automatisms, urinary incontinence, and relatively minor tongue biting.39 Injury can occur from a syncopal fall, although this is less common because people tend to crumple to the floor rather than the fall stiffly as in an epileptic seizure. In cardiac syncope, attacks occur without warning; there is abrupt unprovoked collapse with brief unconsciousness and rapid recovery. They are not situational and there is less often a prodrome than in vasovagal syncope. Cardiac syncope should be strongly suspected in those with a history of structural heart disease, previous myocardial infarction, rheumatic fever, or heart murmur. Episodes that outwardly appear similar to epileptic seizures but are not caused by ictal electric discharges in the brain are referred to by a number of terms: nonepileptic attacks, nonepileptic seizures, psychogenic nonepileptic attacks (PNEAs) or seizures, or the less favored pseudoseizures.40 The prevalence of PNEA appears lower in older adults, although no studies have examined ascertainment bias or reporting bias. In a study of video-EEG monitoring in older people (>60 years), PNEA was diagnosed in 10 of 34 patients who had recorded events during the monitoring period41; this series came from 71 patients older than 60 years who had undergone video-EEG monitoring out of a total of 440 over a 7-year period. Another study42 reported a diagnosis of PNEA was made in 7 of 16 patients older than 60 years undergoing video-EEG monitoring; this was from a total of 834 admitted for long-term video-EEG monitoring. Further study of long-term video-EEG monitoring over an 8-year period identified 39 patients admitted for evaluation older than age 60 years, 13 of whom were diagnosed with PNEA on the basis of video-EEG.43 Nevertheless, PNEA remains an important differential diagnosis in older adults, particularly when apparent medically refractory epilepsy is encountered.41 PNEA probably arises as a result of patients responding to psychosocial stress with unexplained somatic symptoms that come to medical attention,42,44,45 and PNEA is associated with a number of distinct pathologic personality profiles that could be used to tailor therapy.46 Somatoform disorders, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and a reinforced behavior pattern are all features associated with PNEA. In one study, a subgroup of older patients with PNEA were more likely to be male and more likely to have a history of traumatic experience related to ill health.47 Suspicion of PNEA should be raised where there are unusual features to the attacks, associated physical or mental ill health, adverse social circumstances, or bereavement prior to presentation. Confidently securing a diagnosis of PNEA usually requires long-term video-EEG monitoring, an investigation that would appear to be of limited access to the older adult population in most centers. The Cochrane database review in 2007, and again in 2014, found insufficient evidence to recommend specific treatments for PNEA and stressed the need for new randomized trials to assess treatment interventions.48 One of the first aims of treatment following a diagnosis of PNEA should be to reduce unnecessary medical interventions or hospital admissions. Transient epileptic amnesia (TEA) has been used to describe recurrent episodes of transient amnesia in the absence of overt seizures.49 TEA needs to be distinguished from transient global amnesia (see next subsection). In TEA there is evidence for a diagnosis of epilepsy based on one or more EEG abnormalities, co-occurrence of other clinical features of epilepsy (e.g., automatisms or olfactory hallucinations), and clear-cut response to antiepileptic medications.50 Other features include interictal memory disturbance manifested by accelerated forgetting, remote autobiographic amnesia (i.e., patients demonstrate a patchy but dense loss of memories for important personal events from the remote past), and topographic amnesia (i.e., difficulty navigating their way around new or familiar route).51,52 It is not clear whether episodes of TEA represent ongoing ictal activity or a postictal phenomenon. Whether TEA is a sufficient diagnostic entity to be regarded as a distinct syndrome53 or another manifestation of temporal lobe seizures in older adults remains to be clarified.

Epilepsy

Introduction

Definition

Epidemiology

Classification

Shortcomings of Existing Classification Schemes

Epileptic Seizures

Generalized Seizures

Focal Seizures

Temporal Lobe Seizures

Frontal Lobe Seizures

Occipital Seizures

Parietal Seizures

Epilepsy Syndromes

Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsy

Symptomatic Epilepsy

Making the Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Syncope

Psychogenic Attacks

Transient Epileptic Amnesia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Epilepsy

58