Epidemiology and Prognostication in Noncancer Diagnoses

Daniel L. Handel

Joyson Karakunnel

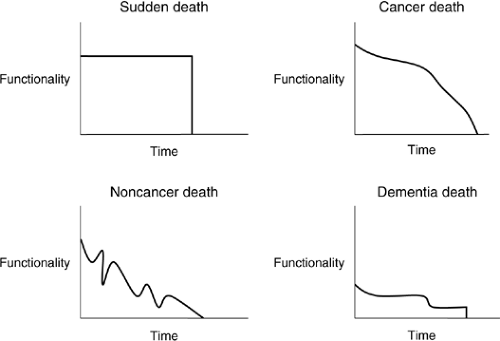

Prognostication of illness is an important part of helping health care providers in guiding treatment. Yet, the ability of health care professionals to provide this information is extremely difficult and often erroneous (1). The progression of illness has been well studied and broadly characterized by four “trajectories of an illness.” These trajectories have been characterized in functional graphs, with each of the four trajectories having the following unique properties: baseline commencement, shape, and duration (2, 3). Therefore, death can occur in the following ways:

Unexpectedly (sudden death)

Predictably following a steady functional decline (cancer)

Following a deteriorating baseline that is punctuated with health crises, each of which is followed by a partial recovery to a lower level of function (chronic illness) (2, 3, 4, 5).

Cancer’s relatively predictable functional decline can often be anticipated by the patient and the family and is well known in the hospice environment. Sudden death is by its nature unanticipated, with little opportunity for planning or anticipatory grieving. However, the family does not undergo prolonged periods of functional decline and issues brought by intermittent health crises that are common in chronic illness. In chronic illness, the gradual functional decline can be interrupted by sudden, precipitous downturns, from which the patient commonly recovers to a new and lower functional baseline. These peaks and valleys are often unpredictable and can be extremely frightening for the patient and family. This course will often end unexpectedly with a fatal event occurring during one of these valleys. The fourth and final characterization of the illness trajectory begins with a low functional level that inexorably declines to death. The function in this type of degenerative illness is chronically at a low baseline level, never recovering significantly to an improved baseline. Patients or families often endure significant suffering as functional declines dictate difficult health care decisions. The emphasis of this chapter will be on diseases that fall into the latter two categories, namely, those characterizing chronic and neurodegenerative illnesses. Chronic disease has become a growing problem in our society as treatment options expand and people survive longer with serious illness. Many of these illnesses are chronic and debilitating. Stroke is the number three killer in the United States, with an incidence of more than 700,000 strokes per year, making stroke the leading cause of debilitating disease in the United States (7). Cardiovascular disease accounts for 1 in 2.6 deaths in the United States (7). Together, these diseases account for most hospitalizations in the United States (7). The economic burden is also overwhelming to society (7). The incurability of many of these illnesses makes recovery from the diseases very unlikely. In fact, the “trajectory of illness” for these illnesses demonstrates that patients have a slow decline with little or no overall improvement before the fatal event.

Health care providers try to accurately predict the course of these illnesses. Prognostication is an important tool used by health care providers. It helps provide information for families and patients on the likely course of illness and guidance in establishing reasonable goals of care. The establishment of a likely course of the illness and goals of care facilitates informed decision making about potential treatments and interventions. In addition, good prognostication can help guide the critically important process of determining hospice appropriateness and eligibility. The decision to pursue hospice can benefit not only the patient but also society. Patients with chronic illnesses, as mentioned previously, are faced with repeated decisions regarding hospitalizations and treatments that fail to improve function or meaningfully impact medical outcomes. Prognostication and appropriate medical decision making can help alleviate the societal and personal burdens resulting from futile medical treatments.

Yet, health care providers should use caution when evaluating data that is available from several different studies (8) (Table 43.1). The limitations of these predictions are factors that hinder a provider’s ability to determine the appropriate counsel and therapy at any given point in the illness. Regardless of the setting or illness, these clinical predictions are not uniformly effective (1, 9, 10). In addition, health care workers often give more optimistic predictions than warranted by the data (11). But there are several prognostic tools that can help in patient evaluations: the Karnofsky Performance Status Scale (KPS) (12, 13). (Table 43.2), the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification (14), the Functional Assessment Staging (FAST) scale (which can be used for a variety of symptoms) (15), and the index of activities of daily living (ADL) (16). For noncancerous illnesses, the best prognostic factors tend to be either disease-specific factors

such as arterial blood gas levels and left-ventricular function in congestive heart failure (CHF) or global functional indicators (6-minute walk test or quality of life indicators) (17, 18). The Medicare/Medicaid Hospice Benefit provides both general and disease-specific guidelines for patients who are referred to hospice. The Medical Guidelines for Determining Prognosis in Selected Non-Cancer Disease (19) is organized to provide general, functional indicators to assist in the assessment for hospice eligibility, coupled with specific, disease-specific guidelines that apply to particular diseases. Excerpts from these guidelines will be shared throughout this chapter to detail some important considerations in evaluating the needs and hospice appropriateness of specific conditions. It should be noted that these are not rules but rather guidelines to assist the health care provider in determining hospice eligibility. General guidelines are listed in Table 43.3.

such as arterial blood gas levels and left-ventricular function in congestive heart failure (CHF) or global functional indicators (6-minute walk test or quality of life indicators) (17, 18). The Medicare/Medicaid Hospice Benefit provides both general and disease-specific guidelines for patients who are referred to hospice. The Medical Guidelines for Determining Prognosis in Selected Non-Cancer Disease (19) is organized to provide general, functional indicators to assist in the assessment for hospice eligibility, coupled with specific, disease-specific guidelines that apply to particular diseases. Excerpts from these guidelines will be shared throughout this chapter to detail some important considerations in evaluating the needs and hospice appropriateness of specific conditions. It should be noted that these are not rules but rather guidelines to assist the health care provider in determining hospice eligibility. General guidelines are listed in Table 43.3.

Table 43.1 Limitations of Prognosis Studies | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Table 43.2 Karnofsky Performance Status Scale | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 43.3 Medicare Hospice Guidelines—General Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

In palliative medicine, prognosis is mainly used to guide decision making and to facilitate preparation for anticipated changes. It is also common in palliative care to give estimates in term of life events that the patient may be anticipating, that is, birthday, graduation, wedding, and so on. When answering such questions, health care providers should answer questions directly and honestly, be open about areas of uncertainty, and offer answers of hope. In cases where these goals seem to conflict with each other, the artistic practitioner openly communicates accurate information while continuing to support hope within the patient or the family. It is also important to emphasize that patients can sometimes postpone death until after an important anticipated event (such as a wedding or holiday) (24).

Congestive Heart Failure

CHF is a chronic illness that is associated with severe morbidity as well as mortality. Hospital admissions for patients with heart failure have risen from 1985 to 1995 (25). As therapies allow individuals to live longer, heart failure has become an illness of the elderly. Large trials such as the Framingham Heart Study have unfortunately not shown a decrease in overall death rates (26) despite therapeutic advances. Currently, because there is no curative treatment for end-stage heart failure, treatment remains palliative in nature.

Heart failure patients often endure multiple symptoms during the course of the illness and face recurrent hospitalizations. This dramatic increase in health care utilization places physical, emotional, and financial burdens on the patients, families, and society. The number of heart failure patients that comprise the hospice population is approximately 10% according to the Standards and Accreditation Committee and Medical Guidelines Task Force (8). This relatively low rate may partly be due to the lack of recognition of end-stage CHF as a life-limiting disease.

Heart failure is a chronic disease that occurs after several different causes such as myocardial infarction, valvular disease, and arrhythmias. Several risk factors such as advanced age and uncontrolled blood pressure also add to the increased likelihood of developing CHF. Symptoms of heart failure stem from the decreasing functionality of the heart to maintain adequate perfusion to the body. Many symptoms such as breathlessness and edema are treated symptomatically with diuretics. The management of heart failure employs more preventive then curative strategies. For example, early control of blood pressure and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor treatment are important therapies that have been shown to increase survival in high-risk individuals. But once CHF progresses into the advanced stages, these preventative strategies are far less helpful; symptom management in advanced heart failure management mostly improves quality of life and functional outcomes. The clinical course of heart failure follows the classical trajectory of chronic illness. There is a gradually declining functional baseline, interrupted by points of crises, followed by aggressive revival to a new functional baseline that is typically lower than that previously experienced.

Functional indicators provide the most accurate measure of prognostication (25). Cardiopulmonary testing is the most

accurate measure of determining functional status but this may not necessarily be the most practical method in the advanced heart failure patient population. Guidelines which can be useful in guiding the health care provider in determining prognosis include the following: The Medical Guidelines for Determining Prognosis in Selected Non-Cancer Disease for Congestive Heart Failure (Table 43.4), the NYHA classification (Table 43.5) which is the most commonly used, the Minnesota living with Heart Failure questionnaire (27), and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy questionnaire (28). These guidelines complement a practitioner’s clinical judgment in determining the severity of disease.

accurate measure of determining functional status but this may not necessarily be the most practical method in the advanced heart failure patient population. Guidelines which can be useful in guiding the health care provider in determining prognosis include the following: The Medical Guidelines for Determining Prognosis in Selected Non-Cancer Disease for Congestive Heart Failure (Table 43.4), the NYHA classification (Table 43.5) which is the most commonly used, the Minnesota living with Heart Failure questionnaire (27), and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy questionnaire (28). These guidelines complement a practitioner’s clinical judgment in determining the severity of disease.

Table 43.4 Medicare Hospice Guidelines—Congestive Heart Failure | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Prognostic criteria are derived from several large heart failure trials (9, 31). Yet, the evidence for prognostication is limited from these trials because of underrepresentation of women, elderly, and nonwhite individuals, as well as the propensity for such trials to focus on less advanced CHF (32). Hospice is currently employed very late in the course of this illness. This is partly because of the inability to make an accurate prognosis (33). Medicare provides guidelines for prognosis on the basis of data from clinical heart failure trials which may help resolve some of this uncertainty. Involving palliative care early in CHF is likely to alleviate symptoms and may result in improved drug compliance, fewer hospital stays, and decreased psychosocial suffering. In fact, this may provide a transition for the patient into the hospice setting (19).

Table 43.5 New York Heart Association Functional Classification | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the causative virus of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were 40 million people living with HIV/AIDS, 3 million HIV-/AIDS-related deaths, and 5 million new infections in 2003 worldwide. AIDS therapy and research has progressed significantly since the time that HIV was first discovered. Currently, there are multiple medications and a multitude of treatment regimens. But these advances in treatment can also produce greater side effects and pain (34).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree