PG, a 15-year-old boy, presented to the paediatric endocrine clinic with delayed puberty and complaining of thirst and polyuria. Investigations revealed hypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus caused by a craniopharyngioma, a cystic tumour of the hypothalamus. He was treated with surgery and radiotherapy. Postoperatively he had deficiencies of all the anterior pituitary hormones requiring hormone replacement and persistent diabetes insipidus treated with DDAVP (see Chapter 35 ). In the year following treatment he gained 22 kg in weight. He found it extremely diffi cult to control his food intake and his mother noticed he would continue to eat any food that was in front of him. Attempts to follow a calorie-restricted diet failed.

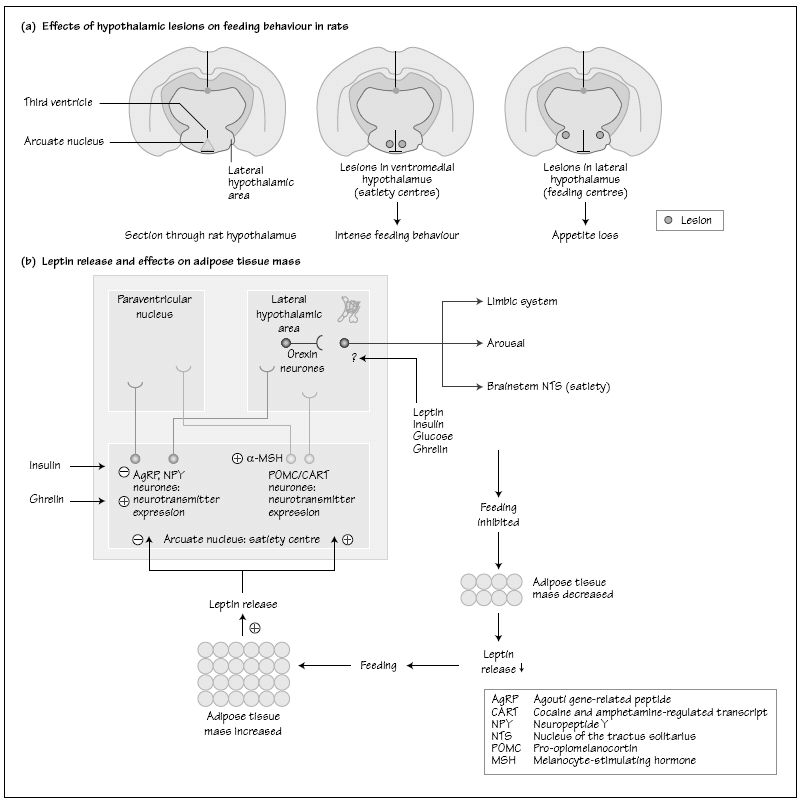

Energy homeostasis is controlled by the integration of autonomic input and peripheral signals by the brain. Hypothalamic regions involved in this process have been identified in experimental systems, predominantly involving two neuronal populations, the orexigenic neuropeptide Y/Agouti-related peptide neurones and the anorexic pro-opiomelanocortin/ cocaine and amphetamine-related transcript (CART) system. These are interconnected and affected by a number of hormones including insulin, glucocorticoids and leptin. It is likely that the hypothalamic obesity syndrome seen in patients with diseases of the hypothalamus and suprasellar regions relates to disruption of these homeostatic mechanisms.

Several lines of evidence point to an important neural role in the control of energy homeostasis, whose status depends mainly on the synchronization of food intake, energy utilization and energy storage. This synchronization appears to be effected largely by the autonomic and neuroendocrine systems. Lesions in the lateral hypothalamus block feeding behaviour in rats to the point of starvation, while lesions in the ventromedial area cause voracious feeding and massively obese rats (Fig. 45a

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree