Chapter 24

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Melanie Sklar and Lesley Haynes

Introduction

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) comprises a group of rare genetically determined skin blistering disorders characterised by extreme fragility of the skin and mucous membranes.

Types

The most recent classification [1] separates EB into four main types which are further divided into subtypes:

- Simplex (EBS) – suprabasal and basal, including EBS-Dowling Meara and EBS-Localised (previously known as EBS-Weber Cockayne)

- Junctional (JEB) – Herlitz (HJEB) and others, including non-Herlitz JEB (NHJEB)

- Dystrophic (DEB) – dominant (DDEB) and recessive (RDEB)

- Kindler syndrome – has recently been added to this classification

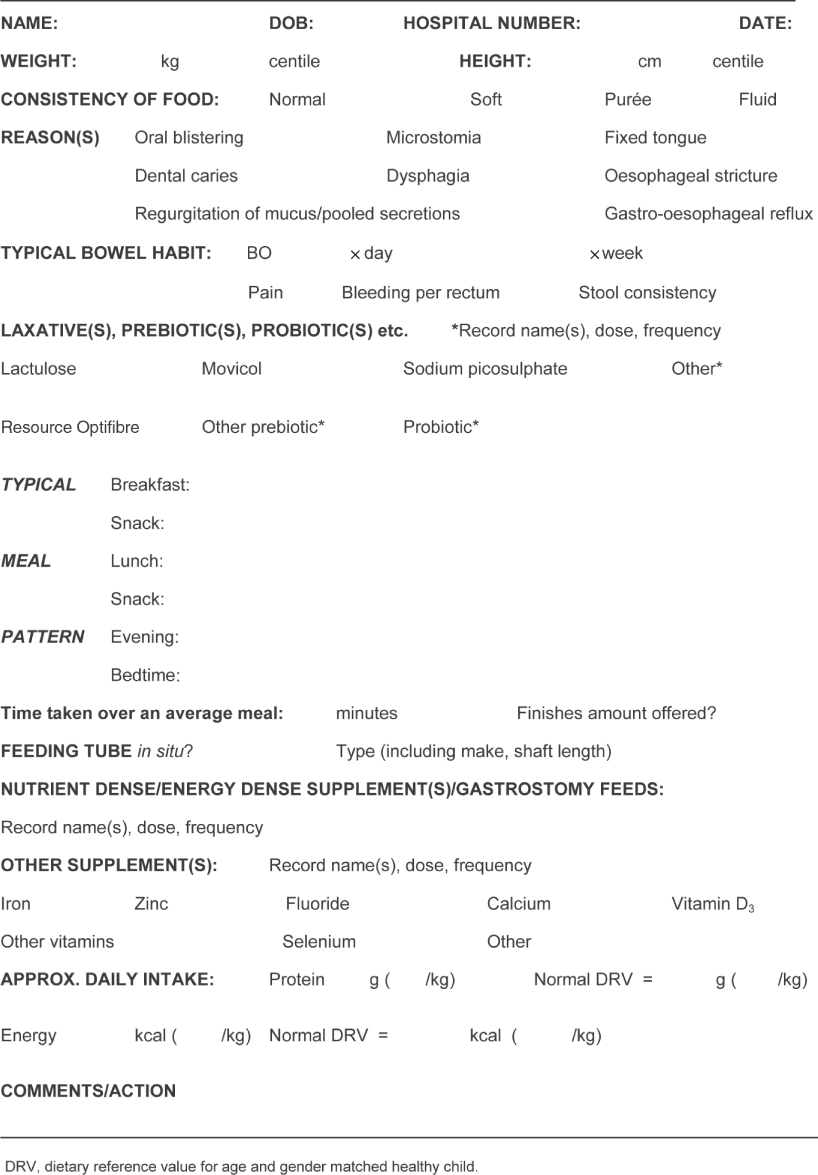

The first three types are illustrated in Fig. 24.1.

Figure 24.1 Schematic representation of the dermal-epidermal basement membrane zone. This shows the position of specific structural proteins relevant to EB. Image reprinted with permission from Medscape.com, 2012. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1062939-overview.

The classification of each EB type and subtype is based on genotype, phenotype and mode of inheritance. All types result from genetic mutations which cause a defect in, or absence of, a structural protein in the dermal–epidermal basement membrane zone or, in the case of suprabasal EBS, between adjacent keratinocytes. The resultant defective adhesion means that minor knocks or friction can cause the skin to blister. Currently, 14 different genes encoding these proteins have been implicated in different types of EB. In many instances, the exact nature of a mutation and its position on the gene will determine the phenotypic characteristics. Mutations are identified by screening the child’s DNA. This helps to confirm the diagnosis, may be useful for genotype–phenotype correlation and may determine the mode of inheritance.

Mode of inheritance

EB is usually inherited either dominantly or recessively; it may also result from a spontaneous genetic mutation with no previous family history [2]. In dominant inheritance, the affected parent (who has EB) passes on the faulty gene to their child. There is a 1 in 2 chance with each pregnancy that a child will inherit the affected gene. The more severe forms, where each parent carries the affected gene (but does not have EB), are generally recessively inherited. In each pregnancy with two carrier parents, there is a 1 in 4 chance of an affected child being conceived.

Diagnosis

A history is taken and physical examination performed; this may be followed by a skin biopsy. Non molecular techniques that are used to examine the skin biopsy include

- immunofluorescence microscopy and antigen mapping – these determine the expression of different EB associated proteins in the skin and the level of blistering by the use of antibodies [3]

- transmission electron microscopy – this determines the level of blistering and other ultrastructural clues to aid diagnosis. This is the gold standard for EB diagnosis; however, it requires great expertise and special equipment which many laboratories worldwide lack [4]

Prevalence

Prevalence is difficult to assess as mild cases may go undiagnosed, while the severely affected may die before a diagnosis is confirmed. In the UK, prevalence of all types of EB and all ages in late 2010 was estimated at 15 per million of the population [5]. EB affects the sexes equally and occurs in all races. The consequences of different EB types vary greatly in their impact, ranging from death in infancy to relatively minor handicap with normal life expectancy. Mental development is normal.

Management

Some types of EB remain the most physically disabling and disfiguring of all diseases and nutritional status is severely compromised (Table 24.1). These include RDEB, HJEB and the Dowling-Meara subtype of EBS where nutritional intervention is generally required from birth. There is currently no cure for any type of EB. A claim that one can be effected by giving an exclusion diet combined with topical and systemic treatments (the Kozak regimen) was disproved in an open evaluation [6]. Management is geared towards supportive care and prevention, or minimisation, of complications where possible. This includes control of infection, wound management, pain relief, promotion of optimal nutritional status, surgical intervention and provision of best possible quality of life (QoL) [7]. These should be addressed in a multidisciplinary team setting.

Table 24.1 Main complications influencing nutritional status and suggested interventions in some of the main types of EB

| EB type | Complications | Suggested nutritional intervention |

| RDEB Severe Generalised | Recurrent moderate to severe generalised lesions which heal poorly with scarring and contractures (causing digits to fuse). Internal contractures cause microstomia, dysphagia and oesophageal strictures. Other complications include osteoporosis/osteopenia, refractory anaemia, anal fissures, constipation, bowel inflammation/colitis and pubertal delay. Dental caries common | Increased requirements of energy and protein. Supplementation of certain micronutrients may be indicated including vitamins C and D, zinc, calcium and iron. Gastrostomy tube feeding often indicated. Specialised formula feeds and exclusion diets have been used experimentally in patients with suspected bowel inflammation/colitis with mixed results |

| DDEB Generalised | Usually mild lesions with minimal scarring. Anal fissures may cause painful and reluctant defaecation with/without constipation | Intervention is not generally indicated other than advice on healthy eating and age appropriate increases in fibre and fluid intakes if defaecation painful |

| NHJEB Generalised | Recurrent mild to severe lesions heal without scarring, but often very slowly. May be genito-urinary involvement | As for RDEB, if severe |

| HJEB | Recurrent moderate to severe and widespread lesions. Dental pain due to abnormal tooth composition. Laryngeal and respiratory complications. Initial weight gain usually followed by profound, intractable growth failure, possible protein losing enteropathy and diarrhoea. Death usually within first year or two of life | Maintain hydration, feed to appetite, address deficiencies within terminal care framework. Experimentally, minimal fat diet with medium chain triglycerides has been used. Gastrostomy placement not recommended as laryngeal/respiratory issues greatly complicate general anaesthesia and healing around exit site is very poor. Regular weighing to be undertaken only to determine best regimen for pain relief. Emphasis to be placed on quality of life |

| EBS Dowling–Meara | Wide range of severity in this type of EB. Feeding difficulties often severe in infancy including gastro-oesophageal reflux and oropharyngeal blistering. Problems generally lessen in late infancy/early childhood. Catch-up growth often occurs around adolescence. Sedentary lifestyle during adolescence tends to promote overweight as blistering becomes more confined to hands and feet. Anal fissures frequently cause painful defaecation with/without constipation | As for RDEB in early years, but gastrostomy placement is rarely necessary. Fibre, iron, zinc and vitamin supplementation may be indicated. Advice on healthy eating and weight maintenance/reduction may be indicated |

| EBS–Localised | Lesions usually confined to hands and feet, especially in hot weather, often severely limiting mobility. Frequently painful defaecation with/without constipation | Intervention is generally not indicated other than advice on healthy eating and age appropriate increases in fibre and fluid intakes if defaecation painful. Due to compromised mobility, advice on weight maintenance/reduction may be indicated |

| Kindler syndrome | Photosensitivity. Thin papery skin with variable tendency to develop lesions which predominantly affect limbs and fingers (which may fuse). May also be involvement of oesophageal, laryngeal, urethral and anal mucosa. Colitis has been documented. Gingival fragility and inflammation with poor dentition. Blistering tendency may lessen around adolescence | Intervention not generally indicated unless growth falters and/or gastrointestinal complications necessitate relevant management |

EB, epidermolysis bullosa; RDEB, recessive dystrophic EB; DDEB, dominant dystrophic EB; NHJEB, non Herlitz junctional EB; HJEB, Herlitz junctional EB; EBS, EB simplex.

Research is currently under way into new therapies which provide longer lasting improvement in patients’ conditions and, ultimately, a cure. These include [8]

- therapies which target local healing such as grafting with genetically corrected skin or injections into the skin of collagen or fibroblasts

- systemic therapies aimed at whole body healing using intravenous (IV) injections of bone marrow or other stem cells

Whilst some interventions aim for temporary improvement (collagen or fibroblast therapy) others aim for a permanent cure (grafting with genetically corrected skin or bone marrow transplant).

Nutrition support

Current practice relies on retrospective studies of small numbers of children, expert clinical experience and extrapolation from other conditions affecting the skin such as burns and pressure ulcers. Published work suggests that early, proactive intervention has the best chance of optimising nutritional status, wellbeing and wound healing in the longer term [9–12].

Breastfeeding should always be encouraged; however, rooting at the breast may cause or exacerbate facial lesions and suckling may lead to blistering of the mouth, tongue and gums. This can be eased by applying white soft paraffin (white petroleum jelly) to the lips and to the nipple to reduce friction. Except in mild cases, breast milk alone fails to meet increased nutritional requirements and it should be supplemented with standard age appropriate infant formulas either mixed with expressed breast milk (EBM) (p. 17) or given in addition to direct breast feeding. Alternatively, if formula feeding, the nutrient density of a standard age appropriate formula can be increased by concentrating the feed, or a proprietary formula with increased nutrient density can be used (Table 1.18). It is essential that any feed modifications and their rationale are explained to parents and community medical and nursing personnel to avoid misunderstandings and conflicting advice.

Feeding teats should be moistened with cooled, boiled water before feeding to avoid the teat sticking to the lips and causing damage when it is removed. A specialised teat and bottle such as the Special Needs Feeder (www.medela.com) is extremely useful as it minimises trauma to the gum margin and its internal valve and long shaft allow the carer to control the flow of feed so that even a weak suck will deliver a satisfactory milk flow. Alternatively, the hole in a conventional teat can be enlarged using a sterile needle. Care is required to ensure that the hole is not so large that milk flow causes gagging and possible feed aspiration. Babies who cannot suck may need to be fed from a spoon or dropper, but this is time consuming for regular use.

Weaning foods can be offered at the usual time of around 6 months of age using a shallow soft plastic spoon with rounded edges. Carers will need continual reassurance if progression to solids is slow and babies with an extremely fragile mouth may feed more confidently from the carer’s fingertip. Reluctance to try new foods is often due to previously, or ongoing, poorly controlled gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) [13], a very fragile painful mouth or previous nasogastric tube feeding. Scarring and tongue tethering can cause an uncoordinated swallow with the risk of aspiration [14].

There is often early aversion to food composed of mixed textures (such as the soft lumps within a more liquid matrix found in many commercial baby foods) whereas uniform textures tend to be accepted with more confidence. Hard or sharp foods such as baked rusks or crisp bread crusts are unsuitable as they damage the fragile mucosa of the mouth and gums. Although there is no evidence to suggest that long term adherence to puréed or very soft foods necessarily influences the course of dysphagia and oesophageal strictures, babies who demonstrate swallowing problems from early on may be best to remain indefinitely on such textures. The expertise of a speech and language therapist is invaluable in recommending appropriate feeding utensils and promoting confidence in feeding. Practical information for carers and community personnel can be found in the booklets Nutrition for Babies with Epidermolysis Bullosa and Nutrition in Epidermolysis Bullosa, for Children over 1 Year of Age published by the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association (DEBRA) and downloadable from www.debra.org.uk/publications.

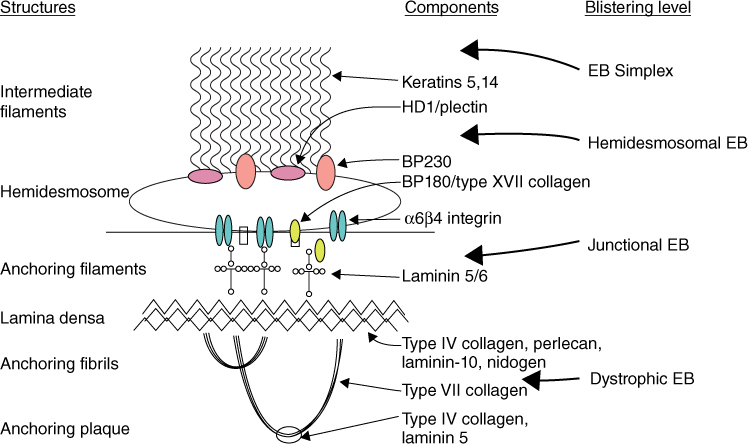

The complications of RDEB in particular begin in infancy and, except in mild cases, progressively increase as the child gets older [11, 15]. The causes and effects of severe generalised RDEB on nutritional intake are shown in Fig. 24.2. Factors such as painful defaecation (with or without constipation), extensive non healing lesions, chronic infections, general skin and bone pain, anaemia, malaise and refusal of oral medications and supplements all contribute significantly to the potential for profound nutritional compromise.

Figure 24.2 Causes and effects of nutritional problems in severe generalised recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

Nasogastric tube feeding

Despite taking great care, nasogastric (NG) tubes can cause external and internal trauma and should not be placed routinely. Externally, NG tubes should be secured with only non adhesive dressings or silicone tapes that are recommended for fragile skin. Internally, NG tubes may cause damage to the nasal tissues. In addition, they may traumatise or scar the pharynx and oesophagus interfering with oral feeding and compromising a safe swallow. Circumstances in which NG feeding may be indicated as a temporary measure include when

- a baby’s mouth becomes excessively traumatised by suckling

- satisfactory volumes of oral nutrition are not taken at any age

- gastrostomy placement is considered appropriate but evidence of the effects of improved nutrition are needed before surgery can be agreed

A 4–6 week period of NG feeding should be sufficient to show benefit.

Gastrostomy tube feeding

Publications documenting gastrostomy tube feeding (GTF) describe differing outcomes. While it has been associated with minimal complications and improved growth and bowel function, it has also been linked to pain; intractable leakage; infection and excoriation around the gastrostomy tube (G tube) insertion site; gastrointestinal (GI) problems such as severe abdominal bloating, diarrhoea, colitis, feed and food intolerance, worsening of GOR disease; abnormal body composition and central obesity [16–23]. However, in all cases, parents have expressed great relief in the stresses surrounding feeding and administration of supplements and medications, highlighting the value of GTF as a management choice and the importance of determining best practice.

The reasons for conflicting outcomes are currently unidentified, but several potential factors have been suggested including malnourished state when placement is delayed; constipation; GOR; poor placement technique of G tube and its aftercare; chronic inflammation; polypharmacy [19]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are thought to play a critical role in GI complications and the central obesity, increased fat mass and poor linear growth seen in some G tube fed children with EB [22]. After G tube placement some children develop an aversion to oral intake, preferring to rely almost entirely on gastrostomy feeds. This may reflect previous long term negativity about eating and relief at having an alternative route for nutrition. The general consensus is for G tube placement to be undertaken before complications allow malnutrition and growth retardation, with their many sequelae, to become established. With early intervention, the child is more likely to continue with oral nutrition, albeit in small and varying amounts. This is important in relation to the potential to minimise volumes of feed given overnight which impacts on tolerance of feed volumes and the need to pass urine during the night, as well as the social aspects of eating.

Oesophageal stricturing is a major reason for reduced food intake in RDEB and oesophageal dilatation (OD), singly or in series, can ease dysphagia. However, OD cannot guarantee a sufficiently increased oral intake to reverse nutritional deficits and promote catch-up growth so is not a substitute for GTF. Further work is needed to identify best practice in GTF (probably in tandem with OD) as these are currently the only practical interventions available to address nutritional compromise in the longer term [19].

Various methods of G tube placement in EB are used including open surgical gastrostomy, laparoscopically assisted endoscopy, modified laparoscopic gastrostomy and endoscopic and non-endoscopic percutaneous gastrostomy [22, 23].

The tube may be replaced by a low profile device 10–12 weeks postoperatively [23]. It is important that all internal securing material is soft or deflatable to minimise local irritation or damage to the fragile tract during change or removal. The device must be neither too loose nor too tight and the site measured each time it is changed to ensure a continuing good fit. Local policies vary regarding whether the device should be rotated. G tube feeds are generally begun within 4–6 hours of surgery, initially using sterile water, to ensure absence of leakage; discharge is usually within 48–72 hours (personal communications).

In children with impaired gastric emptying, intractable GOR or feed aspiration it may be advantageous to feed lower into the gut via a gastrojejunal or jejunal tube. As with any other child, this has implications for the rate at which feeds can be given, their volume and composition (Table 3.4).

Parenteral nutrition

Parenteral nutrition (PN) has been used in EB children with profound malnutrition or when oral intake has been severely limited by painful oral ulceration [18]. However, indwelling intravenous lines pose significant risks of septicaemia which limits their usefulness; therefore PN should be reserved for cases refractory to enteral feeding [24].

Nutritional assessment

Measurements of weight and height velocity are currently the most practical means of assessing growth. Weight and if possible height (length) should be measured regularly. Downward deviation from the birthweight centile in the first year is common in severe types of EB despite proactive nutritional interventions.

Weight measurements should ideally be performed directly after a dressing change as wound exudates in the dressings could lead to overestimation. Although nude weight is ideal, the skin damage incurred during handling usually precludes this.

Due to pain and contractures around joints, height measurements are impractical in severely affected children. A supine stadiometer or measuring mat may provide greater accuracy. If neither of these is possible, segmental measurements using specialised calipers or a metal tape may be used [11].

Other anthropometric measurements are difficult to perform as dressings impede access to desired areas and measuring instruments may damage the skin.

Despite proactive nutritional intervention, growth retardation often occurs early in the course of severe EB [20, 21]. Since complications increase in number and severity over time, it is difficult to judge whether growth and overall nutritional status are optimal. The traditional ‘rule-of-thumb’ that disparity between weight and height should not be greater than two major centiles is generally applicable. Although body mass index (BMI) does not differentiate between lean and fat tissue, data from a centre with good outcomes following G tube placement suggests it as a reliable means to monitor growth and predict optimal timing for placement [25].

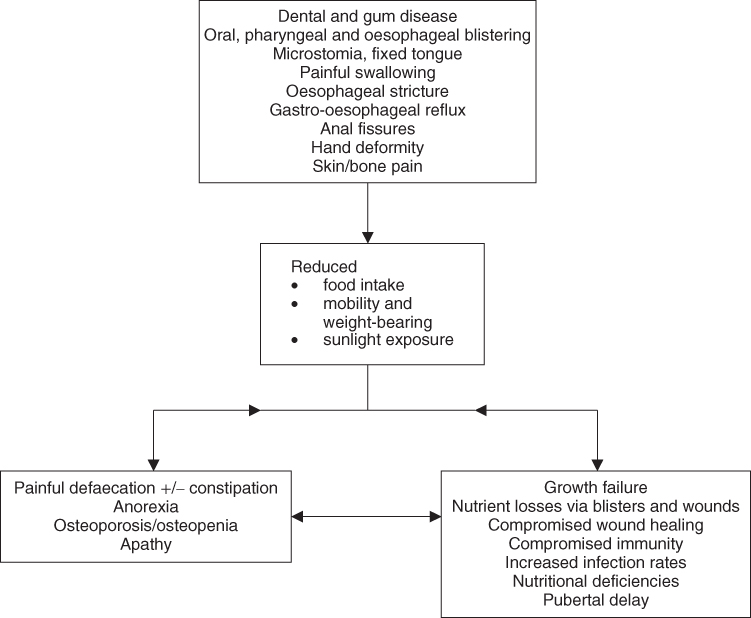

Regular nutritional assessment (Table 24.2) is important not only to address ongoing problems but also to anticipate them. The proforma in Table 24.2 can be used to record relevant information.

THINC, a Tool to Help Identify Nutritional Compromise (currently unvalidated), has been developed as a comprehensive method of assessing the risk of actual or potential nutritional compromise in EB children under and over 18 months of age and forms part of nutrition clinical practice guidelines written for EB [26]. It has been developed to aid, not replace, clinical judgement and its scoring charts rate the three key aspects of the child’s state: weight and height; gastroenterology and feeding; dermatology. The higher the score, the greater is the likelihood of nutritional compromise. According to the total nutritional compromise score, algorithms suggest varying courses of action.

Biochemistry and haematology

Interpretation of laboratory results in EB children is difficult because of the inflammatory nature of the condition. Table 24.3 [27] lists investigations that should be carried out with suggested sampling intervals. Frequency depends on disease severity, the need to evaluate an intervention or to modify management.

Table 24.3 Laboratory investigations

| Investigation | Suggested sampling intervals |

| Urea and electrolytes: Sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine | 6 monthly unless abnormal |

| Liver function tests: Total bilirubin, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase | 6 monthly |

| Bone profile: Calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase, vitamin D | 6 monthly |

| Trace elements: Zinc, selenium, vitamin B12, vitamin A, vitamin C, folic acid | Annually |

| Iron studies: Total iron binding capacity Serum iron Ferritin | 3–6 monthly depending on degree of anaemia and if having iron infusions |

| Full blood count (FBC) | 3–6 monthly depending on degree of anaemia |

| Red cell folate | Annually |

Nutritional requirements

Two main factors potentially compromise nutritional status in EB:

- the hypercatabolic state in which open skin lesions with consequent losses of blood and serous fluid, increased protein turnover, heat loss and infection all contribute to increased requirements

- the degree to which oral, oropharyngeal, oesophageal and GI complications limit intake

It is difficult to quantify nutritional requirements due to [11]

- the diversity of disease severity of patients even with the same EB type

- the variability over time of individual patients’ requirements

- the difficulties associated with estimating desirable weight gain when height is compromised

- the location and presence of infection which complicates the interpretation of laboratory results

- the chronic inflammatory nature of EB characterised by continued expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [19]

Energy

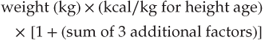

Energy requirements can be estimated using the following formula [15]:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree