The link between smoking and development of lung cancer has been demonstrated, not only for smokers but also for those exposed to secondhand smoke. Despite the obvious carcinogenic effects of tobacco smoking, not all smokers develop lung cancer, and conversely some nonsmokers can develop lung cancer in the absence of other environmental risk factors. A multitude of genetic factors are beginning to be explored that interact with environmental exposure to alter the risk of developing this deadly disease. By more fully appreciating the complex interrelationship between genetics and other risks the development of lung cancer can be more completely understood.

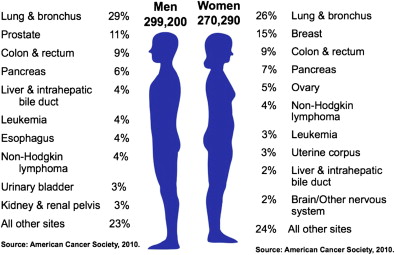

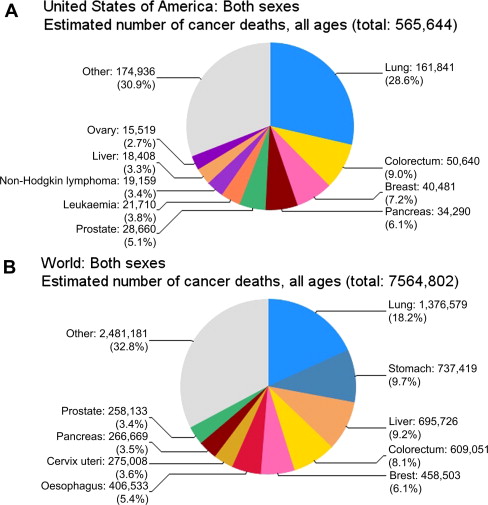

The cause of lung cancer is multifactorial with genetic risk and lifestyle and environmental exposure risks. The rates of lung cancer globally have been changing, and continue to change, remarkably over the past 100 years. Lung cancer is currently the leading cause of cancer death in men and women ( Fig. 1 ), accounting for more than 157,300 deaths in the United States during 2010, and more than 1.3 million deaths worldwide ( Fig. 2 ). The rise of the lung cancer epidemic over the past 100 years correlates with the increased acceptance of smoking tobacco and the commercialization and mass production of tobacco during the same time period. Despite the known and proved carcinogenic risk of tobacco exposure, most lifelong smokers do not develop lung cancer, and conversely there are infrequent lifelong never-smokers who develop lung cancer in the absence of identifiable carcinogenic exposure. The complex interrelationships between smoking, other environmental carcinogens, and genetic risk are becoming better defined and have been shown to have synergistic, not simply additive impact on the development of lung cancer. By evaluating and understanding these relationships, future efforts at identifying high-risk individuals may lead to earlier detection, and by appreciating the risk of secondhand smoke and other environmental carcinogens, future efforts to reduce exposure may gain support in the battle against this deadly disease.

Historical perspective of smoking

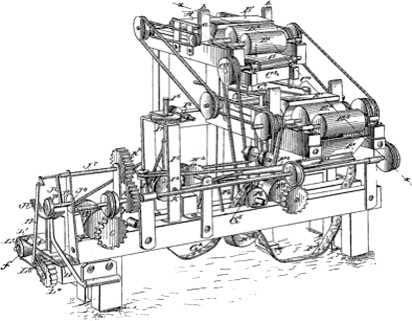

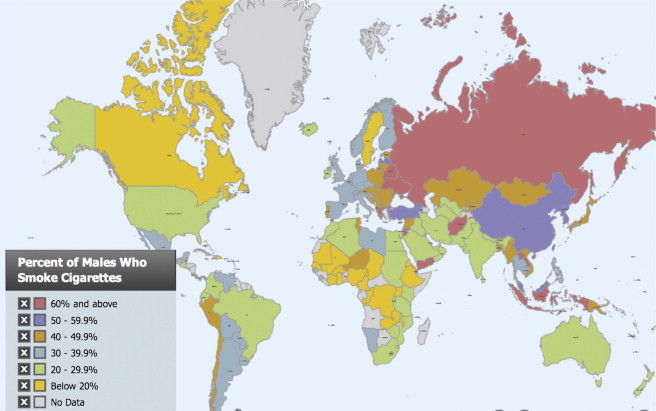

The tobacco plant is native to the Americas, and before the European discovery of the Americas, tobacco was unknown in the rest of the world. After Europeans were introduced to tobacco and nicotine addiction, tobacco use grew in popularity, but much of tobacco use was in the form of chew tobacco, pipe tobacco, cigars, or snuff. Cigars and pipe tobacco produce smoke that is highly alkaline, of relatively large particle size, and irritating to the airways, and thus usually lead to buccal and pharyngeal absorption rather than pulmonary alveolar exposure. In the 1800s cigarettes were handmade and not common. The Bonsack machine ( Fig. 3 ), patented in 1881, which could roll 12,000 cigarettes per hour, revolutionized the efficiency of the tobacco industry and led to a rise in the cheap accessibility of the cigarette after 1900. Cigarettes are often smoked with deeper inhalation and greater exposure of the lung to nicotine and carcinogens. Modern engineering of the cigarette has included the addition of anti-irritants, such as menthol and other chemicals, to allow deeper inhalation of nicotine and carcinogens to the lung parenchyma. The deep inhalation of nicotine from a cigarette provides a rapid rise and peak in nicotine levels to the brain within seconds. This is a much more rapid rise and peak than that from chew tobacco or pipe tobacco, in which the nicotine is slowly absorbed via buccal and pharyngeal mucosal surfaces. The cigarette not only is an extremely efficient nicotine delivery device, but the rapidity of the delivery leads to a much more addictive form of tobacco use. Today, with globalization of farming, manufacturing, marketing, and shipping, tobacco use is prevalent in nearly every society across the globe with most industrialized societies reporting at least a 20% smoking rate, and some countries (eg, Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus) reporting a 60% to 70% smoking rate among men, and an 82% rate of men in Afghanistan ( Fig. 4 ). It is unsurprising that the rates of lung cancer reflect this, and are significantly higher in geographic areas with a higher rate of smoking. In addition, over the past 100 years changes in public health, such as air and water quality improvements, sanitation, immunization, and antibiotics, have led to a longer lifespan in industrialized nations. Lung cancer most often arises after decades of carcinogen exposure, with the average lung cancer patient more than 65 years old at time of diagnosis. The complex combination of rapidly rising widespread cigarette use and improvements in other areas of public health has led to a large population of individuals exposed to decades of carcinogen exposure who live long enough, in turn, to develop lung cancer.

Historical perspective: changes in the smoking epidemic

As a junior medical student, Alton Ochsner and his class were summoned to witness an autopsy of a patient who had died of a rare disease: primary lung carcinoma. The year was 1919, and indeed it was rare at the time; he did not witness another case for the next several years, even as a thoracic surgeon. Seventeen years later, he witnessed eight cases in a 6-month time span. He noted many of these patients were male veterans of World War I who had a history of smoking. It is now well accepted that tobacco smoke leads to multiple diseases including lung cancer, but this was not common knowledge nor accepted at the time. His report with DeBakey in 1939 was one of the first to suggest a link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer, yet his views were not widely accepted nor respected. At one point when Ochsner, as a faculty member, entered a classroom of medical students to deliver a lecture, the entire class intentionally lit up cigarettes. Cigarette smoking continued to rise in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s, despite significant epidemiologic observational studies linking tobacco and lung cancer. In 1964, Surgeon General Luther L. Terry released a groundbreaking 387-page report “Smoking and Health.” Terry and his advisory committee had compiled data from thousands of articles concluding that cigarette smoking was indeed a cause of lung cancer in men, and likely a cause of lung cancer in women. At the time 46% of adults in the United States were active smokers. Since the Surgeon General’s report, multiple factors have led to a decline in the smoking rate in the United States, including but not limited to restriction on sales to minors, advertising restrictions, increased taxation, warning labels, and increasing bans on smoking in public areas. Further research has led to reinforced evidence of the link between smoking and lung cancer and development of nonneoplastic diseases, such as chronic bronchitis, emphysema, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease. Despite oceans of evidence of the negative impact of smoking, and increasing limitations and taxation, approximately 20% of the current adult United States population continues to smoke.

Historical perspective: changes in the smoking epidemic

As a junior medical student, Alton Ochsner and his class were summoned to witness an autopsy of a patient who had died of a rare disease: primary lung carcinoma. The year was 1919, and indeed it was rare at the time; he did not witness another case for the next several years, even as a thoracic surgeon. Seventeen years later, he witnessed eight cases in a 6-month time span. He noted many of these patients were male veterans of World War I who had a history of smoking. It is now well accepted that tobacco smoke leads to multiple diseases including lung cancer, but this was not common knowledge nor accepted at the time. His report with DeBakey in 1939 was one of the first to suggest a link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer, yet his views were not widely accepted nor respected. At one point when Ochsner, as a faculty member, entered a classroom of medical students to deliver a lecture, the entire class intentionally lit up cigarettes. Cigarette smoking continued to rise in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s, despite significant epidemiologic observational studies linking tobacco and lung cancer. In 1964, Surgeon General Luther L. Terry released a groundbreaking 387-page report “Smoking and Health.” Terry and his advisory committee had compiled data from thousands of articles concluding that cigarette smoking was indeed a cause of lung cancer in men, and likely a cause of lung cancer in women. At the time 46% of adults in the United States were active smokers. Since the Surgeon General’s report, multiple factors have led to a decline in the smoking rate in the United States, including but not limited to restriction on sales to minors, advertising restrictions, increased taxation, warning labels, and increasing bans on smoking in public areas. Further research has led to reinforced evidence of the link between smoking and lung cancer and development of nonneoplastic diseases, such as chronic bronchitis, emphysema, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease. Despite oceans of evidence of the negative impact of smoking, and increasing limitations and taxation, approximately 20% of the current adult United States population continues to smoke.

Changes in lung cancer rates over time

In 1919, when Ochsner was a medical student, the death rate from lung cancer was less than 5 per 100,000, and rose throughout the next 65 to 70 years. It was not until the early 1990s that the lung cancer death rate reached a plateau at more than 90 per 100,000 and subsequently began to decline for men ( Fig. 5 A). The lung cancer death rate for women, however, continued to rise through the 1990s, and seems to be currently reaching its plateau at approximately 40 per 100,000 (see Fig. 5 B). The United States has the highest rate of lung cancer for women of any country in the world with approximately 43.2 deaths per 100,000. The number of deaths in the lung cancer epidemic is appalling, especially when one considers the perspective that lung cancer takes more lives than breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers combined, and that most lung cancer deaths are preventable. Unfortunately, lung cancer is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, in older individuals who often harbor additional comorbidities, rendering most patients with lung cancer unresectable and incurable. The 5-year survival rate for all patients with lung cancer in the United States is a mere 16%, and this has only changed slightly from a 13% survival rate noted from 1975 to 1977. Over the past 30 years the survival rates for breast cancer have improved from 75% to 90% because of many advances including screening, surgical treatment, and medical treatment including hormonal therapy. Colon cancer 5-year survival rates have also improved from 52% to 66% during this same interim ( Fig. 6 ). Despite advances in many aspects of medical care, lung cancer cures remain elusive. Therefore, the greatest potential for impact on reducing the number of lung cancer deaths on an epidemiologic level seems to be with control of risk and prevention rather than advances in treatment of this deadly disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree