Approximately 29,620 men and 11,760 women in the United States are diagnosed each year with cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx.

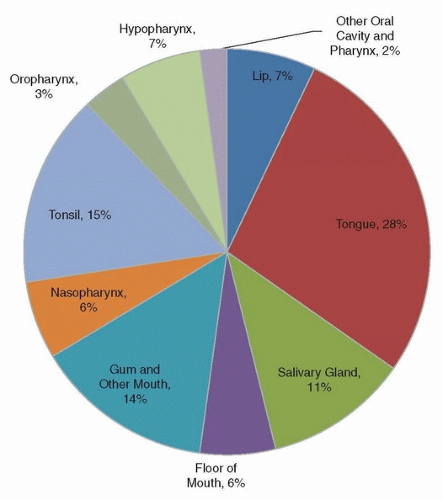

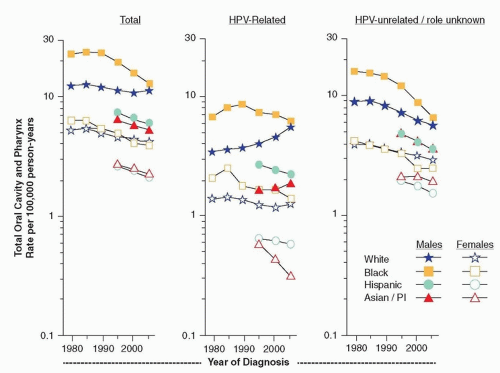

1 Cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx (OCPC) includes several subsites: lip, tongue, salivary glands, floor of the mouth, gum and other mouth, nasopharynx, tonsil, oropharynx, hypopharynx and other oral cavity, and pharynx. Other oral cavity and pharynx cancers include Waldeyer ring, overlapping lesions of lip, oral cavity, and oropharynx as well as not otherwise specified (NOS) cancers. As shown in

Figure 4.1, the most common type of OCPC is cancer of the tongue (28%), followed by tonsil (15%) and gum and other mouth (14%). Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common cancer (82%) of OCPCs. Other less common histopathologies include adenocarcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, as well as ductal and lobular cancers.

2

Risk Factors

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified smoking tobacco as a cause of cancer of the oral cavity.

3 Studies have consistently shown an increased risk of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx among smokers.

4,5,6,7,8,9 Case-control studies have reported up to 11 to 12 times risk of OCPC among current smokers compared to never smokers,

4,5 and the risk of OCPC increases with amount and duration of smoking.

6,7,8,9 In addition, the synergistic effect of alcohol on smoking has been established in several studies.

6,7,10 For example, among never drinkers, the odds of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer are 1.7 to 1.9 higher for cigarette smokers,

and for heavy drinkers, these odds are 9.60 to 11.37 higher.

6 There is some heterogeneity in the effect of cigarette smoking by OCPC subsite as tobacco exposure is found to be more strongly associated with cancers of the soft palate than other sites.

11 Additionally, the use of black versus blond tobacco may have an even greater risk of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer.

12 Among former smokers, the risk of cancer of the oral cavity is less than that of smokers, and one study reported that after 10 years of quitting, former smokers had the same risk of OCPC as never smokers.

9,13Several forms of smokeless tobacco are associated with cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx. Smokeless tobacco in the form of snuff, which is found most commonly in the United States, is independently associated with cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx in US studies.

14 However, studies of smokeless tobacco in Sweden and Norway, where moist snuff or snus is more common, have not reported increased odds of oral or pharyngeal cancer.

15,16 Another form of chewing product called betel quid used in Asia that may or may not contain tobacco, is also associated with OCPC. IARC concluded that betel quid with tobacco causes cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx, whereas betel quid without tobacco causes cancer of the oral cavity only.

17,18Not only does alcohol interact with tobacco to increase the risk of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx, but also there is an independent contribution of alcohol on OCPC.

16,19,20 Among nonsmokers, the risk of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx is elevated among alcohol drinkers compared to nondrinkers.

21,22 A dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx has also been observed as heavy drinkers have a particularly high risk of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx.

10,16,19,21 A meta-analysis found a 4.6- and 6.6-fold increase in odds of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx among heavy drinkers compared to never

drinkers, respectively.

23 Some studies have suggested variations in the effect of alcohol by subsite; however, the pattern is inconsistent across studies.

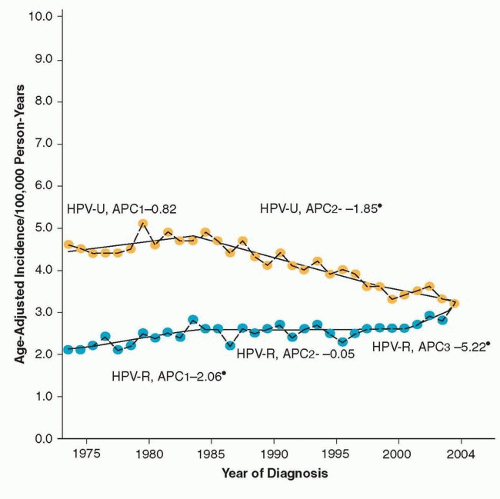

10,12,24Although historically, cancers of the oral cavity and oropharynx have been attributed to tobacco and alcohol, in recent years, an increasing number of cases of squamous cell carcinoma, particularly those in the oropharynx, have been associated with HPV infection. Several case-control studies have demonstrated an association between HPV and the risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, independent of tobacco and alcohol use.

25,26,27,28 A multicenter case-control study containing 1,670 cases and 1,732 controls from nine countries reported a positive association between HPV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) positivity in oral biopsies and oropharyngeal cancer (OR 4.9, 95% CI 2.6 to 9.1), after having been adjusted for demographic information as well as smoking and alcohol intake.

26 In the same study, the association was even stronger when the presence of high-risk HPV 16 was considered.

26 A subsequent case-control study in the United States also reported a strong association between cancer of the oropharynx and HPV oral infection (adjusted OR 14.6, 95% CI 6.3 to 36.6) as well as HPV 16 E6 and E7 positivity (OR 58.4, 95% CI 24.2 to 138.3).

27HPV 16 accounts for the majority of HPV-related cancers, followed by HPV-18, and even more rare are HPVs 33, 6, and 11.

26,29,30 Case series report a wide range of HPV prevalence from 4% to 80% among oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC) and 14% to 57% among oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), which is likely due to variations in populations, risk factors, and HPV detection methods.

29 A pooled analysis of over 2,500 OCSCC cases across several continents including Asia, Europe, Australia, North America, and South America reported a 23.5% (95% CI 21.9 to 25.1) prevalence, whereas the prevalence of HPV positive among 969 OPSCC cases in this pooled analysis was higher (35.6%, 95% CI 32.6 to 38.7).

30 Though the aforementioned pooled study reported an overall higher HPV positivity among North American cases of OPSCC (47%) and OSCC (16%) than the worldwide combined estimate, other multinational studies have shown no differences in HPV prevalence among OPSCC and OSCC across continents.

26The potential synergistic effect of tobacco, alcohol, and HPV positivity is less well understood. Several investigators have studied this issue using a variety of methods including hospital- and population-based case-control studies with incidence of cancers of the head and neck, whereas some studies included only cancers of the oropharynx. A population-based study of oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer reported a higher prevalence of smoking in HPV-seropositive cancers (31.3%) compared to HPV-seronegative cancers (20.1%).

27 The finding of additive interaction for tobacco and HPV exposure has been observed in other studies as well.

26 However, a hospital-based case-control study found a similar proportion of smokers in HPV-positive (63%) and HPV-negative (67%) cases.

31 Similarly, other studies have found no interaction between HPV and smoking.

25,32Some occupational studies have found increased odds of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx among workers exposed to aromatic amines, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, solvents, and nitrosamines

33,34; however, these associations are not consistent across studies and some studies were unable to control for tobacco use. Consumption of mate, a popular infused drink in parts of Latin America, may be related to increased cancer of the oral cavity though it is not known if the increased risk is due to its hot temperature, a potential carcinogenic effect of mate, or a combination of the two.

35,36 Fruits and vegetables are protective against OCPC; a pooled analysis indicated that high vegetable consumption was associated with a 50% reduction in OCPC.

37 In contrast, individuals with diets high in meat and dairy, controlling for alcohol and tobacco consumption, are at an increased risk of cancer of the oral cavity.

38 Other factors related to oral cavity cancer include a family history as cases with a first-degree relative with cancer of the oral cavity are at an increased risk for the disease after taking into account their consumption of alcohol and tobacco.

39 Inheritable disorders, including Fanconi anemia, are also linked to cancer of the oral cavity.

40 Additional genetic mutations that may be related to oral cavity mutation include germline mutations in p16.

41