The upper gastrointestinal (UGI) system, as addressed within this chapter, is comprised of the esophagus, the stomach, and the small intestine. Anatomically, the cervical esophagus is bordered superiorly by the hypopharynx and inferiorly by the thoracic inlet. The intrathoracic esophagus extends to the diaphragmatic hiatus, from where the intra-abdominal esophagus extends to the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). The gastric cardia, identified by origin of the rugal folds, represents the highest part of the stomach, followed by fundus, body, antrum, and pylorus. Duodenum, jejunum, and ileum are the three major small bowel components. Malignant tumors even within the same part of the UGI tract may require distinct therapeutic interventions based on their location (i.e., cervical vs. lower thoracic esophagus, duodenum vs. ileum). EGJ cancer, while possibly a special entity when it comes to therapeutic decision making, lacks separate epidemiologic data and is therefore embedded, based on EGJ cancer type and the United States Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) distinction, within esophageal or gastric cancer data. In the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging from 2010, EGJ cancer stage criteria follow those of esophageal adenocarcinoma.1

According to the latest data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer, esophageal cancer is currently the eighth most common cancer worldwide and the sixth most deadly.2 Age-adjusted incidence rates (AAIR, which we will report per 100,000 population) in less developed regions were over twice those of more developed regions (8.6 vs. 3.6).2 Geographical areas with the highest AAIR were Southern Africa and Eastern Asia (16.3 and 14.2), whereas the lowest AAIR occurred in Middle and Western Africa (1.1 and 1.2, respectively). As esophageal cancer is most often diagnosed at a more advanced disease stage, the incidence-mortality ratio is high, with age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMR) of 7.3 and 2.9 in less developed regions and more developed regions, respectively.2

Esophageal cancer is a disease that occurs more often in men than in women, with worldwide AAIR of 10.1 in men compared to 4.2 in women.2 This difference is greater in more developed regions, where the incidence ratio between males and females is 5.4:1 compared to 2.1:1 in less developed regions.2 Data from the SEER program show that from 2006 to 2010, AAIR were 7.7 in men compared to 1.8 in women.3 Reasons for this sex disparity are likely related to abdominal obesity, a condition more prevalent in males than females, as well as lifestyle differences such as smoking and alcohol consumption.4,5

In the United States, the median age of esophageal cancer diagnosis is 67, with rates highest in those aged 65 to 74; less than 15% of esophageal cancer patients are under 55.3 Incidence rates in black and non-Hispanic white men are higher than those of Hispanic or Asian/Pacific Islanders (API), with AAIR at 8.4, 8.0, 5.2, and 3.9, for black, white, Hispanic, and API men, respectively.3 These differences are thought to primarily reflect lifestyle factors.6

Although data on incidence rates worldwide are of varying quality, data from GLOBOCAN 2012 show that rates in men are declining dramatically in Eastern countries, such as China, India, and Singapore.7 In Europe, incidence rates among men are declining in France and Slovakia but are increasing in England and Denmark. Rates among men in the United States, Australia, and Canada have remained stable over time. In women, similar trends are seen in Asian countries, with dramatically declining incidence rates in India, China, and Singapore. In European countries, rates are stable, even in countries where incidence rates among men are changing. In the United States, Australia, and Canada, the rates have remained stable over time.7

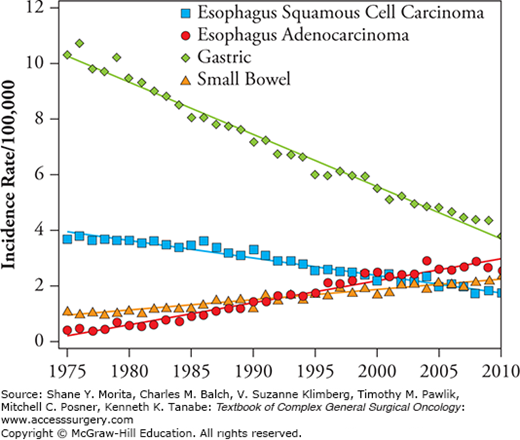

Esophageal cancer is primarily comprised of two histologic subtypes, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). These histologic types are distinct in both their etiology and tumor location. Adenocarcinomas arise from glandular cells and are more frequently located in the lower-third of the esophagus.8 SCCs, however, are associated with chronic irritation caused by tobacco smoke and heavy alcohol consumption, and are more commonly found in the upper two-thirds of the esophagus.9 Traditionally and throughout most of the world, SCC has been more prevalent than adenocarcinoma, encompassing 90% to 95% of esophageal cancer. These patterns are now shifting in areas such as the United States and Western Europe where adenocarcinomas now account for 50% to 80% of cases.9 Specifically, in the United States from 1975 to 2010, SCC AAIR dropped from 3.7 to 1.8, whereas adenocarcinoma AAIR rose from 0.4 to 2.5 (Fig. 84-1).

When developing the current esophageal cancer AJCC staging system, version 7, the Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration sought to harmonize the staging of esophageal cancer, EGJ cancer, and gastric cancer to provide continuity across sites.10,11 This resulted in two distinct sets of staging criteria for esophageal cancers, one for adenocarcinoma and another for SCC (Table 84-1). EGJ primaries, that is, tumors located within 5 cm above or below the EGJ, are included in the staging for esophageal cancer. Although AJCC version 7 staging criteria used data-driven methodologies based on worldwide retrospective data, the majority of the data on esophageal cancer came from Japan.12 Because Japan has a higher prevalence of SCC than adenocarcinoma, version 7 staging criteria have been criticized as more applicable to SCC than adenocarcinoma.13 This is particularly problematic in areas such as the United States where adenocarcinomas are now much more common than SCCs.14 In addition, the inclusion of EGJ in the adenocarcinoma staging criteria is controversial as the majority of EGJ cancers in Asia represent gastric cardia or proximal gastric cancers, whereas EGJ in Western countries predominately represent lower esophageal cancers. A prior criticism of version 6, in which abdominal nodes were considered M1 disease, was revised in version 7 to now categorize retrogastric and celiac nodes as regional.12,15

Esophageal Cancer TNM Categories and Stage Definitions, AJCC Version 7a,b

| T | Primary Tumorc |

|---|---|

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | High-grade dysplasiad |

| T1 | Tumor invades lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa |

| T1a | Tumor invades lamina propria or muscularis mucosae |

| T1b | Tumor invades submucosa |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria |

| T3 | Tumor invades adventitia |

| T4 | Tumor invades adjacent structures |

| T4a | Resectable tumor invading pleura, pericardium, or diaphragm |

| T4b | Unresectable tumor invading other adjacent structures, such as aorta, vertebral body, and trachea |

| N | Regional Lymph Nodese |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastases in 1–2 regional lymph nodes |

| N2 | Metastases in 3–6 regional lymph nodes |

| N3 | Metastases in ≥7 regional lymph nodes |

| M | Distant Metastasis |

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

Commonly cited risk factors for esophageal SCC are tobacco use, low socioeconomic status (SES), poor oral hygiene, alcohol consumption, nutritional deficiencies, and esophageal achalasia.16–21 Although Barrett’s esophagus is strongly linked with esophageal adenocarcinoma, it is not commonly associated with SCC. A decreased risk of SCC has been associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), with potentially protective effects related to the inhibition of the COX-2 pathway, which may result in a decrease in inflammation and angiogenesis.

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) and chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are the main risk factors associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma. BE is associated with a 30- to 125-fold increased risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma.22,23 A recent meta-analysis based on 57 studies estimated that the pooled incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma among patients with nondysplastic BE was 0.33%.24

Within BE cases, the distance between the gastroesophageal junction and the most proximal extent of Barrett metaplasia establishes whether there is long-segment (≥3 cm) or short-segment (<3 cm) BE. Although long-segment BE is less common than short-segment BE, the risk of adenocarcinoma increases with the length of BE, with a reported 19% increase in risk per centimeter (OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.30).25

The association between GERD and esophageal adenocarcinoma is likely related to the damage that chronic acid and bile exposure have on esophageal squamous cells. When these squamous cells are damaged, columnar epithelial cells replace them. The new metaplastic columnar epithelium that develops may be predisposed to eventual transformation to adenocarcinoma. Lagergren et al26 estimated the risk ratio of esophageal adenocarcinoma for patients who had 5 years or more of (1) heartburn, regurgitation, or both at least once a week, or (2) at night at least once a week, as 7.7 (5.3–11.4) and 10.8 (7.0–16.7), respectively.

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common and second most lethal cancer worldwide.2 IARC data show that incidence rates are higher in less developed regions compared to more developed regions (AAIR 15.2 vs. 11.4, respectively).2 The areas with the highest AAIR include Eastern Asia , specifically Korea and Japan, at 30 and Central and Eastern Europe at 14.6. Regions with the lowest AAIR are Africa and North America (range 3.0 to 4.9 and 4.2). Because most patients present with advanced disease, AAMR follow similar trends, although the AAMR are about 20% lower than AAIR.2

Like esophageal cancer, gastric cancer affects men more often than women. Both worldwide and within the United States, men are diagnosed at approximately twice the rate of women. In the United States from 2006 to 2010, the average AAIR was 10.4 in men and 5.3 in women.3 Mortality rate in men was also about twice that in women, at 4.9 compared to 2.5, respectively. In Japan, where overall the incidence and mortality rates are significantly higher than in the United States, at 31 and 14, respectively, the ratio of men is also higher at 2.6 men diagnosed or dying from gastric cancer compared to every 1 woman.2

In the United States, incidence rates vary across race/ethnicity, with AAIR highest in blacks (16.1 in men and 8.7 in women) followed by API (15.5 in men and 9.3 in women), with the lowest rates found in non-Hispanic whites (9.2 in men and 4.5 in women).3 Age-specific statistics show that incidence and mortality rates are higher in older patients, with those aged 65 to 84 representing nearly 50% of the cases.3 In 2010, median age at diagnosis was 71, with men diagnosed younger than women (70 vs. 72, p<0.002) (unpublished data, SEER 2012 data submission). In addition, AI/AN, Hispanics and Blacks are diagnosed younger than API and whites at median ages of 66, 69, 72, and 74, respectively (p<0.0001) (unpublished data, SEER 2012 data submission).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree