Iwant to die at home, Paul Newman tells his family as he’s given ‘weeks to live.’” So read the headline in the London Daily Mail newspaper in August 2008. Mr. Newman died 6 weeks later. Patients and families both dread and crave this kind of precise, accurate prognostic information as they make their plans for care at the end of life. Unfortunately, however, most clinicians have trouble estimating and talking about patient’s prognoses. Because one-third of the population now dies from cancer and close to 90% die from chronic life-limiting illnesses in which death can be anticipated, contemporary physicians need to develop their prognostic abilities.

Prognostication, along with diagnosis and therapeutics, has always been a cardinal clinical skill of physicians. In fact, in 400 BC, Hippocrates wrote a Book of Prognostics and began with the following invocation:“It appears to me a most excellent thing for physicians to cultivate Prognosis; for by foreseeing and foretelling, in the presence of the sick, the present, the past and the future and explaining the omissions which patients have been guilty of, he will be the more readily believed to be acquainted with the circumstances of the sick; so that men will have the confidence to entrust themselves to such a physician” (http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/prognost.html, translated by Francis Adams. Accessed October 7, 2011).

Until 150 years ago, prognosis was closely linked to diagnosis-because there were very few effective options for treating diseases (at least morphine was available to make the death less distressing). This all began to change in the Civil War era with the development of anesthetics and safe surgical techniques. The discovery in the early 20th century of antibiotics and other pharmacotherapy led to an uncoupling of this historic nexus between diagnosis and prognosis, with prognosis being displaced by therapeutics. Nicholas Christakis has referred to this as the “ellipsis of prognosis in modern medical thought” (

1).

It is now 40 years since President Richard Nixon signed the National Cancer Act. Although the death rates for cancer in the United States have dropped by 22% for men and 14% for women and there are more than 10 million survivors (AACR Progress Report for 2011. http://www.aacr. org/Uploads/DocumentRepository/2011CPR/2011_AACR_ CPR_Text_web.pdf. Accessed September 23,2011), the reality is that more than 570,000 people died of cancer in 2011 and it will soon become the number 1 killer of Americans. As we move into the second decade of the 21st century, predicting the survival of patients who will die from their cancer continues to be an abiding clinical competency.

The reasons why prognostication needs to be revived as a core clinical skill that is a competency of palliative and supportive care physicians are shown in

Table 45.1. Patients and families need prognostic information to make their plans, but there are many other reasons why predicting survival of patients with advanced cancer is an important clinical skill. Time-to-death is also important as a technical pre-requisite for high-quality clinical decision making such as whether to perform a surgery, place an intrathecal pump, or refer a patient to hospice. Prognostication is gaining greater legal and regulatory importance, beyond the qualification for hospice benefits. In New York State, the Palliative Care Information and Counseling Act of 2010 mandates that physicians and nurse practitioners will discuss palliative care options with all patients who have a prognosis of 6 months or less. Prognosis is also important for the design (inclusion/exclusion criteria) and analysis (stratification according to survival) of clinical trials. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, prognostic categories could also form the basis for a common language in palliative care. Oncologists have the TNM classification that allows them to distinguish between different stages of cancer independent of other factors, but palliative care physicians lack such taxonomy.

Because of the ellipsis of prognosis in modern medical thought, most physicians still do not receive any formal training in how to go about this ancient clinical skill. Therefore, it is not surprising that modern physicians avoid prognosticating and do not like doing it when they cannot avoid it. A decade ago, a random sample of internists revealed that although the typical internist not infrequently addressed the question “How long do I have to live?” withdrew or withheld life support, and referred patients to hospice, they generally disdained prognostication (

2). Some 60% found it stressful or difficult; almost half wait to be asked by a patient before offering predictions; more than three-quarters believed patients expect too much certainly; exactly half believed that if they were to make an error, patients might lose confidence; 90% believed they should avoid being too specific; and more than half reported inadequate training in prognostication. These attitudes clearly have significant consequences for patient care.

There are several other forces operating against physicians’ prognostications, in addition to not being well educated on how to do it. First, given that prognosis is concerned with what is arguably the most inherently uncertain, and often the most troubling, domain of clinical knowledge, it seems likely that physicians will continue to adopt variable, meaningful, and consequential responses to it in an effort to cope. Second, until recently survival predictions have been in the realm of subjective judgment and there has been no rational basis on which approach to it. Subjective judgments are known to be inaccurate and physicians only want to base their treatment decisions on accurate information. Third, for some physicians prognosis is not only unscientific but should not be attempted, “Only the Father knows the hour” (Mark13:32). Stories like that of Oscar the Cat, the resident feline in a Providence, RI nursing home with almost absolutely accurate prognostic skills, superior to any human being do not help in this regard, either (

3). Finally, physicians in general and oncologists in particular do not like to take away a patient’s hope (

4).

As a result of these negative attitudes toward predicting survival, several “norms” of prognostication had developed. Do not do it unless asked. Be vague. Put an optimistic spin on it. Do not discuss it with colleagues (

5). In reviving prognostication as a core clinical skill in palliative care, all of these barriers need to be removed, and a new set of attitudes developed. Fortunately, a new science of prognosis has begun to emerge in the last 10 years. Some of the important concepts are as follows.

Prognostication has two components: formulation of the prediction or “foreseeing” and communicating the prediction or “foretelling.” There is a growing body of evidence supporting both of these skills. Both are equally important because there is no point being a good communicator if the content of the message is erroneous. And there is no point formulating an accurate prognosis if the way it is delivered has an undesired effect on the patient.

Two types of judgment may be used when formulating a prognosis: subjective or actuarial. With subjective judgment, the clinician formulates the prognosis in his or her head. With actuarial judgment, the human judge is replaced by a decision based on a prognosis factor, or combination of factors, whose importance and weighting has been predetermined from data (

6). In general, actuarial judgment is preferred in medicine to subjective judgment. However, in the case of prognostication, the actuarial models we have as yet are only as good as subjective judgment. There are various advantages and disadvantages to using these two kinds of judgment for prognosis, to be discussed later.

This chapter mainly focuses on predicting survival in patients with advanced cancer. But it is important to understand that there is more to prognosis than answering the question “How long do I have?” The definition of prognosis found in clinical epidemiology textbooks is more generic. It is “the relative probabilities of the various outcomes of the natural history of a disease.” In the case of patients with advanced cancer, palliative and supportive care clinicians may be called on to predict many outcomes other than death. These could include further progression of disease; occurrence or recurrence of complications such as bowel obstruction, spinal cord compression, or hypercalcemia; structural or functional limitations due to the disease or its treatment and their impact on the activities of daily living; pain, other physical symptoms, and psychosocial distress; adverse effects of therapies; and the cost of care (see

Table 45.2). These different domains of prognostication have been labeled the “five D’s” of prognosis: Death, Disease progression, Disability, Drug toxicity, and Dollars (cost) (

7). A sixth D-“Derivative health”-could perhaps be added, representing the externalities of a disease on others. For example, morbidity and mortality are known to increase in the bereaved spouses of patients who have passed, and this effect has been shown to be ameliorated by hospice (

8).

Little information is available on the kind of rules or principles which clinicians follow or the kind of observations and interpretations they utilize when making a clinical estimate of survival in a patient with advanced cancer. Subjective judgments are widely used in general life and many important decisions depend on them. Subjective judgments should not be mistaken as necessarily haphazard guesswork if they may follow a well-defined process. For example, specified criteria can be set down for the judge of a singing contest to evaluate. These include singing ability, originality, stage presence, and

overall performance. The judgment will have more credibility if there is a scoring sheet and a panel of judges.

The factors that influence clinicians when they are formulating a prognosis have not been studied, but a prospective list is shown in

Table 45.3. Even a junior medical student can recognize a patient who is actively dying: the patient is pale, malnourished, bedridden, has poor oral intake, the vital signs are unstable, and the biochemistry is abnormal. The prognosis is then measured in hours to days. But how prognoses of so many weeks, months, or years are formulated is unclear. Recent developments in the science of prognosis can provide a framework for developing, improving, and teaching better clinical predictions of survival (CPS).

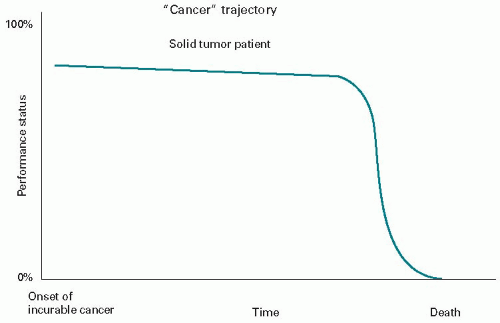

First, guidance for subjective judgment of survival comes from the so-called death trajectories of life-limiting illnesses (

Figs. 45.1 and

45.2) (

9,

10).

Figure 45.1 shows the typical death trajectory of the solid tumor patient once they have limited treatment options. There has been a long period of good function on treatment (with the assistance of a supportive or palliative care program). This is followed by a relatively short period once the cancer becomes overwhelming, of a monophasic decline with losses in function and well-being which are obvious each week. The individual’s death is relatively predictable, and referral to hospice should occur earlier than it currently does.

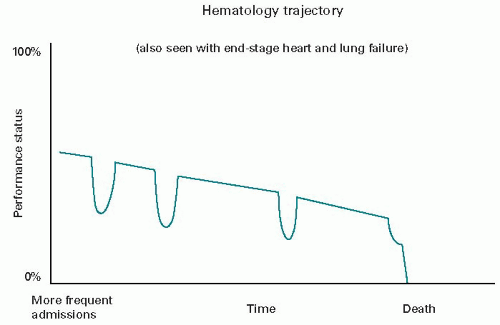

The death trajectory of hematology/oncology patients is less clear cut. It maybe more like that of the organ failure patient (

Fig. 45.2), with a more gradual decline punctuated by acute, life-threatening episodes that are potentially treatable (e.g., sepsis, respiratory failure, and bleeding). Each acute episode is met by rescue treatment and followed by nearly the prior function status. Eventually, though, one of the complications will be lethal. Since it is not possible in advance to know which one, the current hospice program

is mostly unavailable. Death in this course is usually experienced as sudden and unexpected for each patient, even though the median survival time of these diseases is well known.

Second, a conceptual framework has been proposed by Mackillop (

11) and begins with the diagnosis, which is associated with a general prognosis (e.g., 6 months for the typical Stage IV lung cancer patient). This general prognosis then needs to be individualized by adjusting for other clinical findings such as the patient’s performance status, symptoms, complications of the cancer and comorbid conditions, and psychosocial factors such as mood and social support. The relative importance of different prognostic factors varies across the course of the disease. In early-stage cancer, the prognosis is most influenced by attributes of the cancer (primary, metastases, tumor grade, and volume) and the effects of treatment. In patients with advanced disease, clinical factors’ performance status, symptoms and laboratory measures, and psychological factors (mood and social support)-referred to as “interactions between the host, tumor and treatment”-have most impact on the prognosis (

12).

Third, unlike the diagnosis and treatment, the prognosis is dynamic, especially if there is an effective treatment. Therefore, it should be reviewed and revised at clinically relevant intervals. If the lung cancer responds to therapy and shrinks, then the prognosis would need to be revised upward. If there is no response or the patient develops high-grade toxicities, then it may need to be downgraded.

Fourth, prognosis can be formulated as two different types of predictions. One is a prediction of the time-to-death (or other event), referred to as a “temporal” prediction. The other type is a prediction of the absolute risk of the death occurring, for example, percentage chance of surviving 1 month, referred to as a probabilistic prediction. The accuracy of temporal predictions is poor; the accuracy of probabilistic predictions can be quite high, and they are generally well calibrated if imprecise (

13).

SUBJECTIVE JUDGMENT OF PROGNOSIS

In modern medicine, it is preferable to use data to determine diagnosis, therapy, toxicity, or prognosis, rather than relying on the clinician’s subjective judgment. To be accurate with subjective judgment requires a lot of experience with the condition; the experience to have been broadly representative and unbiased; the possession of a good memory; the ability to be discriminate (dying or not) and well calibrated (patients with a worse prognosis die sooner); a dispassionate temperament. Valid, reliable tools for actuarial judgment of survival in advanced cancer are becoming increasingly available, reducing the need for clinical predictions, but subjective judgment still has a place. Some of the actuarial tools are hybrids that incorporate a score for the clinician’s prediction of survival; the appropriate tool is less accurate than subjective judgment; inputs for the tool are not available (e.g., recent blood work); the patient may not have a disease in which the tool was validated or the tool may need recalibration for this patient population; and the output may not be easily calculable or does not provide the type of prognostic information that is required in this clinical situation. Principles of subjection judgment of prognosis are listed in

Table 45.3.

Numerous studies over the last 40 years have shown that clinicians are not very good at subjective judgment of survival, especially when the predictions are temporal. One of the earliest studies evaluating the performance of physicians’ temporal predictions in terminally ill cancer patients was performed at St. Christopher’s Hospice, London, in 1969 to 1970 (

14). Referring physicians and the admitting physician at the hospice were asked to estimate individual patients’ prognoses in terms of weeks. These CPSs were then compared with the actual survival (AS). The median CPS was 2 months but the median AS was only 3.5 weeks. Less than 10% of CPSs were accurate. More than half were out by factor of 2 and approximately 40% were out by even more. Two-thirds of inaccurate predictions overestimated the AS. It was noteworthy that

there was no difference in accuracy between the referring physicians’ CPS and the hospice physicians’ CPS.

In a systematic review of studies, the accuracy of CPS subsequently confirmed this tendency to be overoptimistic when predicting survival in terminal cancer patients (

15). The CPS generally overestimated the survival (median CPS of 42 d vs. median AS of 29 d). CPS was correct to within 1 week in only 2 5% of cases, and overestimated AS 1 by at least 4 weeks in 27%. The longer the CPS, the greater the variability in the AS. Although agreement between CPS and AS was poor, the two were highly correlated out to 6 months. These data suggested that clinicians can discriminate but are poorly calibrated when it comes to predicting survival in terminal cancer.

Some studies included in the review also provided data on prognostic factors such as performance status, symptoms, and use of steroids. Combining these factors with the CPS improved the accuracy of the prediction, although the additional value was small. The explained variance in AS increased from 0.51 to 0.54 when these actuarial data were added.

One of the studies included in the review evaluated the reasons why CPS tends to overestimate survival (

16). Almost 350 physicians provided CPS in more than 450 patients at the time of referral to five outpatient hospice programs in Chicago. The average time on hospice was 24 days. Only 20% of the CPSs were accurate (defined here as being within 33% of the AS); two-thirds were overoptimistic. Overall, physicians overestimated survival by a factor of 5.3.

Because this study involved a large number of referring physicians, the authors were able to look at the patient and physician-related factors influencing the accuracy of CPS. The results were surprising; few patient or physician-related characteristics were associated with prognostic accuracy. In particular, patient characteristics such as age, race, diagnosis, functional status, and illness duration were not associated with prognostic error (with the exception that male patients were less likely to have overly pessimistic predictions). Several physician attributes were also generally not associated with error, including age, sex, race, specialty, and dispositional optimism, although non-oncology medical specialists were more than three times more likely to make overly pessimistic predictions than general internists. Experience did matter, with physicians in the upper quartile of practice experience being the most accurate. The length and the intensity of doctor-patient relationship were also associated with prognostic error, but the results were counterintuitive: As the duration of physician-patient relationship increased and the time since last contact decreased, prognostic accuracy decreased. The better the physician knew the patient, the more likely the error was to be overoptimistic. It could be argued based on these data that if an accurate CPS is required, an experienced specialist who does not know the patient should be called in for a “second opinion.”