Fig. 15.1

EOC grade 1

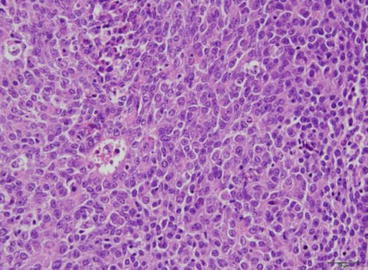

Fig. 15.2

EOC grade 3

Adequate sampling of the tumors should enable to establish whether EOC arises in endometriosis, adenofibromatous endometrioid precursors, or de novo. It should allow correct grading and evaluation of tumor extension for staging and give information about presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion.

Differential Diagnosis

Low-grade tumors (grades 1 and 2) display a variety of histological patterns such as squamous differentiation with morules (30–50 %); clear-cell changes; mucinous glands; sex cord-like, mucin rich, ciliated cell features; oxyphilic changes and secretory changes; and spindle cell patterns with hyalinization and even heterologous elements. Unusual appearances can cause major problems in differential diagnosis. The most common of such variants are EOC with sex cord-like patterns that can be confused with sex cord-stromal tumors like adult granulosa cell tumors or sertoli cell tumors. Immunohistochemistry of inhibin and EMA is helpful in this setting, as EC is inhibin negative and EMA positive, whereas granulosa and sertoli cell tumors are EMA negative and inhibin positive [25, 26].

Clear-cell change in secretory EOC or EOC with squamous differentiation may be confused with clear-cell carcinoma. Recently, a panel of immunohistochemical markers containing HNF1β, napsin A, ER, and PR showed a very good specificity of napsin A in differentiating EC from CCC. In addition, ER and PR are diffusely and strongly expressed in EC, but absent or only focally positive in CCC [25, 27, 28].

EOC with spindle cell features, hyalinization, and corded aspects with heterologous elements may be confused with carcinosarcoma. In contrast to spindle cell EOC, heterologous sarcomatous components of carcinosarcoma have high-grade cytological features, and the border between carcinomatous and sarcomatous components is clear-cut showing no merging of epithelial and spindle cell areas as encountered in spindle cell EOC.

Endometrioid yolk sac tumors (YSTs) may be distinguished from endometrioid carcinoma by the absence of EMA and cytokeratin 7 expression. On the other hand, YSTs express SALL4, a marker of germ cell neoplasia, negative in EOC.

Papillary low-grade endometrioid carcinomas may challenge differential diagnosis with serous carcinoma. In this setting, the morphological clue to diagnosis is the discordance between architectural and cytological features.

Among high-grade tumors, grade 3 EOC may be confused with serous carcinoma with a prominent glandular pattern. Immunohistochemistry is helpful as serous carcinomas most often harbor p53 mutations, show diffuse and intense p16 and nuclear WT1 expression, and are vimentine negatives. However, as some grade 3 EOC may be p53 mutated (11–33 %), overlapping features can render distinction of the two types difficult [28]. Some of the high-grade endometrioid carcinomas represent probably glandular forms of serous carcinoma [29, 30]. As serous carcinomas behave more aggressively than grade 3 EOC, immunohistochemistry should be employed in order to correctly classify the tumor [31] – see Table 15.1.

EOC should further be distinguished from metastasis of extraovarian adenocarcinomas as colorectal adenocarcinoma (cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 positive and cytokeratin 7 negative) or endocervical adenocarcinoma (mostly showing diffuse expression of p16 and negative staining for vimentine, RE, RP, as well as positive cytoplasmic staining for CEA).

In cases of concomitant uterine and ovarian EC, a low-grade uterine EC with minimal or no myometrial invasion favors two independent primaries [33].

Prognosis of Endometrioid Ovarian Carcinoma

Given the differences in carcinogenesis, supporting that type I and II carcinomas are separate entities, plus the fact that most endometrioid carcinomas of the ovary belong to the type I class, one may speculate that patient outcomes are different as well. In an analysis of 929 patients (270 with pure endometrioid carcinoma and 659 with high-grade serous tumors), Storey et al. showed that endometrioid carcinoma patients did better in terms of progression-free and overall survival [4]. Not surprisingly, although the majority of patients had high-grade tumors, less patients harbored this subtype in the endometrioid carcinoma group, and more endometrioid carcinoma patients were at earlier FIGO stages. The authors reported that more endometrioid patients were “debulked” to less than 2 cm residual lesions, but fewer had chemotherapy. Despite the limitations of this study, the median progression-free survival favored the endometrioid patients (24 vs. 13 months, p < 0.001). However, when the authors compared the outcomes of the subgroup stage III/“optimally” debulked, the difference was not significant (21 vs. 16 months, p = 0.219), however favoring endometrioid patients. Overall survival again favored the endometrioid carcinoma patients (48 vs. 22 months, p < 0.001) and remained significantly better in stage II and III patients (81 vs. 46 months, p = 0.0219, and 33 vs. 22 months, p = 0.002, respectively). This difference in overall survival was also found in another study, despite having as well the disadvantages of being retrospective and having recruited patients over decades [34]. Conversely, in a small study recruiting 42 patients, no survival difference was found [35]. Wang et al. investigated patients’ outcome according to the presence of concomitant endometriosis. Not surprisingly, those patients were younger and had earlier FIGO stage and more low-grade tumors. The presence of concomitant endometriosis was linked to a better survival in univariate, but not multivariate analysis [36].

Interestingly, response to platinum-based chemotherapy was similar in both groups in the study by Storey et al. that is consistent with the fact that most patients had high-grade tumors that are more likely to be chemosensitive than low-grade tumors [4].

Treatment

The treatment guidelines for ovarian cancer (irrespectively to pathologic subtypes) include several cornerstones, among which are adequate staging, carcinologic surgery, and chemotherapy [37]. Among the past years, a number of phase III trials have established the standards of medical care for advanced ovarian cancer, again, not specifically focusing on a particular subtype, excepted perhaps for clear-cell carcinoma. Platinum-based combination with paclitaxel combined with bevacizumab in advanced ovarian cancers is considered as the frontline treatment standard and applies to all epithelial ovarian cancer subtypes. Of note, the recent phase III trials focusing onto advanced ovarian cancer have enrolled an overwhelming majority of high-grade serous tumors, as compared to endometrioid carcinomas. For example, the GOG 218 trial that investigated upfront/maintenance bevacizumab recruited a mean of 84 % of high-grade serous tumors versus 3 % of endometrioid carcinomas [38]. In the ICON-7 trial that also investigated bevacizumab, 69 % of enrolled patient had serous carcinoma, but the number of endometrioid carcinoma patients enrolled was not reported [39]. It is therefore extremely difficult (and probably impossible) to speculate on potential differences of treatment efficacy that may arise from pathologic subtypes.

Future Directions

As in a number of other malignancies such as lung, breast, colorectal cancer, and others, recent advances have focused on the dismemberment of cancers according to their molecular profile. More than providing evidences regarding carcinogenesis, this effort undoubtedly drives advances in tumor management especially toward the identification of “druggable” targets. Of note, a recent translational study in endometrial cancer (the TransPORTEC-3 initiative) identified four different prognosis groups according to molecular profiles that are (in part) close to those encountered in ovarian endometrioid cancer [40]. However, low-grade endometrioid carcinomas of the endometrium and the ovary do have distinct molecular profiles as PTEN mutations are far more frequent in endometrial tumors (67 vs. 17 %, p < 0.0001), whereas CTNNB1 mutations are in turn more frequent in ovarian tumors (57 vs. 28 %, p < 0.0057), possibly due to distinct microenvironments [32, 41]. These data reinforce the need for designing innovative translational approaches to ovarian cancer, particularly at the scale of cooperative groups (such as the GINEGEPS within the French GINECO group).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree