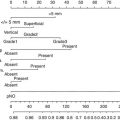

Region

Number of cases

Age-standardized incidence (per 100,000)

Africa

Algeria, Setif

0

–

Tunisia, Centre, Sousse

0

–

Zimbabwe, Harare: African

19

0.9

Uganda, Kyadondo County

25

2.8

America, Central and South

Chile, Valdivia

6

0.7

France, La Martinique

9

0.7

Brazil, Brasilia

80

3.7

America, North

Canada, Northwest Territories

0

–

USA, California, Los Angeles County: Filipino

0

–

USA, California, Los Angeles County: Japanese

0

–

USA, California, Los Angeles County: Korean

0

–

Canada, Prince Edward Island

1

0.2

USA, California, Greater San Francisco Bay Area: Chinese

3

0.2

USA, Ohio: Black

8

0.2

USA, New Mexico: non-Hispanic White

10

0.2

USA, New Mexico: American Indian

7

1.8

Asia

Israel

19

0.1

Thailand, Songkhla

58

2.2

Europe

Italy, Brescia Province

4

0.2

Spain, Murcia

57

1.4

Oceania

USA: Hawaii: Chinese

0

–

USA: Hawaii: Hawaiian

0

–

USA: Hawaii: Japanese

3

0.2

Australia, Northern Territory

4

1.1

Hernandez and colleagues assessed incidence and mortality in 4,967 American men diagnosed with histologically confirmed invasive penile SCC between 1998 and 2003 using population-based data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program for Cancer Registries, and the National Center for Health Statistics [9]. Overall, median age at presentation was 68 years old. A steady increase of the average, age-adjusted annual incidence of penile SCC, from 13.8 % in patients younger than 50 years to 26.4 % in patients 70–79 years old, was observed during the study period. Despite an overall incidence of less than 1 % (ASR = 0.81), Hispanic ethnicity and residence in Southern regions and in areas of the United States with low socioeconomic status correlated with considerable disparities in invasive penile cancer incidence. In fact, excess incidence of invasive penile cancer was 72 % higher in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics, comparable between White and Black men, and approximately twofold lower in Asians/Pacific Islanders. Lower rates of circumcised Mexican Americans compared to non-Hispanic Whites were considered as one of the reasons for excess risk of penile SCC among Hispanics. Risk factors for excess mortality included residence in the Southern and in regions of the United States with low socioeconomic status in addition to the Black race. Of note, certain histologic and anatomic site differences related to race and ethnicity were observed.

Using the SEER database, Rippentrop and coworkers analyzed the associations between different demographic variables and the prevalence, presentation, and survival of patients with penile SCC in the US population [13]. No difference in the incidence of penile cancer in the African-American and White men was noted. However, time to death in patients with regional disease and relative risk (RR) of death from penile cancer in the African-American and White population was significantly different despite similar overall cancer prevalence in the two groups. In the authors’ opinion, the presence of an underlying pathologic difference between the two racial categories or the impact of lower socioeconomic factors and decreased access to health care contributed to a delay in diagnosis that resulted in higher disease stages at presentation in African-Americans. The overall worse prognosis for African-Americans compared with Whites appeared to be related to (a) more aggressive disease, (b) more advanced disease due to decreased access to health care or a delay in seeking medical attention, and (c) less frequently performed or reported lymphadenectomy in the Black population.

The improvement in hygienic standards and socioeconomic status in recent years has possibly led to some decline in incidence in many countries including the United States [10, 14–18], where approximately 1,570 new cases of penile cancers were diagnosed and 310 cancer-related deaths were projected, respectively, in 2012 [19]. Other studies have shown a stable incidence of invasive penile cancer [20]. Although Pukkala and Weiderpass did not find an impact of social class variation on the incidence of penile cancer in Finland [21], Colon-Lopez et al. showed that socioeconomic factors continue to hold an impact on incidence and mortality in developing countries [22]. Analyzing the Puerto Rico Cancer Registry and the US SEER database, Puerto Rican men were found to have an approximately threefold higher incidence of penile cancer as compared to non-Hispanic White Americans (standardized rate ratio [SRR]: 3.33; 95 % confidence interval [CI]: 2.80, 3.95) and non-Hispanic Black Americans (SRR: 3.04; 95 % CI: 2.21, 4.36). The incidence of penile cancer in Puerto Rican men was also more than two times higher than that US Hispanic men (SRR: 2.59; 95 % CI: 1.99, 3.43). In a similar fashion, the cancer-specific mortality in Puerto Rican men was higher than in all other ethnic/racial groups included in the study. Furthermore, Puerto Rican men in the lowest socioeconomic position index had 70 % higher incidence of penile cancer as compared with those PR men in the highest socioeconomic position index (SRR: 1.70; 95 % CI: 0.97, 2.87). However, only the low educational component of the socioeconomic position was significantly (p < 0.05) associated with higher penile cancer incidence (SRR: 2.18; 95 % CI: 1.42, 3.29).

Although most of the reported studies found a declining incidence of penile cancer in recent years, a few studies reported an increasing incidence of carcinoma in situ (CIS), high-grade PIN, and penile cancer [20, 23]. In the Netherlands, the overall age-standardized incidence of penile SCC increased from 1.4 to 1.5 per 100,000 person-years with an average annual percentage change (AAPC) of 1.3 % (95 % CI: 0.1 %, 2.6 %). This appeared to be the result of earlier diagnosis and therefore increased incidence rate of penile CIS from 0.1 to 0.3 with an AAPC of 4.5 % (95 % CI: 2.0 %, 6.9 %) [20]. In Denmark, the overall age-standardized incidence rate of penile cancer increased from 1.0 to 1.3 per 100,000 men-years in 1978–1979 to 2006–2008, representing an AAPC of 0.8 % (95 % CI: 0.17 %, 0.37 %). In the same study, the incidence of PIN increased significantly in 1998–1999 to 2006–2008 with an AAPC of 7.1 % (95 % CI: 3.3 %, 11.1 %) [23]. In the authors’ opinion, the high prevalence of HPV and the low circumcision rates in Denmark partly explained the results of their study.

Number of sexual partners, marital status, and cohabitation seem to correlate with the risk of developing penile cancer. Rippentrop et al. showed that married patients sought care earlier than unmarried patients, thus presenting with disease at a lower stage (CIS or localized disease) and having a significantly stage-by-stage longer time to cancer death. Married patients were also more likely to pursue more aggressive treatment of their condition. On multivariated analysis, however, no difference in prevalence or RR of death was noted in married or unmarried individuals [13]. Ulff-Moller et al. examined the incidence trends of invasive penile SCC and the impact of marital and cohabitation status on the risk of developing the disease [24]. A total of 1,292 cases of invasive penile SCC in Denmark during 65.6 million person-years between 1978 and 2010 were studied. The average incidence rate (1.05 cases per 100,000 person-years) and the world age-standardized incidence rate (p-trend = 0.41) remained stable during the studied period. The risk of developing invasive penile SCC in single-living and unmarried Danish men increased with the number of prior cohabitations. Unmarried (hazard ratio [HR] 1.37; 95 % CI: 1.13, 1.66), divorced (HR 1.49; 95 % CI: 1.24, 1.79), or widowed (HR 1.36; 95 % CI: 1.13, 1.63) patients were at increased risk of invasive penile SCC when compared to married men. Single-living men were at increased risk of invasive penile SCC compared to men in opposite-sex cohabitation (HR 1.43; 95 % CI: 1.26, 1.62). Risk increased with increasing numbers of prior opposite-sex (p-trend = 0.02) and same-sex (p-trend < 0.001) cohabitations. Greater exposure to HPV secondary to less stable sexual relations might explain the findings in the study subgroups.

Etiology

The etiology of penile cancer is multifactorial [12, 25, 26]. In a review of scientific publications on penile cancers between 1996 and 2000, phimosis (inability to fully retract the foreskin), chronic inflammatory conditions (i.e., balanoposthitis, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus), and treatment with psoralen and ultraviolet A photochemotherapy (PUVA) were identified as strong risk factors associated with an odds ratio (OR) greater than 10 [25]. Other risk factors, such as poor hygiene, history of smoking, multiple sexual partners, and history of genital warts, have been identified.

Phimosis is present in up to one half of patients with penile cancer. Although preventive circumcision has been suggested in patients with phimosis living in areas with high incidence of penile cancer [27], adult circumcision failed to show a protective effect since men never circumcised or circumcised after the neonatal period had, respectively, a 3.2 and 3.0 times higher risk compared to men circumcised as neonates [26]. In a population-based case–control study conducted in western Washington State between 1979 and 1998, men not circumcised during childhood resulted at increased risk of invasive (OR = 2.3; 95 % CI: 1.3, 4.1) but not in situ (OR = 1.1; 95 % CI: 0.6, 1.8) penile cancer [28]. Approximately 35 % of men with penile cancer who had not been circumcised in childhood and 7.6 % of controls reported a history of phimosis (OR = 7.4; 95 % CI: 3.7, 15.0). Phimosis was found to be strongly associated with development of invasive penile cancer (OR = 11.4; 95 % CI: 5.0, 25.9) in men not circumcised in childhood. The risk of invasive penile cancer in men with no phimosis and not having been circumcised in childhood was not elevated (OR = 0.5; 95 % CI: 0.1, 2.5). On the contrary, neonatal circumcision is associated with a threefold decreased risk of invasive penile cancer since it protects against phimosis, poor penile hygiene, and retention of desquamated epidermal cells and urinary products resulting in chronic inflammation of the glans and prepuce. Nonetheless, 20 % of penile cancer patients had been circumcised neonatally [25, 28]. Interestingly, Schoen and colleagues determined that the level of protective effect of neonatal circumcision for CIS is not as high as that for invasive penile cancer [29]. Of 89 men with invasive penile cancer whose circumcision status was known, 2 (2.3 %) had been circumcised as newborns and 87 (97.7 %) were not circumcised. Of 118 men with CIS whose circumcision status was known, 16 (15.7 %) had been circumcised as newborns.

Lichen sclerosus (LS), an unusual chronic mucocutaneous condition of the penis preferentially involving the foreskin but also the glans, coronal sulcus, and urethra, was found to cause phimosis and to be associated with the usual, verrucous, papillary, and pseudohyperplastic subtypes of invasive penile carcinoma in 30–50 % of patients [12, 30]. In a retrospective study from Italy, Nasca and colleagues reported penile invasive SCC or premalignant lesions in 9 of 86 men (9.3 %) with a history of penile LS after a mean lag time of 18 (range, 10–34) years. The transition from LS to frank neoplastic foci was histologically evident in all cases of SCC [31]. Powell and coworkers retrospectively found histological or clinical evidence of LS in 11 of 20 patients with SCC of the penis [32]. SCC was well differentiated in seven of the eight cases with histologic evidence of LS in the excision specimen. Only 3 SCCs were well differentiated among the 12 cases with no evidence of LS, although a history of LS sometimes preceding the SCC by 10 years was identified in the records of 7 of these 12 patients. Of the ten deceased patients in this study, seven died from metastatic disease. The authors concluded that the association between SCC of the penis and LS was present even in the patients in whom the clinical presentation of LS or the need for circumcision preceded the SCC by many years. A large retrospective study from Paraguay assessed the anatomic distribution and prevalence of LS in patients with SCC of the penis [30]. The penectomy and circumcision specimens from 207 patients with carcinoma and giant condylomas were examined, and 68 (33 %) patients were found with evidence of LS; however, the true association was felt to be likely underestimated. The preferential anatomic site of LS was the foreskin, although involvement was noted at the level of the glans and coronal sulcus, including the urethra. The gross and microscopic findings suggested that LS may represent preneoplastic condition for at least some types of penile cancers, in particular those not related to HPV. Evidence of LS was found in 28 % of 155 patients with penile carcinoma studied prospectively by Pietrzak and colleagues [33]. Prowse et al. investigated the role of HPV infection and expression of the tumor suppressor protein p16INK4A in the pathogenesis of penile cancer [34]. In 26 penile SCCs and 20 independent penile LS, HPV DNA was found in 54 % of penile SCCs and 33 % of penile LS patients. Strong immunostaining for p16INK4A correlated with HPV 16/18 infection in both penile LS and penile SCC. Penile SCC margins were also associated with penile LS in 13 of 26 lesions. HPV was detected in 7 of the 13 SCC cases associated with LS and in 6 of the 11 SCC lesions not involving LS. Barbagli and coworkers evaluated the presence of premalignant or malignant lesions in 130 patients with LS involving the male genitalia. Eleven (8.4 %) men with genital LS showed premalignant or malignant histopathological features including 7 (64 %) with SCC. Based on all these studies, it has been estimated that the risk of malignant transformation of penile LS is similar to vulval lichen sclerosus (4–8 %) [35].

Stern reported on the risk of genital tumors in 892 patient with psoriasis treated with oral methoxsalen (8-methoxypsoralen) and PUVA [36]. In his 12.3-year prospective study, 30 genital neoplasms in 14 (1.6 %) patients were identified between 1976 and 1989. Compared to expected morbidity (based on population incidence data), patients treated with PUVA had a standard morbidity ratio of 95.7 (95 % CI: 43.8, 181.8) for invasive SCC of the penis and scrotum and 58.8 (95 % CI: 26.9, 111.7) for invasive and in situ penile tumors. When compared to the general population or patients exposed to low levels of PUVA, the incidence of invasive SCC in patients exposed to high levels of PUVA was 286 times and 16.3 times higher, respectively (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). After controlling for the level of exposure to PUVA, patients exposed to high levels of ultraviolet B radiation were found to have a risk of genital tumors 4.6 times higher than that in other patients (95 % CI: 1.4, 15.1). Considering the strong dose-dependent increase in the risk of genital tumors associated with exposure to PUVA and ultraviolet B radiation, the author recommended the use of genital protection (e.g., shielding) in men exposed to PUVA or other forms of ultraviolet radiation. In a subsequent update of this experience nearly 10 years later, the development of genital cancer in ten new cohort patients confirmed the persistence of the risk associated with PUVA exposure despite the increased use of genital protection and the decreased use or the discontinuation of PUVA. Men previously unaffected by such tumors developed cancer in the decade starting nearly 15 years after initial exposure to PUVA, with an overall risk of invasive scrotal and penile SCC since enrollment 81.7 times (95 % CI: 52.1, 122.6) higher than that expected in the general population. Multivariate analyses revealed the highest genital tumor risk among men with high-dose exposure to both PUVA and topical tar/ultraviolet B, with an incidence rate ratio of 4.5 (95 % CI: 1.3, 16.1) compared with the low-dose exposure group. Another study by Perkins et al. showed a greater than 300-fold increase in genital tumors in 130 patients with psoriasis treated with PUVA [37].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree