Epidemiology and Prognostication in Advanced Cancer

Elizabeth B. Lamont

Nicholas A. Christakis

One meaning of prognosis is a physician’s estimate of the future course of a patient’s disease and especially of their survival. Prognoses are important to physicians and patients in all phases of cancer care, and they inform both medical and nonmedical decisions. In early-stage disease, prognoses help physicians and patients to weigh the likely benefit of given therapies (e.g., adjuvant chemotherapy). In advanced stage disease, prognoses may be of additional importance, as they may herald a switch from primarily curative or life-prolonging care to primarily palliative care and in so doing set off a cascade of both clinical and personal decisions. Despite its importance and ubiquity, reliable prognostication in advanced disease is not straightforward. Numerous studies have revealed substantial optimistic bias in physicians’ prognoses for their patients terminally ill with cancer. It seems likely that this optimistic bias may contribute to the short survival observed in patients referred for hospice care and to other types of decisions doctors and patients make near the end of life. Research that is focused on improving physicians’ prognostic abilities is therefore of critical importance to palliative care.

Prognostic Inaccuracy

Although prognosis is a central element of a significant amount of oncologic research, formal and explicit prognostication is not often required in the clinical care of patients with cancer. Nevertheless, there are two instances in the care of patients with advanced cancer where physicians are asked explicitly to prognosticate when they are enrolling patients on experimental chemotherapy protocols, and when they are referring patients for hospice care. Each therapy has discrete and opposite eligibility requirements pertaining to survival— that is, to be considered for enrollment on phase I experimental chemotherapy protocols, patients typically must have an estimated survival of longer than 3 months. To be considered for enrollment for hospice care under the Medicare Hospice Benefit, patients must have an estimated survival of less than 6 months. Because of these formal requirements, physicians’ ability to determine fine gradations in survival among patients in their last 6 months of life may mean the difference between aggressive and palliative care.

Optimism in Formulating Prognoses

How good are physicians at determining which patients are in their last 6 months of life? The answer may be found in disparate sources of literature, that is, literature pertaining to both aggressive and palliative therapies for patients with advanced cancer. From the experimental chemotherapy literature; Janisch et al. analyzed survival data from 349 patients with advanced cancer after enrollment in phase I therapies (1). Overall, they found that the median survival was 6.5 months, well above the requisite 3 months described in most eligibility requirements. However, 25% died within 3 months (i.e., inconsistent with the prognostic standard), although very few of those with a performance status of more than 70 died before 3 months. Given the low clinical response rates associated with phase I therapies, it is unlikely that survival was enhanced by the therapies themselves. Therefore, results from this study suggest that physicians enrolling patients on phase I protocols are generally able to predict which patients have longer than 3 months to live. An alternate explanation is that other eligibility requirements, such as performance status and laboratory tests, select patients with longer than 3 months to live, obviating the utility of the physicians’ prognostic assessment. Because the study was not designed to test physicians’ prognostic accuracy, it is difficult to draw strong conclusions about the actual role of physicians’ prognostication.

Within the palliative care literature, there are several studies specifically designed to determine physicians’ prognostic accuracy in predicting survival of patients admitted to hospice programs (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Investigators in these studies have measured physicians’ prognostic accuracy by comparing patients’ observed survival to their predicted survival (these predictions are not necessarily ones communicated to patients; rather, they are ones physicians formulate for themselves). Results of the studies, summarized in Table .1, show that, in aggregate, physicians’ overall survival estimates tended to be incorrect by a factor of approximately three, always in the optimistic direction.

Studies of physicians’ abilities to predict survival of patients terminally ill with cancer are not limited to patients in palliative care settings but have also been evaluated in ambulatory patients undergoing anticancer therapy. Mackillop and Quirt measured oncologists’ prognostic accuracy in the care of their

ambulatory patients with cancer by asking them to first predict patients’ likelihood of cure and then to estimate the duration of survival for those whose likelihood of cure was zero (9). At the 5-year point, patients who were alive and disease-free were termed “cured;” the dates of death of the incurable patients also were determined. The researchers reported that oncologists were highly accurate in predicting cure. That is, for subgroups of patients (not individual patients) the ratio of the observed cure rate at 5 years to the predicted cure rate was quite high, at 0.92. However, the same oncologists had difficulty predicting the length of survival of individual incurable patients. They predicted survival “correctly” for only one third of patients, with the errors divided almost equally between optimistic and pessimistic.

ambulatory patients with cancer by asking them to first predict patients’ likelihood of cure and then to estimate the duration of survival for those whose likelihood of cure was zero (9). At the 5-year point, patients who were alive and disease-free were termed “cured;” the dates of death of the incurable patients also were determined. The researchers reported that oncologists were highly accurate in predicting cure. That is, for subgroups of patients (not individual patients) the ratio of the observed cure rate at 5 years to the predicted cure rate was quite high, at 0.92. However, the same oncologists had difficulty predicting the length of survival of individual incurable patients. They predicted survival “correctly” for only one third of patients, with the errors divided almost equally between optimistic and pessimistic.

Table 42.1 Summary of Studies Comparing Physicians’ Estimated Survival to Patients’ Actual Survival | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Optimism in Communicating Prognoses

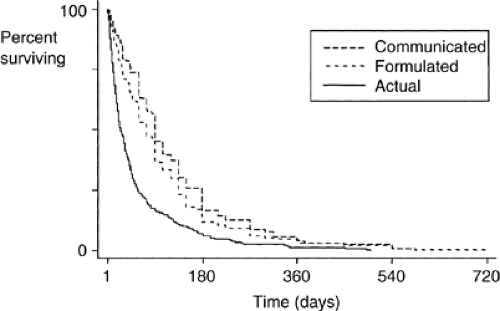

Once a prognosis has been formulated, a physician must decide how to communicate it. This is the distinction between foreseeing and foretelling the patient’s future (10). Although, as noted in the preceding text, there is unconscious optimism in the prognoses physicians formulate regarding the survival of their patients’ with advanced cancer, there is also additional— and conscious— optimism in the prognoses physicians subsequently communicate to their patients. For example, one study asked physicians referring patients terminally ill with cancer for hospice care, how long they thought the patient had to live and also what prognosis, if any, they would provide to their patient if the patient inquired (11). It found that the median survival the physicians would communicate to patients was 90 days, their median formulated survival was 75 days, and the median observed survival was 24 days. This study revealed that the prognoses patients hear from their physicians may be more optimistic than what their physicians actually believe, which again is more optimistic than what actually occurs. Figure 42.1 shows the relationship between these three types of prognoses (communicated, formulated, and observed).

In sum, although physicians are asked to foresee gradations of survival in patients with advanced cancer enrolling in certain therapies (either aggressive or palliative), they are able to do so accurately less than a third of the time and, when in error, they generally tend to overestimate survival. This overestimation in formulated survival is compounded by an overestimation of communicated survival. Therefore, through their physicians’ stepwise prognostic errors, patients with advanced-stage cancer may become twice removed from the reality of their survival, both times toward a falsely optimistic prognosis.

Prognostic Accuracy

Within palliative care, there is a growing literature focused on identifying predictors of survival of patients with advanced cancer that might aid physicians in their prognostic estimates for similar patients. This literature is motivated not only by the centrality of prognosis to the care of such patients but also by physicians’ inability to prognosticate accurately and their discomfort in doing so. Multiple prospective and retrospective cohort studies have consistently identified three broad classes of survival predictors: patients’ performance status, patients’ clinical signs and symptoms, and physicians’ clinical predictions. New research seeks to increase the predictive yield of these clinical factors through models of increasing complexity that integrate these elements with each other and with new elements into easy-to-use composite measures. Additional new research in the broader oncologic arena of translational research seeks to exploit survival aspects of new biological markers [i.e., molecular (e.g., BCR-ABL

rearrangement in chronic myelogenous leukemia (12), EGFR mutations in non– small cell lung cancer (13)].

rearrangement in chronic myelogenous leukemia (12), EGFR mutations in non– small cell lung cancer (13)].

Table 42.2 Karnofsky Performance Status Scale | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Performance Status

A performance status is a global measure of a patient’s functional capacity. Because it has been consistently found to predict survival in patients with cancer, it is frequently used as a selection criteria for patients entering clinical trials and also as an adjustment factor in the subsequent analyses of treatment effect 14. Several different metrics have been developed to quantify performance status, and among them, the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) is the most often used. The KPS ranges from values of 100, signifying normal functional status with no complaints or evidence of disease, to zero, signifying death. The complete spectrum of values for the KPS scale is reproduced in Table 42.2.

Multiple studies have reported associations between survival of patients’ with cancer and their performance status (1, 3, 6, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28). The direction of the association is positive— that is, as a patient’s performance status declines, so, too, does their survival. The magnitude of the association is described differently in different studies depending on the statistical methods used, but several studies report that among patients enrolled in palliative care programs, a KPS of less than 50% suggests a life expectancy of fewer than 8 weeks (3, 6, 15, 17, 28, 29). The association between KPS value and survival in patients with advanced cancer enrolled in palliative care programs is described in Table 42.3.

Table 42.3 Predictors of Survival With Advanced Cancer Under Palliative Care | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree